Queercore: Queer Punk Media Subculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.9 - nº2 (2015), 207-223 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 207 Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer*** * PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) ** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) *** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) Abstract The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

D'eurockéennes

25 ans d’EUROCKÉENNES LE CRÉDIT AGRICOLE FRANCHE-COMTÉ NE VOUS LE DIT PAS SOUVENT : IL EST LE PARTENAIRE INCONTOURNABLE DES ÉVÉNEMENTS FRANCs-COMTOIS. IL SOUTIENT Retrouvez le Crédit Agricole Franche-Comté, une banque différente, sur : www.ca-franchecomte.fr Caisse Régionale de Crédit Agricole Mutuel de Franche-Comté - Siège social : 11, avenue Elisée Cusenier 25084 Besançon Cedex 9 -Tél. 03 81 84 81 84 - Fax 03 81 84 82 82 - www.ca-franchecomte.fr - Société coopérative à capital et personnel variables agréée en tant qu’établissement de crédit - 384 899 399 RCS Besançon - Société de courtage d’assurance immatriculée au Registre des Intermédiaires en Assurances sous le n° ORIAS 07 024 000. ÉDITO SOMMAIRE La fête • 1989 – 1992 > Naissance d’un festival > L’excellence et la tolérance, François Zimmer .......................................................p.4 > Une grosse aventure, Laurent Arnold ...................................................................p.5 continue > « Caomme un pèlerinage », Laurent Arnold ........................................................p.6 Les Eurockéennes ont 25 ans. Qui l’eut > Un air de Woodstock au pied du Ballon d’Alsace, Thierry Boillot .......................p.7 cru ? Et si aujourd’hui en 2013, un doux • 1993 – 1997 > Les Eurocks, place incontournable rêveur déposait sur la table le dossier d’un grand et beau festival de musiques > Les Eurocks, précurseurs du partenariat, Lisa Lagrange ..................................... p.8 actuelles (selon la formule consacrée), > Internet : le partenariat de -

Claiming Queer Territory in the Study of Subcultures and Popular Music

Claiming Queer Territory in the Study of Subcultures and Popular Music Author Taylor, J Published 2013 Journal Title Sociology Compass DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12021 Copyright Statement © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: Claiming Queer Territory in the Study of Subcultures and Popular Music, Sociology Compass, Vol. 7(3), 2013, pp. 194-207, which has been published in final form at dx.doi.org/10.1111/ soc4.12021. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/55644 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Sociology Compass 7/3 (2013): 194–207, 10.1111/soc4.12021 Claiming Queer Territory in the Study of Subcultures and PopularClaiming Music Queer Territory in the Study of Subcultures and ByPopular Jodie Taylor, Music Griffith University PublishedJodie Taylor* in Sociology Compass 7(3) 2013. Queensland Conservatorium Research Centre, Griffith University Abstract For both the heterosexual and queer subject, subcultural participation and stylistic modes of cul- tural production and consumption, including popular music, are critical mechanisms aiding in the construction and expression of identity. Yet, in spite of abundant empirical examples of queer music cultures, subcultural studies scholars have paid minimal attention to queer sexualities and their concomitant stylistic modalities. In this article, I claim the importance of queer subterranean music cultures by synthesising significant literatures from various fields of inquiry including cul- tural sociology, popular musicology and queer studies. To begin, I will briefly clarify to whom and about what queer (theory) speaks. I then go on to offer an overview of subcultural and popu- lar music research paying particular attention to the subaltern queer subject and surveying queer criticism within each field. -

The Queer History of Camp Aesthetics & Ethical

Seattle Pacific University Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring 6-7-2021 FROM MARGINAL TO MAINSTREAM: THE QUEER HISTORY OF CAMP AESTHETICS & ETHICAL ANALYSIS OF CAMP IN HIGH FASHION Emily Barker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Fashion Design Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Barker, Emily, "FROM MARGINAL TO MAINSTREAM: THE QUEER HISTORY OF CAMP AESTHETICS & ETHICAL ANALYSIS OF CAMP IN HIGH FASHION" (2021). Honors Projects. 118. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/118 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. FROM MARGINAL TO MAINSTREAM: THE QUEER HISTORY OF CAMP AESTHETICS & ETHICAL ANALYSIS OF CAMP IN HIGH FASHION by EMILY BARKER FACULTY MENTORS: ERICA MANZANO & SARAH MOSHER HONORS PROGRAM DIRECTOR: DR. CHRISTINE CHANEY A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree in Honors Liberal Arts Seattle Pacific University Presented at the SPU Honors Research Symposium June 7, 2021 1 Abstract: ‘Camp’ has become a buzzword in fashion over the last few years, due to a rise in popularity following the 2019 MET Gala theme, “Camp: Notes on Fashion.” Based on Susan Sontag’s 1964 book “Notes on Camp,” the event highlighted many aesthetic elements of Camp sensibilities, but largely ignores the importance of the LGBTQ+ community in Camp’s development. In this piece, I highlight various intersections of Camp and queerness over the last century and attempt to understand Camp’s place in High Fashion today. -

The History of Rock Music - the Eighties

The History of Rock Music - The Eighties The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Singer-songwriters of the 1980s (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Female folksingers 1985-88 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Once the effects of the new wave were fully absorbed, it became apparent that the world of singer-songwriters would never be the same again. A conceptual mood had taken over the scene, and that mood's predecessors were precisely the Bob Dylans, the Neil Youngs, the Leonard Cohens, the Tim Buckleys, the Joni Mitchells, who had not been the most popular stars of the 1970s. Instead, they became the reference point for a new generation of "auteurs". Women, in particular, regained the status of philosophical beings (and not only disco-divas or cute front singers) that they had enjoyed with the works of Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Suzy Gottlieb, better known as Phranc (1), was the (Los Angeles-based) songwriter who started the whole acoustic folk revival with her aptly-titled Folksinger (? 1984/? 1985 - nov 1985), whose protest themes and openly homosexual confessions earned her the nickname of "all-american jewish-lesbian folksinger". She embodied the historic meaning of that movement because she was a punkette (notably in Nervous Gender) before she became a folksinger, and because she continued to identify, more than anyone else, with her post- feminist and AIDS-stricken generation in elegies such as Take Off Your Swastika (1989) and Outta Here (1991). -

The South Wedge Quarterly

equal=grounds The South We dge Quarterly summer 2017 - volume v issue iv FREE hello The South Wedge Quarterly A PUBLICATION OF THE BUSINESS ASSOCIATION OF THE SOUTH WEDGE AREA | BASWA Editorial Board Chris Jones Karrie Laughton Katie Libby pride Rose O’Keefe Paula Frumusa Bridgette Pendleton-Snyder Lori Bryce I was not alone in wishing for a perfectly lovely transition from winter and spring into summer. Nor was Toni Beth Weasner I the only one wearing a hat, scarf and gloves while walking to admire flowering pear, plum and cherry Deb Zakrzewski trees. My rhododendron stayed at peak for three weeks thanks to those cold rains and freezing winds. [email protected] Art Production If you were to take some giant steps back through the centuries, I have no doubt that wishful think- ing about the weather and real hope for the future were part of the mix that tamed the forests in the Chris Jones Genesee Valley, led to the building of the Erie Canal and brought all the goods and ills of industrializa- John Magnus Champlin tion. In the South Wedge, I’ve had good company while celebrating recent changes. Jackie Evangelisti Advertising Sales Manager On the happy side, we’ve had the openings of one new venture after the next from Fountain of Youth Nancy Daley | [email protected] Fitness at the tip of South Avenue; to Abundance; to Relish fitting in so smoothly in Open Face’s spot; Time for Wine finally ready;Sujana Beauty and Brows, Just Browsing, and Highland Market Bakery Printed By & Deli, all within blocks of each other. -

Issue 171.Pmd

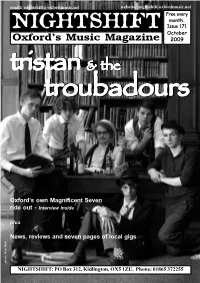

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Punk · Film RARE PERIODICALS RARE

We specialize in RARE JOURNALS, PERIODICALS and MAGAZINES Please ask for our Catalogues and come to visit us at: rare PERIODIcAlS http://antiq.benjamins.com music · pop · beat · PUNk · fIlM RARE PERIODICALS Search from our Website for Unusual, Rare, Obscure - complete sets and special issues of journals, in the best possible condition. Avant Garde Art Documentation Concrete Art Fluxus Visual Poetry Small Press Publications Little Magazines Artist Periodicals De-Luxe editions CAT. Beat Periodicals 296 Underground and Counterculture and much more Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT Visiting address: Klaprozenweg 75G · 1033 NN Amsterdam · The Netherlands Postal address: P.O. BOX 36224 · 1020 ME Amsterdam · The Netherlands tel +31 20 630 4747 · fax +31 20 673 9773 · [email protected] JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM cat.296.cover.indd 1 05/10/2016 12:39:06 antiquarian PERIODIcAlS MUSIC · POP · BEAT · PUNK · FILM Cover illustrations: DOWN BEAT ROLLING STONE [#19111] page 13 [#18885] page 62 BOSTON ROCK FLIPSIDE [#18939] page 7 [#18941] page 18 MAXIMUM ROCKNROLL HEAVEN [#16254] page 36 [#18606] page 24 Conditions of sale see inside back-cover Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM 111111111111111 [#18466] DE L’AME POUR L’AME. The Patti Smith Fan Club Journal Numbers 5 and 6 (out of 8 published). October 1977 [With Related Ephemera]. - July 1978. [Richmond Center, WI]: (The Patti Smith Fan Club), (1978). Both first editions. 4to., 28x21,5 cm. side-stapled wraps. Photo-offset duplicated. Both fine, in original mailing envelopes (both opened a bit rough but otherwise good condition). EUR 1,200.00 Fanzine published in Wisconsin by Nanalee Berry with help from Patti’s mom Beverly.