Senate Select Committee on Regional and Remote Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palaeoworks Technical Papers 9

Palaeoworks Technical Papers 9 Geochemistry and identification of Australian red ochre deposits Mike Smith & Barry Fankhauser National Museum of Australia, Canberra, ACT 2601 and Centre for Archaeological Research, Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected] September 2009 Note This information has been prepared for students and researchers interested in identifying ochre in archaeological contexts. It is open to use by everyone with the proviso that its use is cited in any publications, using the URL as the place of publication. Any comments regarding the information found here should be directed to the authors at the above address. © Mike Smith & Barry Fankhauser 2009 Preface Between 1994 and 1998 the authors undertook a project to look at the feasibility of using geochemical signatures to identify the sources of ochres recovered in archaeological excavations. This research was supported by AIATSIS research grants G94/4879, G96/5222 and G98/6143.The two substantive reports on this research (listed below) have remained unpublished until now and are brought together in this Palaeoworks Technical Paper to make them more generally accessible to students and other researchers. Smith, M. A. and B. Fankhauser (1996) An archaeological perspective on the geochemistry of Australian red ochre deposits: Prospects for fingerprinting major sources. A report to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra. Smith, M. A. and B. Fankhauser (2003) G96/5222 - Further characterisation and sourcing of archaeological ochres. A report to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra. The original reports are reproduced substantially as written, with the exception that the tables listing samples from ochre quarries (1996: Tables II/ 1-11) have been revised to include additional samples. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

Ali Curung CDEP

The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities: Support document JOSIE MISKO This document was produced by the author(s) based on their research for the report, The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities, and is an added resource for further information. The report is available on NCVER’s website: <http://www.ncver.edu.au> The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author(s). SUPPORT DOCUMENT e Need more information on vocational education and training? Visit NCVER’s website <http://www.ncver.edu.au> 4 Access the latest research and statistics 4 Download reports in full or in summary 4 Purchase hard copy reports 4 Search VOCED—a free international VET research database 4 Catch the latest news on releases and events 4 Access links to related sites Contents Contents 3 Regional Council – Roma 4 Regional Council – Tennant Creek 7 Ali Curung CDEP 9 Bidjara-Charleville CDEP 16 Cherbourg CDEP 21 Elliot CDEP 25 Julalikari CDEP 30 Julalikari-Buramana CDEP 33 Kamilaroi – St George CDEP 38 Papulu Apparr-Kari CDEP 42 Toowoomba CDEP 47 Thangkenharenge – Barrow Creek CDEP 51 Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (2002) 53 Institute of Aboriginal Development 57 Julalikari RTO 59 NCVER 3 Regional Council – Roma Regional needs Members of the regional council agreed that the Indigenous communities in the region required people to acquire all the skills and knowledge that people in mainstream communities required. -

Central Land Council and Northern Land Council

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL and NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Productivity Commission Draft Report into Resources Sector Regulation 21 August 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. KEY TERMS ____________________________________________________________ 4 2. INTRODUCTION ________________________________________________________ 5 PART 1 – DETAILED RESPONSE AND COMMENTARY_________________________ 5 3. LEGAL CONTEXT _______________________________________________________ 5 3.1. ALRA NT ______________________________________________________________ 5 3.2. Native Title Act _________________________________________________________ 6 3.3. The ALRA NT is not alternate to the Native Title Act. __________________________ 6 4. POLICY CONTEXT ______________________________________________________ 6 4.1. Land Council Policy Context ______________________________________________ 6 4.2. Productivity Commission consultation context ________________________________ 8 5. RECOMMENDATIONS AND COMMENTS __________________________________ 9 5.1. The EPBC Act, and Northern Territory Environmental Law has recently been subject to specialised review _________________________________________________________ 9 5.2. Pt IV of the ALRA NT has recently been subject to specialised review _____________ 9 5.3. Traditional owners are discrete from the Aboriginal Community and have special rights ____________________________________________________________________ 10 5.4. Free Prior Informed Consent _____________________________________________ 11 5.5. Inaccuracies in the draft Report -

Central Land Council Confines It’S Submission to the Following Terms of Reference, As They Relate to the Protection of Sacred Sites in the Northern Territory

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia – Inquiry into the destruction of 46,000 year old caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara region of Western Australia August 2020 Contents Terms of Reference ................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations .................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 7 Guiding principles when reviewing Indigenous heritage legislation ...................................... 8 Term of reference (f): The interaction of state indigenous heritage regulations with Commonwealth laws................................................................................................................. 9 Interaction of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act (Cth) with the Northern Territory Sacred Sites Act ....................................................................................... 9 The ATSIHP Act .................................................................................................................... -

ISX – the First Five Years (2004-2009) and the Next Five

New Thinking from the ISX on Remote Area Transport, Plant for Indigenous Contractors, Office Space, Homelands Enterprises & Housing Infrastructure This paper is about how non-Indigenous and Indigenous owned mining companies can make a difference in remote and regional Indigenous communities by building the transport, business and housing infrastructure capacity of Indigenous communities through targeted 100 per cent tax deductible donations of cash, equipment and services. This strategy has many benefits. It can be a means of supporting Aboriginal contractors to build an independent business asset base and capacity, increasing the self sufficiency of Indigenous communities and reducing the high cost of living in mining regions. Kevin Fong, Chairman and Peter Botsman, Secretary, ISX Paper for the Aboriginal Enterprises in Mining, Energy and Exploration Conference and the Minerals Council of Australia Conference, Adelaide, October 2009 www.isx.org.au 1 Reducing the High Costs of Transport in Indigenous Communities In 2010 the ISX, in honour of its deep roots in Broome, agreed to think hard about the question of the high cost of transport and vehicles for remote and regional Aboriginal communities throughout Australia. Broome’s Aboriginal taxi drivers were legendary, pioneer business-people who directly benefited the community and led to lower costs of transport for Aboriginal people. They were also the heart and soul of the community and were problem solvers and unofficial community guardians. Today in many remote communities it can cost as much as $A450 for a single one-way trip to a supermarket to purchase food for a community. There are no buses and most communities have to add these costs on to the already very highly inflated prices of food and sustenance. -

Yukultji Napangati - Pintupi

YUKULTJI NAPANGATI - PINTUPI Represented by Utopia Art Sydney 983 Bourke St, Waterloo NSW 2017 Tel: 61 2 9319 6437 utopiaartsydney.com.au [email protected] Yukultji Napangati is a rising star of the Papunya Tula Artists. She first came to the notice of a wider audience through her inclusion in the 2005 Primavera exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia. She is renowned for her shimmering surfaces and subtle use of colour, however, as an artist, she continues to explore all possibilities. Born circa 1971 near Wilkinkarra (Lake Mackay), “Yukultji was still a young girl when her family group came out of the desert into Kiwirrkurra in 1984, making national headlines as the ‘last’ of the desert nomads to make ‘first contact’” (Vivien Johnson, 2008). Yukultji began painting for Papunya Tula Artists in 1996. Her work is included in significant public and private collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the Hood Museum of Art, USA. Yukultji won the Wynne Prize at the AGNSW in 2018. Awards 2018 Winner ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2013 Highly Commended ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2012 Winner, ‘The Alice Prize’ 2011 Highly Commended, ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales Solo Exhibitions 2020 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW 2019 Yukultji Napangati, Salon94, New York, USA 2014 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW Selected Group Exhibitions 2020 ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney -

Infrastructure Requirements to Develop Agricultural Industry in Central Australia

Submission Number: 213 Attachment C INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS TO DEVELOP AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN CENTRAL AUSTRALIA 132°0'0"E 133°0'0"E 134°0'0"E 135°0'0"E 136°0'0"E 137°0'0"E Aboriginal Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Allocation fully economic Requirements Area (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Karlantijpa 1000 20 Tennant ALT Creek + Warumungu $12m $3.94m Frewena ALT 2000 40 (Frewena) 19°0'0"S Frewena 19°0'0"S LIKKAPARTA Tennant Creek Karlantijpa ALT Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements 20°0'0"S (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) 20°0'0"S Illyarne ALT 1500 30 Warrabri ALT 4000 100 $2.9m Western MUNGKARTA Murray $26m (Already Davenport Downs & invested via 1000 ABA $3.5m) Singleton WUTUNUGURRA Station CANTEEN CREEK Illyarne ALT Murray Downs and Singleton Stations ALI CURUNG 21°0'0"S 21°0'0"S WILLOWRA TARA Warrabri ALT AMPILATWATJA WILORA Ahakeye ALT (Community farm) ARAWERR IRRULTJA 22°0'0"S NTURIYA 22°0'0"S PMARA JUTUNTA YUENDUMU YUELAMU Ahakeye ALT (Adelaide Bore) A Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & B Water LARAMBA Control Aboriginal Land Water jobs when direct Infrastructure C District Trust (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements Ahakeye ALT (6 Mile farm) (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Ahakeye ALT Pine Hill Block B ENGAWALA community farm 30 5 ORRTIPA-THURRA Adelaide bore 1000 20 Ti-Tree $14.4m $3.82m Ahakeye ALT (Bush foods precinct) Pine Hill ‘B’ 1800 20 BushfoodsATITJERE precinct 70 5 6 mile farm 400 10 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S PAPUNYA Potentia Potential Approximate Bore Field & HAASTS BLUFF Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust l Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocati fully economic Requirements on (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) A.S. -

Indigenous Archives

INDIGENOUS ARCHIVES 3108 Indigenous Archives.indd 1 14/10/2016 3:37 PM 15 ANACHRONIC ARCHIVE: TURNING THE TIME OF THE IMAGE IN THE ABORIGINAL AVANT-GARDE Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll Figure 15.1: Daniel Boyd, Untitled TI3, 2015, 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, All the World’s Futures. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: la Biennale di Venezia. Daniel Boyd’s Untitled T13 (2015) is not an Aboriginal acrylic dot painting but dots of archival glue placed to match the pixel-like 3108 Indigenous Archives.indd 342 14/10/2016 3:38 PM Anachronic Archive form of a reproduction from a colonial photographic archive. Archival glue is a hard, wax-like material that forms into lumps – the artist compares them to lenses – rather than the smooth two- dimensional dot of acrylic paint. As material evidence of racist photography, Boyd’s paintings in glue at the 2015 Venice Biennale exhibition physicalised the leitmotiv of archives. In Boyd’s Untitled T13 the representation of the Marshall Islands’ navigational charts is an analogy to the visual wayfinding of archival photographs. While not associated with a concrete institution, Boyd’s fake anachronic archive refers to institutional- ised racism – thus fitting the Biennale curator Okwui Enwezor’s curatorial interest in archival and documentary photography, which he argues was invented in apartheid South Africa.1 In the exhibition he curated in 2008, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, Enwezor diagnosed an ‘archival fever’ that had afflicted the art of modernity since the invention of photography. The invention, he believed, had precipitated a seismic shift in how art and temporality were conceived, and that we still live in its wake. -

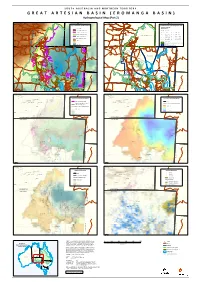

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

Family News 67

Family News Edition 67 Lexi Ward from Aputula and story on pg4 © Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation “ doing good work with families” Postal: PO Box 8274 Alice Springs NT 0871 Location: 3 Ghan Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Ph: (08) 8953 4488 Fax: (08) 89534577 Website: www.waltja.org.au Waltja Chairperson 2020ngka ngarangu watjil, watjilpa, tjilura, tjiluru nganampa Waltja tjutaku. Ngurra tjutanya patirringu marrkunutjananya ngurrangka nyinanytjaku wiya tawunukutu ngalya yankutjaku. Tjananya watjanu wiya, ngaanyakuntjaku Waltja kutjupa tjutangku tjana patikutu nyinangi Waltjangku, katjangku, yuntalpanku, tjamuku nyaakuntja wiya. Ngurra purtjingka nyinapaiyi tjutanya, Kapumantaku marrkunu tjananya nyinantjaku ngurrangka Tjanaya watjil watjilpa, nyinangi wiya nganana yuntjurringnyi tawunukatu yankutjaku mangarriku, yultja mantjintjaku Waltjalu? Tjanampa yiyanangi yultja tjuta ngurra winkikutu. Tjana yunparringu ngurra winkinya mangarriku Walytjalu yiyanutjangka. Walytjalu yilta tjananya puntura alpamilaningi. Panya Sharijnlu watjanutjangka. Yanangi warrkana tjutanya ngurra tjutakutu. Youth worker, NDIS, culture anta governance tjuta warrkanarripanya Walytjaku kimiti tjutanyalatju tjungurrikula miitingingka wankangi 12 times Member tjutangku miitingingka wangkangi AGM miitingi. Panya minta kuyangkulampa yangatjunu. AGM miitingi ngaraku March-tjingka (2021-ngngka) Nganana yuntjurrinyi minmya tjutaku ngurra tjutaku. Yukarraku, Ulkumanuku, nganana yuntjurringanyi. Palyaya nyinama ngurrangka Walytja tjuta kunpurringamaya. Palya Nangala. 2020 was a hard year, a sad year for people. The remote communities were locked down and no visiting each other. No shopping in Alice Springs. Everyone was crying for warm clothes and food. Oh we were too busy at Waltja clothes and food everywhere! Sending to every community. The rest of the year we were working with Sharijn to do all the programs, help the workers to go bush. Youth work, NDIS, culture and governance work.