Afterword: in Search of Melanesian Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science, Religion, and Fundamentalism John Hooker Osher Course April 2013 Science and Religion

Science, Religion, and Fundamentalism John Hooker Osher Course April 2013 Science and Religion • Science makes the world explicable and predictable. • This is one of the functions of religion. • There is every reason for science to be part of religion. Science and Religion • Science makes the world explicable and predictable. • This is one of the functions of religion. • There is every reason for science to be part of religion. • Historically, it has been (until mid-19th c). • We have reinvented this history. Science and Religion • There has been dispute over interpretation of scripture. • But this is not due to science. • It is a perennial phenomenon. Science and Religion • Pythagoras (570-495 bce) • First theorem in world history. • Beginning of Western mathematics. • Reassurance that humans have immortal souls. Science and Religion • Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) • Saw the universe as reflecting the glory of the Creator. • Believed that Aristotelian cosmology did not do it justice. • His heliocentric system reflected “the movements of the world machine, created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all.” • The Pope and several Catholic bishops urged him to publish his ideas. Science and Religion • Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) • Insisted that science harmonize with theology. • Rejected Copernican view partly on Biblical grounds. Science and Religion • Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) • Church was interested in science. • Pope encouraged Galileo’s research, but Galileo insulted him in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Science and Religion • Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) • Devout Lutheran, saw evidence of the Trinity in the heavens. • His laws of planetary motion are inspired by desire to find divine order in the universe. -

Arthur Grimes**

Monetary Policy and Economic Imbalances: An Ethnographic Examination of the Arbee Rituals* Arthur Grimes** Introduction In his “Life Among the Econ” Axel Leijonhufvud (1973) took an ethnographic approach to describing the Econ tribe and, especially, two of its components: the Macro and the Micro. My purpose is to delve further into the life of the Macro, specifically examining the Arbee sub-tribe. Like Leijonhufvud, I take an ethnographic approach, having lived amongst the Arbee for two lengthy periods totalling twenty-four years. The Arbee sub-tribe that I have lived within, and will examine here, is situated in a small set of islands in the southern Pacific Ocean, that some call Aotearoa and others call New Zealand. They are related to Arbee sub-tribes elsewhere in the world through tight kinship connections.1 In ethnographic research,2 it is common to collect data through direct, first-hand observation of participants’ activities. Interviews may be used, varying from formal interviews to frequent casual small talk. Suffice to say, that no formal interviews have been adopted for this research. However there has been much first hand observation both of the Arbee people and of their relationships with other tribes and sub-tribes both in Aotearoa and beyond. The Imbalance The task of our research is to examine the nature of the Arbee reaction to claims by other tribes and sub-tribes that the Arbee rituals have caused The Imbalance in The Economy.3 Specifically, their highly formalised OC Ritual (OCR) has been blamed for creating The * I wish to thank Professor David Bettison who, in teaching me economic anthropology, taught me more about the subject of economics than did any economist before or since. -

Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1972 Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea Paul Finnane Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Finnane, Paul, "Prophet -- a Symbol of Protest a Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults in Papua New Guinea" (1972). Master's Theses. 2615. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1972 Paul Finnane THE PROPHET--A SYifJ30L OF PROTEST A Study of the Leaders of Cargo Cults · in Papua New Guinea by Paul Finnane OFM A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University, Chicago, in Partial Fulfillment of the-Requirements for the Degree of r.;aster of Arts June 1972 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .• I wish to thank Sister I·llark Orgon OSF, Philippines, at whose urging thip study was undertaken: Rev, Francis x. Grollig SJ, Chair~an of the Department of Anthropology at Loyola University, Chicago, and the other members of the Faculty, especially Vargaret Hardin Friedrich, my thesis • ""' ..... d .. ·+· . super\!'isor.. '\¥ •• ose sugges --ion=? an pcrnpicaciouo cr~.. w1c1sm helped me through several difficult parts o~ the. -

Los Angeles Harbor College Anthropology 121 Spring 2016 the Anthropology of Magic, Religion and Witchcraft Dr

Los Angeles Harbor College Anthropology 121 Spring 2016 The Anthropology of Magic, Religion and Witchcraft Dr. Sasha David [email protected] Section 0109: Tuesdays and Thursdays 9:35 - 11 AM Office Hours: Monday – Thursday 1 – 3 PM Office Phone and Location: (310) 233-4577; NEA 157 Course Description: This course considers the origins and varieties of religious beliefs and practices cross-culturally. Topics include mythology, symbolism, shamanism, altered states of consciousness, magic, divination, witchcraft, and the question of cults. Los Angeles Harbor College Mission Statement: Los Angeles Harbor College promotes access and student success through associate and transfer degrees, certificates, economic and workforce development, and basic skills instruction. Our educational programs and support services meet the needs of diverse communities as measured by campus institutional learning outcomes. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. Using a culturally relativistic and ethnographic framework, students should recognize a variety of religious experiences. 2. Define the term “culture” and explain how it impacts the lives of individuals. 3. Compare the different ways the term religion is defined and distinguish different anthropological approaches to the study of religion. 4. Identify and discuss the functions served by various religious phenomena, both for the individual and society. 5. Explain how religious phenomena, such as the nature of supernatural beings and witchcraft beliefs, reflect the culture in which they are found. 6. Identify and apply the basic concepts of the class, including mythology, symbolism, rituals, specialists, altered states, magic, divination, supernatural beings, and witchcraft. 7. Examine how and why new religious movements arise, and why others decline. 1 | P a g e Assigned readings for the course: Stein, Rebecca and Stein, Philip. -

Magic Gardens in Tanna

I MAGIC GARDENS IN TANNA Joël Bonnemaison ORSTOM Paris Magical thought is not to be regarded as a beginning, a rudi- ment, a sketch, a part of a whole which has not yet material- ized. It forms a well-articulated system, and is in, this respect independent of that other system which constitutes science. It is therefore better, instead of contrasting magic and sci- ence, to compare them as two parallel modes of acquiring knowledge. Their theoretical and practical results differ in value. Both science and magic, however, require the same sort of mental operations and they differ not so much in kind as in the different types of phenomena to which they are applied. Claude Lévi-Strauss The Savage Mind Tanna, an island in the southern part of the Melanesian archipelago of Vanuatu,l occupies a special place in the ethnological literature of the South Pacific because of its peculiar history. I worked on this island in I an ethnogeographic capacity in 1978 and 1979, staying in villages located in the northwest (Loanatom and Imanaka) and then in the cen- tral part, called Middle Bush (Lamlu). My purpose was to study tradi- tional land tenure through the mapping of customary territories (this research was published in Bonnemaison 1985,1986, 1986-1987). Along the way I discovered the magic gardens of Tanna. In the first two decades of this century it was thought that Christian- * 71 al F P II 1 L t 72 Pacific Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4-December 1991 ization of Tanna was practically complete. “Pagan magic” seemed to have disappeared and “Christian order” reigned over the island, en- forced by a sort .of militia of zealous neophytes anxious to impose by force the new moral concepts of Presbyterian theocracy and monothe- ism (see Guiart 1956; Adams 1984). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE LAMONT LINDSTROM Department of Anthropology University of Tulsa Tulsa, OK 74104 (918) 631-2888; 631-2540 (Fax) [email protected] EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Ph.D 1981 - University of California, Berkeley M.A. 1976 - University of California, Berkeley A.B. 1975 - University of California, Berkeley University of California, Santa Cruz PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: 2/17- Associate Dean, Henry Kendall College of Arts and Sciences, University of Tulsa 8/13 – 6/17 Co-Director, Women’s and Gender Studies Program, U. Tulsa 7/09 - Kendall Professor of Anthropology, University of Tulsa 6/08 – 5/09 President, University of Tulsa Faculty Senate 6/06 – 8/10 Chair, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Tulsa 1/99 - Research Partner, Q2 Consulting Group, LLC 1/99 - 5/99 Visiting Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 1/92 – 1/09 Professor of Anthropology, University of Tulsa 6/91 - 6/95 Chair, Department of Anthropology 6/91 - 10/92 Acting Chair, Department of Sociology 8/88 - 1/92 Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Tulsa 8/82 - 7/88 Asst. Professor of Anthropology, University of Tulsa 9/81 - 6/82 Visiting Asst. Professor, Southwestern at Memphis 7/77 - 8/79 Visiting Research Scholar, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University FIELD RESEARCH: 7/16 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) 7/15 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) 7/14 Port Vila (Vanuatu) 7/13 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) 7/12 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) 7/11 - 8/11 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) 7/10 - 10/10 Port Vila; Tanna (Vanuatu) -

'John Frum Files' (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980)

Archiving a Prophecy. An ethnographic history of the ‘John Frum files’ (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980) Marc Tabani To cite this version: Marc Tabani. Archiving a Prophecy. An ethnographic history of the ‘John Frum files’ (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980). PAIDEUMA. Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, Frobenius Institute, 2018, 64. hal-01962249 HAL Id: hal-01962249 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01962249 Submitted on 9 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Paideuma 64:99-124 (2018) ARCHIVING A PROPHECY An ethnographie history of the 'John Frum files' (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941-1980) MarcTabani ABSTRACT. Repeated signs of a large-scale rebellion on the South Pacifie island of Tanna (Va nuatu) appeared in 1941. Civil disobedience was expressed through reference to a prophetic fig ure namedJohn Frum. In order to repress this politico-religious movement, categorized later as a cargo cult in the anthropological literature, the British administration accumulated thousands of pages of surveillance notes, reports and commentaries. This article proposes an introduction to the existence of these documents known as the 'John Frum files', which were classified as confidential until the last few years. -

Revitalization Movements in Melanesia: a Descriptive Analysis

Revitalization movements in Melanesia: a descriptive analysis Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Everett, Michael W. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 15:47:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318038 REVITALIZATION MOVEMENTS IN MELANESIA; A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS by Michael Wayne Everett A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 8 ISTATEMMT BI AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the library* Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission^ provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made0 Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Bean of . the Graduate College when in his judgment.the proposed use of the material is In the interests of scholarshipa In all other instances, however, permission -

Tanna Island - Wikipedia

Tanna Island - Wikipedia Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Tanna Island From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 19°30′S 169°20′E Tanna (also spelled Tana) is an island in Tafea Main page Tanna Contents Province of Vanuatu. Current events Random article Contents [hide] About Wikipedia 1 Geography Contact us 2 History Donate 3 Culture and economy 3.1 Population Contribute 3.2 John Frum movement Help 3.3 Language Learn to edit 3.4 Economy Community portal 4 Cultural references Recent changes Upload file 5 Transportation 6 References Tools 7 Filmography Tanna and the nearby island of Aniwa What links here 8 External links Related changes Special pages Permanent link Geography [ edit ] Page information It is 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 19 Cite this page Wikidata item kilometres (12 miles) wide, with a total area of 550 square kilometres (212 square miles). Its Print/export highest point is the 1,084-metre (3,556-foot) Download as PDF summit of Mount Tukosmera in the south of the Geography Printable version island. Location South Pacific Ocean Coordinates 19°30′S 169°20′E In other projects Siwi Lake was located in the east, northeast of Archipelago Vanuatu Wikimedia Commons the peak, close to the coast until mid-April 2000 2 Wikivoyage when following unusually heavy rain, the lake Area 550 km (210 sq mi) burst down the valley into Sulphur Bay, Length 40 km (25 mi) Languages destroying the village with no loss of life. Mount Width 19 km (11.8 mi) Bislama Yasur is an accessible active volcano which is Highest elevation 1,084 m (3,556 ft) Български located on the southeast coast. -

Pacific Island Cultures ANTH 350 ______Guido Carlo Pigliasco TR 7:30-8:45 Moore Hall 468 Classroom: Crawford 115 [email protected] Office Hrs: WF 11:30-12:30

Pacific Island Cultures ANTH 350 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Guido Carlo Pigliasco TR 7:30-8:45 Moore Hall 468 Classroom: Crawford 115 [email protected] Office Hrs: WF 11:30-12:30 Description Considered the largest geographical feature on earth, the Pacific Ocean displays an extraordinary human and cultural diversity. The Pacific has represented an object of European interest and fantasies since the European first age of discovery of the Oceanic region. In the popular imagination, the islands of the South Pacific conjure exotic images both serene and savage. ‘Islands of love’. Mysterious rituals. Cannibals stories. ‘Disappearing’ cultures. Threatened or ‘collapsed’ ecologies. These fantasies continue to reflect Western desires and discourses but have very little to do with how most Pacific Islanders live their lives today. Our focus is to analyze and discuss the contemporary reality, the entanglement of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ in the Pacific. As residents of a Pacific Island, students at the University of Hawai‘i will have an extraordinary opportunity to weave together western and Pacific ways of conveying and conceiving knowledge. The islands of Hawai‘i represent a critical intersection in cross-boundary Pacific identity formation. Using Hawai‘i as a point of departure—or arrival—the students will embark in an extraordinary journey through the social, cultural, ethnic, religious and politico-economic experiences of this complex and changing region and of the Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian communities represented. This body of knowledge, conveyed in reading assignments, lectures and occasional guest speakers’ testimonies, shall be approached in class from three different perspectives: contemporary realities, visual representations and panel discussions. -

Downloaded From: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and Many Other Open Repositories

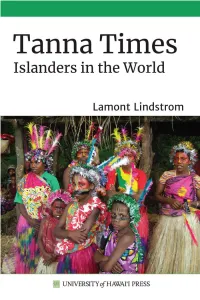

Tanna Times Islanders in the World • Lamont Lindstrom ‘ © University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Cover photo: Women and girls at a boy’s circumcision exchange, Ikurup village, . Photo by the author. is book is published as part of the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. With the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Pilot uses cutting-edge publishing technology to produce open access digital editions of high-quality, peer-reviewed monographs from leading university presses. Free digital editions can be downloaded from: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and many other open repositories. While the digital edition is free to download, read, and share, the book is under copyright and covered by the following Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND. Please consult www.creativecommons.org if you have questions about your rights to reuse the material in this book. When you cite the book, please include the following URL for its Digital Object Identier (DOI): https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle// We are eager to learn more about how you discovered this title and how you are using it. We hope you will spend a few minutes answering a couple of questions at this url: https://www.longleafservices.org/shmp-survey/ More information about the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot can be found at https://www.longleafservices.org. for Katiri, Maui, and Nora Rika • Woe to those who are at ease in Zion and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria. -

Margaret Mead's Wind Nation

LIKE FIRE THE PALIAU MOVEMENT AND MILLENARIANISM IN MELANESIA LIKE FIRE THE PALIAU MOVEMENT AND MILLENARIANISM IN MELANESIA THEODORE SCHWARTZ AND MICHAEL FRENCH SMITH MONOGRAPHS IN ANTHROPOLOGY SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464240 ISBN (online): 9781760464257 WorldCat (print): 1247150926 WorldCat (online): 1247151119 DOI: 10.22459/LF.2021 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: A Paliau Movement Supporter, Manus Province, Papua New Guinea, 2000, taken by Matt Tomlinson. This edition © 2021 ANU Press Contents List of illustrations . vii Acknowledgements . ix Preface: Why, how, and for whom . xi Spelling and pronunciation of Tok Pisin words and Manus proper names . xvii 1 . ‘The last few weeks have been strange and exciting’ . .1 2 . Taking exception . .27 3 . Indigenous life in the Admiralty Islands . .59 4 . World wars and village revolutions . .87 5 . The Paliau Movement begins . .121 6 . Big Noise from Rambutjo . .175 7 . After the Noise . .221 8 . The Cemetery Cult hides in plain sight . .247 9 . The Cemetery Cult revealed . .267 10 . Comparing the cults . 317 11 . Paliau ends the Cemetery Cult . .327 12 . Rise and fall . .361 13 . The road to Wind Nation . .383 14 . Wind Nation in 2015 . 427 15 . Probably not the last prophet .