Barbara Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the First Comprehensive Treatment of Oldenburg's

No. 56 V»< May 31, 1970 he Museum of Modern Art FOR IMT4EDIATE RELEASE jVest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart (N.B. Publication date of book: September 8) CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the first comprehensive treatment of Oldenburg's life and art, will be published by The Museum of Modern Art on September 8, 1970. Richly illustrated with 224 illustrations in black-and-white and 52 in color, this monograph, which will retail at $25, has a highly tactile., flexible binding of vinyl over foam-rubber padding, making it a "soft" book suggestive of the artist's well- known "soft" sculptures. Oldenburg came to New York from Chicago in 1956 and settled on the Lower East Side, at that time a center for young artists whose rebellion against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and search for an art more directly related to their urban environment led to Pop Art. Oldenburg himself has been regarded as perhaps the most interesting artist to emerge from that movement — "interesting because he transcends it," in the words of Hilton Kramer, art critic of the New York Times. As Miss Rose points out, however, Oldenburg's art cannot be defined by the label of any one movement. His imagination links him with the Surrealists, his pragmatic thought with such American philosophers as Henry James and John Dewey, his handling of paint in his early Store reliefs with the Abstract Expressionists, his subject matter with Pop Art, and some of his severely geometric, serial forms with the Mini malists. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Draft July 6, 2011

Reinhardt, Martin, Richter: Colour in the Grid of Contemporary Painting by Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History, Department of Art in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada Final submission, September, 2011 Copyright ©Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt, 2011 Abstract The objective of my thesis is to extend the scholarship on colour in painting by focusing on how it is employed within the structuring framework of the orthogonal grid in the paintings of three contemporary artists, Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin and Gerhard Richter. Form and colour are essential elements in painting, and within the ―essentialist‖ grid painting, the presence and function of colour have not received the full discussion they deserve. Structuralist, post-structuralist and anthropological modes of critical analysis in the latter part of the twentieth century, framed by postwar disillusionment and skepticism, have contributed to the effective foreclosure of examination of metaphysical, spiritual and utopian dimensions promised by the grid and its colour earlier in the century. Artists working with the grid have explored, and continue to explore the same eternally vexing problems and mysteries of our existence, but analyses of their art are cloaked in an atmosphere and language of rationalism. Critics and scholars have devoted their attention to discussing the properties of form, giving the behavior and status of colour, as a property affecting mind and body, little mention. The position of colour deserves to be re-dressed, so that we may have a more complete understanding of grid painting as a discrete kind of abstract painting. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find e good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

BARBARA ROSE P.,

The Museum of Modern Art No. 78 BARBARA ROSE p., .. „ Public information Barbara Rose organized LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she is Consulting Curator, and collaborated in its installation at The Museum of Modern Art. She received a B.A. from Barnard College and a Ph.D. in the History of Art from Columbia University. In 1961- 62, she was a Fulbright Fellow to Spain. She has taught at Yale University; Sarah Lawrence and Hunter Colleges; the University of California, Irvine; and was Regent's Professor at the University of California, San Diego. A prominent critic of contemporary art, Miss Rose is currently an associate editor of Arts Magazine and Partisan Review. She was formerly New York correspondent for Art International and a contributing editor to Artforum and Art in America. Her writings have twice received the College Art Associa tion Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinguished Art Criticism. Miss Rose has curated and co-curated many exhibitions, including Claes Oldenburg (1969); Patrick Henry Bruce - An American Modernist (1980); Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock: A Working Relationship (1980); and Miro in America (1982). She has recently co-authored the exhibition catalogues Leger and the Modern Spirit (1982) and Goya: The "Disasters of War" and Selected Prints from the Collection of the Arthur Roth Foundation (1984). In addition to the catalogue accompanying LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE, Miss Rose is the author and editor of American Painting, American Art Since 1900, Readings in American Art, and several monographs. She has also made films on American artists, among them North Star: Mark di Suvero, Sculptor, and Lee Krasner: The Long View, a Cine Film Festival Gold Eagle Recipient in 1980. -

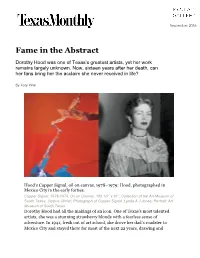

Fame in the Abstract

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs. -

Minimalism and Postminimalism

M i n i m a l i s m a n d P o s t m i n i m a l i s m : t h e o r i e s a n d r e p e r c u s s i o n s Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism 4372 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago David Getsy, Instructor [[email protected]] Spring 2000 / Tuesdays 9 am - 12 pm / Champlain 319 c o u r s e de s c r i pt i o n Providing an in-depth investigation into the innovations in art theory and practice commonly known as “Minimalism” and “Postminimalism,” the course follows the development of Minimal stylehood and tracks its far-reaching implications. Throughout, the greater emphasis on the viewer’s contribution to the aesthetic encounter, the transformation of the role of the artist, and the expanded definition of art will be examined. Close evaluations of primary texts and art objects will form the basis for a discussion. • • • m e t h o d o f e va l u a t i o n Students will be evaluated primarily on attendance, preparation, and class discussion. All students are expected to attend class meetings with the required readings completed. There will be two writing assignments: (1) a short paper on a relevant artwork in a Chicago collection or public space due on 28 March 2000 and (2) an in- class final examination to be held on 9 May 2000. The examination will be based primarily on the readings and class discussions. -

Oral History Interview with Leo Castelli, 1969 July

Oral history interview with Leo Castelli, 1969 July Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Leo Castelli in July, 1969. The interview took place in New York, N.Y., and was conducted by Barbara Rose for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. In 2016, staff at the Archives of American Art reviewed this transcript to make corrections. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview BARBARA ROSE: You said that you first became involved in art in a gallery in Paris. Could you tell me something about that gallery? LEO CASTELLI: I started that gallery with Rene Drouins in 1939. We had just one show I believe. And the artists that we were, at the time, involved with were the Surrealists: Max Ernst, Leonor Fini, Tchelitchew, Dali and some other minor ones, or not so minor really. But, for instance, Meret Oppenheim whose fame rests chiefly on the fur cup— BARBARA ROSE: What was your first contact with the New York art world? LEO CASTELLI: Well, the New York art world I really contacted when I got here in 1941 after the outbreak of the war. My first contact was with Julien Levy who was handling the Surrealists. BARBARA ROSE: Was his the most active gallery? LEO CASTELLI: He was the gallery that was active here in that particular field. There was also - I didn't know him at the time—but Pierre Matisse was in existence. -

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns's Paintings in The

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns’s Paintings in the Context of Postwar American Art by Ela Krieger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Approved Dissertation Committee Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche Jacobs University Bremen Prof. Dr. Paul Crowther Alma Mater Europaea Ljubljana Dr. Julia Timpe Jacobs University Bremen Date of Defense: 5 June 2019 Social Sciences and Humanities Abstract Abstract From the beginning of his artistic career, American artist Jasper Johns (b. 1930) has used various repetitive means in his paintings. Their significance in his work has not been sufficiently discussed; hence this thesis is an exploration of the role and the nature of repetition in Johns’s paintings, which is essential to better understand his artistic production. Following a thorough review of his paintings, it is possible to broadly classify his use of repetition into three types: repeating images and gestures, using the logic of printing, and quoting and returning to past artists. I examine each of these in relation to three major art theory elements: abstraction, autonomy, and originality. When Johns repeats images and gestures, he also reconsiders abstraction in painting; using the logic of printing enables him to follow the logic of another medium and to challenge the autonomy of painting; by quoting other artists, Johns is reexamining originality in painting. These types of repetition are distinct in their features but complementary in their mission to expand the boundaries of painting. The proposed classification system enables a better understanding of the role and the nature of repetition in the specific case of Johns’s paintings, and it enriches our understanding of the use of repetition and its perception in art in general. -

Abstract Illusionism: Taking the Realism out of Illusion

James Havard, Flat Head River, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96 inches. Louis K. Meisel Gallery. Abstract Illusionism: Taking the Realism out of Illusion Cassidy Garhart Velazquez Colorado State University ART695A Specialization Research Project Fall 2007 Figure 1 : Ronald Davis, Disk, 1968, Figure 2: Paul Sarkisian, Untitled #12, 1980 Figure 3: James Havard, Cafe Rico, 1979, moulded polyester resin and fiberglass, 62 acrylic, silkscreen, & glitter on canvas, 46 acrylic on canvas, 20 x 30 inches. x 132 inches, Dodecagon series. x 48 inches. "When the illusion is lost, art is hard to find." The work of the artists dubbed Abstract Illusionists heroically dealt with so many painting issues. Sometimes the beauty and lyrical painterly qualities of their work is overshadowed (to the untrained eye) as the observer unravels the visual complexities involved in the abstract depiction of space. Dimension always exists in abstraction, no matter how it may be concealed. It is the ironic honesty of Abstract Illusionism that ranks it among the great "isms" of twentieth century painting. I Andrea Marzell Los Angeles, California 1Posted to the abstract-art.com guest book in 1997. The www.abstract-art.com web page was founded and is maintained by Ronald Davis. 1 In September of 1976 the Paul Mellon Arts Center in Wallingford, Connecticut held the first "official" group exhibition of Abstract Illusionist paintings. 1 The show was organized by Louis K. Meisel who, together with Ivan Karp, coined the phrase "Abstract Illusionism".2 Meisel extends credit to Karp (owner of the O.K. Harris gallery) saying that Karp was the first to refer to the style as "illusionistic abstraction", but, in Meisel' s words, his own phrase "abstract illusionism" is the one that "stuck". -

STEPHEN ANTONAKOS Laconia, Greece 1926 — New York 2013

STEPHEN ANTONAKOS Laconia, Greece 1926 — New York 2013 Antonakos’s work with neon since 1960 has lent the medium new perceptual and formal meanings in hundreds of gallery and museum exhibitions first in New York and then internationally. His use of spare, complete and incomplete geometric neon forms has ranged from direct 3-D indoor installations to painted Canvases, Walls, the well known back- lit Panels with painted or gold surfaces, his Rooms and Chapels. Starting in the 1970s he installed over 55 architecturally-scaled permanent Public Works in the USA, Europe, Israel, and Japan. Throughout, he conceived work in relation to its site — its scale, proportions, and character — and to the space that it shares with the viewer. He called his art, “real things in real spaces,” intending it to be seen without reference to anything outside the immediate visual and kinetic experience. Colored pencil drawings on paper and vellum, often in series, have been a major, rich practice since the 1950s; as has his extensive work with collage. Other major practices include the conceptual Packages, small-edition Artist’s Books, silver and white Reliefs, prints, and — since 2011 — several series of framed and 3-D Gold Works. Antonakos was born in the small Greek village of Agios Nikolaos in 1926 and moved to New York with his family in 1930. In the late 1940s, after returning from the US Army, he established his first studio in New York’s fur district. From the early 1960s forward, until the end in 2013, he worked in studios in Soho. EXHIBITIONS 2018 to 2019 “Antonakos: The Room Chapel” Curated by Elaine Mehelakes — Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, PA, May 6, 2018 - May 5, 2019 2018 “Antonakos: Proscenium” Curated by Helaine Posner — Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY Purchase, NY, Jan. -

150 a Tremendous Success").2

150 FIG.4.1 Installation view, Don Judd, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 27 FebruarY-24 March 1968 Curator, William C. Agee THE OPENING OF OONALD JUDD'S solo exhibition at catalogue raisonn. designation Untitled rOSS 79] [fig. 4.3]), the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968 sealed his "As an object, the box was very much there ... Its. whole reputation as a central figure in contemporary art. William purpose seemed to be the declaration of some blunt quid C. Agee, the curator, had packed Judd's sheet-metal sculp dityand nothing more."'ln the years since, Judd's works tures fairly tightly into what at least one critic described as have likewise appeared "blunt, unambiguous," "completely a warehouselike installation,and the tidy right angles and present," "just existing," and "simply 'there.' "5 Each sculp repetitive modularity of the works made a neat match to ture has asserted itself as· "simply another thing in the world the stone tiles and concrete ceUing coffers of the museum's of things."'ln the 1967 essay "Art andObjecthood," which two-year-old Marcel Breuer building (fig. 4.1).' Sitting remains the single most influential account of Minimalism, brightly in the middle of the space, Untitled (OSS 128) (fig. Michael Fried characterized Judd's work (together with that 4.2) exemplified the overall appearance of the exhibition: of Robert Morris and others) as a "literalist art" that insisted a shiny rectangle of amber Plexiglas with a thin and hollow on its own occupation of ordinary space and time? By the stainless.-steel core.