The Policy Environment for Food, Agriculture and Nutrition in India: Taking Stock and Looking Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Good Luck!

INDIA YEAR BOOK - 2017 INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Dear Students, With the focus on the provision of best study material to our students, Rau’s IAS Study Circle is innovatively presenting the voluminous INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 in a very concise and lucid manner. Through this, efforts have been taken to circulate the best synopsis extracted from the Year Book-2017 for the benefit of the students. The abstract has been designed to present contents of the year book in most user-friendly manner. All the major and important points are given in bold and highlighted. The content is also supported by figures and pictures as per the requirement. The content has been chosen and compiled judiciously so that maximum coverage of all the relevant and significant material is presented within minimum readable pages. The issue titled ‘INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 will be covering the following topics: 1. Land and the People 16. Health and Family Welfare 2. National Symbols 17. Housing 3. The Polity 18. India and the World 4. Agriculture 19. Industry 5. Culture and Tourism 20. Law and Justice 6. Basic Economic Data 21. Labour, Skill Development and Employment 7. Commerce 22. Mass Communication 8. Communications and Information Technology 23. Planning 9. Defence 24. Rural and Urban Development 10. Education 25. Scietific and Technological Developments 11. Energy 26. Transport 12. Environment 27. Water Resources 13. Finance 28. Welfare 14. Corporate Affairs 29. Youth Affairs and Sports 15. Food and Civil Supplies By providing this, the Study Circle hopes that all the students will be able to make the best use of it as a ready reference material and allay their fears of perusing and cramming the entire year book. -

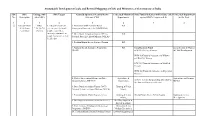

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of Csss and Ministries of Government of India

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. Description other SDGs Schemes (CSS) Departments against SDG's Targets (col. 4) in the State 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ① End poverty in SDGs 1.1 By 2030, eradicate 1. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural RD all its forms 2,3,4,5,6,7,8, extreme poverty for all Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) everywhere 10,11,13 people everywhere, currently measured as 2. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY) - RD people living on less than National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) $1.25 a day 3. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana - Gramin RD 4. National Social Assistance Programme RD Social Security Fund Social Secuity & Women (NSAP) SSW-03) Old Age Pension & Child Development. WCD-03)Financial Assistance to Widows and Destitute women SSW-04) Financial Assistance to Disabled Persons WCD-02) Financial Assistance to Dependent Children 5. Market Intervention Scheme and Price Agriculture & Agriculture and Farmers Support Scheme (MIS-PSS) Cooperation, AGR-31 Scheme for providing debt relief to Welfare the distressed farmers in the state 6. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY)- Housing & Urban National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM) Affairs, 7. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana -Urban Housing & Urban HG-04 Punjab Shehri Awaas Yojana Housing & Urban Affairs, Development 8. Development of Skills (Umbrella Scheme) Skill Development & Entrepreneurship, 9. Prime Minister Employment Generation Micro, Small and Programme (PMEGP) Medium Enterprises, 10. Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana Labour & Employment Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. -

Position Paper on SC & ST Final 6 May 05

Position Paper National Focus Group on Problems of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Children Introduction This position paper critically examines the contemporary reality of schooling of children belonging to Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities who have been historically excluded from formal education – the former due to their oppression under caste feudal society and the latter due to their spatial isolation and cultural difference and subsequent marginalisation by dominant society. There are thus sharp differences between these two categories of population in terms of socio-economic location and the nature of disabilities. However, there is also growing common ground today in terms of conditions of economic exploitation and social discrimination that arise out of the impact of iniquitous development process. Concomitantly, the categories themselves are far from homogenous in terms of class, region, religion and gender and what we face today is an intricately complex reality. Bearing this in mind this paper attempts to provide a contextualised understanding of the field situation of the education of SC/ST children and issues and problems that directly or indirectly have a bearing on their future educational prospects. The paper seeks to provide a background to the National Curriculum Framework Review being undertaken by the National Council of Educational Research and Training. As such, it looks critically and contextually at educational developments among the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe with a view to arrive at an understanding of what policy and programmatic applications can be made, especially in the domain of curriculum, to improve their situation. The problems are many and complex. The paper attempts but does not claim a comprehensive discussion of the varied nuances of their complexity. -

Nutrition Situation and Stakeholder Mapping

This report compiles secondary data on the nutrition situation and from a stakeholder mapping in Pune, India to inform the new partnership between Birmingham, UK and Pune on Smart Nutrition Pune Nutrition situation and Courtney Scott, The Food Foundation) stakeholder mapping 2018 Table of Contents About BINDI ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Nutrition Situational Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 3 Malnutrition in all its forms ............................................................................................................................ 3 Causes of malnutrition in Pune ..................................................................................................................... 6 Current Public Health / Food Interventions ................................................................................................... -

Mid Day Meal Scheme in Himachal Pradesh

Mid Day Meal Scheme in Himachal Pradesh Economics 8t Statistics Department Himachal Prabesh Evaluation of Mid Day Meal Scheme in Himachal Pradesh Economics & Statistics Department Himachal Pradesh prtucalional Plann/, documentation Ce^ Pradeep Chauhan Economic Adviser Government of Himachal Pradesh PREFACE Indian education system is suffering enrolment, dropout and retention at primary and secondary level. In view of this issue, the Government of India has launched the scheme titled as Mid-Day Meal through which the benefits were targeted to the vulnerable section of the society i.e. the future of the country. This programme has also been introduced in the State in the same perspective. Since there is no data from the studies on the technical, operational and administrative feasibility of MDM implementation in the state, it was considered imperative to carry out mid-term evaluation as per guideline of Government of Himachal to determine the effectiveness, outcome and impact of the scheme. The evaluation study was conducted in six selected district Chamba, Kullu, L & S, Mandi and Sirmaur. The Present report is based on the data collected, analyzed from sample of 334 MDM centres which comprised in 33 Blocks of State. The Mid Day Meal scheme in HP is monitored by the Department of Education and this evaluation study was carried out by Department of Economics and Statistics. The main findings of the survey are present in Executive Summary of the report. The department acknowledges, with gratitude the unstinted co operation received from the students, local people and teachers and thanks to the authorities of education department, but for whose co operation, the survey would not have been possible. -

REPORT of CENTRE for DEVELOPMENT STUDIES on MID DAY MEALS in SCHOOLS DURING the PERIOD of 1St October, 2014 to 31St March, 2015

THIRD HALF YEARLY MONITORING REPORT OF CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ON MID DAY MEALS IN SCHOOLS DURING THE PERIOD OF 1st October, 2014 to 31st March, 2015 Districts Monitored/Covered 1. Kannur 2. Idukki 3. Palakkad 4. Wayanad 5. Kozhicode Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala 1 INDEX Sl.No. Particulars/Details Page No. 1. Forward 3 2. Acknowledgement 4 3. General Information 5 4 Detailed Report on Kannur District 7 5. Detailed Report on Idukki District 25 6. Detailed Report on Palakkad District 41 7. Detailed Report on Wayanad District 58 8. Detailed Report on Kozhicode District 75 2 FOREWORD Centre for Development Studies, the Monitoring Institute in charge of monitoring all districts (fourteen) in Kerala state feels privileged to be one of the Monitoring Institutions across the country for broad based monitoring of SSA, RTE and MDM activities. This is the third half yearly report on Mid Day Meals (MDM) for the year 2013-15 and is based on the data collected from five districts in Kerala, viz., Kannur, Idukki, Palakkad, Wayanad and Kozhicode. I hope the findings of the report would be helpful to both the Government of India and the Government of Kerala state to understand the functioning of and the achievements with regard to Mid Day Meals (MDM) in the state. The problems identified at the grass root level may be useful for initiating further interventions in the implementation of Mid Day Meals (MDM) in the state. In this context I extend my hearty thanks to C. Gasper, Nodal Officer for monitoring Mid Day Meals (MDM) in Kerala and his team members who have rendered a good service by taking pains to visit the schools located in the most inaccessible areas and preparing the report in time. -

Csap-At-15-03-2021

THE ASSAM TRIBUNE ANALYSIS DATE – 15 MARCH 2021 For Preliminary and Mains examination As per new Pattern of APSC (Also useful for UPSC and other State level government examinations) Answers of MCQs of 13-03-2021 1. C 2. D. Shanghai, China 3. B. Johannesburg, South Africa 4. D. 2010 5. B. Amrita Pritam MCQs of 15-03-2021 Q1. India is a member of which among the following? 1. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation 2. Association of South-East Asian Nations 3. East Asia Summit Select the correct answer using the code given below. A. 1 and 2 only B. 3 only C. 1, 2 and 3 D. India is a member of none of them Q2. The term ‘Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’ often appears in the news in the context of the affairs of a group of countries known as A. G20 B. ASEAN C. SCO D. SAARC Q3. India is a regular member of which of the following organizations? 1. BIMSTEC 2. Shanghai Cooperation Organization 3. ASEAN 4. G-20 Codes: A. 1 and 2 only B. 2 and 3 only C. 1 and 4 only D. All of these Q4. UDAN scheme launched in the year A. 2015 B. 2016 C. 2017 D. 2018 Q5. The proportion of tribal population to the total population of Assam is A. One third B. One fifth C. One – eighth D. One – tenth CONTENTS 1. Committed to free, secure and ‘prosperous Indo-Pacific region’ ( GS 2 – International Relations ) 2. Govt launches UDAN 4.1, invites bids for priority routes ( GS 3 – Schemes ) 3. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Background Papers and Notes Commissioned for IPPR 2014 Chander, Parkash. ‘A Note on Price Subsidies and Direct Cash Transfers’. Dev, Mahendra S. ‘Food Security with Focus on Nutrition in India – Performance and Polices’. Goyal, Yugank. ‘India’s Public Distribution System: What has Gone Wrong?’ Iversen, Vegard. ‘Mending the (which ‘skill’?) Gaps – Training Options and Returns in Markets for Low and Unskilled Jobs’. Kapoor, Rakesh, Kathpalia, G.N. and Kapoor, Aditi. ‘Natural Resources Management and Related Challenges for Eradication of Malnutrition and Poverty’. Nakray, Keerty. ‘Child Poverty and Wellbeing: Ecological Contexts of Deprivation and Social Policy in India’. Pratap, K.V. ‘A Note on Issues in Public-Private Partnerships: Road and Power Sector’. Kumar, C. Raj. ‘A Note on Rule of Law and Democratic Governance in India’. Raman, Bhuvaneshwari. ‘Influence of Urban Development and Land Policies on Poverty’. Sen, Sarbani. ‘Public Interest Litigation in India’. Sinha, Samrat. ‘Food, Nutrition and Livelihood Security in Conflict and Post-Conflict Situations – Some Lessons from 2012 ‘BTAD Humanitarian Crisis’’. Viswanathan, Brinda. ‘Undernutrition in India – Evidence and Intervention’. Tripathy, Damodar. ‘Odisha – Growth, Malnutrition and Hunger’. BIBLIOGRAPHY 241 Other Reference Works Aakella, K.V. and Kidambi, S. 2007. ‘Challenging Corruption with Social Audits’, Economic and Political Weekly, 3 February. Acemoglu, Daron and Robinson, James A. (2012) Why Nations Fail: the Origin of Power, Prosperity and Poverty, New York: Crown Business. Alkire, S. and Foster, J. 2010. ‘Designing the Inequality – Adjusted Human Development Index’, OPHI Working paper No.37, Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. Banerjee, A. and Dufflo, E. 2011.Poor Economics: Rethinking Poverty and the Ways to End It, Random House, India. -

Introduction to Government Schemes

INTRODUCTION TO GOVERNMENT SCHEMES Restructuring of Government Schemes: NITI Aayog appointed a Sub Group of Chief Ministers on Rationalisation of Centrally Sponsored Schemes under the Chairmanship of CM of MP for the restructuring of Centrally Government Schemes. Recommendations of the sub-group are: • Number of Schemes: The total number of Centrally Sponsored Schemes should not exceed 30. • Categorisation of Schemes: Existing CSSs should be divided into Core and Optional Schemes. ο Core schemes: Focus of CSSs should be on schemes that comprise the National Development Agenda where the Centre and States will work together in the spirit of Team India. ο Core of the Core Schemes: Those schemes which are for social protection and social inclusion should form the core of core and be the first charge on available funds for the National Development Agenda. ο Optional Schemes: The Schemes where States would be free to choose the ones they wish to implement. Funds for these schemes would be allocated to States by the Ministry of Finance as a lump sum. • Funding Pattern: ο Core of Core Schemes: Existing funding pattern of the core of core schemes would continue. ο Core Schemes: . For 8 North Eastern States and 3 Himalayan States: Centre: State: 90:10 . For other States: Centre: State: 60:40 . For Union Territories (without Legislature): Centre 100% and for UTs with legislature existing funding pattern would continue. ο Optional Schemes: a) For 8 North Eastern States and 3 Himalayan States: Centre: State: 80:20 b) For other States: Centre: State: 50:50 c) For Union Territories: (i) (without Legislature) - Centre 100% (ii) Union Territories with Legislature: Centre: UT:80:20. -

Parliament of India Rajya Sabha Parliament

PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi December, 2016/Agrahayana, 1938 (Saka) Hindi version of this publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT TWO HUNDRED EIGHTY THIRD REPORT The Implementation of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan And Mid-Day-Meal Scheme (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 15th December, 2016) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 15th December, 2016) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi December, 2016/ Agrahayana, 1938 (Saka) C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE …........................................................... (i) 2. PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………. (ii) 3. LIST OF ACRONYMS ……….......…............................................................ (iii)-(iv) 4. REPORT.........................................................................................…... ......................... 4. *OBSERVATIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE - AT A GLANCE ... 5. *MINUTES .............................................................................................. 6. *ANNEXURES.................................................................................................. ______________________________ *Appended on printing stage COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (Constituted w.e.f. 1st September, 2016) 1. Dr. Satyanarayan Jatiya ¾ Chairman RAJYA SABHA 2. Prof. Jogen Chowdhury 3. Prof. M.V. Rajeev Gowda 4. Shri -

Community Development

The ability of governments to achieve their social and economic goals with limited resources is dependent upon efficiency, transparency and flexibility of public administration institutions. Even though economic advancement is witnessed worldwide, certain economies are marked with a very interesting paradox - accelerated economic progress on one hand, and extreme social and economic inequality, particularly for women, girls, and marginalised and vulnerable groups on the other, including those who are living with disability. Gender equality and social inclusion objectives and approaches are therefore critical to achieving long-term development goals that significantly improve the lives of the world’s poorest people. Community We work in partnership with development agencies, governments and NGOs to create solutions for achieving inclusive and sustainable community development. We have successfully designed and implemented multi- Development faceted development interventions that have integrated gender equality and social inclusion as cross cutting issues in all aspects of social and economic programming including private sector development, urban planning and development, slum development and community empowerment. We are skilled in policy development, capacity building, participatory approaches, adaptive management, community mobilisation, voice and accountability, behaviour change communication, design of social safety nets, beneficiary feedback analysis, satisfaction surveys, poverty assessments and monitoring approaches and results -

Urban Development in India: a Special Focus Public Finance Newsletter

Urban development in India: A special focus Public Finance Newsletter Issue XI March 2016 In this issue 2 Feature article 10 Pick of the quarter 20 Round the corner 22 Potpourri 24 PwC updates Knowledge is the only instrument of production that is not subject to diminishing returns. J M Clark Dear readers, ‘Round the corner’ provides news updates in the area of government finances and policies across the The above quotation from the globe and key paper releases in the public finance American economist still domain during the recent months, along with holds true. Knowledge reference links. The ‘Our work’ section presents a increases by sharing and our mid-term review of the Support Program for Urban initiative to share knowledge, Reforms (SPUR), Bihar, which was conducted by views and experiences in the our team for the Department for International public finance domain Development (DFID). SPUR is a six-year through this newsletter has given us returns in the programme being implemented by the Government form of readers and contributors from across the of Bihar in partnership with DFID in 29 urban local globe. In continuation with our efforts in this bodies of Bihar. direction, I welcome you to the eleventh issue of the Public Finance Newsletter. I would like to thank you for your overwhelming support and response. Your suggestions urge us to The feature article in this issue aims to delve continuously improve this newsletter to ensure deeper into India’s urban development agenda. effective information sharing. Last year, we witnessed the launch of new missions such as Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban We would like to invite you to contribute and share Transformation (AMRUT), which replaced the your experiences in the public finance space with Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission us.