Cultivating Young People's Relationships to a Theatre Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

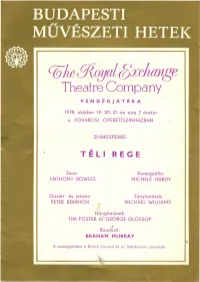

Q;;Heg{Qyalgxchange

q;;he g{qyalgxchange Theatre Company VENDÉGJÁTÉKA 1978. október 19, 20, 21-én este 7 órakor a FŐVÁROSIOPERETTSZíNHÁZBAN SHAKESPEARE: , TELI REGE Zene: Koreográfia: ANTHONY BOWLES MICHELE HARDY Díszlet- és jelmez: Fényhatások: PETER B'ENNION MICHAEL WILLIAMS Hanghatások: TIM FOSTER és GEORGE GLOSSOP ,. Rendező: BRAHAM MURRAY A vendégjátékot a British Council és az Interkoncert szervezte. Szereplők Leontes, Szicília királya James Maxwell MamiIlius, a fia ... Sarah Webb CamilIo Jeffrey Wickham Antigonus Morris Perry szicíliai nemesurak Cliomenes, Peter Guinness Dion Paul Clayton Polixenes, Bohémia királya John Turner Florizel, a fia Richard Durden Archidamus, bohémiai nemesúr Peter Guinness Greg pásztor, akit Perdita atyjának vélnek Harold Goodwin I I Bangó, a fia ... lan Hastings • Autolycus, csavargó Harry Landis Hajós ... Keith Taylor Tömlöcőr Keith Taylor Hermione, Leontes felesége Helen Ryan Perdita, Leontes és Hermione lánya Jacqueline Tong Paulina, Antigonus felesége ... .. Dilys Hamlett Emilia, Hermione udvarhölgye Angela Rooks Philippa Howell Mopsa, Dorcas parasztlányok Chloe Sciennon Knight Moritell, Keith Taylor. Főurak, nemesurak, hölgyek, tisztek, Nicolas Gecks, Peter Guiness szolgák, pásztorok és pásztorlányok Jon Glentoran Történik részint Szicíliában, részínt Bohémiában. , THE ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE COMPANY MANCHESTER A színház jelenlegi társulatának "őse" az az együttes, amely 1959-ben a lan- da ni Lyric Theatre-ben több darabot mutatott be és olyan rendezőkkel, terve- zőkkel és színészekkel büszkélkedett, akik Michel Sein-Denis keze alatt nőttek művésszé és tanultak az Old Vic lsl.olójóbc n. Mindenféle anyagi támogatás nélkül izgalmas előadásokat tudtak teremteni, elsősorban európai drámaírók műveiből, mint Büchner vagy Strindberg. A rnúsornok már csak azért is ~ikere volt, mert Angliában abban az időben nemigen nyúltak az európai klcssziku- sokhoz. A színészeket is igen nagyra értékelte a kritika, többek között Patrick Wym<,rkot, Mai Zetterlinget és Rupert Daviest. -

Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Haworth Tompkins

Conservation Management Plan For The National Theatre Final Draft December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Final Draft - December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Ltd 19-20 Great Sutton Street London EC1V 0DR Front Cover: Haworth Tompkins Ltd 2008 Theatre Square entrance, winter - HTL 2008 Foreword When, in December 2007, Time Out magazine celebrated the National Theatre as one of the seven wonders of London, a significant moment in the rising popularity of the building had occurred. Over the decades since its opening in 1976, Denys Lasdun’s building, listed Grade II* in 1994. has come to be seen as a London landmark, and a favourite of theatre-goers. The building has served the NT company well. The innovations of its founders and architect – the ampleness of the foyers, the idea that theatre doesn’t start or finish with the rise and fall of the curtain – have been triumphantly borne out. With its Southbank neighbours to the west of Waterloo Bridge, the NT was an early inhabitant of an area that, thirty years later, has become one of the world’s major cultural quarters. The river walk from the Eye to the Design Museum now teems with life - and, as they pass the National, we do our best to encourage them in. The Travelex £10 seasons and now Sunday opening bear out the theatre’s 1976 slogan, “The New National Theatre is Yours”. Greatly helped by the Arts Council, the NT has looked after the building, with a major refurbishment in the nineties, and a yearly spend of some £2million on fabric, infrastructure and equipment. -

Press Release Th 18 Sept 2013

Press Release th 18 Sept 2013 Full programme announced today for first ever UK-wide Family Arts Festival 500 UK venues and organisations to host over 1,000 music, theatre, dance, circus and visual arts events to attract family audiences to the arts this autumn. New festival aims to build on the momentum of the London 2012 Festival and Cultural Olympiad. Over 25% of the festival’s events will be free, with many more events less than £10 and lots of special offers, including reduced-price and family tickets. www.familyartsfestival.com The full programme for the Family Arts Festival was announced today at a special preview event at Shakespeare’s Globe in London. The Family Arts Festival will launch one month today, running 18th October – 3rd November 2013 and aiming to build on the momentum of the London 2012 Festival and Cultural Olympiad. [Click here to download images of a dramatic unveiling of Globe Education’s Muse of Fire, which will premiere at the Family Arts Festival from 28th October.] The first ever UK-wide Family Arts Festival will see over 500 organisations host over 1,000 family friendly arts events. From an operatic version of The Importance of Being Earnest in Derry / Londonderry, Northern Ireland, to Out of The Shadows, a dance and acrobatic extravaganza in Cardiff, Wales, West End favourite Stomp in Cornwall, life drawing with sheep at the Royal Academy, London, and a world premiere of Dragon, a Scottish / Chinese co-production in Inverness, Scotland, the whole of the UK will be alive with arts activities that will appeal to a wide range of families. -

Bel News V2 1/9/05 10:44 Page 2

bel news V2 1/9/05 10:44 Page 2 belgradeplazanews coventry issue one Welcome to Belgrade Plaza News - with so much going on at Belgrade Plaza we have decided that timetable we would like residents and businesses in the city Temporary car park on former “ to be kept informed of our progress Coronet House open on site through a newsletter. August 05 Archaeological Dig ” Completion Autumn 05 Closure of Leigh Mills Car Park Autumn 05 Work start - Leigh Mills Car Park Autumn 05 Completion of Leigh Mills Car Park Summer 06 Phase II Courtyard site apartments and two bars start on site Plans for a new development on the site of The existing Leigh Mills Car Park will be Summer 06 the former Bond Street Car Park were first significantly extended and improved to provide discussed several years ago. almost 1,100 spaces, together with a new With the redevelopment of the Belgrade Theatre, management office, service Phase III main block it was seen as the perfect time to create an core and improved security features. Casino, two hotels further bars and exciting new residential, retail and leisure quarter Belgrade Plaza has been planned to form an restaurants and remainder of to act as a gateway to the city centre. attractive leisure quarter and a vibrant gateway residential start on site That is when our two companies - the Deeley to the city centre to complement the multi-million Group and Oakmoor Estates - joined together pound improvements to the Belgrade Theatre Autumn 06 as Oakmoor Deeley to put forward ideas for and link the site to the Precinct. -

Restaurant Opportunities

1 RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES Available Q1 2019 This is an exclusive opportunity to be part of something special in Coventry City Centre. AWARD WINNING DEVELOPER 2 EVOLVING Coventry CV1 The City of Coventry has a population Belgrade Theatre, Belgrade Plaza of over 316,000 people, making it the 9th largest city in England and the 12th largest city in the UK. Selected to be the UK’s City of Culture for 2021, Coventry is immensely proud of its history, innovation and creativity. The city is home to successful education, business, sport and a thriving arts and cultural sector, offering engaging entertainment locally, by day and night; from street performances to shopfront theatre, to professional shows and events. Cocktails and dinner reservations Credit: Robert Day 3 The city of Coventry has reinvented itself as one of the UK’s top performing regional cities. Investment Coventry has been named the UK’s City of Culture for 2021, giving it a one-off opportunity to boost the economy, tourism, civic pride and access to the arts. Coventry is undergoing a £9 billion programme of investment with potential to create over 70,000 new jobs. IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD industry Coventry is home to many internationally renowned businesses including Barclays, E.on, Located at the heart of Coventry’s cultural and leisure district, The Co-Operative Ericsson, Jaguar Land Rover, LEVC, Sainsbury’s, Severn Trent and Tui. The British motor building sits opposite Belgrade Theatre, industry was born in Coventry, providing 10% of the UK’s automotive jobs. St John the Baptist Church and a stone’s throw from Spon Street, Coventry growth University and Skydome. -

Covcc Letter To:REQ00624 Response

Information Governance C West Executive Director Council House Earl Street Coventry CV1 5RR Please contact Information Governance 25 November 2015 Direct line 024 7683 3323 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Request ID: REQ00624 Thank you for your request for information relating to societies that are licensed to promote lotteries. Please find attached spreadsheet in response to your request. The supply of information in response to a freedom of information request does not confer an automatic right to re-use the information. You can use any information supplied for the purposes of private study and non-commercial research without requiring further permission. Similarly, information supplied can also be re-used for the purposes of news reporting. An exception to this is photographs. Please contact us if you wish to use the information for any other purpose. Should you wish to make any further requests for information, you may find what you are looking for is already published on the Council’s web site and in particular its FOI/EIR Disclosure log, Council's Publication Scheme, Open Data and Facts about Coventry. Yours faithfully Business Support Officer Place Directorate Enclosure: REQ00624 Copy of lotteries 2 Licence Address Source Name Source Address Source Phone Number Camping and Caravanning Club, Greenfields Robert Louden, Greenfields House, Westwood Way, Coventry, CV4 House, Westwood Way, Coventry, CV4 8JH Mr Robert Louden 8JH N/A Potters Green Primary School, Ringwood Highway, Coventry, -

Written and Directed by Jeremy Podeswa Produced by Robert Lantos Based Upon the Novel by Anne Michaels Runtime: 105 Minutes to D

Written and Directed by Jeremy Podeswa Produced by Robert Lantos Based upon the novel by Anne Michaels Media Contacts: New York Agency: Los Angeles Agency: IDP/Samuel Goldwyn Films Donna Daniels Lisa Danna New York: Amy Johnson Melody Korenbrot Liza Burnett Fefferman Donna Daniels PR Block-Korenbrot, Inc. Jeff Griffith-Perham 20 West 22nd St., Suite 1410 North Market Building Samuel Goldwyn Films New York, NY 1010 110 S. Fairfax Ave., #310 1133 Broadway – Suite 926 T: 347.254.7054 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10010 [email protected] T: 323.634.7001 T: 212.367.9435 [email protected] [email protected] F: 212.367.0853 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LA: Mimi Guethe T: 310.860.3100 F: 310.860.3198 [email protected] Runtime: 105 minutes To download press notes and photography, please visit: www.press.samuelgoldwynfilms.com USER NAME: press LOG IN: golden! 1 FUGITIVE PIECES THE CAST Jakob Stephen Dillane Athos Rade Sherbedgia Alex Rosamund Pike Michaela Ayelet Zurer Jakob (young) Robbie Kay Ben Ed Stoppard Naomi Rachelle Lefevre Bella Nina Dobrev Mrs. Serenou Themis Bazaka Jozef Diego Matamoros Sara Sarah Orenstein Irena Larissa Laskin Maurice Daniel Kash Ioannis Yorgos Karamichos Allegra Danae Skiadi 2 FUGITIVE PIECES ABOUT THE STORY A powerful and unforgettably lyrical film about love, loss and redemption, FUGITIVE PIECES tells the story of Jakob Beer, a man whose life is transformed by his childhood experiences during WWII. The film is based on the beloved and best-selling novel by Canadian poet Anne Michaels. -

Maga Magazinović and Modern Dance in Serbia (1910-1968): Marking the Fiftieth Anniversary of Her Death

NADEŽDA MOSUSOVA (Belgrade / Serbia) Maga Magazinović and Modern Dance in Serbia (1910-1968): Marking the Fiftieth Anniversary of her Death Introduction This report about the highly intelligent and multifaceted Serbian personality, Maga Magazinovi!, is based mainly on her memoirs, which were written in 1951-1960 and deal with the period of her life from childhood until 1927. 1 Maria/Magdalena Magazinovi! (1882 -1968), called Maga, came from a modest provincial family in the then Kingdom of Serbia, completing her stu- dies at Belgrade University in 1904. Maga’s subjects were philosophy and German language and literature. She worked first as a librarian at the Natio- nal Library, then as a teacher at the Girls’ High School (gymnasium) in Bel - grade. She was a good translator and the first Serbian female journalist (columnist), with a socialist and feminist engagement. Her dynamic presence was soon noticed by intellectuals in the Serbian capital for its wits and talents, for example Maga’s predilection for dance. Dance in general (except ballroom and folk) and ballet were unknown in Serbia during the first decade of the twentieth century. Opera was at its very beginning, and thus there was only a tradition in drama, practiced in the National Theatre of Belgrade, which was founded in 1868. Salome in Belgrade The National Theatre, this very important centre of cultural life in Serbia, hosted the guest presentation of Maud Allan in 1907, with her interpretation of the dancing piece Salome , supported by music of Marcel Remy. Traditio- nally, patriarchal Serbian society accepted with approval (mainly the female part) the barefoot appearance of this well known Canadian dancer. -

COVENTRY MYSTERY PLAYS – Material Held at Coventry History Centre

COVENTRY MYSTERY PLAYS – Material Held at Coventry History Centre CCA/3/1/14631 File relating to Coventry Cathedral Festival 1957 - 1962 General correspondence relating to the preparations for the Coventry Cathedral Festival of 1962, which commemorated the consecration of the new Cathedral. The letters and memos etc. collected here are concerned mostly with the provision of temporary car parking facilities during the Festival, the provision of first aid stations, street decorations, temporary youth hostels for visiting youngsters, the Festival programme (along with numbers in attendance, numbers of performers), and the presentation in Shelton Square of a Mystery Play by the Coventry Guild Players. CCH/1/11/26 File relating to the Coventry Mystery Plays production in 2003 Jun 2002 - Sep 2003 Papers relating particularly to talks and exhibition at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, including flyer CCH/1/11/27/1-2 File relating to the Coventry Mystery Plays production in 2006 Oct 2005 - Aug 2006 Papers relating particularly to talks and exhibition at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum. Includes /2 copy of the script for the Play by Ron Hutchins CCH/1/27/13 File relating to the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry Jul 2002 - Dec 2000 Miscellaneous papers including some Board papers, capital development scheme presentation, July 2003, correspondence etc relating to the production of the 'Mystery Play' in 2003 CCH/1/27/128 File relating to talk by Pamela King at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in connection with production of the Mystery Plays in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral Jul 2006 - Oct 2006 PA2287/23/21/1-10 'Our Millennium Photographs' 2000 Sheets of photographs including the opening ceremony of the new school, children from year 6 on an adventure holiday at Dol-y-moch, Wales, children wearing Easter bonnets and a scene from the mystery play PA2313: BELGRADE THEATRE COLLECTION PA2313/1/2/22/3 Programme: Coventry Mystery Plays 1 Aug 1978 - 12 Aug 1978 [Belgrade Theatre] Performed in the Cathedral Ruins. -

Download Publication

' o2G1,t c V L Co P Y The Arts Council of Twenty fifth Great Britain annual report and accounts year ended 31 March 1970 ARTS COUNCIL Of GREAT BRITAIN I REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE FROM THE IIBRI► Membership of th e ' council, committees and panels Council Professor T. J. Morgan, DLitt The Lord Goodman (Chairman) Henry Nyma n Sir John Witt (Vice-Chairman) Dr Alun Oldfield-Davies, CB E The Hon Michael Astor Miss Sian Phillip s Richard Attenborough, CB E T. M. Haydn Rees Frederic R . Cox, OBE Gareth Thomas ' Colonel William Crawshay, DSO, TD Miss D. E. Ward Miss Constance Cumming s Tudur Watkins, MB E Cedric Thorpe Davie, OBE, LLD Clifford William s Lady Antonia Fraser Mrs Elsie M. Williams, iP Professor Lawrence Gowing, CBE Peter Hall, CBE The Earl of Harewoo d Art Panel Hugh Jenkins, MP John Pope-Hennessy, CBE (Chairman) Professor Frank Kermod e Professor Lawrence Gowing, CBE (Deputy Chairman ) J. W. Lambert, CBE, DS C Ronald Alle y Sir Joseph Lockwoo d Alan Bowness Dr Alun Oldfield-Davies, CB E John Bradshaw John Pope-Hennessy, CBE Michael Brick Lewis Robertson, CBE Professor Christopher Cornford George Singleton, CB E Theo Crosby Robyn Denny The Marquess of Dufferin and Av a ' Scottish Arts Council Francis Hawcroft Lewis Robertson, CBE (Chairman) Adrian Heath George Singleton, CBE (Vice-Chairman) Edward Lucie-Smith Neill Aitke n Miss Julia Trevelyan Oman, DeSRCA, MSI A J. S. Boyle P. S. Rawson Colin Chandler Sir Norman Reid ' Stewart Conn Bryan Robertson, OB E Cedric Thorpe Davie, OBE, LL D Sir Robert Sainsbury David A. -

David Horovitch

David Horovitch FILM Rebecca Coroner Working Title Ben Wheatley Summerland Albert Shoebox Films Jessica Swale The Nun Cardinal Conroy New Line Corin Hardy Marrowbone Redmond Tele5 Sergio G Sanchez HHHH Admiral Hansen Adama Pictures Cedric Jimenez The Sense of an Ending Headmaster BBC Films Ritesh Batra The Chamber The Captain Chamber Films Ben Parker The Infiltrator Saul Mineroff Good Films Ltd Brad Fuman Mr. Turner Dr. Price Film 4 Mike Leigh Blink (Short) Harry Starfish Films Paul Wilkins Young Victoria Sir James Clark Initial Entertainment Group Jean Marc Vallee Veiled Michael Dan Susman In Your Dreams Edward Shoreline Entertainment Gary Sinyor WASP 06 Pop Jelly Roll Prods Woody Allen 102 Dalmations Doctor Pavlov Walt Disney Kevin Lima Max MaxÍs Father Pathú Menno Meyjes One of the Hollywood Ten Ben Margolis Bloom Street Prods Karl Francis Soloman and Gaenor Isaac APT Film & Television Paul Morrison Paper Marriage Frank Haddow Mark Forstater Krzysztof Lang Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission Pierre Claudel MGM Lee H. Katzin An Unsuitable Job for a Woman Sergeant Maskell Castle Hill Prods Inc. Christopher Petit TELEVISION Dad's Army Colonel Square UKTV Various Untitled NPX Project Judge Raptor Pictures LTD Various Directors Doctors 2018 Harry Brook BBC Various Churchill's Secret Affairs Jock Colville Channel 4 Holby City Rabbi Stein BBC Various Doctors Gerald Dunlop BBC Various The Assets US Ambassador ABC Jeff T.Thomas/ Rudy Bednar/ Adam Feinstein Casualty Morris BBC Paul Murphy Heartbeat Douglas ITV Roger Bamford Trial & Retribution Alistair Darwin ITV Ben Ross Casualty 1907 Lord Rothchild BBC Bryn Higgins Donovan Palmer Thornhill Granada Ciaran Donnelly Dirty War Lambert BBC Daniel Percival Goodbye Mr. -

Harriet Walter

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Harriet Walter Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square Elizabeth Fieldhouse London, W1F 9JL, [email protected] United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company Caroline, Countess of Carnival Film & BELGRAVIA John Alexander Brockenhurst Television/Epix/ITV Jessica M. Thompson/Jonathan THE END Edie Henley See Saw Films/Sky Atlantic Brough THE SPANISH PRINCESS Margaret Beaufort Birgitte Stærmose All3 Media/Starz SUCCESSION Series 1 & 2 Nominated for the Best Guest Actress in a Drama Series Award, Lady Caroline Collingwood Various HBO Primetime Emmy Awards, 2020 PATRICK MELROSE Princess Margaret Edward Berger Showtime/Sky Atlantic BLACK EARTH RISING Eve Ashby Hugo Blick BBC/Netflix FLOWERS Hylda Will Sharpe Kudos/Channel 4 CALL THE MIDWIFE Sister Ursula Various BBC BLACK SAILS Marilyn Guthrie Robert Levine Starz THE CROWN Clementine Churchill Stephen Daldry Netflix LONDON SPY Claire Jakob Vebruggen BBC THE ASSETS Jeanne Vertefeuille Various ABC DOWNTON ABBEY Lady Shackleton Various Carnival LAW AND ORDER: UK Natalie Chandler Various Kudos BY ANY MEANS Sally Walker Menhaj Huda Red Planet Productions HEADING OUT Angela Natalie Bailey Red Production Company Oxford Film & Television/BBC SIMON SCHAMA'S SHAKESPEARE Actress Ashley Gething Worldwide THIS SEPTEMBER Isobel Balmerino Giles Foster Gate Television HUNTER ACC Jenny Griffin Colm McCarthy BBC A SHORT STAY IN SWITZERLAND Clare Simon Curtis BBC LITTLE DORRIT Mrs. Gowan Dearbhla Walsh/Adam Smith BBC AGATHA CHRISTIE'S POIROT: CAT AMONGST THE Mrs Bulstrode James Kent ITV PIGEONS 10 DAYS TO WAR Anne Campbell David Belton BBC BALLET SHOES Dr.