Heritage Route Along Ethnic Lines: the Case of Penang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

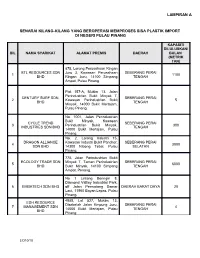

Lampiran a Senarai Kilang-Kilang Yang Beroperasi Memproses Sisa Plastik

LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KILANG-KILANG YANG BEROPERASI MEMPROSES SISA PLASTIK IMPORT DI NEGERI PULAU PINANG KAPASITI DILULUSKAN/ BIL NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT PREMIS DAERAH BULAN (METRIK TAN) 875, Lorong Perusahaan Ringan BTL RESOURCES SDN Juru 3, Kawasan Perusahaan SEBERANG PERAI 1 1100 BHD Ringan Juru, 14100 Simpang TENGAH Ampat, Pulau Pinang Plot 157-A, Mukim 13. Jalan Perindustrian Bukit Minyak 7, CENTURY SURF SDN. SEBERANG PERAI 2 Kawasan Perindustrian Bukit 5 BHD TENGAH Minyak, 14000 Bukit Mertajam, Pulau Pinang. No. 1001, Jalan Perindustrian Bukit Minyak, Kawasan CYCLE TREND SEBERANG PERAI 3 Perindustrian Bukit Minyak, 300 INDUSTRIES SDN BHD TENGAH 14000 Bukit Mertajam, Pulau Pinang. No. 2, Lorong Industri 15, DRAGON ALLIANCE Kawasan Industri Bukit Panchor, SEBERANG PERAI 4 3000 SDN BHD 14300 Nibong Tebal, Pulau SELATAN Pinang. 775, Jalan Perindustrian Bukit ECOLOGY TRADE SDN Minyak 7, Taman Perindustrian SEBERANG PERAI 5 6000 BHD Bukit Minyak, 14100 Simpang TENGAH Ampat, Penang. No 1 Lintang Beringin 8, Diamond Vallley Industrial Park, 6 EMBATECH SDN BHD off Jalan Permatang Damar DAERAH BARAT DAYA 20 Laut, 11960 Bayan Lepas, Pulau Pinang. 4988, Lot 527, Mukim 13, ESH RESOURCE Disebelah Jalan Kmpung Juru, SEBERANG PERAI 7 MANAGEMENT SDN 4 14000 Bukit Mertajam, Pulau TENGAH BHD Pinang 1ID10/18 LAMPIRAN A KAPASITI DILULUSKAN/ BIL NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT PREMIS DAERAH BULAN (METRIK TAN) No 4 Jalan Pala 6, Imperial GLOBECYCLE Industrial Park, Permatang SEBERANG PERAI 8 MANUFACTURING SDN 5 Tinggi, 14000 Bukit Mertajam, TENGAH BHD Pulau Pinang Plot 88A, Jalan Perindustrian Bkt Minyak, Kawasan IRM INDUSTRIES SEBERANG PERAI 9 Perindustrian Bukit Minyak, 1440 (PENANG) SDN BHD TENGAH 14000 Bukit Mertajam, Pulau Pinang NO.49, Lorong Mak Mandin 5/3, KHK RECYCLE SDN Kawasan Perindustrian Mak SEBERANG PERAI 10 2 BHD Mandin, 13400 Bukit Mertajam, TENGAH Pulau Pinang. -

Chapter 2: Penang's Macroeconomic Performance

Penang Economic and Development Report 2017/2018 22 Penang’s Macroeconomic 22 Performance 2.1 Output performance down from 8.7% in 2016 to 6.2% in 2017, it still exceeded the national average (1%) (Figure 2.2). The Penang’s economy has been growing at an average manufacturing and services sectors have been the rate of 5.6% over the past seven years (Figure main contributors to Penang’s GDP over the past 2.1). The state’s GDP growth slowed down by 0.3 seven years. In fact, Penang’s economic structure percentage point to 5.3% in 2017, mainly due to is mainly manufacturing- and services-oriented. In the negative 10.1% growth rate in the construction 2017, the services sector accounted for 49.3% of sector. Agricultural and manufacturing sectors GDP, while 44.8% was from the manufacturing sector registered the higher growth rates at 2.2% and 5.7%, (Table 2.1). However, the agricultural (2%), mining respectively, in 2017 compared to 2016, while the and quarrying (0.1%), and construction (2.6%) services sector remained at 5.6%. Although growth sectors were less significant, altogether accounting in Penang’s mining and quarrying sector had slowed for only 4.7% of Penang’s GDP. Figure 2.1 GDP growth in Malaysia and Penang, 2011–17 (at constant 2010 prices) 9.0 8.0 8.0 7.0 6.0 5.9 6.0 5.4 5.6 5.5 5.4 5.3 5.3 5.1 5.0 5.0 4.5 4.7 4.2 4.0 Percentage 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Malaysia Penang Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia. -

Seberang Perai(PDF)

31 October 2014 (Friday) Pacifico, Yokohama, Japan DATO’ MAIMUNAH MOHD SHARIF MUNICIPAL PRESIDENT MUNICIPAL COUNCIL OF SEBERANG PERAI (MPSP) PENANG, MALAYSIA To cut emissions 3 categories; energy efficiency, low carbon technologies and halt deforestation Malaysia is adopting an indicator of a voluntary reduction up to 40 percent in terms of emissions intensity of GDP by the year 2020 compared to 2005 levels National Green Technology Council chaired by Malaysia Prime Minister, Penang Green Council, MPSP Level- Green Office Vision is for energy, economy, environment & society 2 To assists local authorities, townships developers, designers and individuals in accessing whether developments carried out within the city contribute towards the reduction or decrease in Green House Gases (GHG) 3 Incentives Carbon trading & regulation Increase technology support Ecological footprint Engagement with the public or residents 4 Less pollution Better Health GOOD Cleaner transport QUALITY OF LIFE Protects water supply Controls Flooding Provide bio-diversity 5 THINK GLOBAL ACT LOCAL 6 SEGREGATION AT SOURCE WASTE GENERATORS PAY: To reduce cost at landfill To reduce wastage and as a source for other beneficial output/ activities To involve industries in recycling to reduce waste To encourage innovation and productions of new item base on industrial and commercial waste To increase the life- span of existing sanitary landfill To encourage zero waste, waste minimization and low carbon initiative. 7 MOU with Kawasaki, Japan- Waste to -

Design Conditions for PENANG/BAYAN LEPAS, Malaysia

2005 ASHRAE Handbook - Fundamentals (SI) © 2005 ASHRAE, Inc. Design conditions for PENANG/BAYAN LEPAS, Malaysia Station Information Hours +/- Time zone Station name WMO# Lat Long Elev StdP Period UTC code 1a 1b 1c 1d 1e 1f 1g 1h 1i PENANG/BAYAN LEPAS 486010 5.30N 100.27E 4 101.28 8.00 MLY 8201 Annual Heating and Humidification Design Conditions Humidification DP/MCDB and HR Coldest month WS/MCDB MCWS/PCWD Coldest Heating DB 99.6% 99% 0.4% 1% to 99.6% DB month 99.6% 99% DP HR MCDB DP HR MCDB WS MCDB WS MCDB MCWS PCWD 2 3a3b4a4b4c4d4e4f5a5b5c5d6a6b 10 22.8 23.1 18.5 13.4 27.0 19.3 14.0 27.1 7.4 26.3 6.1 27.6 1.1 350 Annual Cooling, Dehumidification, and Enthalpy Design Conditions Hottest Cooling DB/MCWB Evaporation WB/MCDB MCWS/PCWD Hottest month 0.4% 1% 2% 0.4% 1% 2% to 0.4% DB month DB range DB MCWB DB MCWB DB MCWB WB MCDB WB MCDB WB MCDB MCWS PCWD 7 8 9a 9b 9c 9d 9e 9f 10a 10b 10c 10d 10e 10f 11a 11b 4 6.5 32.9 26.2 32.3 26.0 32.0 26.0 27.6 31.2 27.2 30.7 27.0 30.5 3.7 270 Dehumidification DP/MCDB and HR Enthalpy/MCDB 0.4% 1% 2% 0.4% 1% 2% DP HR MCDB DP HR MCDB DP HR MCDB Enth MCDB Enth MCDB Enth MCDB 12a 12b 12c 12d 12e 12f 12g 12h 12i 13a 13b 13c 13d 13e 13f 26.7 22.2 29.5 26.2 21.7 29.1 26.1 21.5 29.0 87.7 31.5 86.3 31.0 85.2 30.6 Extreme Annual Design Conditions Extreme Extreme Annual DB n-Year Return Period Values of Extreme DB Extreme Annual WS Max Mean Standard deviation n=5 years n=10 years n=20 years n=50 years 1% 2.5% 5%WB Max Min Max Min Max Min Max Min Max Min Max Min 14a 14b 14c 15 16a 16b 16c 16d 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017 What did we spot on the Sarawak and regional heritage scene in the last five months? SARAWAK Land clearing observed early March just uphill from the Bongkissam archaeological site, Santubong, raised alarm in the heritage-sensitive community because of the known archaeological potential of the area (for example, uphill from the shrine, partial excavations undertaken in the 1950s-60s at Bukit Maras revealed items related to the Indian Gupta tradition, tentatively dated 6 to 9th century). The land in question is earmarked for an extension of Santubong village. The bulldozing was later halted for a few days for Sarawak Museum archaeologists to undertake a rapid surface assessment, conclusion of which was that “there was no (…) artefact or any archaeological remains found on the SPK site” (Borneo Post). Greenlight was subsequently given by the Sarawak authorities to get on with the works. There were talks of relocating the shrine and, in the process, it appeared that the Bongkissam site had actually never been gazetted as a heritage site. In an e-statement, the Sarawak Heritage Society mentioned that it remained interrogative and called for due diligences rules in preventive archaeology on development sites for which there are presumptions of historical remains. Dr Charles Leh, Deputy Director of the Sarawak Museum Department mentioned an objective to make the Santubong Archaeological Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2020. (our Nov.2016-Feb.2017 Newsletter reported on this latter project “Extension project near Santubong shrine raises concerns” – Borneo Post, 22 March 2017 “Bongkissam shrine will be relocated” – Borneo post, 23 March 2017 “Gazette Bongkissam shrine as historical site” - Borneo Post. -

Seberang Perai Low Carbon City Definition

Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy : Urban adaptation to climate change 21st March 2019 Climate Change Actions : Seberang Perai’s Experience on Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Speaker: Ahmad Zabri Mohamed Sarajudin Director of Crisis Management Department, Seberang Perai SEBERANG PERAI EXPERIENCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE SEBERANG PERAI EXPERIENCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE 3,256 171,428 houses 162 cars people affected trapped affected 9,636 358 1 Person 15 cars people Died houses affected relocated affected 362mm 15,942 tonnes rainfall within 12 days Solid Waste 6 consecutive for collected hours recovery RM11.3M 11,323 1,194 trees Economic Warriors uprooted Loss SEBERANG PERAI Aspiring City Of Tomorrow Citizen Cashless Public Participation Payment Reporting System System System Smart Industry Data 4.0 Exchange Smart Street Platform Light Flood Management Digital System Signage Smart & Smart Sustainable Parking Building Smart & Smart Smart Solid Smart Integrated Sustainable Traffic Waste Learning Command Hawkers Complex Light Management Center Center Vision Seberang Perai Resilient, Inclusive, Green, Competitive and Technology Driven Smart City Mision To provide urban service, development planning and infrastructure efficiently, effectively and responsive to the needs of the community in Seberang Perai Corporate Value We work collaboratively across organization and communities to improve outcome, value for money and services 7Ps INCLUSIVE PARTNERSHIP Guiding Principles MODEL “City for all” •Improve governance and inclusiveness •Accessibility -

Muzikološki Z B O R N I K X L I V

MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL X L I V / 1 ZVEZEK/VOLUME L J U B L J A N A 2 0 0 8 MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK • MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL XLIV/1 • MUSICOLOGICAL ZBORNIK ANNUAL MUZIKOLOŠKI APLIKATIVNA ETNOMUZIKOLOGIJA ISSN 0580-373X APPLIED ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 9 770580 373009 MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL X L I V / 1 ZVEZEK/VOLUME L J U B L J A N A 2 0 0 8 APLIKATIVNA ETNOMUZIKOLOGIJA APPLIED ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 1 Izdaja • Published by Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Urednik zvezka • Edited by Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana) Urednik • Editor Matjaž Barbo (Ljubljana) Asistent uredništva • Assistant Editor Jernej Weiss (Ljubljana) Uredniški odbor • Editorial Board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Jean-Marc Chouvel (Reims) David Hiley (Regensburg) Nikša Gligo (Zagreb) Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Niall O’Loughlin (Loughborough) Leon Stefanija (Ljubljana) Andrej Rijavec (Ljubljana), častni urednik • honorary editor Uredništvo • Editorial Address Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofska fakulteta Aškerčeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija e-mail: [email protected] http://www.ff.uni-lj.si Prevajanje • Translation Andrej Rijavec Cena • Price 10 € / 20 € (other countries) Tisk • Printed by Birografika Bori d.o.o., Ljubljana Naklada 500 izvodov• Printed in 500 copies Rokopise, publikacije za recenzije, korespondenco in naročila pošljite na naslov izdajatelja. Prispevki naj bodo opremljeni s kratkim povzetkom (200-300 besed), izvlečkom (do 50 besed), ključnimi besedami in kratkimi podatki o avtorju. Nenaročenih rokopisov ne vračamo. Manuscripts, publications for review, correspondence and annual subscription rates should be sent to the editorial address. Contributions should include a short summary (200-300 words), abstract (not more than 50 words) keywords and a short biographical noe on the author. -

ASPEN (GROUP) HOLDINGS LIMITED Company Registration No.: 201634750K (Incorporated in the Republic of Singapore)

ASPEN (GROUP) HOLDINGS LIMITED Company Registration No.: 201634750K (Incorporated in the Republic of Singapore) RESPONSE TO QUESTIONS FROM SECURITIES INVESTORS ASSOCIATION (SINGAPORE) ON ANNUAL REPORT 2019 The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of Aspen (Group) Holdings Limited (the “Company” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”) refers to the questions raised by the Securities Investors Association (Singapore) (“SIAS”) relating to the Company’s Annual Report for the financial year ended 31 December 2019 (“Annual Report 2019”) and appends the replies as follows: SIAS Question 1: As noted in the Corporate milestones, in 2019, the group completed the Vervea commercial precinct which is the first phase of Aspen Vision City’s masterplan. This was followed by the opening of Ikea and IKEA Meeting Place in March 2019 and December 2019 respectively. The group is targeting to complete Vertu Resort and Beacon Executive Suites in 2021, although the completion dates may be delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Other projects include: - Vivo Executive Apartment (expected TOP: 2023) - Viluxe (Phase1) (expected TOP: 2023) - Vogue Lifestyle Residence As at 31 December 2019, TRI PINNACLE and Beacon Executive Suites have achieved sales of 91% and 64% respectively. Vervea and Vertu Resort are 89% and 71% sold respectively. (i) With sales of 91% achieved, there are approximately 110-120 units left at TRI PINNACLE. What are management’s plans for the remaining units of TRI PINNACLE? The TOP for the project was obtained in December 2018. (ii) Can management confirm that it is the group’s strategy to sell the units in commercial developments (for example, Vervea) and thus it would not be building up an investment portfolio for recurring income at this stage of the group’s growth? It was stated the group envisioned the investments in Aloft Hotel, the Regional Integrated Shopping Centre and the Shah Alam Integrated Logistics Hub would contribute to its recurring income in years to come. -

High-Level Roundtable Discussion on Smart Sustainable Cities World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization

High-level Roundtable Discussion on Smart Sustainable Cities World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization Mr. Kyong-yul Lee Secretary General WeGO | World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization WHAT IS WeGO? INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF 131 CITIES + 5 NATIONAL ICT INSTITUTIONS + 7 CORPORATE MEMBERS • President City: Seoul • Executive Vice President City: Makati • Vice President Cities: Addis Ababa, Beyoğlu, Ha Noi, Jakarta, Mexico City, Moscow, Ulyanovsk Region • Executive Committee Member Cities: Bucharest, Chengdu, Goyang, Hebron, Khartoum State, Kigali, Nairobi, Pittsburgh, Seberang Perai, Ulaanbaatar • Regional Offices: Asia, Europe, Latin America, Mediterranean • Secretariat: Seoul Global Center 7F, South Korea WeGO | World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization WeGO MEMBERS 20 5 44 65 143 MEMBERS WORLDWIDE VISION: Smart Sustainable Cities for All • Innovative cities that leverage digital technology and connectivity to improve quality of life, efficiency of urban operation and services, and economic prosperity for all citizens, while ensuring long-term economic, social and environmental sustainability MISSION • To promote and facilitate the transformation of cities to Smart Sustainable Cities worldwide; • To be a global platform for cities to enhance their digital capabilities and leverage their innovation potentials in order to develop transformative solutions; and • To foster international exchange, cooperation, and learning among cities. WeGO | World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization WeGO ACTIVITIES 1. Capacity Building 3. Knowledge -

Aspen Group Together with Oxley Holdings Aim to Bring Mixed-Use Integrated Development with Modern Conveniences to Air Itam

PRESS RELEASE - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Aspen Group together with Oxley Holdings aim to bring mixed-use integrated development with modern conveniences to Air Itam ▪ The Group together with Oxley Holdings Limited are investing RM165 mil to acquire a total of 7 pieces of freehold land measuring 29.05 acres (1.27 million sq ft) in Paya Terubong via a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Geo Valley Sdn Bhd ▪ The proposed development is a mixed-use development comprising residential towers, service apartments, retail lots and a community centre ▪ The land is strategically located within a matured suburban township serving a community as many as 400,000 people. ▪ The development will benefit from existing daily lifestyle amenities and well- connected excellent infrastructure in a matured residential township, including the ongoing Jalan Bukit Kukus Highway Project which will eventually link the Air Itam township to the FTZ area of Bayan Lepas, Penang International Airport and two Penang Bridges via the future Pan Island Link Singapore, 22 June 2019 – Aspen (Group) Holdings Limited (“Aspen” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”), today announced that its subsidiary company, Aspen Park Hills Sdn Bhd signed a conditional sales and purchase agreement with Geo Valley Sdn. Bhd., to acquire a total of seven pieces of freehold land measuring 29.05 acres in Paya Terubong for RM165mil. Geo Valley Sdn. Bhd. will also invest 25% equity in Aspen Park Hills Sdn Bhd. Parts of the land are currently approved by the local council for mixed development and for the construction of part of the Jalan Bukit Kukus paired road linking Thean Teik Highway from Air Itam to Jalan Paya Terubong. -

Penang Travel Tale

Penang Travel Tale The northern gateway to Malaysia, Penang’s the oldest British settlement in the country. Also known as Pulau Pinang, the state capital, Georgetown, is a UNESCO listed World Heritage Site with a collection of over 12,000 surviving pre-war shop houses. Its best known as a giant beach resort with soft, sandy beaches and plenty of upscale hotels but locals will tell you that the island is the country’s unofficial food capital. SIM CARDS AND DIALING PREFIXES Malaysia’s three main cell phone service providers are Celcom, Digi and WEATHER Maxis. You can obtain prepaid SIM cards almost anywhere – especially Penang enjoys a warm equatorial climate. Average temperatures range inside large-scale shopping malls. Digi and Maxis are the most popular between 29°C - 35 during the day and 26°C - 29°C during the night; services, although Celcom has the most widespread coverage in Sabah however, being an island, temperatures here are often higher than the and Sarawak. Each state has its own area code; to make a call to a mainland and sometimes reaches as high as 35°C during the day. It’s best landline in Penang, dial 04 followed by the seven-digit number. Calls to not to forget your sun block – the higher the SPF, the better. It’s mostly mobile phones require a three-digit prefix, (Digi = 016, Maxis = 012 and sunny throughout the day except during the monsoon seasons when the Celcom = 019) followed by the seven digit subscriber number. island experiences rainfall in the evenings. http://www.penang.ws /penang-info/clim ate.htm CURRENCY GETTING AROUND Malaysia coinage is known as the Ringgit Malaysia (MYR).