The Possible Significance of Large Eyes in the Red-Legged Kittiwake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

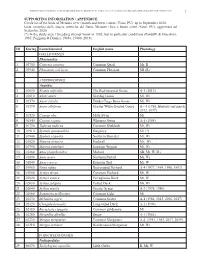

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

The Mallophaga of New England Birds James Edward Keirans Jr

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1966 THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS JAMES EDWARD KEIRANS JR. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation KEIRANS, JAMES EDWARD JR., "THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS" (1966). Doctoral Dissertations. 834. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/834 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67—163 KEIRANS, Jr., James Edward, 1935— THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS. University of New Hampshire, Ph.D., 1966 E n tom ology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE MALLOPHAGA OF NEW ENGLAND BIRDS BY JAMES E.° KEIRANS, -TK - A. B,, Boston University, i960 A. M., Boston University, 19^3 A THESIS Submitted to The University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School Department of Zoology June, 1966 This thesis has been examined and approved. May 12i 1966 Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my thanks to Dr. James G. Conklin, Chairman, Department of Entomology and chairman of my doctoral committee, for his guidance during the course of these studies and for permission to use the facilities of the Entomology Department. My grateful thanks go to Dr. Robert L. -

Foraging Strategies of the Black-Legged Kittiwake Rissa Tridactyla at a North Sea Colony: Evidence for a Maximum Foraging Range

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 245: 239–247, 2002 Published December 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Foraging strategies of the black-legged kittiwake Rissa tridactyla at a North Sea colony: evidence for a maximum foraging range F. Daunt1, S. Benvenuti2, M. P. Harris1, L. Dall’Antonia3, D. A. Elston4, S. Wanless1,* 1NERC Centre for Hydrology and Ecology, Banchory Research Station, Hill of Brathens, Banchory AB31 4BW, United Kingdom 2Dipartimento di Etologia, Ecologia ed Evoluzione, Università di Pisa, Via Volta 6, 56126 Pisa, Italy 3Consiglia Nazional delle Ricerche, Istituto di Elaborazione dell’Informazione, Via Santa Maria 46, 56100 Pisa, Italy 4BioSS, Environmental Modelling Unit, Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen AB15 8QH, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: Black-legged kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla on the Isle of May, southeast Scotland, feed predominantly on the lesser sandeel Ammodytes marinus, an abundant, pelagic fish that is currently the subject of the largest fishery in the North Sea. The population of black-legged kittiwakes on the Isle of May is declining, and the fishery has been implicated. In order to assess this concern, there is an urgent need to improve our understanding of the factors that affect black-legged kittiwake forag- ing behaviour. During 1999, we carried out a detailed study of the foraging strategies of black-legged kittiwakes using purpose-built activity loggers that allowed us to distinguish 4 key behaviours: travelling flight, foraging flight, presence on the sea surface and attendance at the nest. We used the data to model 2 key aspects of time allocation at sea: (1) the relationship between the travelling time and trip duration and (2) the ratio of time spent actively foraging to time of inactivity on the sea sur- face at the foraging grounds. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Knutie Et Al. 2016

Knutie et al. 1 2 3 4 Galápagos mockingbirds tolerate introduced parasites 5 that affect Darwin’s finches 6 7 Sarah A. Knutie1,4*, Jeb P. Owen2, Sabrina M. McNew1, Andrew W. Bartlow1, 8 Elena Arriero3, Jordan M. Herman1, Emily DiBlasi1, Michael Thompson1, 9 Jennifer A.H. Koop1,5, and Dale H. Clayton1 10 11 12 13 Affiliations: 14 1Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA. 15 2Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA. 16 3Department of Zoology and Physical Anthropology, Complutense University of Madrid, E- 17 28040 Madrid, Spain. 18 4Current address: Department of Integrative Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 19 33620, USA. 20 5Current address: University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, Biology Department, Dartmouth, MA 21 02747, USA. 22 23 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Knutie et al. 24 Abstract. Introduced parasites threaten native host species that lack effective defenses. Such 25 parasites increase the risk of extinction, particularly in small host populations, like those on 26 islands. If some host species are tolerant to introduced parasites, this could amplify the risk of 27 the parasite to vulnerable host species. Recently, the introduced parasitic nest fly Philornis 28 downsi has been implicated in the decline of Darwin’s finch populations in the Galápagos Islands. 29 In some years, 100% of finch nests fail due to P. downsi; however, other common host species 30 nesting near Darwin’s finches, such as the endemic Galápagos mockingbird (Mimus parvulus), 31 appear to be less affected by P. downsi. 32 We compared effects of P. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

An Inter-Island Comparison of Darwin's Finches Reveals the Impact Of

RESEARCH ARTICLE An inter-island comparison of Darwin's finches reveals the impact of habitat, host phylogeny, and island on the gut microbiome 1 2 3,4 1 Wesley T. Loo , Rachael Y. Dudaniec , Sonia KleindorferID *, Colleen M. Cavanaugh * 1 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America, 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 3 College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, 4 Konrad Lorenz Research Center for Behaviour and Cognition and Department of Behavioural Biology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] (SK); [email protected] (CC) a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Darwin's finch species in the Galapagos Archipelago are an iconic adaptive radiation that offer a natural experiment to test for the various factors that influence gut microbiome com- OPEN ACCESS position. The island of Floreana has the longest history of human settlement within the archi- pelago and offers an opportunity to compare island and habitat effects on Darwin's finch Citation: Loo WT, Dudaniec RY, Kleindorfer S, Cavanaugh CM (2019) An inter-island comparison microbiomes. In this study, we compare gut microbiomes in Darwin's finch species on Flor- of Darwin's finches reveals the impact of habitat, eana Island to test for effects of host phylogeny, habitat (lowlands, highlands), and island host phylogeny, and island on the gut microbiome. (Floreana, Santa Cruz). We used 16S rRNA Illumina sequencing of fecal samples to assess PLoS ONE 14(12): e0226432. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0226432 the gut microbiome composition of Darwin's finches, complemented by analyses of stable isotope values and foraging data to provide ecological context to the patterns observed. -

Retarded Wing Molt in Black-Legged Kittiwakes

NOTES RETARDED WING MOLT IN BLACK-LEGGED KITTIWAKES STEVE N. G. HOWELL, Point ReyesBird Observatory,4990 ShorelineHighway, StinsonBeach, California 94970 CHRIS CORBEN, P.O. Box 2323, Rohnert Park, California 94927 Prebasicmolt of the primariesin mostspecies of northernhemisphere gulls occurs betweenApril and December(Dwight 1925, Grant 1986, Cramp and Simmons 1983, pers.obs.). Exceptions are mainlytransequatorial migrants, both those that molt primariesafter they have reachedtheir southernhemisphere winter grounds (e.g., Sabine'sGull, Xema sabini;Grant 1986) and thosethat suspendprimary molt betweenthe summerand winter grounds (e.g., Baltic Lesser Black-backed Gull, Larus fuscusfuscus; Jonsson 1998). The completesecond prebasic molt of the Black- leggedKittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) reportedly occurs from May to November,the adult prebasicmolt from June to December(Cramp and Simmons 1983, Baird 1994). Duringthe springof 1999 we notedadult Black-legged Kittiwakes in central Californiathat had not completedtheir prebasicprimary molt. Here we document and discussthis phenomenon. On 21 April 1999, off BodegaHead, SonomaCo., Corbennoted a kittiwakethat appearedto havean outerprimary only partially grown and that showeda largeblack patchalong the leadingedge of the underwing,anterior to the blackwing tip. We thoughtlittle of thisuntil, on 2 May 1999, we examineda kittiwakespecimen found freshlydead on SoutheastFarallon Island, San Francisco Co., on 11 March1999. On thisbird, primaries9 and 10 (P9-10) on the rightwing were worn and retainedand the new P8 was slightlyless than full length;on the left wing P10 was retained,P9 missing(presumed shed), and P8 full length.The tertialsand outer secondarieshad beenreplaced, while the middlesecondaries were retainedand worn;the innertwo subscapulars(nearest the body)had beenreplaced, while the outertwo were old and worn. -

Birds of Indiana

Birds of Indiana This list of Indiana's bird species was compiled by the state's Ornithologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Waterfowl: Swans, Geese, and Ducks Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Anser rossii Ross's Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta leucopsis Barnacle Goose Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Branta canadensis Canada Goose Cygnus olor Mute Swan X Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan SE Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Aix sponsa Wood Duck Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Gadwall Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mareca americana American Wigeon Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas acuta Northern Pintail Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck Aythya marila Greater Scaup Aythya affinis Lesser Scaup Somateria spectabilis King Eider Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoter Melanitta deglandi White-winged Scoter ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Melanitta americana Black Scoter Clangula hyemalis Long-tailed Duck Bucephala -

List of Icelandic Birds

BIRDWATCHING IN ICELAND FAMILLE / GENRE LATIN ICELANDIC ENGLISH BR ENGLISH AM FRENCH Gaviidae Gavia stellata Lómur Red-throated Diver Red-throated Loon Plongeon catmarin Gaviidae Gavia immer Himbrimi Great Northern Dive Common Loon Plongeon imbrin Podicipedidae Podiceps auritus Flórgoði Slavonian Grebe Horned Grebe Grèbe esclavon Procellariidae Fulmarus glacialis Fýll Fulmar Northern Fulmar Pétrel fulmar Procellariidae Puffinus Puffinus Skrofa Manx Shearwater Manx Shearwater Puffin des Anglais Hydrobatidae Oceanites oceanicus Hafsvala Wilson's Storm Petrel Wilson's Storm Petrel Océanite de Wilson Hydrobatidae Hydrobates pelagicus Stormsvala Storm Petrel Storm Petrel Pétrel tempéte Hydrobatidae Oceanodroma leucorhoa Sjósvala Leach´s Petrel Leach´s Storm Petrel Pétrel culblanc Sulidae Sula bassana Súla Gannet Gannet Fou de Bassan Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax carbo Dílaskarfur Cormorant Great Cormorant Grand cormoran Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax aristotelis Toppskarfur Shag Shag Cormoran huppé Ardeidae Ardea cinerea Gráhegri Grey Heron Grey Heron Héron cendré Anatidae Cygnus cygnus Álft Whooper Swan Whooper Swan Cygna sauvage Anatidae Anser brachyrhynchus Heiðagæs Pink-footed Goose Pink-footed Goose Oie à bec court Anatidae Anser albifrons Blesgæs White-fronted Goose White-fronted Goose Oie rieuse Anatidae Anser anser Grágæs Grey-lag Goose Grey-lag Goose Oie cendrée Anatidae Branta leucopsis Helsinki Barnacle Goose Barnacle Goose Bernache nonnette Anatidae Branta bernicla Margæs Brent Goose Brant Bernache cravant Anatidae Tadorna tadorna -

Vermont Bird Checklist Vermont Bird Records Committee Last Updated 1 December 2017

Vermont Bird Checklist Vermont Bird Records Committee www.vtecostudies.org/vbrc/ Last updated 1 December 2017 This checklist includes all species for which acceptable specimen, photographic, or written documentation exists for Vermont. The list has been approved by the Vermont Bird Records Committee and includes 387 species representing 22 orders and 62 families of birds. The names of the birds and their taxonomic arrangement follow the American Ornithological Society Check-list of North American Birds Seventh Edition (1998), 58th supplement (July 2017). STATUS E Extirpated - no longer occurs in Vermont but is not extinct H Hypothetical - single records that lack photo documentation or second party confirmation I Introduced X Extinct – once occurred in Vermont and is now extinct BREEDING * Species known to breed or to have bred in Vermont OCURRENCE Dates of occurrence are median arrival and departure dates and are indicated by numbers for months and by A, B, C, or D for weeks of the month. For example, 3C indicates presence in the third week of March. A plus sign (+) indicates species for which individuals are periodically encountered far outside their normal occurrence dates. REPORTING This checklist is based upon more than a century of documented observations. Reports that will expand this knowledge base are encouraged and appreciated. A documentation form can be found on the Vermont Bird Records Committee's web site listed above. Remember to carefully distinguish your bird from all similar, more common species. Photographs are not necessary but are particularly useful. Please submit documentation for: - Any species not listed on this checklist, or - Any species confirmed nesting which does not have an asterisk (*) after its name, or - Any species observed more than one month outside its occurrence dates (regardless of location) which does not have a plus sign (+) after its dates, or - Any species with the following codes (regardless of date): B Please submit documentation if this species is observed outside the Burlington area.