Added and Omitted Plates in the Book of Urizen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John W. Ehrstine, William Blake's Poetical Sketches

REVIEW John W. Ehrstine, William Blake’s Poetical Sketches Michael J. Tolley Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 2, Issue 3, December 15, 1968, pp. 55-57 -55- ; ' •.' • -.' ; : >• '■ * ■ REVIEW ' --; ■- - '■ :<x .■■•■■ ■ \,' oz Bweoq n#t Wi 11iam Blake's Poetical Sketches, by John W. Ehrstine. Washington State University Press (1967), pp. DO + 108 pp. '■■■><' It is a pity that the first fulllength study of the Poetical Sketched to be published since Margaret Ruth Lowery's pioneering work of 1940 should be so little worthy the serious attention of a Blake student. Ehrstine is one of the familiar new breed of academic bookproducers, whose business is not scholarship but novel thesisweaving* Having assimilated certain ideas and critical tech niques, they apply them ruthlessly to any work that has hithertobeen fortunate enough to escape such attentions. The process is simple and: the result—that of bookproduction—is infallible. If the poor little poems protest while struggling in their Procrustean bed, one covers their noise with bland asser' 1" tions and continues to mutilate them. Eventually they satisfy one's preconcep" tions. Unfortunately, they may also impose on other people. In revewing such books one must blame mainly the publishers and their advisors; secondly the universities for their incredibly lax assessment and training of postgraduate students; thirdly the authors, who are usually dupes of their own'1 processes, for rushing into print without consult!ng the best scholars In their field. Ehrstine shows his lack of scholarship on the first two pages of his book; thereafter he has an uphill tattle!1n convincing the reader that he has some special insights Which compensate foKtfris, once fashionable, disability. -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

The Symbol of Christ in the Poetry of William Blake

The symbol of Christ in the poetry of William Blake Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nemanic, Gerald, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 18:11:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317898 THE SYMBOL OF CHRIST IN THE POETRY OF WILLIAM BLAKE Gerald Carl Neman!e A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the 3 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the. Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL. BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: TABLE OF COITENTS INTRODUCTION. -

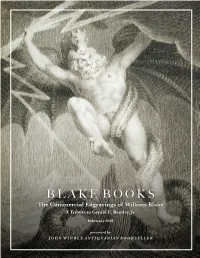

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

The Prophetic Books of William Blake : Milton

W. BLAKE'S MILTON TED I3Y A. G.B.RUSSELL and E.R.D. MACLAGAN J MILTON UNIFORM WirH THIS BOOK The Prophetic Books of W. Blake JERUSALEM Edited by E. R. D. Maclagan and A. G. B. Russell 6s. net : THE PROPHETIC BOOKS OF WILLIAM BLAKE MILTON Edited by E. R. D. MACLAGAN and A. G. B. RUSSELL LONDON A. H. BULLEN 47, GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1907 CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. INTRODUCTION. WHEN, in a letter to his friend George Cumberland, written just a year before his departure to Felpham, Blake lightly mentions that he had passed " nearly twenty years in ups and downs " since his first embarkation upon " the ocean of business," he is simply referring to the anxiety with which he had been continually harassed in regard to the means of life. He gives no hint of the terrible mental conflict with which his life was at that time darkened. It was more actually then a question of the exist- ence of his body than of the state of his soul. It is not until several years later that he permits us to realize the full significance of this sombre period in the process of his spiritual development. The new burst of intelle6tual vision, accompanying his visit to the Truchsessian Pi6lure Gallery in 1804, when all the joy and enthusiasm which had inspired the creations of his youth once more returned to him, gave him courage for the first time to face the past and to refledl upon the course of his deadly struggle with " that spe6lrous fiend " who had formerly waged war upon his imagination. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 23

Ryan Postgraduate English: Issue 23 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 23 September 2011 Editors: Naomi Marklew and Jack Baker ‘Mental Things are alone Real’: The Building of the Labyrinth - William Blake’s Analysis of the Psyche. Mark Ryan * * University of Nottingham ISSN 1756-9761 1 Ryan Postgraduate English: Issue 23 ‘Mental Things are alone Real’: The Building of the Labyrinth - William Blake’s Analysis of the Psyche. Mark Ryan University of Nottingham Postgraduate English, Issue 23, September 2011 This paper will investigate the conceptual influence of three mystical thinkers, Jacob Boehme, Paracelsus and to a lesser extent, Emmanuel Swedenborg upon the works of William Blake and specifically explains the common themes they share with regards to an understanding of psychic growth and disturbance. The reason that this is important is that critics supporting the psychoanalytical thesis have tended to impose their ideas on the works of Blake, without considering theories of the mind that predated and informed Blake’s psychological system. As the article will demonstrate there are other Blake scholars who have investigated, for example, Blake’s apparent echoing of vocabulary from the writings of the mystic philosophers and the themes of social conflict and ideas pertaining to Creation, Fall and Redemption found in Boehme. However, there has not been a full investigation of Blake’s appropriation of Paracelsus’ and Boehme’s ideas with application to his investigation of human psychology. It should -

William Blake and His Poem “London”

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1610-1614, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1610-1614 William Blake and His Poem “London” Changjuan Zhan School of Foreign Languages, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, China Abstract—This paper gives a detailed introduction to William Blake, a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher; and the most original romantic poet as well as painter and printmaker of the 18th century. Then his works are also introduced according to time order among which two of his collections of poems, i.e. “the songs of innocence” and “the songs of experiences” are given special attention. The features and comments on his works are introduced and demonstrated in his most famous poem “London”, from “the songs of experiences”. The paper analyzes the various technical features in this poem respectively—key image and three encounters around which the whole poem is centered; symbolism and capitalization which are used a lot in it; the choice and repetition of words which enhance the theme of the poem; and the rhyme and rhythm which give the poem a musical pattern. And then a conclusion is made that through these features, William Blake did achieve an overall impact which convey the horror and injustice that was London. Index Terms—William Blake, London, technical features, image, capitalization, repetition, rhyme and rhythm I. AN INTRODUCTION TO WILLIAM BLAKE A. William Blake’s Life William Blake was a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher. -

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake Author(s): PAUL MINER Source: Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Winter 1962), pp. 59-73 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23091046 Accessed: 20-06-2016 19:39 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 19:39:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAUL MINER* r" The TygerGenesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake There is the Cave, the Rock, the Tree, the Lake of Udan Adan, The Forest and the Marsh and the Pits of bitumen deadly, The Rocks of solid fire, the Ice valleys, the Plains Of burning sand, the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire, The Islands of the fiery Lakes, the Trees of Malice, Revenge And black Anxiety, and the Cities of the Salamandrine men, (But whatever is visible to the Generated Man Is a Creation of mercy & love from the Satanic Void). (Jerusalem) One of the great poetic structures of the eighteenth century is William Blake's "The Tyger," a profound experiment in form and idea. -

William Blake the Book of Urizen London, Ca

® about this book O William Blake The Book of Urizen London, ca. 1818 ➤ Commentary by Nicolas Barker ➤ Binding & Collation ➤ Provenance ©2001 Octavo. All rights reserved. The Book of Urizen Commentary by Nicolas Barker The Book of Urizen, originally entitled The First Book of Urizen, occupies a central place in William Blake’s creation of his “illuminated books,” both chronologically and in the thematic and structural development of the texts. They are not “illuminated” in the sense that medieval manuscripts are illu- minated—that is, with pictures or decoration added to an exist- ing text. In Blake’s books, text and decoration were conceived together and the printing process, making and printing the plates, did not separate them, although he might vary the colors from copy to copy, adding supplemen- tary coloring as well. Like the books themselves, the technique for making them came to Blake by inspiration, connected with his much-loved younger brother Robert, whose early death in 1787 deeply distressed William, though his “visionary eyes beheld the released spirit ascend heaven- ward through the matter-of-fact Plate 26 of The Book of Urizen, copy G (ca. 1818). ceiling, ‘clapping its hands for joy.’” The process was described by his fellow- engraver John Thomas Smith, who had known Robert as a boy: After deeply perplexing himself as to the mode of accomplishing the publication of his illustrated songs, without their being subject to the expense of letter-press, his brother Robert stood before him in one of his visionary imaginations, and so decidedly directed him in the way in which he ought to proceed, that he immediately fol- lowed his advice, by writing his poetry, and drawing his marginal subjects of embellishments in outline upon the copperplate with an impervious liquid, and then eating the plain parts or lights away William Blake The Book of Urizen London, ca. -

William Blake

THE WORKS of WILLIAM BLAKE jSptfrolu, tmir dpritical KDITEO WITH LITHOORAPIIS OF THE ILLUSTRATED “ PROPHETIC BOOKS," AND A M8 M0 IH AND INTERPRETATION EDWIN JOHN ELLIS A ttlh n r n f “Miff »ii A rcatliit,** rfr* Asn WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS Author of ** The JVnnilerinfj* nf Ohin,** " The Crwutesi Kathleen," ifr. “ Hnng nin to the te»t Ami I Lh* m&ttor will iv-wnnl, which nmdnp** Would ftumlml from M Jfauttef /.V TUJIKE VOI.S. VOL 1 LONDON BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY 1893 \ A lt R ig h t* k *M*rv*ifl & 0 WILLIAM LINNELL THIS WORK IS INSCRIBED. PREFACE. The reader must not expect to find in this account of Blake's myth, or this explanation of his symbolic writings, a substitute for Blake's own works. A paraphrase is given of most of the more difficult poems, but no single thread of interpretation can fully guide the explorer through the intricate paths of a symbolism where most of the figures of speech have a two-fold meaning, and some are employed systematically in a three fold, or even a four-fold sense. " Allegory addressed to the intellectual powers while it is altogether hidden from the corporeal understanding is my definition," writes Blake, "of the most sublime poetry." Letter to Butts from Felpham, July 6th, 1803. Such allegory fills the "Prophetic Books," yet it is not so hiddon from the corporeal understanding as its author supposed. An explanation, continuous throughout, if not complete for side issues, may be obtained from the enigma itself by the aid of ordinary industry. -

Dissertations on William Blake

ARTICLE “The Eternal Wheels of Intellect”: Dissertations on William Blake G. E. Bentley, Jr. Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 224-243 224 "THE ETERNAL WHEELS OF INTELLECT": DISSERTATIONS ON WILLIAM BLAKE G. E. BENTLEY. JR. illiam Blake has been the subject of doctoral seems likely that there were more dissertations on Wdissertations for over sixty years, and a Blake written in Germany and Japan than are recorded sufficient number have been completed and here. accepted—over two hundred—to make it possible to draw some interesting conclusions about patterns of The national distribution of the universities interest in William Blake and about patterns in higher at which the degrees were awarded is striking: education. In general, the conclusions which these Canada 14 (mostly from Toronto), England 24 (mostly facts make possible, at least to me, confirm what Oxford, Cambridge, and London), Finland 1, France 3 one might have guessed but supply the facts to Germany 4, India 3, Ireland 1, Japan 2, New Zealand' justify one's guesses. 1, Scotland 1, Switzerland 4, the United States 204. I have no record of Blake doctoral dissertations Before one places much weight upon either the in Australia, Italy, or South Africa. About 96% facts or the conclusions based upon them, however, are from the English-speaking world,14 which is not one must recognize the fragmentary nature of our surprising, and about 77% are from the United States evidence and whence it comes. About 60% of those which I suppose is not really surprising either, theses of which I have records are listed in considering that there must be about as many Ph.D. -

![Printed Performance and Reading the Book[S] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8900/printed-performance-and-reading-the-book-s-of-urizen-blakes-bookmaking-process-and-the-transformation-of-late-eighteenth-century-print-culture-2988900.webp)

Printed Performance and Reading the Book[S] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture

Colby Quarterly Volume 35 Issue 2 June Article 3 June 1999 Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture John H. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 35, no.2, June 1999, p. 73-89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Jones: Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bo Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation ofLate Eighteenth Century Print Culture by JOHN H. JONES NTIL RECENTLY, CRITICS have considered the textual problems in The U [First] Book of Urizen as impediments in their search for a definitive, synoptic edition of the poem. While eight copies of the poem are known to exist, each copy is unique for a variety of reasons, including missing plates, changes in plate order, inconsistencies with chapter and verse numbering, and individual plate alterations. About these difficulties Jerome McGann notes that no editors have been willing to pursue their quest for narrative consistency far enough so as to remove one or another of the duplicate chapters 4. Furthermore, all later editions enshrine the problem of this unstable text in that curious title-so difficult to read aloud-with the bracketed word: The [First] Book of Urizen.... Thus a residue of the text's "extraordinary inconsistency" always remains a dra matic presence in our received scholarly editions.