CRC/C/IND/3-4 Convention on the Rights of the Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Good Luck!

INDIA YEAR BOOK - 2017 INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Dear Students, With the focus on the provision of best study material to our students, Rau’s IAS Study Circle is innovatively presenting the voluminous INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 in a very concise and lucid manner. Through this, efforts have been taken to circulate the best synopsis extracted from the Year Book-2017 for the benefit of the students. The abstract has been designed to present contents of the year book in most user-friendly manner. All the major and important points are given in bold and highlighted. The content is also supported by figures and pictures as per the requirement. The content has been chosen and compiled judiciously so that maximum coverage of all the relevant and significant material is presented within minimum readable pages. The issue titled ‘INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 will be covering the following topics: 1. Land and the People 16. Health and Family Welfare 2. National Symbols 17. Housing 3. The Polity 18. India and the World 4. Agriculture 19. Industry 5. Culture and Tourism 20. Law and Justice 6. Basic Economic Data 21. Labour, Skill Development and Employment 7. Commerce 22. Mass Communication 8. Communications and Information Technology 23. Planning 9. Defence 24. Rural and Urban Development 10. Education 25. Scietific and Technological Developments 11. Energy 26. Transport 12. Environment 27. Water Resources 13. Finance 28. Welfare 14. Corporate Affairs 29. Youth Affairs and Sports 15. Food and Civil Supplies By providing this, the Study Circle hopes that all the students will be able to make the best use of it as a ready reference material and allay their fears of perusing and cramming the entire year book. -

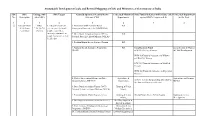

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of Csss and Ministries of Government of India

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. Description other SDGs Schemes (CSS) Departments against SDG's Targets (col. 4) in the State 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ① End poverty in SDGs 1.1 By 2030, eradicate 1. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural RD all its forms 2,3,4,5,6,7,8, extreme poverty for all Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) everywhere 10,11,13 people everywhere, currently measured as 2. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY) - RD people living on less than National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) $1.25 a day 3. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana - Gramin RD 4. National Social Assistance Programme RD Social Security Fund Social Secuity & Women (NSAP) SSW-03) Old Age Pension & Child Development. WCD-03)Financial Assistance to Widows and Destitute women SSW-04) Financial Assistance to Disabled Persons WCD-02) Financial Assistance to Dependent Children 5. Market Intervention Scheme and Price Agriculture & Agriculture and Farmers Support Scheme (MIS-PSS) Cooperation, AGR-31 Scheme for providing debt relief to Welfare the distressed farmers in the state 6. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY)- Housing & Urban National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM) Affairs, 7. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana -Urban Housing & Urban HG-04 Punjab Shehri Awaas Yojana Housing & Urban Affairs, Development 8. Development of Skills (Umbrella Scheme) Skill Development & Entrepreneurship, 9. Prime Minister Employment Generation Micro, Small and Programme (PMEGP) Medium Enterprises, 10. Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana Labour & Employment Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. -

India Review Special on Third India-U.S. Strategic Dialogue 2012

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. SPECIAL ON THIRD INDIA- U.S. STRATEGIC India DIALOGUE 2012 REVIEW New Delhi and Washington underscored the need to harness the full potential of A NEW their relationship during the third annual India-U.S. Strategic Dialogue. MOMENTUM (Photo: Jay Mandal/ On Assignment) India REVIEW A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. THIRD INDIA-US STRATEGIC DIALOGUE 2012 Conceptualization & Design: IANS Publishing 06 At Full Throttle... 08 Deciphering the Dialogue 10 ‘Affair of the Heart’ Recognizing that the India-U.S. relationship draws its strength and dynamism from the shared values and the growing links between the people of the two countries, New Delhi and Washington call for har- nessing the full potential of that relationship dur- ing the third annual India-U.S. Strategic Dialogue 16 From strategic cooperation to counter-terrorism, from trade and energy security to education and technology, the third annual Strategic Dialogue between India and the Future U.S. have led to several important advancements in their Trajectory strategic partnership INDIA-US STRATEGIC 3RD DIALOGUE 26 36 Converging Paths Meet the Catalyst 38 Injecting Faith 40 Securing 21st Century Ties 30 Addressing the 37th U.S.-India Business Council (USIBC) Leadership Summit, External Affairs Minister Cementing S.M. Krishna stressed that India would restore Ties investor confidence and regain economic momentum and growth 44 Open Government Platform 32 to Promote Transparency ‘Connect to India’ 45 Work force development, research in grand challenge areas like sustain- Knowledge Bearers able development, energy, public health and developing open educa- tion resources were some of the key areas discussed during the second 46 India-U.S. -

11-02 Am (The House Adjourned A

THURSDAY, THE 29TH MARCH, 2012 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) .11-02 a.m. (The House adjourned at 11-02 a.m. and re-assembled at 11-17 a.m.) 11-18 a.m. (The House adjourned at 11-18 a.m. and re-assembled at 12-00 Noon) 1. Starred Questions Answers to Starred Question Nos. 221 to 240 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 1706 to 1860 were laid on the Table. 3. Short Notice Question Answer to Short Notice Question No. 2 was laid on the Table. 12-00 Noon. 4. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Ajit Singh (Minister of Civil Aviation) laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following Notifications of the Ministry of Civil Aviation, along with delay statement, under Section 43 of the Airports Authority of India Act, 1994:— (1) No. AAI/PERS/EDPA/REG/2002, dated the 1st February, 2012, publishing the Airports Authority of India (Gratuity) Amendment Regulations, 2012. (2) S.O. 1859 (E), dated the 11th August, 2011, publishing the Airport Appellate Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 2011. Shri Vayalar Ravi (Minister of Overseas Indian Affairs) laid on the Table a copy (in English and Hindi) of the Outcome Budget, for the year 2012-13, in respect of the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs. From 11-00 a.m. to 11-02 a.m. some points were raised. From 11-17 a.m. to 11-18 a.m. some points were raised. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Child Welfare: a Critical Analysis of Some of the Socio-Legal Legislations in India

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 8, Ver. II (Aug. 2014), PP 54-60 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Child Welfare: A critical analysis of some of the socio-legal legislations in India Prof. Shilpa Khatri Babbar Sociology Professor at Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, Delhi (Affiliated to Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Delhi, India) Abstract: Children are a human resource, invaluable but vulnerable. It is very essential to enable their development in such a manner that they bloom with joy in an atmosphere of a caring society. Various social legislations in India, focusing on an environment for a full booming of this essential human resource have undergone a sea change: from a position where children were treated as non-entity and mere material objects to a position of human dignity where conscientious efforts have been made to not only make them free from exploitation and abuses but also enable them to develop their full potentiality with fair access to food, health, education and respect. This paper makes a critical analysis of the existent legislations on child labour, issues related to adoption and sexual abuse of children. Keywords: Adoption, Child Labour, Devadasis, Juvenile Justice, POCSO I. Introduction The Charter of Rights of Children (CRC) or the Geneva Declaration made by International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1924 was the first humanist effort to help their amelioration and to protect them against hazardous employment. Through a series of Recommendations and Conventions, the ILO had sensitized the public policy and influenced national policies especially against child labour. -

May 28, 2012 Dr. Manmohan Singh Honorable Prime Minister of India South Block, Raisina Hill New Delhi 110011 India +91-11-23

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor New York, NY 10118-3299 May 28, 2012 Tel: 212-290-4700 Fax: 212-736-1300 Fax: 917-591-3452 Dr. Manmohan Singh Honorable Prime Minister of India South Block, Raisina Hill WOMEN’S RIGHTS DIVISION New Delhi 110011 Liesl Gerntholtz, Executive Director Janet Walsh, Deputy Director India Nisha Varia, Senior Researcher Gauri van Gulik, Global Advocate +91-11-23019545 / +91-11-23016857 Meghan Rhoad, Researcher Aruna Kashyap, Researcher Agnes Odhiambo, Researcher Amanda Klasing, Researcher Dear Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh: Rumbie Chidoori, Associate Matthew Rullo, Associate We the undersigned organizations would like to urgently bring to ADVISORY COMMITTEE Betsy Karel, Chair your notice and reiterate our concerns about the treatment and care Pat Mitchell, Vice-Chair Karen Ackman given to women and children who experience sexual assault in light Mahnaz Afkhami Ellen Stone Belic of a series of disturbing news reports on this issue. Helen Bernstein Cynthia Brown David Brown Charlotte Bunch While on the one hand we acknowledge that the increasing numbers Ellen Chesler Rebecca Cook of news reports of sexual assault in the country could be indicative of Babeth Fribourg Adrienne Germain women’s improved ability to report the crime, what concerns us Marina Pinto Kaufman Hollis Kurman about these reports is that they consistently reveal the woefully poor Lenora Lapidus Stephen Lewis treatment meted out by state authorities to those who experience Lorraine Loder Joyce Mends-Cole such violence. Yolanda T. Moses Samuel K. Murumba Marysa Navarro-Aranguren Sylvia Neil One of the more recent and disturbing examples of this is the case of Martha C. -

Child Labour in Global Production Networks: Poverty, Vulnerability and ‘Adverse Incorporation’ in the Delhi Garments Sector

Working Paper June 2011 No. 177 Child labour in global production networks: poverty, vulnerability and ‘adverse incorporation’ in the Delhi garments sector Nicola Phillips Resmi Bhaskaran Dev Nathan C. Upendranadh What is Chronic Poverty? The distinguishing feature of chronic poverty is extended duration in University of Manchester absolute poverty. Manchester M13 0PL Therefore, chronically poor United Kingdom people always, or usually, live below a poverty line, Institute for Human Development (IHD) which is normally defined in terms of a money indicator New Delhi (e.g. consumption, income, India etc.), but could also be defined in terms of wider or subjective aspects of deprivation. This is different from the transitorily poor, who move in and out of poverty, or only occasionally fall below the poverty line. Chronic Poverty Research Centre www.chronicpoverty.org ISBN: 978-1-906433-79-6 Child labour in global production networks: poverty, vulnerability and ‘adverse incorporation’ in the Delhi garments sector Abstract Child labour occurs across many sectors of the Indian economy, including in those which are tightly integrated into global production networks (GPNs). On the basis of an original study of the Delhi garments sector, this paper explores the evolving relationship between the nature and functioning of GPNs, the incidence of highly exploitative social and labour relations (including those associated with child labour), and the production and reproduction of chronic poverty and vulnerability. Two questions frame the discussion: -

Hustling the State

Hustling the State Women’s Movements as Policy Entrepreneurs: Engaging the State in India Charu Bhaneja A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Charu Bhaneja (2014) ~ ii ~ Hustling the State Women’s Movements as Policy Entrepreneurs: Engaging the State in India Charu Bhaneja Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto « 2014 » Abstract This study examines the opportunities and constraints women activists confront as they pursue strategies to influence public policy in a fluctuating, diverse and complex political arena. To illustrate this, I suggest that engagement with the state can be efficacious in certain instances (violence against women) but that in those cases where women face structural constraints (women’s political representation), where the challenges are powerful, opportunity to have an impact is limited. Examining the extent to which the state has been an arena where women’s groups have been able to demand and achieve change provides significant insights into political environments that shape women’s agency and advocacy within that region. My doctoral thesis takes a multi-level approach in order to understand the impact of women’s movements on the state and its institutions. I maintain that women’s movement activity elicits state responsiveness and I analyze three factors to support my claim. First, I consider what government is in power and how open it is to engagement. Secondly, I consider how cohesive the women’s movement is on a particular issue and thirdly, I iii maintain that women’s national machinery can be an effective channel for implementing women’s interests. -

Urban Development in India: a Special Focus Public Finance Newsletter

Urban development in India: A special focus Public Finance Newsletter Issue XI March 2016 In this issue 2 Feature article 10 Pick of the quarter 20 Round the corner 22 Potpourri 24 PwC updates Knowledge is the only instrument of production that is not subject to diminishing returns. J M Clark Dear readers, ‘Round the corner’ provides news updates in the area of government finances and policies across the The above quotation from the globe and key paper releases in the public finance American economist still domain during the recent months, along with holds true. Knowledge reference links. The ‘Our work’ section presents a increases by sharing and our mid-term review of the Support Program for Urban initiative to share knowledge, Reforms (SPUR), Bihar, which was conducted by views and experiences in the our team for the Department for International public finance domain Development (DFID). SPUR is a six-year through this newsletter has given us returns in the programme being implemented by the Government form of readers and contributors from across the of Bihar in partnership with DFID in 29 urban local globe. In continuation with our efforts in this bodies of Bihar. direction, I welcome you to the eleventh issue of the Public Finance Newsletter. I would like to thank you for your overwhelming support and response. Your suggestions urge us to The feature article in this issue aims to delve continuously improve this newsletter to ensure deeper into India’s urban development agenda. effective information sharing. Last year, we witnessed the launch of new missions such as Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban We would like to invite you to contribute and share Transformation (AMRUT), which replaced the your experiences in the public finance space with Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission us. -

DECLINE and FALL of BUDDHISM (A Tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface

1 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Dr. K. Jamanadas 2 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface “In every country there are two catogories of peoples one ‘EXPLOITER’ who is winner hence rule that country and other one are ‘EXPLOITED’ or defeated oppressed commoners.If you want to know true history of any country then listen to oppressed commoners. In most of cases they just know only what exploiter wants to listen from them, but there always remains some philosophers, historians and leaders among them who know true history.They do not tell edited version of history like Exploiters because they have nothing to gain from those Editions.”…. SAMAYBUDDHA DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) By Dr. K. Jamanadas e- Publish by SAMAYBUDDHA MISHAN, Delhi DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM A tragedy in Ancient India By Dr. K. Jamanadas Published by BLUEMOON BOOKS S 201, Essel Mansion, 2286 87, Arya Samaj Road, Karol Baug, New Delhi 110 005 Rs. 400/ 3 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface Table of Contents 00 Author's Preface 01 Introduction: Various aspects of decline of Buddhism and its ultimate fall, are discussed in details, specially the Effects rather than Causes, from the "massical" view rather than "classical" view. 02 Techniques: of brahminic control of masses to impose Brahminism over the Buddhist masses. 03 Foreign Invasions: How decline of Buddhism caused the various foreign Invasions is explained right from Alexander to Md. -

Union Cabinet Minister, India.Pdf

India gk World gk Misc Q&A English IT Current Affairs TIH Uninon Cabinet Minister of India Sl No Portfolio Name Cabinet Minister 1 Prime Minister Minister of Atomic Energy Minister of Space Manmohan Singh Minister of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions Ministry of Planning 2 Minister of Finance P. Chidambaram 3 Minister of External Affairs Salman Khurshid 4 Minister of Home Affairs Sushil Kumar Shinde 5 Minister of Defence A. K. Antony 6 Minister of Agriculture Sharad Pawar Minister of Food Processing Industries 7 Minister of Communications and Information Technology Kapil Sibal Minister of Law and Justice 8 Minister of Human Resource Development Dr. Pallam Raju 9 Ministry of Mines Dinsha J. Patel 10 Minister of Civil Aviation Ajit Singh 11 Minister of Commerce and Industry Anand Sharma Minister of Textiles 12 Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas Veerappa Moily 13 Minister of Rural Development Jairam Ramesh 14 Minister of Culture Chandresh Kumari Katoch 15 Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation Ajay Maken 16 Minister of Water Resources Harish Rawat 17 Minister of Urban Development Kamal Nath Minister of Parliamentary Affairs 18 Minister of Overseas Indian Affairs Vayalar Ravi 19 Minister of Health and Family Welfare Ghulam Nabi Azad 20 Minister of Labour and Employment Mallikarjun Kharge 21 Minister of Road Transport and Highways Dr. C. P. Joshi Minister of Railway 22 Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises Praful Manoharbhai Patel 23 Minister of New and Renewable Energy Farooq Abdullah 24 Minister of Panchayati Raj Kishore Chandra Deo Minister of Tribal Affairs 25 Minister of Science and Technology Jaipal Reddy Minister of Earth Sciences 26 Ministry of Coal Prakash Jaiswal 27 Minister of Steel Beni Prasad Verma 28 Minister of Shipping G.