What Works for Adolescents' Empowerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Good Luck!

INDIA YEAR BOOK - 2017 INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Dear Students, With the focus on the provision of best study material to our students, Rau’s IAS Study Circle is innovatively presenting the voluminous INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 in a very concise and lucid manner. Through this, efforts have been taken to circulate the best synopsis extracted from the Year Book-2017 for the benefit of the students. The abstract has been designed to present contents of the year book in most user-friendly manner. All the major and important points are given in bold and highlighted. The content is also supported by figures and pictures as per the requirement. The content has been chosen and compiled judiciously so that maximum coverage of all the relevant and significant material is presented within minimum readable pages. The issue titled ‘INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 will be covering the following topics: 1. Land and the People 16. Health and Family Welfare 2. National Symbols 17. Housing 3. The Polity 18. India and the World 4. Agriculture 19. Industry 5. Culture and Tourism 20. Law and Justice 6. Basic Economic Data 21. Labour, Skill Development and Employment 7. Commerce 22. Mass Communication 8. Communications and Information Technology 23. Planning 9. Defence 24. Rural and Urban Development 10. Education 25. Scietific and Technological Developments 11. Energy 26. Transport 12. Environment 27. Water Resources 13. Finance 28. Welfare 14. Corporate Affairs 29. Youth Affairs and Sports 15. Food and Civil Supplies By providing this, the Study Circle hopes that all the students will be able to make the best use of it as a ready reference material and allay their fears of perusing and cramming the entire year book. -

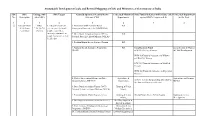

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of Csss and Ministries of Government of India

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. Description other SDGs Schemes (CSS) Departments against SDG's Targets (col. 4) in the State 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ① End poverty in SDGs 1.1 By 2030, eradicate 1. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural RD all its forms 2,3,4,5,6,7,8, extreme poverty for all Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) everywhere 10,11,13 people everywhere, currently measured as 2. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY) - RD people living on less than National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) $1.25 a day 3. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana - Gramin RD 4. National Social Assistance Programme RD Social Security Fund Social Secuity & Women (NSAP) SSW-03) Old Age Pension & Child Development. WCD-03)Financial Assistance to Widows and Destitute women SSW-04) Financial Assistance to Disabled Persons WCD-02) Financial Assistance to Dependent Children 5. Market Intervention Scheme and Price Agriculture & Agriculture and Farmers Support Scheme (MIS-PSS) Cooperation, AGR-31 Scheme for providing debt relief to Welfare the distressed farmers in the state 6. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY)- Housing & Urban National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM) Affairs, 7. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana -Urban Housing & Urban HG-04 Punjab Shehri Awaas Yojana Housing & Urban Affairs, Development 8. Development of Skills (Umbrella Scheme) Skill Development & Entrepreneurship, 9. Prime Minister Employment Generation Micro, Small and Programme (PMEGP) Medium Enterprises, 10. Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana Labour & Employment Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. -

Urban Development in India: a Special Focus Public Finance Newsletter

Urban development in India: A special focus Public Finance Newsletter Issue XI March 2016 In this issue 2 Feature article 10 Pick of the quarter 20 Round the corner 22 Potpourri 24 PwC updates Knowledge is the only instrument of production that is not subject to diminishing returns. J M Clark Dear readers, ‘Round the corner’ provides news updates in the area of government finances and policies across the The above quotation from the globe and key paper releases in the public finance American economist still domain during the recent months, along with holds true. Knowledge reference links. The ‘Our work’ section presents a increases by sharing and our mid-term review of the Support Program for Urban initiative to share knowledge, Reforms (SPUR), Bihar, which was conducted by views and experiences in the our team for the Department for International public finance domain Development (DFID). SPUR is a six-year through this newsletter has given us returns in the programme being implemented by the Government form of readers and contributors from across the of Bihar in partnership with DFID in 29 urban local globe. In continuation with our efforts in this bodies of Bihar. direction, I welcome you to the eleventh issue of the Public Finance Newsletter. I would like to thank you for your overwhelming support and response. Your suggestions urge us to The feature article in this issue aims to delve continuously improve this newsletter to ensure deeper into India’s urban development agenda. effective information sharing. Last year, we witnessed the launch of new missions such as Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban We would like to invite you to contribute and share Transformation (AMRUT), which replaced the your experiences in the public finance space with Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission us. -

Body of Knowledge Improving Sexual & Reproductive Health for India’S Adolescents 2 Body of Knowledge USAID

Body of Knowledge Improving Sexual & Reproductive Health for India’s Adolescents 2 Body of Knowledge USAID The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the United States federal government agency that provides economic development and humanitarian assistance around the world in support of the foreign policy goals of the United States. USAID works in over 100 countries around the world to promote broadly shared economic prosperity, strengthen democracy and good governance, protect human rights, improve global health, further education and provide humanitarian assistance.This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Dasra and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. KIAWAH TRUST The Kiawah Trust is a UK family foundation that is committed to improving the lives of vulnerable and disadvantaged adolescent girls in India. The Kiawah Trust believes that educating adolescent girls from poor communities allows them to thrive, to have greater choice in their life and a louder voice in their community. This leads to healthier, more prosperous and more stable families, communities and nations. PIRAMAL FOUNDATION Piramal Foundation strongly believes that there are untapped innovative solutions that can address India’s most pressing problems. Each social project that is chosen to be funded and nurtured by the Piramal Foundation lies within one of the four broad areas - healthcare, education, livelihood creation and youth empowerment. The Foundation believes in developing innovative solutions to issues that are critical roadblocks towards unlocking India’s economic potential. -

The Policy Environment for Food, Agriculture and Nutrition in India: Taking Stock and Looking Forward

LANSA WORKING PAPER SERIES Volume 2017 No 15 The Policy Environment for Food, Agriculture and Nutrition in India: Taking Stock and Looking Forward Lina Sonne July 2017 About this paper This paper is part of a project titled FAN Innovation Systems and Institutions: Enabling Alternative Policy Frameworks for Food, Agriculture and Nutrition funded by Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia (LANSA) Research Consortium Programe under the first Responsive Window grant funds. We thank Huma Tariq and Anjali Neelakantan for research assistance and Mona Dhamankar and Jessica Seddon for advice. About LANSA Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia (LANSA) is an international research partnership. LANSA is finding out how agriculture and agri-food systems can be better designed to advance nutrition. LANSA is focused on policies, interventions and strategies that can improve the nutritional status of women and children in South Asia. LANSA is funded by UK aid from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government's official policies. For more information see www.lansasouthasia.org 2 Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2016-17

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 MINISTRY OF WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT Government of India Annual Report 2016-17 i CONTENTS Page No. Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. Women Empowerment and Protection 5 Chapter 3. Child Development 25 Chapter 4. Child Protection and Welfare 53 Chapter 5. Gender Budgeting 79 Chapter 6 Plan, Statistics & Research 87 Chapter 7. Other Programmes & Activities 95 Chapter 8. Food and Nutrition Board 109 Chapter 9. National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 119 Chapter 10. Central Social Welfare Board 129 Chapter 11. National Commission for Women 141 Chapter 12. Rashtriya Mahila Kosh 157 Chapter 13. National Commission for Protection of Child Rights 165 Chapter 14. Central Adoption Resource Authority 183 Annexures 193 Annual Report 2016-17 iii 1 Introduction Annual Report 2016-17 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 The Ministry of Women and Child Mission - Children Development, Government of India, came into existence as a separate Ministry with effect 1.4 Ensuring development, care and protection from 30th January, 2006. In 2014, the Ministry of children through cross-cutting policies and was headed for the first time by a Cabinet rank programmes, spreading awareness about their Minister. It has the nodal responsibility to advance rights and facilitating access to learning, nutrition, the rights and concerns of women and children institutional and legislative support for enabling who together constitute 67.7% of the country’s them to grow and develop to their full potential. population, as per 2011 Census. The Ministry was Constitutional and Legal Provisions for constituted with the prime intention of addressing Women and Children gaps in State action for women and children and for promoting inter-ministerial and inter-sectoral 1.5 The makers of our Constitution were convergence to create gender equitable and child- concerned for the equality and rights of women centered legislation, policies and programmes. -

Infant, Toddler, Caregiver-Friendly Neighbourhood

INFANT, TODDLER, CAREGIVER-FRIENDLY NEIGHBOURHOOD POLICY WORKBOOK The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs is the apex authority of Government of India to formulate policies, coordinate the activities of various Central Ministries, State Governments and other nodal authorities and monitor programmes related to issues of housing and urban affairs in the country. The Smart Cities Mission was launched by the Ministry in 2015 to promote sustainable and inclusive cities that provide core infrastructure and give decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of ‘Smart’ Solutions. http://mohua.gov.in/ Founded in 1949, the Bernard van Leer Foundation (BvLF) is a private founda- tion focused on developing and sharing knowledge about what works in early childhood development. It provides financial support and expertise to partners in government, civil society and business to help test and scale effective services for young children and families. Urban95 is the Bernard van Leer Foundation’s 30 million euro initiative to make lasting change in the landscapes and opportuni- ties that shape the crucial first five years of children’s lives. BvLF has supported programs in India since 1992. https://bernardvanleer.org/ Founded in 1961, BDP is one of the largest interdisciplinary design led firm in Europe and has won over 750 awards for design quality from international and national bodies. BDP established a studio in India in 2010, and has worked on projects at every scale, from city masterplans to detailed public realm design; from concept through to delivery. BDP brings skills involved in the design of great spaces and environments into a single, managed service. -

ESI Question Paper – RBI GRADE B 2017 Phase 2 1

ESI question paper – RBI GRADE B 2017 phase 2 1. Brundtland commission is also known as? a. World commission on sustainable development b. World commission on environment and development c. World commission on global warming d. Commission on ozone layer depletion 2. ASEAN summit 2017 was held at a. Singapore b. Manila c. Beijing d. Tokyo 3. According to 2011 secc census, what is the percentage of rural households in India a. 67 b. 73 c. 80 d. 64 4. According to a global advocacy group on water and sanitation how many Indians in rural areas do not have access to clean drinking water? a. 33 million b. 53 million c. 63 million d. 43 million 5. Human development index is released by which global institution a. United nations development programme b. World bank group c. IMF d. ECOSOC 6. GDP-DEPRECIATION= a. NNP b. NDP c. GNP d. GNA 7. Market value of all the final goods and services produced in a country is known as a. GDP b. GNP c. National income d. GVA 8. What does D stand in the term FSDC a. Depreciation b. Domestic c. Drought d. Development 9. Which country has ratified automatic exchange of financial information with India and 40 other countries a. Cayman islands b. Panama c. Switzerland d. Panama 10. Which among the following countries or group has opt out of the paris climate agreement? a. European union b. USA c. UK d. China 11. FRBM review report was submitted by which committee a. Bibek debroy b. N K singh c. -

India Year Book January 2020

IAS JOIN THE DOTS India Year Book Series A Gist of India Year Book (2020 Issue) /CLIasofficial tiny.cc/o64v5y /CareerLauncherMedia www.careerlauncher.com/upsc INDIA YEAR BOOK 2020 Contents 1.LAND AND THE PEOPLE .................................................................................................. 2 2. NATIONAL SYMBOLS ..................................................................................................... 6 3. POLITY .......................................................................................................................... 7 4. AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................. 20 5. CUTLURE AND TOURISM ............................................................................................. 23 6. BASIC ECONOMIC DATA .............................................................................................. 35 7. COMMERCE ................................................................................................................ 38 8. COMMUNICATION AND TECHNOLOGY ........................................................................ 42 9. DEFENSE ..................................................................................................................... 55 10. EDUCATION .............................................................................................................. 65 11. ENERGY ................................................................................................................... -

Rksk-Strategy-Handbook.Pdf

strategy handbook FIRST PUBLISHED: January 2014 Strategy Handbook Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi Acknowledgements The National Adolescent Health Strategy emerged out of a series of wide based consultations with diverse constituencies - academic and research organizations, domain experts, partner ministries, line departments, civil society organizations and youth collectives. It would not have been possible to bring out this strategy without their valuable and generous contribution. Secretary Health and Family Welfare, Mr Kesav Desiraju’s encouragement was our inspiration. Additional Secretary and Mission Director, NHM, Ms. Anuradha Gupta’s vision shaped the strategy. Her untiring guidance, vast experience steered the process and brought in new perspectives. Joint Secretary RCH, Dr Rakesh Kumar provided valuable insight and facilitated technical discussions which were critical for finalizing the strategy document. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), our partners in this endeavor provided technical support. Contributors from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Ms. Anuradha Gupta, Additional Secretary & Mission Director, NHM Dr. Rakesh Kumar, Joint Secretary, RCH Dr. Virender Singh Salhotra, Deputy Commissioner Dr. Sushma Dureja, Deputy Commissioner, Adolescent Health Ms. Anshu Mohan, Programme Manager, Adolescent Health Dr. Sheetal Rahi, Medical Officer, Adolescent Health UNFPA Team Ms. Frederika Meijer, Mr. Venkatesh Srinivasan, Mr. Rajat Ray, Dr. Dinesh Agarwal, Dr. Jaya, Dr. Sanjay Kumar, Dr. K.M. Sathyanarayana, Mr. Tej Ram Jat, Ms. Priyanka Ghosh, Dr. Anchita Patil, Mr. Rajat Khosla UNFPA Head Quarters and Regional Office: Ms. Kate Gilmore, Ms. Laura Laski, Ms. Lubna Baqi and Dr. Josephine Sauvarin Valuable feedback from the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), members of Technical Resource Group for Adolescent Health and members of Reference Group have strengthened the document. -

India Year Book 2018 Cover Latest

India Year Book (2018) Volume - II INDEX 1. Food and Civil Supplies ....... 01-07 2. Health and Family Welfare ....... 08-16 3. Housing ....... 17-22 4. Industry ....... 23-33 5. Law and Justice ....... 34-46 6. Labour, Skill Development and Employment ....... 47-54 7. Rural and Urban Development ....... 55-67 8. Scientific and Technological Developments ....... 68-78 9. Transport ....... 79-85 10. Water Resources ....... 86-92 11. Welfare ..... 93-107 12. Youth Affairs and Sports ... 108-116 13. Miscellaneous Content from Different Chapters ... 117-121 1 www.iasscore.in India Year Book (2018) Volume-II 1 Chapter FOOD AND CIVIL SUPPLIES The primary objective of the Department of Food and Public Distribution is to ensure food security for the country through: efficient procurement at Minimum Support Price (MSP), storage and distribution of food grains ensuring availability of food grains, sugar and edible oils through appropriate policy instruments; including maintenance of buffer stocks of food grains; making food grains accessible at reasonable prices, especially to the weaker and vulnerable sections of society under a Targeted Public Distribution System. Procurement of Food Grains Food Corporation of India (FCI), with the help of state government agencies, procures wheat, paddy and coarse grains in various states in order to provide price support to the farmers. Before each Rabi/ Kharif crop season, central government announces the Minimum Support Prices (MSP), based on the recommendations of Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), which takes into consideration the cost of various agricultural inputs and the reasonable margin for the farmers for their produce. With the substantial increase in production of food grains in recent years and with an emphasis on bringing Green Revolution in Eastern-India, the procurement operations have expanded to many states due to which accumulated Central Pool Stock of food grains had reached to a record level of 805.16 lakh tonnes in 2012 against the buffer norm of 319 lakh tonnes. -

Govt Schemes 2018- 19

GOVT SCHEMES 2018- 19 CONTENTS Ministry of Women and Child Development ............................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP) Scheme ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Aim .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Nodal Agency .................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Background ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 UP state women and child welfare department. ................................................................................................................................. 9 Kanya Sumangala Yojana ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 2. Pradhan Mantri Matritva Vandana Yojana ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Key Features Of The Scheme: