The Exploration of Selected Cross-Genre Compositions for Clarinet and Saxophone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

00 Primeras Paginas Rha5

RHA, Vol. 5, Núm. 5 (2007), 137-148 ISSN 1697-3305 NON-ASHKENAZIC JEWRY AS THE GROUND OF CONTEMPORARY ISRAELI MULTICULTURALISM Zvi Zohar* Recibido: 4 Septiembre 2007 / Revisado: 2 Octubre 2007 / Aceptado: 20 Octubre 2007 1. HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL Sephardic rabbinic authorities branded this deve - BACKGROUND lopment as illegitimate. Later, they realized that In the wake of the Expulsion from Spain not only was such opposition futile, but that many (1492), Sephardic1 Jews gradually settled as Sepharadim were in fact purchasing meat from refugees in many lands, primarily – in areas under Ashkenazic shehita. Thereafter, the Sephardic rab- Ottoman rule. One of these was the Holy Land, bis concentrated on de-legitimizing consumption Eretz Israel, whose Jewish inhabitants until that of such meat by Sepharadim; by and large, this time were mostly indigenous Musta’arabim2. For a campaign also failed, since the “Ashkenazic” pro- variety of reasons, the Musta’arabim gradually duce was less expensive. Ashkenazic influence upon became assimilated to the culture of the Sephardic Sepharadim manifested itself also in other aspects newcomers. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, the of traditional Jewish life – such as recitation of ri - dominant (‘hegemonic’) culture of Jews in Eretz tual benedictions by women, and the adoption by Israel (henceforth: EI) was Sephardic. However, certain Sephardic rabbis of ultra-Orthodox rejec- beginning in the late 18th century, and especially tionism towards, e.g., secular studies. during and after the brief Egyptian rule (1831 In the instances discussed above, various ethni - –1840), increased Jewish immigration from cally Jewish sub-groups interacted and influenced Eastern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East each-other with regard to varieties of Jewish cultu - led to the establishment of non-Sephardic commu- ral norms. -

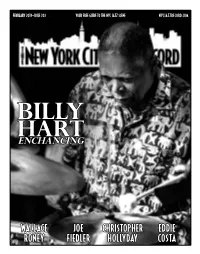

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Gala Concert Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

BOURGIE HALL GALA CONCERT MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS FEATURING WORLD PREMIERES BY OCTOBER KEIKO DEVAUX, YOTAM HABER 8 P.M. (ET) & YITZHAK YEDID SPECIAL LIVESTREAM LE NOUVEL ENSEMBLE MODERNE LORRAINE VAILLANCOURT, MEDICI.TV CONDUCTOR FACEBOOK.COM/AZRIELIMUSIC ABOUT THE AZRIELI FOUNDATION Inspired by the values and vision of our founder, David J. Azrieli z”l, the mission of the Azrieli Foundation is to improve the lives of present and future generations through Education, Research, Healthcare and the Arts. We are passionate about the promise and importance of a rigorous yet creative approach to philanthropy. We believe that strategic leadership, collaboration and forward thinking are key to bold discoveries. In addition to making philanthropic investments across our priority areas, the Foundation operates a number of programs, including the Azrieli Music Prizes, the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program, the Azrieli Fellows Program, the Azrieli Science Grants Program and the Azrieli Prize in Architecture. Our vision is to remember the past, heal the present and enhance the future of the Jewish people and all humanity. To learn more: www.azrielifoundation.org A Message from SHARON AZRIELI We are thrilled to celebrate with you the third Israeli-born Yitzhak Yedid’s Kadosh Kadosh and shaping cultural identity and educating present Azrieli Music Prizes Gala Concert. Cursed unites contemporary Western music and future generations. The questions, “What is and ancient Mizrahi songs across twenty-four Jewish music?” and “What is Canadian music?” What a remarkable adventure the Prizes musical scenes. Together, they showcase a ask composers to amplify and honour stories have had since we fêted our 2018 Laureates. -

Integrating Elements of Persian Classical Music with Jazz

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2013 A transcultural journey : integrating elements of Persian classical music with jazz Kate Pass Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pass, K. (2013). A transcultural journey : integrating elements of Persian classical music with jazz. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/116 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/116 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Use of Thesis This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However the literary rights of the author must also be respected. If any passage from this thesis is quoted or closely paraphrased in a paper or written work prepared by the user, the source of the passage must be acknowledged in the work. If the user desires to publish a paper or written work containing passages copied or closely paraphrased from this thesis, which passages would in total constitute and infringing copy for the purpose of the Copyright Act, he or she must first obtain the written permission of the author to do so. -

The Avant-Garde 15

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 407 ORNETTE COLEMAN lonely woman CECIL TAYLOR bulbs CECIL TAYLOR willisau concert, part 3 ALBERT AYLER ghosts DAVID MURRAY el matador THE AVANT-GARDE 15 Forward March T e word “avant-garde” originated in the French military to denote the advanced guard: troops sent ahead of the regular army to scout unknown territory. In English, the word was adapted to describe innovative composers, writers, painters, and other artists whose work was so pioneering that it was believed to be in the vanguard of contemporary thinking. Avant-gardism represented a movement to liberate artists from the restraints of tradition, and it often went hand-in-hand with progressive social thinking. T ose who championed avant-garde art tended to applaud social change. T ose who criticized it for rejecting prevailing standards couched their dismay in warnings against moral laxity or political anarchy. In the end, however, all art, traditional or avant-garde, must stand on its merit, inde- pendent of historic infl uences. T e art that outrages one generation often becomes the tradition and homework assignments of the next: the paintings of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso, music of Gustav Mahler and Claude Debussy, and writings of Marcel Proust and James Joyce were all initially considered avant-garde. Two especially promi- nent twentieth-century avant-garde movements gathered steam in the decades follow- ing the world wars, and jazz was vital to both. Sonny Rollins combined the harmonic progressions of bop with the freedom of the avant-garde and sustained an international following. He appeared with percussionist Victor See Yuen and trombonist Clifton © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM Anderson at a stadium in Louisiana, 1995. -

Respectability and the Modern Jazz Quartet; Some Cultural Aspects of Its Image and Legacy As Seen Through the Press

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Respectability and The Modern Jazz Quartet; Some Cultural Aspects of Its Image and Legacy As Seen Through the Press Carla Marie Rupp CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/74 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Respectability and The Modern Jazz Quartet: Some Cultural Aspects of Its Image and Legacy As Seen Through the Press By Carla Marie Rupp Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the M.A. Degree The City College of New York Thesis Adviser, Prof. Barbara R. Hanning The Department of Music Fall Term 2010 2 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. RESPECTABILITY THROUGH DRESS 22 3. PERFECTION IN PRESENTATION 29 4. CHANGING THE VENUE FROM NIGHT CLUB TO CONCERT HALL 34 5. PROFESSIONALISM OF THE MJQ 43 6. PERSONAL CONCLUDING REMARKS 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY 54 3 Acknowledgements I would like to give a big thanks of gratitude and applause to the incredible Professor Barbara R. Hanning for being my thesis advisor! Her dedication, personal editing, attention to detail and accuracy, kindness and help were invaluable in completing this project on the MJQ. As Chair of the Music Department, she advised me on my BFA requirements in music at City College. And now--some years later with Professor Hanning's encouragement, wisdom and editing--I am thrilled to complete my M.A. -

Segni Si Candida Dell Accademia Dei Lini Ei a PAQINA «J 8 Un Anno Fa La Tragedia MASSIMO L

Giornale -i- Inserto Anno 69" n 85 Spedizione in abbonamento postale gr 1/70 L 1200/arretratiL 2-100 Venerdì SCCEW COOPERATO* 10 aprile 1992* r Unitdomale fondato da Antoniào Gramsci È morto Daniel Bovet Nobel Editoriale Il leader dei referendum lancia la sua candidatura a Palazzo Chigi: per ora reazioni fredde per la mediana Nella De venti di rivolta contro Forlani. E De Mita propone un esecutivo costituente È morto Daniel Bovet uno dei fondatori della moderna chi mica farmacologica A\,eva scoperto tra 1 altro i sulfamidici cioè i farmaci anU-batti'n Svizzero di nascita ma italiano di adozione aveva nccvuo il Premio Nobel per la medicina * La rivoluzione nel 1957 Nel dopoguerra si trasferì in Italia dopo aver lavo rato ali istituto Pasteur i\ Pangi Gran parte dei farmaci sco perti in epoca successiva derivano dall applicazione delle copernicana che serve sue ricerche sulle molecole di sintesi Dal 1958 era membro * alla sinistra Segni si candida dell Accademia dei Lini ei A PAQINA «J 8 Un anno fa la tragedia MASSIMO L. SALVADOR! «Faccio io il éovemo delle riforme» della Moby motivo di grande soddisfazione per chi consi Mano Segni si candida alla guida di un governo di Prince dera I unita un obiettivo storico che la sinistra transizione per le riforme 11 deputato sardo attacca deve tenacemente perseguire leggere la con clusione del documento dell Esecutivo sociali- Il Pds duramente la De e indica nelle nuove regole eletto Qualcosa si muove ____E_ sta dovesi indiai la necessità di «un nuovodia rali e ne!l' «abbattimento della partitocrazia» -

Jewish Music

Jewish Music A Concise Study by Mehmet Okonşar [the appendices, containing copyrighted material are removed in this copy] Released by the author under the terms of the GNU General Public Licence Contents Introduction: What Is Jewish Music? 1 How Many Jewish Musics? 4 The Three Main Streams . 4 Ashkenazi and the Klezmer . 4 Sephardi.............................. 5 Mizrahi . 6 Sephardi or Mizrahi? . 6 Genres of Liturgical Music 8 Music in Jewish Liturgy . 8 Genres, Instruments and Performers . 9 Generalities . 9 Bible Cantillation . 9 The Cantor . 12 Prayer-Chant . 12 Piyyutim .............................. 13 Zemirot .............................. 13 Nigunim .............................. 13 Biblical Instrumentarium . 15 Usage of Musical Terms in Hebrew . 19 The Biblical soggetto cavato ...................... 20 Summary of the Archaeological Aspects of Jewish Music . 21 Some Jewish Composers 22 Salomone Rossi (1570-1630) . 22 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) . 25 Fromental Hal´evy (1799-1862) . 29 Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) . 32 Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) . 35 Georges Gershwin (1898-1937) . 38 ii Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) . 39 Conclusion on Jewish Composers . 43 Jewish Music by non-Jewish Composers 45 Max Bruch and Kol Nidrei ....................... 45 Kol Nidrei . 45 Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) and Kaddish-Deux M´elodies H´ebra¨ıques 50 Sergei Prokofieff and Overture sur des Th`emesJuifs . 54 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) and Babi Yar . 55 In The Twenty-first Century 60 Diversification . 60 Appendices 62 Radical Jewish Culture by John Zorn . 62 Russian Society for Jewish Music . 64 Jewish Music Research Centre . 66 Wagner and the “Jewness” in Music . 67 The original article of 1850 . 67 Reception of the 1850 article . 69 1850-1869 . 69 The 1869 version and after . -

Programma Torino Jazz Festival 2013

Un progetto di realizzato da main partner con il sostegno di media partner Dal 26 aprile al 1° maggio torna il Torino Jazz Festival e, lascian- doci travolgere ancora dal ritmo e dalle emozionanti blue note, ritroveremo una città nella città. Piazza Castello, Piazzale Valdo Fusi, Piazza Vittorio Veneto e le suggestive rive del Po sapranno restituirci la stessa coinvolgente atmosfera che l’anno passato ci ha permesso di riscoprire il profondo legame del nostro ter- ritorio con questa intramontabile tradizione musicale. Dopo il successo di pubblico della prima edizione, abbiamo da subito pensato e lavorato con entusiasmo ad una rassegna ancora più ricca di concerti, eventi, mostre, incontri, attraverso un viaggio concepito per entrare in contatto e vivere a pieno il meglio della cultura afroamericana. Una novità importante che da quest’anno caratterizza il Festival è l’attenzione dedicata agli aspetti educativi del jazz, con mo- menti di alta formazione musicale, incontri con le scuole, at- tenzione al mondo giovanile e agli artisti di nuova generazione. Ogni giorno inoltre la rassegna propone alcuni percorsi tema- tici, veri e propri festival nel festival, all’interno dei quali spicca la programmazione del 30 aprile che, in occasione della gior- nata internazionale Unesco per il jazz, offre un lungo filo rosso di appuntamenti dal forte significato sociale, oltre che di alto profilo artistico. Il nostro ringraziamento va a tutti coloro che, attraverso un sostegno economico o mettendo a disposizione le proprie ca- pacità, rendono possibile questo ambizioso progetto, che offre ai torinesi e ai tanti turisti l’occasione di vivere i momenti di grande crescita culturale e di autentica passione musicale che questi sei giorni promettono. -

Hidden in Plain View---The Legacy of Eric Dolphy

JEROME HARRIS New World Records 80472 Hidden in Plain View HIDDEN IN PLAIN VIEW---THE LEGACY OF ERIC DOLPHY "I want to say more on my horn than I ever could in ordinary speech." Eric Dolphy1 Look up Eric Dolphy in any contemporary encyclopedic jazz history and you are likely to find an entry something like this: Eric Allen Dolphy was born in Los Angeles on June 20, 1928 and died in Berlin thirty-six years and nine days later on June 29, 1964. A formidable soloist on alto saxophone, flute, and bass clarinet, he began playing clarinet at age six and was playing professionally in dance bands by junior high school. He studied music at Los Angeles City College and, while in the service, at the U.S. Naval School of Music. Upon leaving the military, he returned to L.A. and became a fixture in the West Coast jazz scene, ultimately joining Chico Hamilton's quintet in 1958. 1959 found him in New York, a member of the Charles Mingus band, a freelance player, and the leader of recording dates under his own name. Despite his burgeoning fame, he found little employment in the United States--although he did co- lead a quintet with Booker Little--and left for Europe in the fall of 1961, where he played as a bandleader and as a member of John Coltrane's band. He also played in John Lewis' Orchestra U.S.A. and in Gunther Schuller's Third Stream melding of art-music and jazz sensibilities. Dolphy spent most of the last year of his life working as a freelance musician, primarily for Mingus, Lewis, and Coltrane. -

Nota De Prensa El Jazz Y El Clásico Hacen 'Match

Publicado en Alicante el 05/08/2020 El Jazz y el Clásico hacen ‘match’ en Symphonic Jazz Sketches El pasado 31 de julio, el auditorio de la diputación de Alicante (ADDA) cerró su temporada sinfónica con un concierto de excepción, Symphonic Jazz Sketches, el evento musical que fusiona el mundo clásico de las orquestas sinfónicas con el mundo del Jazz y donde la trompeta es la principal protagonista Un proyecto musical, en el que el versátil director musical Miguel Ángel Navarro, capitanea la unión entre dos estilos aparentemente diferentes, el clásico y el jazz. David Pastor, trompetista famoso por su virtuosismo y sensibilidad, interpretó el repertorio como solista, acompañado por la orquesta ADDA Simfònica y su cuarteto de Jazz clásico (contrabajo, piano y batería). La delgada línea que divide el Clásico y el Jazz La conexión entre el jazz y la música clásica es a menudo difícil de apreciar por los oyentes. ¿Dónde está el elemento diferencial? Mientras que la música de jazz, estrictamente definida, contiene al menos un elemento único, el swing beat; el arte de la improvisación tiene una larga historia que remonta a la música más antigua. Los grandes compositores barrocos, clásicos y románticos como Bach, Mozart o Liszt ya eran grandes improvisadores. En realidad los límites entre el jazz y la música clásica no existen como tal. Third Stream de Schüller la teoría que unió el jazz y la música clásica. En 1960, para el álbum Jazz Abstractions, Gunther Schuller reunió a los músicos de jazz más increíbles -Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Bill Evans y Jim Hall- y a un cuarteto de cuerdas contemporáneo con un proyecto que empujó a los instrumentistas a nuevas direcciones para crear algo que deslumbró la imaginación.