Anglo-Jewish Community During This Period and Is the First Monograph to Chart Its Contribution Systematically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

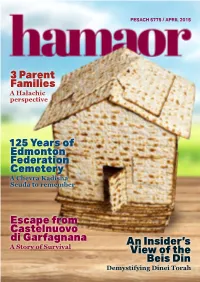

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

Some Highlights of the Mossad Harav Kook Sale of 2017

Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 By Eliezer Brodt For over thirty years, starting on Isru Chag of Pesach, Mossad HaRav Kook publishing house has made a big sale on all of their publications, dropping prices considerably (some books are marked as low as 65% off). Each year they print around twenty new titles. They also reprint some of their older, out of print titles. Some years important works are printed; others not as much. This year they have printed some valuable works, as they did last year. See here and here for a review of previous year’s titles. If you’re interested in a PDF of their complete catalog, email me at [email protected] As in previous years, I am offering a service, for a small fee, to help one purchase seforim from this sale. The sale’s last day is Tuesday. For more information about this, email me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog. What follows is a list and brief description of some of their newest titles. 1. הלכות פסוקות השלם,ב’ כרכים, על פי כת”י ששון עם מקבילות מקורות הערות ושינויי נוסחאות, מהדיר: יהונתן עץ חיים. This is a critical edition of this Geonic work. A few years back, the editor, Yonason Etz Chaim put out a volume of the Geniza fragments of this work (also printed by Mossad HaRav Kook). 2. ביאור הגר”א ,לנ”ך שיר השירים, ב, ע”י רבי דוד כהן ור’ משה רביץ This is the long-awaited volume two of the Gr”a on Shir Hashirim, heavily annotated by R’ Dovid Cohen. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

1 MS 142 AJ 416 Archives of the London Board of Shechita 1/1

1 MS 142 AJ 416 Archives of the London Board of Shechita 1/1 Correspondence with the Spanish and Portuguese Jews Congregation 1953-68 1/2 Correspondence with the Federation of Synagogues 1962-7 1/3 Correspondence: Jacob George 1967 Black and white photographs of the Israeli Restaurant 1/4 Correspondence: rents, electricity and other service charges 1967-8 1/5 Correspondence with the Liverpool Board of Shechita 1968-72 1/6 Correspondence with the Leeds Board of Shechita 1969-71 2/1 Correspondence with the Bournemouth Hebrew Congregation 1965-7 2/2 Correspondence: distribution of Kosher meat 1965-72 2/3 Correspondence: Kosher meat distribution depot 1969-71 2/4 Correspondence with Halford, Shead and Company 1970-1 2/5 Licences of shochetim 1968-9 3/1 General accounts with Joseph Sebag and Company 1965-9 3/2 General revenue account sheets 1969-70 3/3 Investment papers 1965-7 3/4 Investment papers, verification of stock 1966-7 3/5 Investment papers 1968 4 Correspondence: proposed new abattoir and Kosher meat distribution 1965-6 5/1 Correspondence: poultry abattoir 1970-2 5/2 Committee papers and associated papers 1971-2 6/1 Correspondence: terefah butchers 1970 6/2 Telegrams 1964-8 6/3 Correspondence, posters, black and white photographs: terefah butchers 7/1 Correspondence with the General Board of Shechita of Eire 1959-65 7/2 Correspondence: trade descriptions act of 1968 1969-71 8/1 Correspondence with the Board of Deputies of British Jews 1959-66 8/2 Papers relating to the case of M.Lederman 8/3 Union of Jewish Women report 1970 9/1 Correspondence -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

JEW HATRED Anti-Semitism in Emulate the Growth and Influence of Its European Counterparts

CJM OWALJUSIKWHS JEW HATRED Anti-Semitism in emulate the growth and influence of its European counterparts. Groups such as Britain Today the British National Party are scorned by the vast majority of Britons and are Anti-Semitism is, in many ways, the relatively powerless in the mainstream precursor of the racist attitudes now political process. projected by European societies on the The Far Right's influence, however, visible ethnic minorities within their on racial and political tension and midst. Jews remain the primary, violence, is manifest in localised areas of ideological, target for hard-core racists, power across the country. Racial attacks but the vast bulk of societal racism, in Tower Hamlets increased by over prejudice and actual physical attacks are 300% following the BNP's Millwall Edmonton Cemetery April 1990 directed against visible minority groups council seat election success in of Afro-Caribbean, India sub-continent, September '93. The Millwall victory (Nov '92); and the initial Allied air strikes or North African origin. This is confirmed (since overturned in the May '94 local against Iraq (Jan '91). by a number of recent opinion polls elections) gave an unprecedented boost The next highest increase followed conducted throughout Europe and Britain to the BNP's morale and public profile. the highly publicised desecration of the by the American Jewish Committee in Jewish cemetery in Carpentras, France which Jews were consistently viewed Anti-Semitic Incidents and Attacks (May '90). This is an indicator of the more favourably than other minority Anglo-Jewry's representative body, the influence of publicity on racist attacks, a groups. -

Culture-Sensitive Counselling, Psychotherapy and Support Groups in the Orthodox-Jewish Community: How They Work and How They Are Experienced

1 International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 50, 227-240. Culture-sensitive counselling, psychotherapy and support groups in the orthodox-Jewish community: How they work and how they are experienced. Kate Miriam Loewenthal and Marian Brooke Rogers Psychology Department Royal Holloway University of London Egham Surrey TW20 0EX 01784 443601 [email protected] 2 Culture-sensitive counselling, psychotherapy and support groups in the orthodox-Jewish community: How they work and how they are experienced. Abstract Background: There is political and scientific goodwill towards the provision of culture-sensitive support, but as yet little knowledge about how such support works and what are it strengths and difficulties in practice. Aims: To study groups offering culture-sensitive psychological and other support to the strictly- orthodox Jewish community in London. Methods: Semi-structured interviews with service providers, potential and actual users from the community, and professionals serving the community. Interviews asked about the aims, functioning and achievements of 10 support groups. Results: Thematic analysis identified seven important themes: admiration for the work of the groups; appreciation of the benefits of culture-sensitive services; concerns over confidentiality and stigma; concerns over finance and fundraising; concerns about professionalism; the importance of liaison with rabbinic authorities; need for better dissemination of information. Conclusions: The strengths and difficulties of providing culture-sensitive services in one community were identified. Areas for attention include vigilance regarding confidentiality, improvements in disseminating information, improvements in the reliability of funding, and attention to systematic needs assessment, and to the examination of efficacy of these forms of service provision. 3 Culture-sensitive counselling, psychotherapy and support groups in the orthodox-Jewish community: How they work and how they are experienced. -

Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz

A Bridge across the Tigris: Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz Our Rabbis tell us that on the death of Abaye the bridge across the Tigris collapsed. A bridge serves to unite opposite shores; and so Abaye had united the opposing groups and conflicting parties of his time. Likewise Dr. Hertz’s personality was the bridge which served to unite different communities and bodies in this country and the Dominions into one common Jewish loyalty. —Dayan Yechezkel Abramsky: Eulogy for Chief Rabbi Hertz.[1] I At his death in 1946, Joseph Herman Hertz was the most celebrated rabbi in the world. He had been Chief Rabbi of the British Empire for 33 years, author or editor of several successful books, and champion of Jewish causes national and international. Even today, his edition of the Pentateuch, known as the Hertz Chumash, can be found in most centrist Orthodox synagogues, though it is often now outnumbered by other editions. His remarkable career grew out of three factors: a unique personality and capabilities; a particular background and education; and extraordinary times. Hertz was no superman; he had plenty of flaws and failings, but he made a massive contribution to Judaism and the Jewish People. Above all, Dayan Abramsky was right. Hertz was a bridge, who showed that a combination of old and new, tradition and modernity, Torah and worldly wisdom could generate a vibrant, authentic and enduring Judaism. Hertz was born in Rubrin, in what is now Slovakia on September 25, 1872.[2] His father, Simon, had studied with Rabbi Esriel Hisldesheimer at his seminary at Eisenstadt and was a teacher and grammarian as well as a plum farmer. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

1. Figures Derived from Arthur Ruppin, the Jewish Fate and Future (London: 1940), Table 1, P

Notes 1 'BARBARISM AND BIGOTRY' 1. Figures derived from Arthur Ruppin, The Jewish Fate and Future (London: 1940), Table 1, p. 29. Ruppin's figures are for 1850. 2. Ibid. 3. Ibid. 4. On the emancipation of the Jews, see Jacob Katz, Out of the Ghetto: The Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870 (New York: 1978). 5. See M.C.N. Salbstein, The Emancipation of the Jews in Britain: The Question of the Admission of the Jews to Parliament, 1828-1860 (London: 1982). 6. See Jonathan Sarna, 'The Impact of the American Revolution on American Jews', in idem., ed., The American Jewish Experience (New York: 1986); Eli Faber, A Time for Planting: The First Migration 1654-1820 (Baltimore: 1992) and Hasia R. Diner,v4 Time for Gathering: The Second Migration 1820-1880 (Baltimore: 1992; vols. 1 and 2 of The Jewish People in America series). Recent works on American anti- semitism which, in our view, overstate its volume and importance include Leonard Dinnerstein, Antisemitism in America (New York: 1994), and Frederic Cople Jaher, A Scapegoat in the Wilderness: The Origins and Rise of Anti-Semitism in America (Cambridge, Mass.: 1994). On Australia, see Israel Getzler, Neither Toleration nor Favour: The Australian Chapter of Jewish Emancipation (Melbourne: 1970); Hilary L. Rubinstein, The Jews in Australia: A Thematic History. Volume One: 1788-1945 (Melbourne: 1991), pp. 3-24, 471-8. 7. See W.D. Rubinstein, A History of the Jews in the English-Speaking World: Great Britain (London: 1996), pp. 1-27. 8. For a comprehensive account of events see Jonathan Frankel, The Damascus Affair: 'Ritual Murder', Politics, and the Jews in 1840 (Cambridge: 1997). -

Activities of the World Jewish Congress 1975 -1980

ACTIVITIES OF THE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS 1975 -1980 REPORT TO THE SEVENTH PLENARY ASSEMBLY OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL GENEVA 5&0. 3 \N (i) Page I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Israel and the Middle East 5 Action against Anti-Semitism. 15 Soviet Jewry. 21 Eastern Europe 28 International Tension and Peace..... 32 The Third World 35 Christian-Jewish Relations 37 Jewish Communities in Distress Iran 44 Syria 45 Ethiopia 46 WJC Action on the Arab Boycott 47 Terrorism 49 Prosecution of Nazi Criminals 52 Indemnification for Victims of Nazi Persecution 54 The WJC and the International Community United Nations 55 Human Rights 58 Racial Discrimination 62 International Humanitarian Law 64 Unesco 65 Other international activities of the WJC 68 Council of Europe.... 69 European Economic Community 72 Organization of American States 73 III. CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 75 IV. RESEARCH 83 (ii) Page V. ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS Central Organs and Global Developments Presidency 87 Executive 87 Governing Board 89 General Council.... 89 New Membership 90 Special Relationships 90 Relations with Other Organizations 91 Central Administration 92. Regional Developments North America 94 Caribbean 97 Latin America 98 Europe 100 Israel 103 South East Asia and the Far East 106 Youth 108 WJC OFFICEHOLDERS 111 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS CONSTITUENTS 113 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS OFFICES 117 I. INTRODUCTION The Seventh Plenary Assembly of the World Jewish Congress in Jerusalem, to which this Report of Activities is submitted, will take place in a climate of doubt, uncertainty, and change. At the beginning of the 80s our world is rife with deep conflicts. We are perhaps entering a most dangerous decade.