Architectural Encounters at Makli Necropolis (14Th – 18Th Centuries)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tentative Lists Submitted by States Parties As of 15 April 2021, in Conformity with the Operational Guidelines

World Heritage 44 COM WHC/21/44.COM/8A Paris, 4 June 2021 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Extended forty-fourth session Fuzhou (China) / Online meeting 16 – 31 July 2021 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8A. Tentative Lists submitted by States Parties as of 15 April 2021, in conformity with the Operational Guidelines SUMMARY This document presents the Tentative Lists of all States Parties submitted in conformity with the Operational Guidelines as of 15 April 2021. • Annex 1 presents a full list of States Parties indicating the date of the most recent Tentative List submission. • Annex 2 presents new Tentative Lists (or additions to Tentative Lists) submitted by States Parties since 16 April 2019. • Annex 3 presents a list of all sites included in the Tentative Lists of the States Parties to the Convention, in alphabetical order. Draft Decision: 44 COM 8A, see point II I. EXAMINATION OF TENTATIVE LISTS 1. The World Heritage Convention provides that each State Party to the Convention shall submit to the World Heritage Committee an inventory of the cultural and natural sites situated within its territory, which it considers suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, and which it intends to nominate during the following five to ten years. Over the years, the Committee has repeatedly confirmed the importance of these Lists, also known as Tentative Lists, for planning purposes, comparative analyses of nominations and for facilitating the undertaking of global and thematic studies. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Finding the Way (WILL)

A handbook for Pakistan's Women Parliamentarians and Political Leaders LEADING THE WAY By Syed Shamoon Hashmi Women's Initiative for Learning & Wi Leadership She has and shel willl ©Search For Common Ground 2014 DEDICATED TO Women parliamentarians of Pakistan — past, present and aspiring - who remain committed in their political struggle and are an inspiration for the whole nation. And to those who support their cause and wish to see Pakistan stand strong as a This guidebook has been produced by Search For Common Ground Pakistan (www.sfcg.org/pakistan), an democratic and prosperous nation. international non-profit organization working to transform the way the world deals with conflict away from adversarial approaches and towards collaborative problem solving. The publication has been made possible through generous support provided by the U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL), under the project titled “Strengthening Women’s Political Participation and Leadership for Effective Democratic Governance in Pakistan.” The content of this publication is sole responsibility of SFCG Pakistan. All content, including text, illustrations and designs are the copyrighted property of SFCG Pakistan, and may not be copied, transmitted or reproduced, in part or whole, without the prior consent of Search For Common Ground Pakistan. Women's Initiative for Learning & Wi Leadership She has and shel willl ©Search For Common Ground 2014 DEDICATED TO Women parliamentarians of Pakistan — past, present and aspiring - who remain committed in their political struggle and are an inspiration for the whole nation. And to those who support their cause and wish to see Pakistan stand strong as a This guidebook has been produced by Search For Common Ground Pakistan (www.sfcg.org/pakistan), an democratic and prosperous nation. -

Dr. Muhammad Hameed

Dr. Muhammad Hameed Chairman Associate Professor Department of Archaeology University of the Punjab (Archaeologist, Historian, Museologist, Field Expert, Heritage Expert) Profile Completed MA in Archaeology from University of the Punjab in 2004. Dr. Hameed joined Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab as Lecturer in 2006. After serving the university for five years and getting overseas scholarship, he went to Berlin, Germany and completed his PHD in Gandhara Art, in 2015 from Free University Berlin. During his stay in Berlin, got several opportunity to become a part of the international research circle and attended international conferences, symposiums and workshops, about different aspects of South Asian Archaeology, held in Paris, Stockholm, Berlin, and Torun. The main research focuses on Buddhist Art with special interest in the Miniature Portable Shrines from Gandhara and Kashmir. The PHD dissertation provides the first catalogue of these objects. Study of origin of miniature portable shrines, their, types, iconography and religious significance are the main features of my research. Articles related to research areas have been published in HEC recognized journals as well as in international journals. Personal Info S/O: Muhammad Rafique DOB: 16-09-1981 NIC: 35401-9809372-3 Domicile: Sheikhupura (Punjab) Nationality: Pakistani Contact Info Off.: 042-99230322 Mobile: 03344063481 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Address: Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan Experience February -

Bird Conservation International Population and Spatial Breeding

Bird Conservation International http://journals.cambridge.org/BCI Additional services for Bird Conservation International: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan CAMPBELL MURN, UZMA SAEED, UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Bird Conservation International / FirstView Article / December 2014, pp 1 - 11 DOI: 10.1017/S0959270914000483, Published online: 16 December 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0959270914000483 How to cite this article: CAMPBELL MURN, UZMA SAEED, UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan. Bird Conservation International, Available on CJO 2014 doi:10.1017/S0959270914000483 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BCI, IP address: 82.152.44.144 on 17 Dec 2014 Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 11 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S0959270914000483 Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan CAMPBELL MURN , UZMA SAEED , UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Summary The Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis has declined across most of its range by over 95% since the mid-1990s. The primary cause of the decline and an ongoing threat is the ingestion by vultures of livestock carcasses containing residues of non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, principally diclofenac. Recent surveys in Pakistan during 2010 and 2011 revealed very few vultures or nests, particularly of White-backed Vultures. -

Conservation 2006 DAP-NEDUET

ARCHIVES Conservation 2006 DAP-NEDUET NEWSPAPER CLIPPING AuthorAgency Title Page News Paper Type New Paper Name Date Last First Page No. No. Kalhoro Zulfiqar Ali A glorious past Article Daily Dawn M 3 8-Jan-06 1 Anwar Mushir Shigar Fort-fabulous inn on road to K-2 Article Daily Dawn M 2 8-Jan-06 2 Haider Eeftikhar Shiva's valley Article The News 31 15-Jan-06 3 Bhagwandas Illegal contruction at protected site Article Daily Dawn 13,14 13-Feb-06 4 Bhagwandas Building faces demolition threat KBCA directed to Shafquat House protection Article Daily Dawn 14 6-Mar-06 6 Ezdi Rabia In defence of the fort Article The News 31 12-Mar-06 7 Ghori Habib Khan Experts want historical sites under Sindh govt Article Daily Dawn 18 6-May-06 8 Kalhoro M. R Rs35m approved for Moenjodaro rehabilitation Article Daily Dawn 5 11-May-06 9 Tahir Zulqernain British-era clock tower demolished Article Daily Dawn 12 9-Jun-06 10 Bhagwandas Original stone walls uncovered at Wazir Mansion Article Daily Dawn 18 22-Jun-06 11 Bhagwandas Rs 35m project approved for Moenjodaro Rehabilitation Article Daily Dawn 15 24-Jul-06 12 Paracha Abdul Sami Historcial sites lose original look Article Daily Dawn 22 25-Jul-06 13 Bhagwandas Napa ordered to stop work at Hindu Gymkhana Article Daily Dawn 18 17-Aug-06 14 Ansari Afzal Mega Bulleh Shah project in ruins Article Daily Dawn 4 26-Aug-06 15 Zaman Mahmood Resting with Anarkali Article Daily Dawn M 2 26-Aug-06 16 Ali Sarwat No love among the ruins Article The News 32 24-Sep-06 17 Baig Gulzar Gurdwara falls into disrepair Article Daily -

Judicial System in India During Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources

Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources (Nezam-e-dadgahi-e-Hend der ahd-e-Gorkanian bewizha-e manabe-e farsi) For the Award ofthe Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted by Md. Sadique Hussain Under the Supervision of Dr. Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari Center Qf Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. 2009 Center of Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. Declaration Dated: 24th August, 2009 I declare that the work done in this thesis entitled "Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with special reference to Persian sources", for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy, submitted by me is an original research work and has not been previously submitted for any other university\Institution. Md.Sadique Hussain (Name of the Scholar) Dr.Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari (Supervisor) ~1 C"" ~... ". ~- : u- ...... ~· c "" ~·~·.:. Profess/~ar Mahdi 4 r:< ... ~::.. •• ~ ~ ~ :·f3{"~ (Chairperson) L~.·.~ . '" · \..:'lL•::;r,;:l'/ [' ft. ~ :;r ':1 ' . ; • " - .-.J / ~ ·. ; • : f • • ~-: I .:~ • ,. '· Attributed To My Parents INDEX Acknowledgment Introduction 1-7 Chapter-I 8-60 Chapter-2 61-88 Chapter-3 89-131 Chapter-4 132-157 Chapter-S 158-167 Chapter-6 168-267 Chapter-? 268-284 Chapter-& 285-287 Chapter-9 288-304 Chapter-10 305-308 Conclusion 309-314 Bibliography 315-320 Appendix 321-332 Acknowledgement At first I would like to praise God Almighty for making the tough situations and conditions easy and favorable to me and thus enabling me to write and complete my Ph.D Thesis work. -

East Bengal Tables , Vol-8, Pakistan

M-Int 17 5r CENSlUJS Of PAIK~STAN, ~95~ VOLUME 6 REPORT & TABLES BY GUl HASSAN, M. I. ABBASI Provincial Superintendent of Census, SIND Published by the Man.ager of Publication. Price Rs. J 01-1- FIRST CENSUS OF PAKISTAN. 1951 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS Bulletins No. I--Provisional Tables of Population. No. 2--Population according to Religion. No.3-Urban and Rural Population and Area. No.4-Population according to Economic Categories. Village Lists The Village list shows the name of every Village in Pakistan in its place in the ltthniftistra tives organisation of Tehsils, Halquas, Talukas, Tapas, SUb-division's Thanas etc. The names are given in English and in the appropriate vernacular script, and against _each is shown the area, population as enumerated in the Census, tbe number of houses, and local details such as the existence of Railway Stations, Post Offices, Schools, Hospitals etc. The Village -list. is issued in separate booklets for each District or group of Districts. Census Reports Printed Vol. 2-Baluchistan and States Union Report and Tables. Vol. 3.-East Bengal Report and Tables. Vol. 4-N.-W. F. P. and Frontier Regions Report :md Tables. Vol. 6-Sind and Khairpur State Report and Tabla Vol 8-East Pakistan Tables of Economic CharacUi Census Reports (in course of preparation.) Vol. I-General Report and Tables for Pakistan, shcW)J:}g Provincial Totals. Vol. 5-Punjab and Bahawalpur State Report and Tables. Vol. 7-West Pakistan Tables ot Economic Characteristics.- PREF ACE, This Census Report for the province of Sind and Khairpur State is one of the series 'of volumes in which the results ofothe 1951 €ensus of Pakistan are recorded. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

WHW Report 2018

W H W World Heritage Watch Report 2018 World Heritage Watch Report 2018 Report Watch Heritage World World Heritage Watch Heritage World World Heritage Watch World Heritage Watch Report 2018 Berlin 2018 2 Bibliographical Information World Heritage Watch: World Heritage Watch Report 2018. Berlin 2018 184 pages, with 217 photos and 53 graphics and maps Published by World Heritage Watch e.V. Berlin 2018 ISBN 978-3-00-059753-4 NE: World Heritage Watch 1. World Heritage 2. Civil Society 3. UNESCO 4. Participation 5. Natural Heritage 6. Cultural Heritage 7. Historic Cities 8. Sites 9. Monuments 10. Cultural Landscapes 11. Indigenous Peoples 12. Participation W H W © World Heritage Watch e.V. 2018 This work with all its parts is protected by copyright. Any use beyond the strict limits of the applicable copyright law without the consent of the publisher is inadmissable and punishable. This refers especially to reproduction of figures and/or text in print or xerography, translations, microforms and the data storage and processing in electronical systems. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the publishers concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the frontiers of any country or territory. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of the editors, and do not commit them. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publishers except for the quotation of brief passages for the purposes of review. -

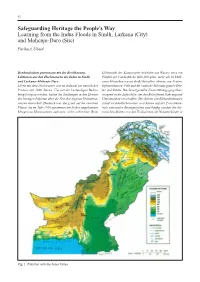

And Mohenjo-Daro (Site) Fariha A

62 Safeguarding Heritage the People’s Way Learning from the Indus Floods in Sindh, Larkana (City) and Mohenjo-Daro (Site) Fariha A. Ubaid Denkmalschutz gemeinsam mit der Bevölkerung. Höhepunkt der Katastrophe bedeckte das Wasser etwa ein Lektionen aus den Hochwassern des Indus in Sindh Fünftel der Landesfläche (800,000 qkm), mehr als 20 Milli- und Larkana–Mohenjo-Daro onen Menschen waren direkt betroffen, ebenso wie Ernten, Leben mit dem Hochwasser war im Industal ein natürlicher Infrastrukturen, Vieh und die bauliche Substanz ganzer Dör- Prozess seit 5000 Jahren. Um mit der beständigen Bedro- fer und Städte. Die bereitgestellte Unterstützung ging über- hung fertig zu werden, hatten die Siedlungen in den Ebenen wiegend in die Soforthilfe, um den Betroffenen Nahrung und des heutigen Pakistan über die Zeit ihre eigenen Verhaltens- Unterkunft zu verschaffen. Der Schutz von Kulturdenkmalen weisen entwickelt. Dennoch war das Land auf die enormen stand verständlicherweise weit hinten auf der Prioritäten- Fluten, die im Jahr 2010 zusammen mit bisher ungekannten liste nationaler Strategiepläne und häufig wurden die his- Mengen an Monsunregen auftraten, nicht vorbereitet. Beim torischen Stätten von den Evakuierten als Notunterkünfte in Fig. 1: Pakistan with the Indus Valley Safeguarding Heritage the People’s Way ... 63 Beschlag genommen. Der Wiederaufbau bedeutete vor allem die Errichtung neuer Häuser und Infrastruktur. Der Beitrag gibt einen Überblick über die Hochwasser- probleme und Vorsorgemaßnahmen bei den wichtigsten Denkmalstätten im Industal. Technisch-zivilisatorische Interventionen in die Landschaft, wie Dämme, Wehre, Ka- näle, Bewässerungssysteme und Hochwasserschutz-Vor- kehrungen, werden vor dem Hintergrund der historischen Bedeutung der Indus-Kulturen betrachtet. Mit einem der- art übergreifenden Blick wird für das Gebiet der heutigen Stadt Larkana und der benachbarten archäologischen Welterbestätte Mohenjo-Daro eine Analyse der Flutereig- nisse durchgeführt. -

Innovative Educator Experts

Innovative Educator Experts 2019-2020 The Microsoft Innovative Educator (MIE) Expert program is an exclusive program created to recognize global educator visionaries who are using technology to pave the way for their peers for better learning and student outcomes. Microsoft Innovative Educator Experts Names are sorted by region, then country, then last name. Table of Contents Contents Asia Pacific Region ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Bangladesh ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Brunei .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Cambodia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Indonesia .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Korea ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................