Burn It Down: the Incommensurability of the University and Decolonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism Vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise

Domestic Colonies and Colonialism vs Imperialism in Western Political Thought and Practise Over the last thirty years, there has been a rapidly expanding literature on colonialism and imperialism in the canon of modern western political thought including research done by James Tully, Glen Coulthard, David Armitage, Karuna Mantena, Duncan Bell, Jennifer Pitts, Inder Marwah, Uday Mehta and myself. In various ways, it has been argued the defense of colonization and/or imperialism is embedded within and instrumental to key modern western, particularly liberal, political theories. In this paper, I provide a new way to approach this question based on a largely overlooked historical reality - ‘domestic’ colonies. Using a domestic lens to re-examine colonialism, I demonstrate it is not only possible but necessary to distinguish colonialism from imperialism. While it is popular to see them as indistinguishable in most post-colonial scholarship, I will argue the existence of domestic colonies and their justifications require us to rethink not only the scope and meaning of colonies and colonialism but how they differ from empires and imperialism. Domestic colonies (proposed and/or created from the middle of the 19th century to the start of the 20th century) were rural entities inside the borders of one’s own state (as opposed to overseas) within which certain kinds of fellow citizens (as opposed to foreigners) were segregated and engaged in agrarian labour to ‘improve’ them and the ‘uncultivated’ land upon which they laboured. Three kinds of domestic colonies were proposed based upon the population within them: labour or home colonies for the ‘idle poor’ (vagrants, unemployed, beggars), farm 1 colonies for the ‘irrational’ (mentally ill, disabled, epileptic) and utopian colonies for political, religious and/or racial minorities. -

The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: the Case of Palestine

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM PhD THESIS NICOSIA 2019 WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM NEAREAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM PhD THESIS THESIS SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. UMUT KOLDAŞ NICOSIA 2019 ACCEPTANCE/APPROVAL We as the jury members certify that the PhD Thesis ‘Who is Eligible to Exist? The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: The Case of Palestine’prepared by PhD Student Waleed Hasan Salem, defended on 26/4/2019 4 has been found satisfactory for the award of degree of Phd JURY MEMBERS ......................................................... Assoc. Prof. Dr. Umut Koldaş (Supervisor) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Sait Ak şit(Head of Jury) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Nur Köprülü Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of Political Science ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Ali Dayıoğlu European University of Lefke -

Land of Abundance: a History of Settler Colonialism in Southern California

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Benjamin Shultz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shultz, Benjamin, "LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA" (2020). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 985. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 Approved by: Thomas Long, Committee Chair, History Teresa Velasquez, Committee Member, Anthropology Michal Kohout, Committee Member, Geography © 2020 Benjamin O Shultz ABSTRACT The historical narrative produced by settler colonialism has significantly impacted relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions. This thesis focuses on the enduring narrative of settler colonialism and its connection to American Civilization. -

The Novel Cassard Le Berbère, Published in 1921 by Robert Randau

History, Literature, and Settler Colonialism in North Africa Mohamed-Salah Omri he novel Cassard le Berbère, published in 1921 by Robert Randau T(1873–1950), a key fi gure in the Francophone culture of Algeria, tells the story of a settler named Cassard-colon who traces his ancestry to a pirate, Cassard-corsaire. The family of Cassard-corsaire settled in the mountains of Provence during the Islamic invasion of the region. Cassard-colon returns to North Africa and barricades himself in Borj Rais, formerly a Byzantine castle built on the remains of a Roman villa, which in turn stood atop a Punic necropolis. The invention and staging of a historical memory for the homecoming of Cassard-colon may be spectacular, but there is nothing fantastic about their implications. In fact, neither Cassard-colon’s ancestry nor his fortress, given Mediterra- nean cultural and historical contexts, is totally implausible.1 Randau’s An earlier version of this essay was presented at the Fourth Mediterranean Social and Political Research Meeting, Florence and Montecatini Terme, Italy, March 19–23, 2003; the meeting was organized by the Mediterranean Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute. I would like to thank the participants in the workshop “The Mediterranean: A Sea That Unites/A Sea That Divides” for their remarks, Florence Martin for commenting on earlier versions of the essay, and Nisrine Omri for her thoughtful editing. The essay is dedicated to Fatin from the occupied Palestinian West Bank, for her story and the story of her people run beneath and through this one. -

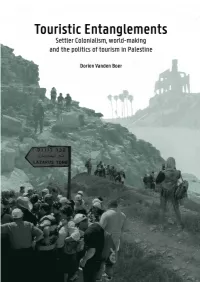

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

The Settler-Colonial Mythology Of

“GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 by Dustin Michael Naegle Bachelor of Science, 2004 Utah State University Logan, UT Master of Theological Studies, 2007 Brite Divinity School Fort Worth, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, TX April 2017 “GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE Claudia V. Camp Thesis Director David M. Gunn Reader Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joretta Marshall Dean For Dad (1958–1985) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of people to whom I am indebted for the completion of this project exceeds far beyond what space allows. I am particularly thankful to my director and mentor Claudia V. Camp, who taught me what good scholarship is by challenging me intellectually and fostering my research interests. I am particularly thankful for the countless hours she devoted to reviewing and commenting on my work. Her guidance and support has profoundly influenced me as a scholar and as a human being. I am honored to have been her student. I am also thankful to David M. Gunn for his willingness to serve as a reader for this project. His insight and support proved to be invaluable. I also wish to thank Lorenzo Veracini, Patricia Lorcin, and Tamara Eskenazi who all provided helpful feedback. I would also like to thank the many teachers who helped shape my understanding of the world, particularly Warren Carter, Toni Craven, Steve Sprinkle, and Elaine Robinson. -

Settler Colonialism As Structure

SREXXX10.1177/2332649214560440Sociology of Race and EthnicityGlenn 560440research-article2014 Current (and Future) Theoretical Debates in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2015, Vol. 1(1) 54 –74 Settler Colonialism as © American Sociological Association 2014 DOI: 10.1177/2332649214560440 Structure: A Framework for sre.sagepub.com Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation Evelyn Nakano Glenn1 Abstract Understanding settler colonialism as an ongoing structure rather than a past historical event serves as the basis for an historically grounded and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender formation. The settler goal of seizing and establishing property rights over land and resources required the removal of indigenes, which was accomplished by various forms of direct and indirect violence, including militarized genocide. Settlers sought to control space, resources, and people not only by occupying land but also by establishing an exclusionary private property regime and coercive labor systems, including chattel slavery to work the land, extract resources, and build infrastructure. I examine the various ways in which the development of a white settler U.S. state and political economy shaped the race and gender formation of whites, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Chinese Americans. Keywords settler colonialism, decolonization, race, gender, genocide, white supremacy In this article I argue for the necessity of a settler to fight racial injustice. Equally, I wish to avoid colonialism framework for an historically grounded seeing racisms affecting various groups as com- and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender for- pletely separate and unrelated. Rather, I endeavor mation. A settler colonialism framework can to uncover some of the articulations among differ- encompass the specificities of racisms and sexisms ent racisms that would suggest more effective affecting different racialized groups—especially bases for cross-group alliances. -

Philistine Influence on Israelite Ethnic Identity

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Pitkänen, Pekka M A ORCID: 0000-0003-0021-7579 (2015) Ancient Israel and Philistia: Settler Colonialism and Ethnocultural Interaction. Ugarit Forschungen, 45. pp. 233- 263. Official URL: https://www.ugarit-verlag.com/ EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/2887 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Pitkänen, Pekka M A (2015). Ancient Israel and Philistia: Settler Colonialism and Ethnocultural Interaction. Ugarit Forschungen, 45 233-263. ISSN 978-3-86835-137-8 Published in Ugarit Forschungen, and available online at: https://www.ugarit-verlag.com/ We recommend you cite the published (post-print) version. The URL for the published version is https://www.ugarit-verlag.com/ Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. -

Unsettling Settler Colonialism: the Discourse and Politics of Settlers, and Solidarity with Indigenous Nations

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 3, No. 2, 2014, pp. 1-32 Unsettling settler colonialism: The discourse and politics of settlers, and solidarity with Indigenous nations Corey Snelgrove University of British Columbia Rita Kaur Dhamoon University of Victoria Jeff Corntassel University of Victoria Abstract Our goal in this article is to intervene and disrupt current contentious debates regarding the predominant lines of inquiry bourgeoning in settler colonial studies, the use of ‘settler’, and the politics of building solidarities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Settler colonial studies, ‘settler’, and solidarity, then, operate as the central themes of this paper. While somewhat jarring, our assessment of the debates is interspersed with our discussions in their original form, as we seek to explore possible lines of solidarity, accountability, and relationality to one another and to decolonization struggles both locally and globally. Our overall conclusion is that without centering Indigenous peoples’ articulations, without deploying a relational approach to settler colonial power, and without paying attention to the conditions and contingency of settler colonialism, studies of settler colonialism and practices of solidarity run the risk of reifying (and possibly replicating) settler colonial as well as other modes of domination. Keywords: settler colonial studies; solidarity; Indigenous resurgence; place-based solidarity 2014 C. Snelgrove, R. Dhamoon & J. Corntassel This is an Open Access article distributed -

Settler Colonialism, Water Inequality, and Rural Injustice in the US Southwest

ABSTRACT BRAY, LAURA ANN. Dividing the San Juan: Settler Colonialism, Water Inequality, and Rural Injustice in the US Southwest. (Under the direction of Dr. Thomas E. Shriver). Rural communities of color suffer multiple forms of water injustice that result in insecure and unsafe water supplies, including contaminated drinking water and inadequate water infrastruc- ture. Native nations face the additional challenge of protecting their legal water rights against con- stant threats from non-Native communities and governments. This dissertation draws on theories of critical environmental justice (Pellow 2018) to examine the formation or rural water inequality in Indigenous communities. Two primary lines of research within this literature inform this study: rural environmental justice (Mckinney 2016; Pellow 2016a) and settler colonialism (Bacon 2019; Whyte 2018). I merge insights from these frameworks to examine intersections of race, space, and Indigeneity within processes of environmental inequality formation. Drawing on archival and historical sources, this study takes a historical case study approach to explore: (1) racial projects within rural environmental inequality formation, (2) the construction and mobilization of socio-spatial boundaries within natural resource conflicts, and (3) state bu- reaucratic mechanisms used to enact settler colonial projects. The case study focuses on two closely related federal water projects that divided San Juan River waters in New Mexico between the rural Navajo Nation and the rapidly urbanizing Middle Rio Grande Valley. Authorized in 1962, the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project (NIIP) was designed to alleviate widespread poverty on the Navajo Nation by developing an agricultural industry. At the same time, Congress approved the San Juan-Chama Project (SJCP) to divert water from the San Juan River to the Rio Grande River Basin, primarily for use in Albuquerque. -

Self-Determination, Sovereignty, and History: Situating Zionism in the Settler Colonial Archive

SELF-DETERMINATION, SOVEREIGNTY, AND HISTORY: SITUATING ZIONISM IN THE SETTLER COLONIAL ARCHIVE 0 SELF-DETERMINATION, SOVEREIGNTY, AND HISTORY: SITUATING ZIONISM IN THE SETTLER COLONIAL ARCHIVE Stephen James Nutt Submitted to the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arab and Islamic Studies September 2018 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotations from the thesis may be published without the proper acknowledgment. I certify that all materials in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university -------------------------- 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisory team, Professor Ilan Pappé, whose work has been a personal and intellectual inspiration to me since long before I embarked upon this project, and Professor William Gallois whose wide interests and breadth of reading has always ensured an unexpected perspective on my work. Collectively they have provided me with the positive support in my ideas to follow the strength of my convictions in my research, something that does not come naturally to me, for which I cannot thank them enough. I would like to extend particular thanks to, Salim Abuthaher, Qasam Al-Haj, Abdul Jawad Hamayel, Fairouz Salem, Yaser Shalabi, Mawakib Massad, Lisa Taraki, and Halla Shoabi for arraigning and funding my visit to Birzeit University, where I was able to present parts of this project and participate in the University’s first international Graduate Conference.