Cliff-Nesting Adaptations of the Galapagos Swallow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

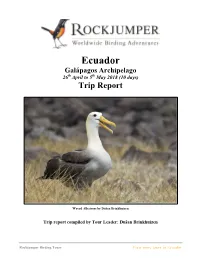

Ecuador Galápagos Archipelago 26Th April to 5Th May 2018 (10 Days) Trip Report

Ecuador Galápagos Archipelago 26th April to 5th May 2018 (10 days) Trip Report Waved Albatross by Dušan Brinkhuizen Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Dušan Brinkhuizen Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to Ecuador Trip Report – RBL Ecuador - Galápagos Archipelago 2018 2 Tour Summary Rockjumper’s amazing Galápagos adventure started at the airport of San Cristobál – the easternmost island of the archipelago. Our first bird of the trip was a stunning Mangrove Warbler hopping in the arrivals hall! Mangrove Warbler is a split from American Yellow Warbler and the distinct race aureola is only found in the Galápagos and Cocos Island. Some people saw the first Darwin’s finches from the bus during a short drive to our hotel in town. After a delicious lunch in a restaurant (lots of fresh fish available on the islands!), we started our afternoon excursion to the highlands of San Cristobál. The walk up to El Junco lagoon was scenic. We got close encounters with Grey Warbler-Finch of the San Cristobál race and also identified our first Small and Medium Ground Finches. We got to the lake just before a thick ocean mist came in. The crater lake was formed by the collapsed caldera of a volcano and is the only freshwater site on the island. It’s a great place to watch Magnificent Frigatebirds come to drink in an almost surreal setting. It was Steve that picked out a female Great Frigatebird – a scarcer species here – that we identified by the red eye-ring. White- Grey Warbler-Finch by Dušan cheeked Pintails with ducklings were present on the lake, as Brinkhuizen well as a few Common Gallinules. -

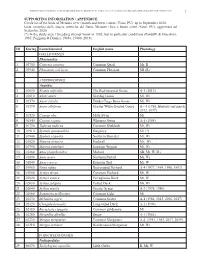

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

160-165 OB Vol 25 #3 Dec2007.Pdf

160 BOOK REVIEWS Gulls of the with sections on taxonomy, field identi - Americas . 2007. fication, individual variation, geographi - Steve N .G. Howell and cal var ia tion, hybridization, topography, Jon Dunn . Houghton molts and plumages, age terminology, Mifflin. Boston and New York. Hardcover, molt strategies and behaviour. The final 17 x 2 6 cm, 1,160 200 plus pages are Species Accounts in colour photographs, ascending order of body size. There is a 516 pages. $45.95 section on Hybrid Gulls that discusses CAN. ISBN 13:978-0- 618-72641-7. regular hybrids occurring on both coasts, almost exclusively involving large gulls. Gulls of the Americas (hereafter H & D) is The book concludes with a Glossary, the latest in the Houghton Mifflin extensive Bibliography and a section on nature guide series. It is more precisely Geographic Terms. Medium-sized pho - termed one of the Peterson Reference tographs begin species account group - Guides. Indeed, the book’s large size and ings. A range map is found on the first weight preclude it as a field guide. Steve page of each Species Account. Included Howell and Jon Dunn have produced an are an identification summary, discus - exhaustive reference work for the 36 sions on taxonomy, status and distribu - species of gulls recorded in the Americas. tion, field identification vis-à-vis similar This includes 22 species that have bred species, detailed descriptions and molt. in North America, 10 that breed in Hybrids involving other species are listed South America, and 4 that strayed from and references for further information Europe and Asia. -

The Mallophaga of New England Birds James Edward Keirans Jr

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1966 THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS JAMES EDWARD KEIRANS JR. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation KEIRANS, JAMES EDWARD JR., "THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS" (1966). Doctoral Dissertations. 834. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/834 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67—163 KEIRANS, Jr., James Edward, 1935— THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS. University of New Hampshire, Ph.D., 1966 E n tom ology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS BY JAMES E.° KEIRANS, -TK - A. B,, Boston University, i960 A. M., Boston University, 19^3 A THESIS Submitted to The University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School Department of Zoology June, 1966 This thesis has been examined and approved. May 12i 1966 Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my thanks to Dr. James G. Conklin, Chairman, Department of Entomology and chairman of my doctoral committee, for his guidance during the course of these studies and for permission to use the facilities of the Entomology Department. My grateful thanks go to Dr. Robert L. -

The Possible Significance of Large Eyes in the Red-Legged Kittiwake

192 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS that Snow Buntingsmigrating through coastalareas in LDVENSKIOLD, H. L. 1964. Avifauna Svalbardensis. the subarcticwhere spring melt has occurred are not Norsk Polarinstitutt, Oslo. only granivores, but also herbivores. MATTSON,W. J. 1980. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1:119- I thank Fred Cooke for permission to use the Snow 61. Bunting data from the La P&rouseBay Bird List (1980 MILLER, P. C., P. J. WEBBER,W. C. OECHEL,AND L. to 1984), and for commenting on the manuscript. I L. TIESZEN. 1980. Biophysicalprocesses and pri- also wish to thank Euan Dunn, Peter Ewins, Bob Jef- mary production, pp. 66-101. In J. Brown, P. C. feries, and Peter Kotanen for providing valuable com- Miller, L. L. Tieszen, and F. L. Bunnel [eds.], An ments, and Thomas Custer who reviewed the manu- arctic ecosystem: the coastal tundra ai Barrow, script. This work was carried out while the author was Alaska. U.S. IBP Svnth. Ser. 12. Dowden. Hutch- supported by a Natural Sciencesand EngineeringRe- inson and Ross, Pi. searchCouncil of Canada PostgraduateScholarship. NETHERSOLE-THOMPSON,D. 1966. The Snow Bunt- LITERATURE CITED ina. Oliver and Bovd. Edinburgh. PARMELEE,D. F. 1968: The Snow-Bunting,p. 1652- BAZELY,D. R. 1984. Responsesof salt marsh vege- 1675. In 0. L. Austin [ed.], Life historiesof North tation to grazingby LesserSnow Geese. M.Sc.thesis, American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, To- Univ. of Toronto, Canada. whees,Finches, Sparrows and allies.U.S. Nat. Mus. CARGILL,S. M., AND R. L. JEFFERIES.1984. The ef- Bull. 237. fects of grazingby LesserSnow Geeseon the vege- POLUNIN,N. -

Observations on the Breeding and Distribution of Lava Gull Leucophaeus Fuliginosus K

Cotinga 37 Observations on the breeding and distribution of Lava Gull Leucophaeus fuliginosus K. Thalia Grant, Olivia H. Estes and Gregory B. Estes Received 7 January 2014; final revision accepted 3 December 2014 Cotinga 37 (2015): OL 22–37 published online 10 March 2015 La Gaviota de Lava Leucophaeus fuliginosus, endémica del archipiélago de Galápagos, es la gaviota más rara del mundo, cuyos hábitos de reproducción son poco conocidos. En los años 2011 y 2012 se observó anidación en la isla Genovesa en densidades mayores a las reportadas previamente en Galápagos. Las parejas reproductoras fueron muy territoriales, defendiendo áreas de hasta 70 m de diámetro contra coespecíficos. Las hembras fueron más agresivas que los machos frente a los intrusos de otras especias percibidos como una amenaza. La nidada de 1–2 huevos fue incubada por ambos miembros de la pareja en turnos de dos horas. Los polluelos salieron del nido 4–5 días después de la eclosión, seleccionando lugares en el territorio más protegidos a los cuales retornaron regularmente para descansar. Los adultos reproductores fueron depredadores oportunistas, alimentando a sus crías principalmente con huevos y polluelos de aves marinas y peces robados de las mismas aves. Reconocemos una relación parasítica entre la cleptoparásita Fragata Real Fregata magnificens y la Gaviota de Lava, y sospechamos que este es el medio principal por el cual en esta isla las gaviotas adquieren los peces que comen. Presentamos datos sobre las comunicaciones entre los padres y la cría, proporcionamos la primera serie de fotografías del desarrollo del polluelo de Gaviota de Lava y describimos una característica en el plumaje de los adultos que no ha sido descrita previamente. -

Foraging Strategies of the Black-Legged Kittiwake Rissa Tridactyla at a North Sea Colony: Evidence for a Maximum Foraging Range

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 245: 239–247, 2002 Published December 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Foraging strategies of the black-legged kittiwake Rissa tridactyla at a North Sea colony: evidence for a maximum foraging range F. Daunt1, S. Benvenuti2, M. P. Harris1, L. Dall’Antonia3, D. A. Elston4, S. Wanless1,* 1NERC Centre for Hydrology and Ecology, Banchory Research Station, Hill of Brathens, Banchory AB31 4BW, United Kingdom 2Dipartimento di Etologia, Ecologia ed Evoluzione, Università di Pisa, Via Volta 6, 56126 Pisa, Italy 3Consiglia Nazional delle Ricerche, Istituto di Elaborazione dell’Informazione, Via Santa Maria 46, 56100 Pisa, Italy 4BioSS, Environmental Modelling Unit, Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen AB15 8QH, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: Black-legged kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla on the Isle of May, southeast Scotland, feed predominantly on the lesser sandeel Ammodytes marinus, an abundant, pelagic fish that is currently the subject of the largest fishery in the North Sea. The population of black-legged kittiwakes on the Isle of May is declining, and the fishery has been implicated. In order to assess this concern, there is an urgent need to improve our understanding of the factors that affect black-legged kittiwake forag- ing behaviour. During 1999, we carried out a detailed study of the foraging strategies of black-legged kittiwakes using purpose-built activity loggers that allowed us to distinguish 4 key behaviours: travelling flight, foraging flight, presence on the sea surface and attendance at the nest. We used the data to model 2 key aspects of time allocation at sea: (1) the relationship between the travelling time and trip duration and (2) the ratio of time spent actively foraging to time of inactivity on the sea sur- face at the foraging grounds. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Knutie Et Al. 2016

Knutie et al. 1 2 3 4 Galápagos mockingbirds tolerate introduced parasites 5 that affect Darwin’s finches 6 7 Sarah A. Knutie1,4*, Jeb P. Owen2, Sabrina M. McNew1, Andrew W. Bartlow1, 8 Elena Arriero3, Jordan M. Herman1, Emily DiBlasi1, Michael Thompson1, 9 Jennifer A.H. Koop1,5, and Dale H. Clayton1 10 11 12 13 Affiliations: 14 1Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA. 15 2Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA. 16 3Department of Zoology and Physical Anthropology, Complutense University of Madrid, E- 17 28040 Madrid, Spain. 18 4Current address: Department of Integrative Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 19 33620, USA. 20 5Current address: University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, Biology Department, Dartmouth, MA 21 02747, USA. 22 23 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Knutie et al. 24 Abstract. Introduced parasites threaten native host species that lack effective defenses. Such 25 parasites increase the risk of extinction, particularly in small host populations, like those on 26 islands. If some host species are tolerant to introduced parasites, this could amplify the risk of 27 the parasite to vulnerable host species. Recently, the introduced parasitic nest fly Philornis 28 downsi has been implicated in the decline of Darwin’s finch populations in the Galápagos Islands. 29 In some years, 100% of finch nests fail due to P. downsi; however, other common host species 30 nesting near Darwin’s finches, such as the endemic Galápagos mockingbird (Mimus parvulus), 31 appear to be less affected by P. downsi. 32 We compared effects of P. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

An Inter-Island Comparison of Darwin's Finches Reveals the Impact Of

RESEARCH ARTICLE An inter-island comparison of Darwin's finches reveals the impact of habitat, host phylogeny, and island on the gut microbiome 1 2 3,4 1 Wesley T. Loo , Rachael Y. Dudaniec , Sonia KleindorferID *, Colleen M. Cavanaugh * 1 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America, 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 3 College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, 4 Konrad Lorenz Research Center for Behaviour and Cognition and Department of Behavioural Biology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] (SK); [email protected] (CC) a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Darwin's finch species in the Galapagos Archipelago are an iconic adaptive radiation that offer a natural experiment to test for the various factors that influence gut microbiome com- OPEN ACCESS position. The island of Floreana has the longest history of human settlement within the archi- pelago and offers an opportunity to compare island and habitat effects on Darwin's finch Citation: Loo WT, Dudaniec RY, Kleindorfer S, Cavanaugh CM (2019) An inter-island comparison microbiomes. In this study, we compare gut microbiomes in Darwin's finch species on Flor- of Darwin's finches reveals the impact of habitat, eana Island to test for effects of host phylogeny, habitat (lowlands, highlands), and island host phylogeny, and island on the gut microbiome. (Floreana, Santa Cruz). We used 16S rRNA Illumina sequencing of fecal samples to assess PLoS ONE 14(12): e0226432. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0226432 the gut microbiome composition of Darwin's finches, complemented by analyses of stable isotope values and foraging data to provide ecological context to the patterns observed.