Nigerian Veterinary Journal 38(3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

LIST July 29 – August 7, 2016

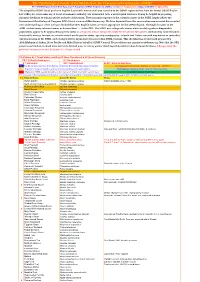

Sunrise Birding LLC www.sunrisebirding.com UGANDA Leader: Julian Hough & local guides SPECIES LIST July 29 – August 7, 2016 BIRDS Scientific Name 1 White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 2 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 3 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 4 African Black Duck Anas sparsa 5 Yellow-billed Duck Anas undulata 6 Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 7 Crested Guineafowl Guttera pucherani 8 Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 9 Handsome Francolin Pternistis nobilis 10 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 11 Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 12 Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 13 African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 14 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 15 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 16 African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 17 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia hagedash 18 White-backed Night Heron Gorsachius leuconotus 19 Striated Heron Butorides striata 20 Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides 21 Rufous-bellied Heron Ardeola rufiventris 22 Western Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 23 Gray Heron Ardea cinerea 24 Black-headed Heron Ardea melanocephala 25 Purple Heron Ardea purpurea 26 Great Egret Ardea alba 27 Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia 28 Little Egret Egretta garzetta 29 Hamerkop Scopus umbretta 30 Shoebill Balaeniceps rex 31 Pink-backed Pelican Pelecanus rufescens 32 Reed Cormorant Microcarbo africanus 33 White-breasted Cormorant Phalacrocorax lucidus 34 Black-winged Kite Elanus caeruleus 35 African Harrier-Hawk Polyboroides typus 36 Palm-nut Vulture Gypohierax angolensis 37 Hooded Vulture -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Trichomonas Galllinae Infection in European Turtle Doves Streptopelia Turtur in Africa and Potential for Transmission Among Co-Occurring African Columbiformes

A report from a BOU-funded Project Jenny Dunn et al Trichomonas galllinae infection in European Turtle Doves Streptopelia turtur in Africa and potential for transmission among co-occurring African columbiformes Trichomonas galllinae infection in European Turtle Doves Streptopelia turtur in Africa and potential for transmission among co-occurring African columbiformes JENNY C. DUNN1, REBECCA C. THOMAS2, DANAË K. SHEEHAN1, ALY ISSA3 & OUMAR ISSA3 1 RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, RSPB, The Lodge, Potton Road, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, UK. 2 School of Biology, Irene Manton Building, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK. 3 Fondation NATURAMA, Secteur 30, 01 BP 6133, Ouagadougou 01,Burkina Faso. BACKGROUND Trichomonas gallinae is an emerging avian pathogen in the UK and across Europe, leading to population declines in songbirds (especially greenfinches Carduelis chloris) where prevalence is high (Robinson et al., 2010). The parasite is present worldwide, and elsewhere it is typically a pathogen of columbiformes, where it can have population limiting effects (Bunbury et al., 2008). Recent work has shown a high prevalence in UK columbiformes, with the highest rates of infection (86%) in the migratory European Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur (Lennon et al., 2013). Infected individuals do not necessarily exhibit clinical signs, and carriers without clinical signs may transfer disease organisms between sites during migration (e.g. Rappole et al., 2000) and exhibit reduced survival (Bunbury et al., 2008). European Turtle Doves breeding in the UK are thought to have a non-breeding range spanning much of the Sahel in West Africa, coinciding with the range of several species of Afro-tropical columbids. -

Ec) No 1332/2005

19.8.2005 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 215/1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) NO 1332/2005 of 9 August 2005 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, of Namibia and South Africa), Euphorbia spp., Orchidaceae, Cistanche deserticola and Taxus wallichiana were amended. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, (5) The species Malayemis subtrijuga, Notochelys platynota, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of Amyda cartilaginea, Carettochelys insculpta, Chelodina 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna mccordi, Uroplatus spp., Carcharodon carcharias (currently and flora by regulating trade therein (1), and in particular listed on Appendix III), Cheilinus undulatus, Lithophaga Article 19(3), thereof, lithophaga, Hoodia spp., Taxus chinensis, T. cuspidata, T. fuana, T. sumatrana), Aquilaria spp. (except for A. malaccensis, which was already listed in Appendix II), Whereas: Gyrinops spp. and Gonystylus spp. (previously listed in Appendix III) were included in Appendix II to the Convention. (1) At the 13th session of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, hereinafter ‘the Convention’, held in Bangkok (Thailand) in October (6) The species Agapornis roseicollis was deleted from 2004, certain amendments were made to the Appendices Appendix II to the Convention. to the Convention. (2) The species Orcaella brevirostris, Cacatua sulphurea, Ama- zona finschi, Pyxis arachnoides and Chrysalidocarpus decipiens (7) Subsequent to the thirteenth session of the Conference of were transfered from Appendix II to the Convention to the Parties to the Convention, the Chinese populations of Appendix I thereto. -

Phthiraptera: Amblycera, Ischnocera) from 7 Egyptian Pigeons and Doves (Columbiformes), with Description of One New Species

$FWD7URSLFD ² Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Acta Tropica journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actatropica New records of chewing lice (Phthiraptera: Amblycera, Ischnocera) from 7 Egyptian pigeons and doves (Columbiformes), with description of one new species Eslam Adlya,⁎, Mohamed Nassera, Doaa Solimana, Daniel R. Gustafssonb, Magdi Shehataa a Department of Entomology, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt b Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resources, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Conservation and Utilization, Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Little information is available about the chewing lice of wild birds of Egypt, including common groups such as Egypt pigeons and doves (Columbiformes). Through this work, parasitic chewing lice of common columbiformes of New species Egypt were revised including new data. Three species of pigeons and doves (Streptopelia decaocto Frivaldszky New records 1838, Spilopelia senegalensis Linnaeus 1766 and Columba livia Gmelin 1789) were examined for chewing lice at Chewing lice three different localities. A total of 124 specimens of lice were collected. Nine species were identified from these Columbiformes samples; one species (Columbicola joudiae n. sp.) was considered a new species to science, six species were Columbicola fi fi Coloceras recorded from Egypt for the rst time, and two species have been identi ed in Egypt before. Taxonomic and fi Campanulotes ecological remarks for all identi ed chewing lice samples are provided along with known and local hosts, Colpocephalum measurements and material examined. Description and images of the new species are also provided. 1. Introduction the Rock Dove is the most widely domesticated by humans for hundreds of years and have become feral in cities around the world (Beletsky, The study of chewing lice has been neglected for many years in the 2007). -

Abundance and Diversity of Birds in the Ogbese Forest

1 Original Research Article 2 3 ABUNDANCE AND DIVERSITY OF 4 BIRDS IN THE OGBESE FOREST 5 RESERVE, EKITI STATE, NIGERIA 6 7 8 9 Abstract 10 A study was carried out to evaluate the species composition and relative abundance of bird 11 species of the natural and plantation forest of Ogbese Forest Rserve, Ekiti State .The study 12 was conducted from April, 2010 to February, 2011 covering both wet and dry seasons. 13 Sample sites were stratified based on the vegetation types and transect count techniques was 14 employed for the evaluation. A total of 52 bird species consisting of 47 resident and 5 15 immigrant species was recorded. The species composition of birds during the wet and dry 16 seasons was not significantly different. The natural forest vegetation had the highest species 17 diversity and evenness. The relative abundance score of species during the Wet and dry 18 seasons was variable in both habitats. The result of this study has shown that the natural and 19 plantation vegetation types of Ogbese Forest Reserve, Ekiti State. The heterogeneity of flora 20 species in the natural forest compared to the plantation forest might be responsible for the 21 variation. The management of birds in the reserve should take cognizance of the vegetation 22 types for effective conservation of bird species which are resident in the reserve. 23 24 Key words: Vegetation, Diversity, Abundance, Immigrants, Birds 25 Introduction 26 Avifauna is a general name for bird species. Birds are feathered, winged, egg–laying 27 vertebrates. They belong to the Kingdom “Animalia,” Phylum Chordata and class Aves. -

Performance of Sweet Pepper Under Protective

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENT Volume-3, Issue-2, Mar-May 2014 ISSN 2091-2854 Received:13 March Revised:12 April Accepted:31 May BREEDING BIOLOGY OF DOMESTICATED EURASIAN COLLARED DOVE (COLUMBIDAE) STREPTOPELIA DECAOCTO FRIVALDSZKY 1838 IN SAIDPUR, BANGLADESH M AshrafulKabir Cantonment Public School and College, Saidpur Cantonment 5311, District- Nilphamari, Bangladesh Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Two pairs of domesticated Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto reared at eighteen months for its breeding performance in intensive system. One pair was homozygous albino al//al x al//al and another pair was one wild type +//al and another albino al//al. Another experimented four pairs of doves were produced from these two pairs. Out of six pairs total 114 squabs were produced during the research period. Total three albino pairs produced 100% albino squab and different coloured male and female produced different colours which were 50% each. Sex ratio of male and female were observed 1:1. Experimental doves were reared in cages measures 23x20x16 and 25x22x18 inches and feed were supplied all day long with wheat, corn, mustard, broken rice and burnt soil. Intake feed were 15 gram per dove in a day. During the time of this observation only hypervitaminosis and worm infestations were observed and the mortality rate was few. Only in one pair (rosy ♂ x wild type ♀) produced 11 male (46%) and 13 female (54%) out of 24 squabs; this was slightly exceptional. In total 114 squabs from six pairs only one rosy male and pied rosy female were found. Breeding record of this research suggests that the colour patterns are first wild type then rosy and finally albino gradually. -

Ethiopia Endemics Birding III 11Th to 29Th November 2016 (19 Days) Trip Report

Ethiopia Endemics Birding III 11th to 29th November 2016 (19 days) Trip Report Geladas by Heinz Ortmann Trip report compiled by Tour Leaders: David Erterius and Heinz Ortmann Rockjumper Birding Tours www.rockjumperbirding.com Trip Report – RBL Ethiopia Endemics Birding III 2016 2 Tour Summary This fantastic tour through some of the more iconic and ‘birdy’ sites of Ethiopia began straight off the end of a successful and memorable extension to the Omo Valley. Having returned to the capital city, and our now familiar hotel, we headed out early on the first morning to Lake Cheleleka. This body of freshwater, although heavily impacted by urbanisation and increasingly reduced in surface area by agriculture, is a phenomenal birding spot, with several sought-after birds possible. Our morning began by ‘picking up’ some of the more common and widespread species in the agricultural fields Wattled Ibis by David Hoddinott adjacent to the lake, which included Speckled Pigeon, the seemingly ubiquitous Swainson’s Sparrow, African Sacred, Wattled and Hadada Ibises, mixed flocks of Red-billed Quelea, Northern Red Bishop and Vitelline Masked Weavers and several doves, including Dusky Turtle, Mourning Collared, Red-eyed, Laughing and Namaqua, all in good numbers. An area of moist grassland with some smaller pools of water held Spur-winged and Egyptian Goose, Yellow-billed Duck, Red-billed Teal, several Knob-billed Ducks, Red-knobbed Coot, and Abdim’s and Marabou Storks; whilst overhead we saw a lovely Greater Spotted Eagle and watched a female Western Marsh Harrier quartering slowly and low over the open grassland in search of a meal. -

FIELD GUIDES BIRDING TOURS ETHIOPIA (Incl. Rock Churches At

Field Guides Tour Report ETHIOPIA (incl. Rock Churches at Lalibela extension) May 5, 2012 to May 28, 2012 Terry Stevenson & Richard Webster Spot-breasted Lapwing is a lovely plover of high-elevation grasslands, one that has presumably declined greatly in the face of agriculture. It is still reasonably common on the Sanetti Plateau, where we look for Ethiopian Wolf. (Photo by guide Richard Webster) Success can be defined in many ways, and by most ways our journey around Ethiopia was a success. It was a birding tour, and we had great success finding Ethiopia's special birds, including some with small populations and very limited ranges. The subtitle to this birding tour also mentioned a certain Wolf, and we were very successful in seeing not only Ethiopian Wolf, but several other endemic mammals. The tour was also a logistical success: the group's curiosity about seeing much of the diversity of Ethiopia, including regions well off the tourist track, was also satisfied thanks to the behind-the-scenes work of Experience Ethiopia Tours and the on-the-scenes management of Kibrom. May is in advance of the main rainy season in Ethiopia, and this year was no exception in the north, which was brown, locally tinged green. Some rain may reach southern Ethiopia in April and May, and this year was an exception in that major rain had fallen in the southern third of the country, as it had in neighboring Kenya. Fortunately we happened to avoid coinciding with the heaviest downpours, and were able to get everywhere and enjoy an extraordinarily green landscape, and many singing and breeding species (although in a few cases, some birds may have dispersed, e.g., from Sof Omar). -

Olume 34 • No 2 • 2012

DUTCH BIRDINGVOLUME 34 • NO 2 • 2012 Dutch Birding Dutch Birding HOO F D R EDACTEU R Arnoud van den Berg (023-5378024, [email protected]) ADJUNCT HOO F D R EDACTEU R Enno Ebels (030-2961335, [email protected]) UITVOE R END R EDACTEU R André van Loon (020-6997585, [email protected]) FOTOG R A F ISCH R EDACTEU R René Pop (0222-316801, [email protected]) REDACTIE R AAD Peter Adriaens, Sander Bot, Ferdy Hieselaar, Gert Ottens, Roy Slaterus, Roland van der Vliet en Rik Winters REDACTIE -ADVIES R AAD Peter Barthel, Mark Constantine, Andrea Corso, Dick Forsman, Ricard Gutiérrez, Killian Mullarney, Klaus Malling Olsen, Magnus Robb, Hadoram Shirihai en Lars Internationaal tijdschrift over Svensson Palearctische vogels REDACTIEMEDEWE R KE R S Max Berlijn, Harvey van Diek, Nils van Duivendijk, Steve Geelhoed, Marcel Haas, Jan van der Laan, Hans van der Meulen, Kees Roselaar, Vincent van der Spek, Jan Hein van Steenis, Pieter van Veelen en Peter de Vries REDACTIE PR ODUCTIE EN LAY -OUT André van Loon en René Pop Dutch Birding ADVE R TENTIES Debby Doodeman, p/a Dutch Birding, Postbus 75611, 1070 AP Amsterdam Duinlustparkweg 98A [email protected] 2082 EG Santpoort-Zuid Nederland ABONNEMENTEN De abonnementsprijs voor 2012 bedraagt: EUR 39.50 (Nederland en België), [email protected] EUR 40.00 (rest van Europa) en EUR 43.00 (landen buiten Europa). Abonnees in Nederland ontvangen ook het dvd-jaaroverzicht. FOTO R EDACTIE U kunt zich abonneren door het overmaken van de abonnementsprijs op girorekening 01 50 697 (Nederland), girorekening 000 1592468 19 (België) of bankrekening Dutch Birding 54 93 30 348 van ABN•AMRO (Castricum), ovv ‘abonnement Dutch Birding’. -

EORC Report 2011 Final

Second report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee – 2011 Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee: Frédéric Jiguet (chairman), Mindy Baha el Din, Sherif Baha el Din, Richard Bonser, Pierre-André Crochet, Andrew Grieve, Richard Hoath, Tomas Haraldsson, Ahmed Riad & Mary Megalli (secretary) Citation: Jiguet, F., Baha el Din, M., Baha el Din, S., Bonser, R., Crochet, P.-A., Grieve, A., Hoath, R., Haraldsson, T., Riad, A., Megalli, M. 2012. Second report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee – 2011. The Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee (EORC) was launched in January 2010, to become the adjudicator of rare bird records for Egypt and to maintain the species list of birds recorded in Egypt. In 2011, the EORC was composed, as in 2010, of 9 voting members plus a non-voting secretary. Voting members were: Mindy Baha El Din, Sherif Baha El Din, Richard Bonser, Pierre-André Crochet, Andrew Grieve, Tomas Haraldsson, Richard Hoath, Frédéric Jiguet and Ahmed Riad. Mary Megalli acted as the committee secretary. In 2012, two members – Tomas Haraldsson and Ahmed Riad - tendered their resignation from the committee due to other ongoing commitments; we thank them for their involvement in the EORC. Three new members have recently been integrated into the EORC to complete the committee: Andre Corso (Italy), Manuel Schweizer (Switzerland) and Web Abdo (Egypt). Detailed information on the committee composition is available on the EORC website. Furthermore, after two years of dedicated services as a secretary, Mary Megalli becomes an external advisor to the committee, while the former chairman, Frédéric Jiguet, will now undertake the role of secretary, as a non-voting member.