A Welsh Neolithic Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeology Wales

Archaeology Wales Proposed Wind Turbine at Nant-y-fran, Cemaes, Isle of Anglesey Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment Adrian Hadley Report No. 1517 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall, Great Oak Street, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] Web: www.arch-wales.co.uk Archaeology Wales Proposed Wind Turbine at Nant-y-fran, Cemaes, Isle of Anglesey Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment Prepared for Engena Ltd Edited by: Kate Pitt Authorised by: Mark Houliston Signed: Signed: Position: Project Manager Position: Managing Director Date: 04.11.16 Date: 04.11.16 Adrian Hadley Report No. 1517 November 2016 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall, Great Oak Street, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] Web: www.arch-wales.co.uk NANT-Y-FRAN TURBINE: ARCHAEOLOGY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE 1 Introduction This impact assessment has been produced following scoping in order to determine the likely significance of the effect of the proposed development upon the cultural heritage resource within the application site and the wider landscape. The work is intended to form a Cultural Heritage chapter of an Environmental Statement. The proposed scheme comprises a single wind turbine, approximately 77m high to tip of the blade, at Nant-y-fran, Cemaes, Anglesey, LL67 0LS. The impact assessment for the turbine has been commissioned by Engena Limited (The Old Stables, Bosmere Hall, Creeting St Mary, Suffolk, IP6 8LL). The local planning authority is the Isle of Anglesey County Council. The planning reference is 20C27B/SCR. -

Small Works, Big Stories. Methodological Approaches To

Aberystwyth University Small works, big stories. Methodological approaches to photogrammetry through crowd sourcing experiences Griffiths, Seren; Edwards, Ben; Wilson, Andrew; Karl, Raimund; Labrosse, Frédéric; La Trobe-Bateman, Emily; Miles, Helen; Möller, Katharina; Roberts, Jonathan; Tiddeman, Bernie Published in: Internet Archaeology DOI: 10.11141/ia.40.7.2 Publication date: 2015 Citation for published version (APA): Griffiths, S., Edwards, B., Wilson, A., Karl, R., Labrosse, F., La Trobe-Bateman, E., Miles, H., Möller, K., Roberts, J., & Tiddeman, B. (2015). Small works, big stories. Methodological approaches to photogrammetry through crowd sourcing experiences. Internet Archaeology, 40. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.7.2 Document License CC BY General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 25. Mar. 2020 Griffiths, S. et al. (2015) ‘Small Works, Big Stories. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Parte a Nombre DNI Núm. Id Investig A.1. Sit Organis Dpto. / C Direcció Teléfon Categor Espec. Palabra A.2. Fo Li Lic. Filo D

Fecha del CVA 2020 Parte A. DATOS PERSONALES Nombre y Apellidos ARTURO RUIZ RODRIGUEZ DNI Edad Núm. identificación del Researcher ID investiggador Scopus Author ID Código ORCID A.1. Situación profesional actual Organismo Universidad de Jaén Dpto. / Centro Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Arqueoología Iberica Dirección Edif. C6 Campus Las Lagunillas CP 23071 Jaén España Teléfono 683750016 Correo electrónico arruiz ujaen.es Categoría profesional Catedrático Universidad. Area Prehistoria Fecha inicio 1991 Espec. cód. UNESCO Palabras clave A.2. Formación académica (título, institución, fecha) Liicenciatura/Grado/Doctorado Universidad Año Lic. Filosofía y Letras. Geografía e Historia Univ. Granada 1973 Doctor Historia Univ. Granada 1978 A.3. Indicadores generales de calidad de la producción científica -Seis Tramos de Investigación. El último concedido en 2010. -Tesis dirigidas: 13. La ultima en 2019 - Publicaciones en Congresos, Revistas y Editoriales de primer nivel: Ostraka (Perugia), EPOCH Publication, Archivo Español de Arqueología (Madrid), Roman Frontiers Studies, Oxbow Books (Oxford), Routledge studies in archaeology (New York) Quasar(Roma), Hermann (Paris), Bretschneider (Roma), Madrider Mitteilungen (Mainz) Cambridge University Press. Papers of the EAA, Barker and Lloyd, British School at Rome, Studia Celtica (Wales), Complutum, Antiquity, Quaternary Internaational, etc Parte B. RESUMEN LIBRE DEL CURRÍCCULUM Desde 1974 trabajo en el estudio del territorio ibero en el Alto valle del rio Guadalquivir (SE de la Península Ibérica) en el análisis del poblamiento y su desarrollo en función de las formas políticas que formula la aristocracia desde el s. VII al I a.n.e. En ese marco el proyecto de trabajo ha analizado la cconstrucción de los linajes gentilicios clientelares y su evolución hacia formas de dependencia aristocratica y su relación con la aparición del oppidum. -

Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council Joint Local Development Plan

Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council Joint Local Development Plan SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL ADDENDUM REPORT December 2016 CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose and Structure of the Report 2.0 SA OF PROPOSED MATTERS ARISING CHANGES 2 3.0 SUMMARY AND NEXT STEPS 2 4.0 SCHEDULES OF MATTERS ARISING CHANGES AND SCREENING 3 OPINION - WRITTEN STATEMENT SA of Proposed Matters Arising Changes Written Statement APPENDIX 1 377 SA Screening housing allocation, Casita, Beaumaris (T32) 5.0 SCHEDULES OF MATTERS ARISING CHANGES AND SCREENING 379 OPINION – PROPOSALS MAPS SA of Proposed Matters Arising Changes Proposal Maps 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council (the Councils) are currently preparing a Joint Local Development Plan (JLDP) for the Gwynedd and Anglesey Local Planning Authority Areas. The JLDP will set out the strategy for development and land use in Anglesey and Gwynedd for the 15 year period 2011- 2026. It will set out policies to implement the strategy and provide guidance on the location of new houses, employment opportunities and leisure and community facilities. 1.2 The Councils have been undertaking Sustainability Appraisal (SA) incorporating Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) since 2011 to inform the preparation of the JLDP. The SA process for the JLDP has produced the following reports to date: . Scoping Report July 2011 - which should be used for consultation on the scope of the SA/SEA - placed on public consultation on 21/07/2011 for a period of 7 weeks. A notice was placed in local newspapers presenting information regarding the consultation period and invited interested parties to submit written comments about the Report. -

Download Date 30/09/2021 08:59:09

Reframing the Neolithic Item Type Thesis Authors Spicer, Nigel Christopher Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 30/09/2021 08:59:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/13481 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Reframing the Neolithic Nigel Christopher SPICER Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Archaeological Sciences School of Life Sciences University of Bradford 2013 Nigel Christopher SPICER – Reframing the Neolithic Abstract Keywords: post-processualism, Neolithic, metanarrative, individual, postmodernism, reflexivity, epistemology, Enlightenment, modernity, holistic. In advancing a critical examination of post-processualism, the thesis has – as its central aim – the repositioning of the Neolithic within contemporary archaeological theory. Whilst acknowledging the insights it brings to an understanding of the period, it is argued that the knowledge it produces is necessarily constrained by the emphasis it accords to the cultural. Thus, in terms of the transition, the symbolic reading of agriculture to construct a metanarrative of Mesolithic continuity is challenged through a consideration of the evidential base and the indications it gives for a corresponding movement at the level of the economy; whilst the limiting effects generated by an interpretative reading of its monuments for an understanding of the social are considered. -

Bibliography Updated 2016

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography Northwest Wales 2016 Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Select Bibliography Northwest Wales - Neolithic Baynes, E. N., 1909, The Excavation of Lligwy Cromlech, in the County of Anglesey, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. IX, Pt.2, 217-231 Bowen, E.G. and Gresham, C.A. 1967. History of Merioneth, Vol. 1, Merioneth Historical and Record Society, Dolgellau, 17-19 Burrow, S., 2010. ‘Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey: alignment, construction, date and ritual’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, Vol. 76, 249-70 Burrow, S., 2011. ‘The Mynydd Rhiw quarry site: Recent work and its implications’, in Davis, V. & Edmonds, M. 2011, Stone Axe Studies III, 247-260 Caseldine, A., Roberts, J.G. and Smith, G., 2007. Prehistoric funerary and ritual monuments survey 2006-7: Burial, ceremony and settlement near the Graig Lwyd axe factory; palaeo-environmental study at Waun Llanfair, Llanfairfechan, Conwy. Unpublished GAT report no. 662 Davidson, A., Jones, M., Kenney, J., Rees, C., and Roberts, J., 2010. Gwalchmai Booster to Bodffordd link water main and Llangefni to Penmynydd replacement main: Archaeological Mitigation Report. Unpublished GAT report no 885 Hemp, W. J., 1927, The Capel Garmon Chambered Long Cairn, Archaeologia Cambrensis Vol. 82, 1-43, series 7 Hemp, W. J., 1931, ‘The Chambered Cairn of Bryn Celli Ddu’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 216-258 Hemp, W. J., 1935, ‘The Chambered Cairn Known As Bryn yr Hen Bobl near Plas Newydd, Anglesey’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 85, 253-292 Houlder, C. H., 1961. The Excavation of a Neolithic Stone Implement Factory on Mynydd Rhiw, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 27, 108-43 Kenney, J., 2008a. -

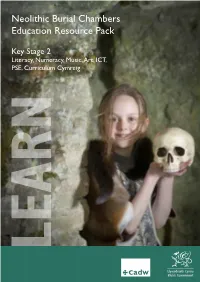

Neolithic Resource

Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Pack Key Stage 2 Literacy, Numeracy, Music, Art, ICT, PSE, Curriculum Cymreig LEARN Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care: Curriculum links: Barclodiad-y-Gawres passage tomb, Anglesey Literacy — oracy, developing & presenting Bodowyr burial chamber, Anglesey information & ideas Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey Numeracy — measuring and data skills Capel Garmon burial chamber, Conwy Music — composing, performing Carreg Coetan Arthur burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Din Dryfol burial chamber, Anglesey Art — skills & range Duffryn Ardudwy burial chamber, Gwynedd Information Communication Technology — Lligwy burial chamber, Anglesey find and analyse information; create & Parc le Breos chambered tomb, Gower communicate information Pentre Ifan burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Personal Social Education — moral & spiritual Presaddfed burial chamber, Anglesey development St Lythans burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan Curriculum Cymreig — visiting historical Tinkinswood burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan sites, using artefacts, making comparisons Trefignath burial chamber, Anglesey between past and present, and developing Ty Newydd burial chamber, Anglesey an understanding of how these have changed over time All the Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care are open sites, and visits do not need to be booked in advance. We would recommend that teachers undertake a planning visit prior to taking groups to a burial chamber, as parking and access are not always straightforward. Young people re-creating their own Neolithic ritual at Tinkinswood chambered tomb, Vale of Glamorgan, South Wales cadw.gov.wales/learning 2 Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource The Neolithic period • In west Wales, portal dolmens and cromlechs The Neolithic period is a time when farming was dominate, which have large stone chambers possibly introduced and when people learned how to grow covered by earth or stone mounds. -

Nash & Stanford, (Nash & Stanford 2007)

ciblées sont nécessaires. En ce qui concerne le tourisme well-directed action is needed. Concerning tourism and et la méthodologie de la recherche, l’Université de Gand research methodology, Ghent University will examine examinera les possibilités de méthodes simples et ren- the possibilities of simple and cost-effective methods tables adaptées aux besoins des populations locales. adapted to the needs of the indigenous population. Remerciements !CKNOWLEDGMENTS Les auteurs tiennent à remercier le soutien financier apporté par The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provi- l’IWT et FWO-Flandres, qui nous ont aidés à organiser nos expéditions ded by IWT and FWO-Flanders, which helped us to organize our expe- et la recherche en laboratoire. Nous tenons également à remercier l’Uni- ditions and the desk-based research. We also wish to thank the Gorno versité d’État Gorno Altaisk pour le travail de terrain commun. Altaisk State University for the joint fieldwork. Gertjan PLETS1, Wouter GHEYLE2 & Jean BOURGEOIS3 1 Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] 2 Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] 3 Head of the Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] BIBLIOGRAPHIE BOURGEOIS I., HOOF L.V., CHEREMISIN D., 1999. — Découverte de pétroglyphes dans les vallées de Sebystei et de Kalanegir (Gorno-Altai). INORA, 22, p. 6-13. CASSEN S., ROBIN G., 2010. — Recording Art on Neolithic Stelae and Passage Tombs from Digital Photographs. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 17, p. 14. CHANDLER J.H., BRYAN P., FRYER J.G., 2007. — The Development and Application of a Simple Methodology for Recording Rock Art Using Consumer-Grade Digital Cameras. -

Origins and Prehistory of Wales: Interpretation Plan

Contents A pan Wales approach to interpreting the prehistoric past Page 1 • Introduction to the Interpretation Plan • Approach to the Plan and its recommendations • Interpretation Plan methodology • Delivering the Interpretation Plan Challenges for interpreting the Origins and Prehistory of Wales Page 5 • Understanding the issues and challenges for interpretation • A simplified chronology • Visual timeline – illustration • Communicating time and key events Audiences for interpretation Page 11 • What we know – current intelligence • The potential • The strategic context • Wales Tourism Strategy • Wales Walking Tourism Strategy • The Wales Spatial Plan • Regional Tourism Strategies • Visit Britain Culture & Heritage Topic Profile • Intelligence for digital audiences and interpretive media • Implications for Origins and Prehistory: target audiences, interpretive media approach Resources (site and collections) and site audits Page 23 • Introduction • Types of sites and monuments • Artefacts • Other resources • Site visits and audits • Emotional auditing • Site response comparisons – emotional audit • Map of sites Developing appealing content and ‘destinations’ Page 29 • Providing context • Strategic approaches to promotion and presentation The Origins and Prehistory of Wales: a strategic approach to interpretation Prepared by Carolyn Lloyd Brown FTS MAHI & David Patrick for Cadw May 2011 Interpretation Framework Page 33 • Interpretive aims • Storyline appeal and interpretive content • A sense of shared ancestry and identity • Interpretive -

An Examination of Regionality in the Iron Age Settlements and Landscape of West Wales

STONES, BONES AND HOMES: An Examination of Regionality in the Iron Age Settlements and Landscape of West Wales Submitted by: Geraldine Louise Mate Student Number 31144980 Submitted on the 3rd of November 2003, in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Arts with Honours Degree School of Social Science, University of Queensland This thesis represents original research undertaken for a Bachelor of Arts Honours Degree at the University of Queensland, and was completed during 2003. The interpretations presented in this thesis are my own and do not represent the view of any other individual or group Geraldine Louise Mate ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page i Declaration ii Table of Contents iii List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements x 1. The Iron Age in West Wales 1 1.1 Research Question 1 1.2 Area of Investigation 2 1.3 An Approach to the Iron Age 2 1.4 Rationale of Thesis 5 1.5 Thesis Content and Organisation 6 2. Perspectives on Iron Age Britain 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Perspectives on the Iron Age 7 2.2.1 Progression of Interpretations 8 2.2.2 General Picture of Iron Age Society 11 2.2.3 Iron Age Settlements and Structures, and Their Part in Ritual 13 2.2.4 Pre-existing Landscape 20 2.3 Interpretive Approaches to the Iron Age 20 2.3.1 Landscape 21 2.3.2 Material Culture 27 2.4 Methodology 33 2.4.1 Assessment of Methods Available 33 2.4.2 Methodology Selected 35 2.4.3 Rationale and Underlying Assumptions for the Methodology Chosen 36 2.5 Summary 37 iii 3.