TELL ME a STORY: NARRATIVE and ORALITY in NINETEETH-CENTURY AMERICAN VISUAL CULTURE by Catherine H. Walsh a Dissertation Submit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superfine UNSETTLED Pr 10.15.18

t r a n s f o r m e r FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Victoria Reis/Georgie Payne October 15, 2018 202.483.1102 or [email protected] Transformer presents: UNSETTLED - An Afternoon of Performance Art Saturday, November 3, 2018, 3-7pm At Superfine! The Fair Union Market, Dock 5 Event Space 1309 5th Street Northeast, Washington, DC Transformer is pleased to present UNSETTLED – a performance art series curated for Superfine! The Fair by Victoria Reis, Founder and Director of Transformer. UNSETTLED features performances by a select group of leading DC based emerging artists – Hoesy Corona, Rex Delafkaran, Maps Glover, Kunj, and Tsedaye Makonnen – each of whom are pushing performance art forward with their innovative, interdisciplinary work. Previously presented in Miami and New York, with upcoming manifestations in Los Angeles, Superfine! The Fair – created in 2015 by James Miille, an artist, and Alex Mitow, an arts entrepreneur – makes its DC premiere October 31 to November 4, 2018 at Union Market’s Dock 5 event space, featuring 300 visual artists from DC and beyond who will present new contemporary artwork throughout 70+ curated booths. Superfine! also features emerging collector events, tours, film screenings and panels. https://superfine.world/ Always seeking new platforms to connect & promote DC based emerging artists with their peers and supporters, and new opportunities to increase dialogue among audiences about innovative contemporary art practices, Transformer is excited to present UNSETTLED at Superfine! UNSETTLED curator and Executive & Artistic Director of Transformer Victoria Reis states: “Superfine! at Union Market’s Dock 5 presents an opportunity for Transformer to advance our partnership based mission, expand our network, and further engage with a growing new demographic of DC art collectors and contemporary art enthusiasts. -

Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…The Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018

CACI’s annual Convention July 8‐14, 2018 Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…the Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018 *As published by Travel+Leisure, www.travelandleisure.com, July 26, 2017. Panorama of the Baltimore Harbor Baltimore has 66 National Register Historic Districts and 33 local historic districts. Over 65,000 properties in Baltimore are designated historic buildings in the National Register of Historic Places, more than any other U.S. city. Baltimore - first Catholic Diocese (1789) and Archdiocese (1808) in the United States, with the first Bishop (and Archbishop) John Carroll; the first seminary (1791 – St Mary’s Seminary) and Cathedral (begun in 1806, and now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - a National Historic Landmark). O! Say can you see… Home of Fort McHenry and the Star Spangled Banner A monumental city - more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country Harborplace – Crabs - National Aquarium – Maryland Science Center – Theater, Arts, Museums Birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe, Babe Ruth – Orioles baseball Our hotel is the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor For exploring Charm City, you couldn’t find a better location than the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor. A stone’s throw from the water, it gets high points for its proximity to the sights, a rooftop pool and spacious rooms. The 14- story glass façade is one of the most eye-catching in the area. The breathtaking lobby has a tilted wall of windows letting in the sunlight. -

2003 Annual Report of the Walters Art Museum

THE YEAR IN REVIEWTHE WALTERS ART MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 France, France, Ms.M.638, folio 23 verso, 1244–1254, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York Dear Friends: After more than three intense years renovating and reinstalling our Centre Street Building, which con- cluded in June 2002 with the opening of our transformed 19th-century galleries, we stepped back in fiscal year 2002–2003 to refocus attention on our Charles Street Building, with its Renaissance, baroque, and rococo collections, in preparation for its complete reinstallation for a fall 2005 opening. For the Walters, as for cultural institutions nationwide, this was more generally a time of reflection and retrenchment in the wake of lingering uncertainty after the terrorist attack of 9/11, the general economic downturn, and significant loss of public funds. Nevertheless, thanks to Mellon Foundation funding, we were able to make three new mid-level curatorial hires, in the departments of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance and baroque art. Those three endowed positions will have lasting impact on the museum, as will a major addition to our galleries: in September 2002, we opened a comprehensive display of the arts of the ancient Americas, thanks to a long-term loan from the Austen-Stokes Foundation. Now, for the first time, we are able to expand on a collecting area Henry Walters entered nearly a century ago, to match our renowned ancient and medieval holdings in quality and range with more than four millennia of works from the western hemisphere. The 2002–2003 season was marked by three major exhibitions organized by the Walters, and by the continued international tour of a fourth Walters show, Desire and Devotion. -

The Walters Art Museum Summer Art Adventures 2020 Overview

The Walters Art Museum Summer Art Adventures 2020 Overview: The Walters Art Museum is excited to offer FREE Summer Art Adventures: Museum at Home Edition. All activities are geared toward children ages 6 to 11. Art Kits include art supplies and an activity packet with images from the Walters’ collection, a scavenger hunt, coloring page, and directions for an art project. These limited-edition kits are available in English and Spanish and will be distributed in August at Baltimore City Public Schools Emergency Distribution Sites. Summer Art Adventures also includes live virtual workshops led by Walters educators on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays from July 20-August 14; art-making videos; and downloadable activity packets. All of these free resources are available at https://thewalters.org/experience/virtual/summer/. Notes for Art Kit distribution site staff: ● All packets are in English and Spanish, so families don’t need to choose one or the other. ● At the end of the packet there’s an email address to share photos of children’s artwork with the Walters. We’ll add it to our online gallery and share via social media. Please include first name and age if you would like your photos shared! ● At the end of the packet there’s also a url for a short survey. We would greatly appreciate feedback if families have internet access (can be completed on a phone!). ● Each distribution site will get 1 of 4 different art projects. Families can access the other 3 art projects, as well as videos with more art-making activities, on the Walters website: https://thewalters.org/experience/virtual/summer/ (they’ll just need to procure their own art supplies, some of which families may have around the house). -

Christmas Stamp Features Walters Art Museum Treasure by Raphael

Christmas stamp features Walters Art Museum treasure by Raphael By George P. Matysek Jr. [email protected] A Raphael masterpiece that hangs in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore is getting national attention this holiday season as the U.S. Postal Service features the “Madonna of the Candelabra” as one of its 2011 Christmas stamps. The circular oil painting, created by the famed Renaissance artist circa 1513, shows a serene Blessed Virgin Mary holding the child Jesus. It was purchased by Henry Walters from a Vatican official in 1900, becoming the first Raphael Madonna to enter the United States. Joaneath Spicer, curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters, said the painting is especially notable for the way it combines an idealized image of Mary with a very human Jesus. Standing in front of the masterwork, Spicer pointed out that the child Jesus places a hand on his mother’s chest and exhibits a bit of mischief on his face. “You have the Christ child saying, ‘You know, it’s almost lunch time,’ “ Spicer said with a laugh. “You have that little bit of humor in there to emphasize Christ’s humanity. This is a real kid. He’s a baby and he needed to eat to grow just as a human baby does.” Mary’s gesture also touches on humanity, Spicer said, as she lovingly rests her hand on her child’s torso. “It’s wonderful the sense of touch that’s brought out,” she said. “The little Christ child is being comforted.” Contemporaries of Raphael such as Leonardo and Michelangelo tended to be more cerebral in their paintings, Spicer said. -

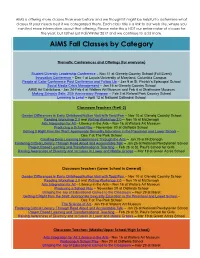

AIMS Fall Classes by Category

AIMS is offering more classes than ever before and we thought it might be helpful to determine what classes fit your needs best if we categorized them. Each class title is a link to our web site, where you can find more information about that offering. Please note this is NOT our entire roster of classes for the year, but rather just Fall/Winter 2017 and we continue to add more. AIMS Fall Classes by Category Thematic Conferences and Offerings (for everyone) Student Diversity Leadership Conference – Nov 11 at Glenelg Country School (Full Event) Innovation Conference – Dec 1 at Loyola University of Maryland, Columbia Campus People of Color Conference Post Conference and Follow Up – Jan 9 at St. Patrick’s Episcopal School Social Media Crisis Management -- Jan 16 at Glenelg Country School AIMS Art Exhibitions - Jan 24-Feb 4 at Walters Art Museum and Feb 4 at Strathmore Museum Making Schools Safe: 20th Anniversary Program -- Feb 2 at Roland Park Country School Learning to Lead -- April 12 at National Cathedral School Classroom Teachers (PreK-2) Gender Differences in Early Childhood/Author Visit with Todd Parr – Nov 10 at Glenelg Country School Reading Workshop 2.0 and Writing Workshop 2.0 -- Nov 15 at McDonogh Arts Integration for All – Literacy in the Arts – Nov 16 at Walters Art Museum Producing a School Play – November 20 at Oldfields School Getting It Right from the Start: Appropriate Sexuality Education in the Preschool and Lower School – Dec 7 at The Park School Creating Deep Learning Experiences Through the Arts -- Jan 25 at McDonogh Fostering Critical Literacy Through Read Aloud and Accountable Talk -- Jan 26 at National Presbyterian School Project Based Learning and Transformational Teaching -- Feb 28 at St. -

The Chemistry-Biology Interface (CBI) Graduate Program

About JHU Contact The Chemistry-Biology Johns Hopkins University was the first American Chemistry-Biology Interface Graduate Program institution to offer and emphasize graduate Department of Chemistry education. Throughout the years, the name Johns Johns Hopkins University Interface (CBI) Hopkins has become world renowned and synonymous with scholarly excellence and cutting 3400 N. Charles Street edge scientific research. Johns Hopkins has Baltimore, MD 21218 Graduate Program consistently ranked among the top universities by U.S. News and World Report. Director Professor Steven Rokita Department of Chemistry Living in Baltimore Johns Hopkins University 3400 N. Charles Street Baltimore is in the midst of an urban renaissance Baltimore, MD 21218 and offers ample recreational and cultural activities. Harborplace, located along the scenic Phone: 410-516-5793 Inner Harbor, is a striking collection of pavilions Fax: 410-516-8420 and promenades set at the water’s edge. The [email protected] National Aquarium adjoins Harborplace, as well as Camden Yards, home of the Baltimore Orioles, CBI Admissions Coordinator and M&T Bank Stadium, home of the 2012 NFL Lauren McGhee Super Bowl champions, the Baltimore Ravens. Phone: 410-516-7427 There are a number of major museums located Fax: 410-516-8420 within the city including the Walters Art Museum [email protected] and the Baltimore Museum of Art (adjacent to the Hopkins Campus). The Baltimore Symphony www.cbi.jhu.edu Orchestra offers a range of symphonic and “pop” music at the modern Joseph A. Meyerhoff concert Johns Hopkins University hall. In addition, a variety of festivals and special events occur in Baltimore including the Preakness and Artscape, the largest free public arts festival “I joined the CBI Program because, apart in the U.S. -

Historic Structure Report: Washington Light Infantry Monument, Cowpens National Battlefi Eld List of Figures

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cowpens National Battlefield Washington Light Infantry Monument Cowpens National Battlefield Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region Washington Light Infantry Monument Cowpens National Battlefi eld Historic Structure Report November 2018 Prepared by: WLA Studio RATIO Architects Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Cowpens National Battlefi eld 338 New Pleasant Road Gaffney, SC 29341 www.nps.gov/cowp About the cover: View of Washington Light Infantry Monument, 2017. Washington Light Infantry Monument Cowpens National Battlefield Historic Structure Report Superintendent, Recommended By : Recommended By : Date Approved By : Regional Director, Date Southeast Region Page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Historic Residential Suburbs

National Park Service National Register Bulletin U.S. Department of the Interior Clemson Universlti 3 1604 015 469 572 [ 29.9/2:H 62/7 HISTORIC RESIDENTIAL SUBURBS GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND DOCUMENTATION FOR THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES W»A/> ^ City of Portland T leu MAM- \ta '/• H a [rj«-« : National Register Bulletin HISTORIC RESIDENTIAL SUBURBS GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND DOCUMENTATION FOR THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES David L. Ames, University of Delaware Linda Flint McClelland, National Park Service September 2002 U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Above: Monte Vista School (T931), Albuquerque, New Mexico. In keeping with formal Beaux Arts pnnciples of planning, the Spanish Colonial Revival school was designed as an architectural landmark marking the entrance to the Monte Vista and College View neighborhoods. (Photo by Kathleen Breaker, courtesy New Mexico Office of Cultural Affairs) Inside front cover and title page: Plat (c. 1892) and Aerial View (1920), Ladd's Addition, Portland, Oregon. Platted as a streetcar suburb at the beginning of the City Beautiful movement, Ladd's Addition represents one of the earliest documented cases of a garden suburb with a complex, radial plan. (Plat and photograph courtesy Oregon Historical Society, negs. 80838 and 39917) ii National Register Bulletin Foreword America's Historic Suburbs for the made by many nomination preparers body of literature on The National Register of Historic Places," to the understanding of suburbaniza- America's suburbanization is which was circulated for review and tion in the United States. vast and growing, covering many dis- comment in fall of 1998. -

Maine Crusades and Crusaders, 1830-1850 and Addenda

Maine History Volume 17 Number 4 Article 3 4-1978 Maine Crusades and Crusaders, 1830-1850 and Addenda Richard P. Mallett University of Maine Farmington Roger Ray Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mallett, Richard P., and Roger Ray. "Maine Crusades and Crusaders, 1830-1850 and Addenda." Maine History 17, 4 (1978): 183-214. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol17/ iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD P. MALLETT Maine Crusades and Crusaders, 1830-1850 Soon after John Winthrop disembarked from the Arbella in 1630, he expressed the desire to see the Massachusetts Bay Colony build a city upon a hill that would promote the greater glory of God, and serve as a model for all mankind. Emphasizing as it would the sovereignty of God and a pious approach to community problems, this transplanted religious group was envisioned as develop ing an unprecedented sobriety of manners and purity o f morals. Some two hundred years later, it was obvious that Winthrop’s hopes had been somewhat excessive, but some descendants of the early Massachusetts settlers showed the same burning desire to know the will o f God as had the early colonists. The main difference was that in the nineteenth century the moral and religious zeal of the Puritans frequently took the form o f social reform and utopianism. -

Maryland's African-American Heritage Travel Guide 1 CONTENTS

MARYLAND'S MARYLAND VisitMaryland.org DEAR FRIENDS: In Baltimore, seeing is beiieuing. Saue 20% when you purchase the Legends S Legacies Experience Pass. Come face-to-face with President Barack Obama at the National Great Blacks In Wax Museum hank you for times to guide many and discover the stories of African American your interest in others to freedom. Today, visionaries at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum and Maryland's Maryland's Eastern the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park and Museum. African- Shore is keeping her tAmerican heritage and legacy alive through Book now and save. Call 1-877-BalHmore the spirit of perseverance sites and attractions, or visit BalHmore.org/herifage. that is at the heart of our and the Harriet Tubman shared history. Our State is Underground Railroad Byway. known for its rich history of local men and We celebrate other pioneers including women from humble backgrounds whose the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, our contributions helped strengthen the nation's first African-American Supreme foundation of fairness and equality to Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and which we continuously strive for today. Mathias de Sousa, the first black man to Just as our State became a pivotal set foot on what became the colony of place for Northern and Southern troop Maryland. We invite you to explore these movements during the Civil War, it also stories of challenge and triumph that became known for its network of paths, are kept alive through inspirational people and sanctuaries that composed the monuments, cultural museums and houses Effi^^ffilffl^fijSES Underground Railroad. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.