Perspectives on Neighborhood Transition in Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for Reconnecting Southeast Washington DC

1 Reimagining DC 295 as a vital multi modal corridor: The Case for Reconnecting Southeast Washington DC Jonathan L. Bush A capstone thesis paper submitted to the Executive Director of the Urban & Regional Planning Program at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Masters of Professional Studies in Urban & Regional Planning. Faculty Advisor: Howard Ways, AICP Academic Advisor: Uwe S. Brandes, M.Arch © Copyright 2017 by Jonathan L. Bush All Rights Reserved 2 ABSTRACT Cities across the globe are making the case for highway removal. Highway removal provides alternative land uses, reconnects citizens and natural landscapes separated by the highway, creates mobility options, and serves as a health equity tool. This Capstone studies DC 295 in Washington, DC and examines the cases of San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway, Milwaukee’s Park East Freeway, New York City’s Sheridan Expressway and Seoul, South Korea’s Cheonggyecheon Highway. This study traces the history and the highway removal success using archival sources, news circulars, planning documents, and relevant academic research. This Capstone seeks to provide a platform in favor DC 295 highway removal. 3 KEYWORDS Anacostia, Anacostia Freeway, Anacostia River, DC 295, Highway Removal, I-295, Kenilworth Avenue, Neighborhood Planning, Southeast Washington DC, Transportation Planning, Urban Infrastructure RESEARCH QUESTIONS o How can Washington’s DC 295 infrastructure be modified to better serve local neighborhoods? o What opportunities -

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

ROUTES LINE NAME Sunday Supplemental Service Note 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington

Sunday Supplemental ROUTES LINE NAME Note Service 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington Blvd-Dunn Loring Sunday 2B Fair Oaks-Jermantown Rd Sunday 3A Annandale Rd Sunday 3T Pimmit Hills No Service 3Y Lee Highway-Farragut Square No Service 4A,B Pershing Drive-Arlington Boulevard Sunday 5A DC-Dulles Sunday 7A,F,Y Lincolnia-North Fairlington Sunday 7C,P Park Center-Pentagon No Service 7M Mark Center-Pentagon Weekday 7W Lincolnia-Pentagon No Service 8S,W,Z Foxchase-Seminary Valley No Service 10A,E,N Alexandria-Pentagon Sunday 10B Hunting Point-Ballston Sunday 11Y Mt Vernon Express No Service 15K Chain Bridge Road No Service 16A,C,E Columbia Pike Sunday 16G,H Columbia Pike-Pentagon City Sunday 16L Annandale-Skyline City-Pentagon No Service 16Y Columbia Pike-Farragut Square No Service 17B,M Kings Park No Service 17G,H,K,L Kings Park Express Saturday Supplemental 17G only 18G,H,J Orange Hunt No Service 18P Burke Centre Weekday 21A,D Landmark-Bren Mar Pk-Pentagon No Service 22A,C,F Barcroft-South Fairlington Sunday 23A,B,T McLean-Crystal City Sunday 25B Landmark-Ballston Sunday 26A Annandale-East Falls Church No Service 28A Leesburg Pike Sunday 28F,G Skyline City No Service 29C,G Annandale No Service 29K,N Alexandria-Fairfax Sunday 29W Braeburn Dr-Pentagon Express No Service 30N,30S Friendship Hghts-Southeast Sunday 31,33 Wisconsin Avenue Sunday 32,34,36 Pennsylvania Avenue Sunday 37 Wisconsin Avenue Limited No Service 38B Ballston-Farragut Square Sunday 39 Pennsylvania Avenue Limited No Service 42,43 Mount -

Downtown East Re-Urbanization Strategy Executive Summary 1St St Nw St 1St North Cap I Tol St 4Th St Nw St 4Th

AUGUST 2019 D O W N T O W N RE-URBANIZATION E A S T STRATEGY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Dear Residents and Stakeholders: As Mayor of Washington, DC, I am pleased to In addition to thanking the residents who present our Downtown East Re-Urbanization contributed to this plan, I would like to Strategy. Located on the iconic doorstep acknowledge the DC Office of Planning for of Union Station and the crossroads of our leading the effort along with several District Downtown, Mount Vernon Triangle, and NoMA agencies, including the District Department neighborhoods, Downtown East represents a of Transportation, the District Department of bustling gateway to our city’s geographic heart. Parks and Recreation, the District Department of General Services, and the District Department of Over the past few decades, much of our center city Energy and the Environment. This core team of area has witnessed a resurgence of investment partner agencies has, over the past several years, and opportunity, while Downtown East has engaged with residents, partners in the federal largely lagged. Now, however, the area is poised government, and community stakeholders to to bloom, with renewed interest, a growing establish this future for Downtown East. Moving population, large-scale development (complete forward, this Strategy will require a range of or under construction), and transformative public implementers across many sectors. The District space projects—like the New Jersey/New York government, the Mt. Vernon Triangle Community Avenue Streetscape project—which attempts to Improvement District (CID), the NoMA Business heal physical barriers and is expected to provide Improvement District (BID), the Downtown BID, safe pedestrian connections and a vibrant place property owners, developers, civic associations, for all our residents and visitors to enjoy. -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Building in the Aftermath N AUGUST 29, HURRICANE KATRINA dialogue that can inform the processes by made landfall along the Gulf Coast of which professionals of all stripes will work Othe United States, and literally changed in unison to repair, restore, and, where the shape of our country. The change was not necessary, rebuild the communities and just geographical, but also economic, social, landscapes that have suffered unfathomable and emotional. As weeks have passed since destruction. the storm struck, and yet another fearsome I am sure that I speak for my hurricane, Rita, wreaked further damage colleagues in these cooperating agencies and on the same region, Americans have begun organizations when I say that we believe to come to terms with the human tragedy, good design and planning can not only lead and are now contemplating the daunting the affected region down the road to recov- question of what these events mean for the ery, but also help prevent—or at least miti- Chase W. Rynd future of communities both within the gate—similar catastrophes in the future. affected area and elsewhere. We hope to summon that legendary In the wake of the terrorist American ingenuity to overcome the physi- attacks on New York and Washington cal, political, and other hurdles that may in 2001, the National Building Museum stand in the way of meaningful recovery. initiated a series of public education pro- It seems self-evident to us that grams collectively titled Building in the the fundamental culture and urban char- Aftermath, conceived to help building and acter of New Orleans, one of the world’s design professionals, as well as the general great cities, must be preserved, revitalized, public, sort out the implications of those and protected. -

Adams Morgan Vision Framework and Eclectic Built Environment

INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE PROCESS Steeped in history and cultural diversity, layered with by the DC Council, the Vision Framework was conceived At the outset of the project, the Office of Planning well-maintained historic architecture and a mix of as a lighter, briefer, strategic planning effort which formed an Advisory Committee for the Adams Morgan housing types, and emboldened by a strong sense of through targeted public outreach and data analysis Vision Framework and worked closely with them to community pride, cultural vibrancy, and civic activism, would deliver a high level vision for the neighborhood get robust and detailed feedback and to formalize the Adams Morgan is one of Washington, D.C.’s most unique and identify key implementation items to direct public proposals and goals presented in this Framework. The neighborhoods. The neighborhood’s residents add to investment and private actions. The Vision Framework Advisory Committee was composed of community its layered identity and are its greatest asset. Among model was simultaneously piloted in both the Van Ness members, business owners, historians, and elected longtime residents and artists who preserved and and Adams Morgan neighborhoods. officials who are listed in the acknowledgments on the insulated the bohemian feeling of Adams Morgan from last page. the norm of other District neighborhoods exists newer The catalyst for studying the Adams Morgan residents including young professionals attracted by neighborhood was the activism of some residents and The process began with data collection of existing the same lively and progressive culture, but seeking civic organizations who requested that the District conditions and the creation of a Neighborhood Profile an amenity-rich neighborhood in which to live. -

Historic District Vision Faces Debate in Burleith

THE GEORGETOWN CURRENT Wednesday, June 22, 2016 Serving Burleith, Foxhall, Georgetown, Georgetown Reservoir & Glover Park Vol. XXV, No. 47 D.C. activists HERE’S LOOKING AT YOU, KID Historic district vision sound off on faces debate in Burleith constitution ciation with assistance from Kim ■ Preservation: Residents Williams of the D.C. Historic By CUNEYT DIL Preservation Office. The goal of Current Correspondent divided at recent meeting the presentation, citizens associa- By MARK LIEBERMAN tion members said, was to gather Hundreds of Washingtonians Current Staff Writer community sentiments and turned out for two constitutional address questions about the impli- convention events over the week- Burleith took a tentative step cations of an application. Many at end to give their say on how the toward historic district designa- the meeting appeared open to the District should function as a state, tion at a community meeting benefits of historic designation, completing the final round of pub- Thursday — but not everyone was while some grumbled that the pre- lic comment in the re-energized immediately won over by the sentation focused too narrowly on push for statehood. prospect. positive ramifications and not The conventions, intended to More than 40 residents of the enough on potential negative ones. hear out practical tweaks to a draft residential neighborhood, which Neighborhood feedback is cru- constitution released last month, lies north and west of George- cial to the process of becoming a brought passionate speeches, and town, turned out for a presentation historic district, Williams said dur- even songs, for the cause. The from the Burleith Citizens Asso- See Burleith/Page 2 events at Wilson High School in Tenleytown featured guest speak- ers and politicians calling on the city to seize recent momentum for Shelter site neighbors seek statehood. -

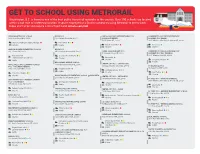

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Year of Anacostia Council Testimony EAP Draft 2 FINAL

COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Committee on Public Works and Transportation The Year of the Anacostia Statement of Beth Purcell On behalf of the Capitol Hill Restoration Society January 11, 2018 My name is Beth Purcell, and I am testifying on behalf of the Capitol Hill Restoration Society (CHRS), the largest civic organization on Capitol Hill. Since 1955 CHRS has advocated for the welfare of Capitol Hill. Today I would like to talk to you about one of DDOT's most significant accomplishments, the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail, particularly the section near RFK Stadium, and a threat to the trail, ironically coming from DDOT itself. Anacostia Riverwalk Trail The Anacostia Riverwalk Trail is a backbone of the Anacostia Waterfront, connecting residents, visitors and communities to the river, to one another and to numerous commercial and recreational destinations. All of the 20 planned miles are complete, and the trail is offers seamless, scenic travel on both sides of the river for pedestrians and bicyclists between Nationals Park, Historic Anacostia, RFK Stadium, Barney Circle, and the Navy Yard. The attached map shows part of the completed trail route (in red), running on the east and west side or the Anacostia River. Threat to the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail from DDOT's proposed "Park Road" But DDOT and EventsDC threaten Anacostia Riverwalk Trail by their plans to build a new road, called the "Park Drive," from Benning Road to Barney Circle, through Anacostia Park along the west bank of the river, running through the natural resource areas adjacent to RFK Stadium and Congressional Cemetery.1 Many of us on Capitol Hill believe that the so- called Park Drive will be a commuter road. -

Transportation Impact Study American University – Tenley Campus Washington, DC

Preliminary Transportation Impact Study American University – Tenley Campus Washington, DC August 29, 2011 Prepared by: 1140 Connecticut Avenue 3914 Centreville Road 7001 Heritage Village Plaza Suite 600 Suite 330 Suite 220 Washington, DC20036 Chantilly, VA20151 Gainesville, VA20155 Tel: 202.296.8625 Tel: 703.787.9595 Tel: 703.787.9595 Fax: 202.785.1276 Fax: 703.787.9905 Fax: 703.787.9905 www.goroveslade.com This document, together with the concepts and designs presented herein, as an instrument of services, is intended for the specific purpose and client for which it was prepared. Reuse of and improper reliance on this document without written authorization by Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc., shall be without liability to Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc. Preliminary Transportation Impact Study – Tenley Campus Gorove/Slade Associates TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction & Site Review .....................................................................................................................................................