Grallina Cyanoleuca in This Paper I Describe an Unusual Foraging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Grassfinch Tour 2014 Trip Report

Experience the Wild TEN GRASSFINCH TOUR - Trip Report Day 1 Monday 22nd September, 2014 Date: Monday, 22 September 2014 Location: East Point Reserve continued... Australian White Ibis Threskiornis molucca Forest Kingfisher Todiramphus macleayii Orange-footed Scrubfowl Megapodius reinwardt Magpie-lark Grallina cyanoleuca Shining Flycatcher Myiagra alecto Australasian Figbird Sphecotheres vieilloti Yellow Oriole Oriolus flavocinctus Bar-shouldered Dove Geopelia humeralis Peaceful Dove Geopelia striata Pied Imperial-Pigeon Ducula bicolor Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Ptilinopus regina Rainbow Pitta Pitta iris Masked Lapwing Vanellus miles Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia Grey-tailed Tattler Tringa brevipes Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus Sunday night pre-tour dinner at Stokes Hill Wharf. Left to right - Mike Bush Stone-curlew Burhinus grallarius Jarvis (guide), Barry Venables, Phil Straw, Margaret Piefke, Brian Green-backed Gerygone Gerygone chloronota Large-billed Gerygone Gerygone magnirostris Speechley, Paddy Donkin, Donald Findlater. Phil was not a participant Grey Whistler Pachycephala simplex on the tour, Neil Brown arrived in the evening so was not at the dinner. Photo taken by Jenny Jarvis. Location: Sandy Creek Torresian Crow Corvus orru DAY 1 - DARWIN to PINE CREEK White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike Coracina papuensis White-winged Triller Lalage sueurii 7.00am Pick up from Darwin accommodation Brown Honeyeater Lichmera indistincta Rufous-throated Honeyeater Conopophila rufogularis White-gaped Honeyeater Lichenostomus unicolor We started off at East Point and walked the Monsoon White-throated Honeyeater Melithreptus albogularis Forest track looking for Rainbow Pitta and other Paperbark Flycatcher Myiagra nana monsoon forest specialists. After great views of no Red-collared Lorikeet Trichoglossus rubritorquis fewer than five Rose-crowned Fruit-doves, all had good Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos views of a Rainbow Pitta. -

Preliminary Systematic Notes on Some Old World Passerines

Kiv. ital. Orn., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STOBRS L. OLSON PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES TIPOGKAFIA FUSI - PAVIA 1989 Riv. ital. Ora., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STORRS L. OLSON (*) PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES Abstract. — The relationships of various genera of Old World passerines are assessed based on osteological characters of the nostril and on morphology of the syrinx. Chloropsis belongs in the Pycnonotidae. Nicator is not a bulbul and is returned to the Malaconotidae. Neolestes is probably not a bulbul. The Malagasy species placed in the genus Phyllastrephus are not bulbuls and are returned to the Timaliidae. It is confirmed that the relationships of Paramythia, Oreocharis, Malia, Tylas, Hyper - gerus, Apalopteron, and Lioptilornis (Kupeornis) are not with the Pycnonotidae. Trochocercus nitens and T. cycmomelas are monarchine flycatchers referable to the genus TerpsiphoTie. « Trochocercus s> nigromitratus, « T. s> albiventer, and « T. » albo- notatus are tentatively referred to Elminia. Neither Elminia nor Erythrocercus are monarch] nes and must be removed from the Myiagridae (Monarchidae auct.). Grai- lina and Aegithina- are monarch flycatchers referable to the Myiagridae. Eurocephalus belongs in the Laniinae, not the Prionopinae. Myioparus plumbeus is confirmed as belonging in the Muscicapidae. Pinarornis lacks the turdine condition of the syrinx. It appears to be most closely related to Neoeossypha, Stizorhina, and Modulatrix, and these four genera are placed along with Myadestes in a subfamily Myadestinae that is the primitive sister-group of the remainder of the Muscicapidae, all of which have a derived morphology of the syrinx. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

MORPHOLOGICAL and ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION in OLD and NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College O

MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Clay E. Corbin August 2002 This dissertation entitled MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS BY CLAY E. CORBIN has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences CORBIN, C. E. Ph.D. August 2002. Biological Sciences. Morphological and Ecological Evolution in Old and New World Flycatchers (215pp.) Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In both the Old and New Worlds, independent clades of sit-and-wait insectivorous birds have evolved. These independent radiations provide an excellent opportunity to test for convergent relationships between morphology and ecology at different ecological and phylogenetic levels. First, I test whether there is a significant adaptive relationship between ecology and morphology in North American and Southern African flycatcher communities. Second, using morphological traits and observations on foraging behavior, I test whether ecomorphological relationships are dependent upon locality. Third, using multivariate discrimination and cluster analysis on a morphological data set of five flycatcher clades, I address whether there is broad scale ecomorphological convergence among flycatcher clades and if morphology predicts a course measure of habitat preference. Finally, I test whether there is a common morphological axis of diversification and whether relative age of origin corresponds to the morphological variation exhibited by elaenia and tody-tyrant lineages. -

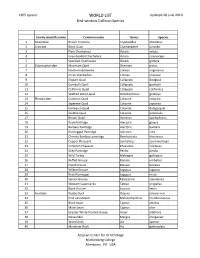

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

FIELD GUIDES BIRDING TOURS: Australia

Field Guides Tour Report Australia - Part Two 2012 Oct 9, 2012 to Oct 24, 2012 John Coons & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. A Crested Pigeon shows his fantastic fan. The one on the left didn't seem impressed...but we were! (Photo by guide Jesse Fagan) We had nearly 300 species of birds on the mainland trip, plus some really cool mammals, and those who went on the Tasmania extension saw even more goodies (another 41 new species!) plus devils. It was indeed a good tour from the Top End of Down Under -- from Darwin to Cairns, "out" in the Outback, and along the coast to Brisbane. Those on the extension headed further south still and ended in up Hobart. The weather cooperated this year. Sun in Darwin and most other places, and very little rain before our arrival meant watering holes around Georgetown were productive...very productive. More than 200 Diamond Doves coming in to drink were very impressive along with numerous Zebra Finches and those Dingos. The cassowary experience left us speechless -- a truly ancient and impressive species, and the bird of the trip for most folks. The shorebird spectacle along the Cairns Esplanade is always a treat, though we fought the tides a bit this year. No real shorebird rarities, but a gathering of thousands of Sharp-tailed Sandpipers and Great Knots is not something you see everyday. There were some impressive bowers too: Great Bowerbirds with their grays and greens, Satin Bowerbirds with their intense blues; some bowers were just simple leaves in a clearing like that of the Tooth-billed Catbird, and then there was the Golden Bowerbird bower. -

Brood Parasitism by Banded Bay Cuckoo Cacomantis

22 Indian Birds VOL. 17 NO. 1 (PUBL. 29 MARCH 2021) The Painted Stork is globally Near Threatened (BirdLife International 2016b) and a nationally endangered stork with an estimated population of 50 (Inskipp et al. 2016). The largest flock of the Painted Storks, before the above, was recorded in December 1979, when 57 birds were counted at Gaidahawa Lake, Rupandehi District (Underwood 1980) 185 km east of the present record. Southwards of Badhaiya Lake, in Uttar Pradesh, India, there are 12 colonies of Painted Stork (Tiwary et al. 2014) that could be the source population for this congregation in Nepal. The present record spreads optimism as Nepal was earlier known to harbour very few populations of the Painted Stork. We would like to thank Carol Inskipp and Hem Sagar Baral for 34. A part of the flock of Sarus Crane observed at Jagadishpur Reservior. their constructive comments in this manuscript. Our study was funded by The Rufford foundation, UK, to PG. References BirdLife International. 2008. Congregation at particular sites is a common behaviour in many bird species. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 11/08/2020 [Accessed on 10 August 2020] BirdLife International. 2016a. Antigone antigone. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22692064A93335364. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016- 3.RLTS.T22692064A93335364.en. [Accessed on 11 August 2020.] Both: Prashant Ghimire BirdLife International. 2016b. Mycteria leucocephala. The IUCN Red List of Threatened 35. A part of the flock of Sarus Crane observed in farmland nearby Jagadishpur Reservoir. Species 2016: e.T22697658A93628598. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016- 3.RLTS.T22697658A93628598.en. -

Breeding System Evolution Influenced the Geographic

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12695 Breeding system evolution influenced the geographic expansion and diversification of the core Corvoidea (Aves: Passeriformes) Petter Z. Marki,1,2,3,∗ Pierre-Henri Fabre,1,4 Knud A. Jønsson,1,5,6 Carsten Rahbek,1,5 Jon Fjeldsa,˚ 1 and Jonathan D. Kennedy1,∗ 1Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 2Department of Environmental and Health Studies, Telemark University College, Hallvard Eikas Plass, N-3800 Bø, Norway 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 5Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus, Ascot, West Berkshire, SL5 7PY, United Kingdom 6Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom Received July 9, 2014 Accepted May 20, 2015 Birds vary greatly in their life-history strategies, including their breeding systems, which range from brood parasitism to a system with multiple nonbreeding helpers at the nest. By far the most common arrangement, however, is where both parents participate in raising the young. The traits associated with parental care have been suggested to affect dispersal propensity and lineage diversification, but to date tests of this potential relationship at broad temporal and spatial scales have been limited. Here, using data from a globally distributed group of corvoid birds in concordance with state-dependent speciation and extinction models, we suggest that pair breeding is associated with elevated speciation rates. Estimates of transition between breeding systems imply that cooperative lineages frequently evolve biparental care, whereas pair breeders rarely become cooperative. -

Bird Watching Top End 2012 Trip Report

Territory Discoveries Bird Watching in the Top End Tour 10-17 September 2012 Trip Report Bird Watching in the Top End Tour – September 2012 TERRITORY DISCOVERIES CONTACT DETAILS Contact: Amanda Hales or Jason Harvey Ph: 1800 642 343 Fax: 1800 808 666 Email: [email protected] www.territorydiscoveries.com/groups EXPERIENCE THE WILD Mike Jarvis (Guide) 0429 021 160 [email protected] www.experiencethewild.com.au Guests Lewis and Jeanette from Sydney Bob from Victoria Bruce from Canberra and Pauline from Golburn SIGHTINGS DAY 1 10th September, 2012: Afternoon Bird Highlights & Location: Knuckey Lagoons Welcome Dinner Magpie Goose Anseranas semipalmata Plumed Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna eytoni Wandering Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna arcuata We met up as a group at 2.30pm on Monday 10th September and Radjah Shelduck Tadorna radjah after brief introductions all round, headed down out to Knuckey Green Pygmy-goose Nettapus pulchellus Lagoon’s. Here we saw a good number of wetland birds, some Pacific Black Duck Anas superciliosa Hardhead Aythya australis such as Radjah Shelduck and Pied Heron were lifers for those who Australasian Grebe Tachybaptus novaehollandiae had not visited Darwin before. Australasian Darter Anhinga novaehollandiae Little Pied Cormorant Microcarbo melanoleucos Then we visited the mangrove boardwalk at East Point, picking up Little Black Cormorant Phalacrocorax sulcirostris Australian Pelican Pelecanus conspicillatus several of the mangrove specialists, then searched the monsoon Eastern Great Egret Ardea modesta forest for the Rainbow Pitta. Unfortunately no Pitta was seen or Intermediate Egret Ardea intermedia heard, but we did see Red-tailed Black Cockatoos and Agile Cattle Egret Ardea ibis Wallabies. Pied Heron Egretta picata Little Egret Egretta garzetta Straw-necked Ibis Threskiornis spinicollis We returned to the Novotel, enjoyed some drinks from the Jabiru Whistling Kite Haliastur sphenurus Bar and did our first bird call for the trip. -

Papua New Guinea II

Papua New Guinea II 22nd July - 8th August 2007 Trip Report compiled by Stephen F. Bailey & Erik Forsyth RBT Papua New Guinea II July 2006 2 Top twelve birds of the trip as voted by the participants 1. Greater Bird-of-paradise 2. Southern Crowned-Pigeon 3. King-of-Saxony Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). King Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). Wallace’s Fairywren 6(tie). Crested Bird-of-paradise 6(tie). Greater Melampitta 8. Palm Cockatoo 9. Crested Berrypecker 10(tie). Brehm’s Tiger-Parrot 10(tie). Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia 10(tie). Blue Bird-of-paradise Tour Summary Our tour of Papua New Guinea began as we boarded our aircraft to the South Pacific islands of the Bismarck Archipelago for the pre-tour extension. First-off, we visited the rainforest of the Pokili Wildlife Management Area which holds the largest breeding colony of Melanesian Scrubfowl in the world. It was an amazing experience to wander through the massive colony of these bizarre birds. We also managed outstanding views of the gorgeous Black-headed Paradise-Kingfisher, Blue-eyed Cockatoo and Red- knobbed Imperial-Pigeon. Some participants were fortunate to spot the rare Black Honey Buzzard. Then we took time to explore several small, remote tropical islands in the Bismarck Sea and were rewarded with sightings of Black-naped Tern, the boldly attractive Beach Kingfisher, Mackinlay’s Cuckoo-Dove and the extraordinary shaggy Nicobar Pigeon. Back on the main island, we visited the Pacific Adventist University, where we found a roosting Papuan Frogmouth, White-headed Shelduck and Comb-crested Jacana. -

Flycatchers (Terpsiphone

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2012) 39, 1900–1918 ORIGINAL Dynamic colonization exchanges ARTICLE between continents and islands drive diversification in paradise-flycatchers (Terpsiphone, Monarchidae) Pierre-Henri Fabre1*, Martin Irestedt2, Jon Fjeldsa˚1, Rachel Bristol3, Jim J. Groombridge3, Mohammad Irham4 and Knud A. Jønsson1 1Center for Macroecology Evolution and ABSTRACT Climate at the Natural History Museum of Aim We use parametric biogeographical reconstruction based on an extensive Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen DNA sequence dataset to characterize the spatio-temporal pattern of colonization Ø, Denmark, 2Molecular Systematics of the Old World monarch flycatchers (Monarchidae). We then use this Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural framework to examine the role of dispersal and colonization in their evolutionary History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, diversification and to compare plumages between island and continental Sweden, 3Durrell Institute of Conservation and Terpsiphone species. Ecology, School of Anthropology and Location Africa, Asia and the Indian Ocean. Conservation, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NR, UK, 4Research Center For Biology, Methods We generate a DNA sequence dataset of 2300 bp comprising one Cibinong Science Center (CSC), JL. Raya nuclear and three mitochondrial markers for 89% (17/19) of the Old World Jakarta – Bogor Km.46, Cibinong 16911, Monarchidae species and 70% of the Terpsiphone subspecies. By applying Bogor, Indonesia maximum likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic methods and implementing a Bayesian molecular clock to provide a temporal framework, we reveal the evolutionary history of the group. Furthermore, we employ both Lagrange and Bayes-Lagrange analyses to assess ancestral areas at each node of the phylogeny.