Combating Infectious Diseases Hearing Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HON. JESSE HELMS ÷ Z 1921–2008

im Line) HON. JESSE HELMS ÷z 1921–2008 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Jesse Helms LATE A SENATOR FROM NORTH CAROLINA MEMORIAL ADDRESSES AND OTHER TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE congress.#15 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office Jesse Helms VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE 43500.002 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) S. DOC. 110–16 Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes HELD IN THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES TOGETHER WITH A MEMORIAL SERVICE IN HONOR OF JESSE HELMS Late a Senator from North Carolina One Hundred Tenth Congress Second Session ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) CONTENTS Page Biography ................................................................................................. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Harvard Public Health Review Fall 2008

Harvard Public Health Review Fall 2008 WILL DIGITAL HEALTH RECORDS FIX U.S. HEALTH CARE? INSIDE New HSPH Dean Julio Frenk XDR-TB marches on Health and taxes Surgical checklist Genes and environment Disasters in China and Myanmar Amazing alumni HARVA RD School of Pu blic Health DEAN OF THE FACULTY VISITING COMMITTEE DEAN’S COUNCIL Barry R. Bloom Steven A. Schroeder Gilbert Butler Chair Walter Channing, Jr. Harvard ALUMNI COUNCIL Barrie M. Damson Ruth L. Berkelman Mitchell L. Dong Jo Ivey Boufford The Harvard Public Health Review Officers John H. Foster Louis W. Cabot is published three times a year for Mark S. Clanton, mph ’90 A. Alan Friedberg Nils Daulaire supporters and alumni of the Harvard President C. Boyden Gray Nicholas N. Eberstadt School of Public Health. Its readers share Rajat Gupta Royce Moser, Jr., mph ’65 Cuthberto Garza a commitment to the School’s mission: Julie E. Henry, mph ’91 President-Elect Jo Handelsman advancing the public’s health through Stephen B. Kay Elsbeth Kalenderian, mph ’89 Gary King learning, discovery, and communication. Rachel King Secretary Jeffrey P. Koplan Nancy T. Lukitsh Risa Lavizzo-Mourey Harvard Public Health Review J. Jacques Carter, mph ’83* Beth V. Martignetti Bancroft Littlefield Harvard School of Public Health Immediate Past President David H. M. Matheson Nancy L. Lukitsh Office for Resource Development Richard L. Menschel Vickie M. Mays Third Floor, East Atrium Councilors Ahmed Mohiuddin Michael H. Merson 401 Park Drive 2005-2008 Adeoye Y. Olukotun, Anne Mills Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Bethania Blanco, SM ’73 mph ’83 Kenneth Olden (617) 384-8988 Marise S. -

Vaccine Visions and Their Global Impact

© 1998 Nature Publishing Group http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine COMMENTAR' Barry Bloom (a Howard Hughes Investigator at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and Roy Widdus (Coordinator of the Children's Vaccine Initiative) describe their vision of global implementation of vaccines, highlighting what has already been achieved and, perhaps more importantly, what remains to be done. They also call for further efforts to develop the broad collaborations required to achieve a new vision for global vaccine use. Vaccine visions and their global impact Shortly after the assassination of Prime tain because, as Lewis Thomas noted, we Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984, Jim BARRY R. BLOOM1 tend to take for granted the technologies 2 Grant, Administrator of UNICEF and & ROY WIDDUS that work best2• Hafdan Mahler, Director-General of The third great vision-the eradication World Health Organization (WHO), flew to New Delhi on an of paralytic poliomyelitis-is on the way to being achieved. extraordinary mission. They proposed to her surviving son, Although the scientific problems of creating safe and effective Rajiv, that instead of building a shrine or temple, he honor his polio vaccines were largely overcome by the 1960s, to have mother by making a commitment to immunize all the children global impact, political problems must also be overcome. Few of India against poliomyelitis by the end of the century. On countries want their infectious diseases to be publicly reported, December 6 and 7, 1996, in two National Vaccine Days, 121 and Ciro de Quadros of the Pan American Health Organization million Indian children were vaccinated against polio at came up with a brilliantly imaginative solution to a delicate 650,000 immunization posts by 2.6 million volunteers. -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

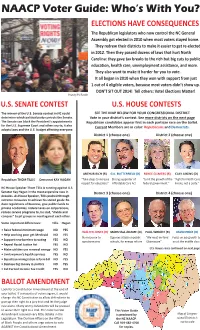

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’S with You?

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’s With You? ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES The Republican legislators who now control the NC General Assembly got elected in 2010 when most voters stayed home. They redrew their districts to make it easier to get re-elected in 2012. Then they passed dozens of laws that hurt North Carolina: they gave tax breaks to the rich but big cuts to public education, health care, unemployment assistance, and more. They also want to make it harder for you to vote. It all began in 2010 when they won with support from just 1 out of 4 eligible voters, because most voters didn’t show up. DON’T SIT OUT 2014! Tell others: Vote! Elections Matter! Photo by Phil Fonville U.S. SENATE CONTEST U.S. HOUSE CONTESTS The winner of the U.S. Senate contest in NC could SEE THE MAP BELOW FOR YOUR CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT determine which political party controls the Senate. Vote in your district’s contest. See more districts on the next page The Senate can block the President’s appointments Republican candidates appear first in each partisan race on the ballot. for the U.S. Supreme Court and other courts; it also Current Members are in color: Republicans and Democrats. adopts laws and the U.S. budget affecting everyone. District 1 (choose one) District 2 (choose one) ARTHUR RICH (R) G.K. BUTTERFIELD (D) RENEE ELLMERS (R) CLAY AIKENS (D) Republican THOM TILLIS Democrat KAY HAGAN “Take steps to increase Strong supporter of “Limit the growth of the “Fight for North Caro- respect for educators” Affordable Care Act federal government.” linians, not a party.” NC House Speaker Thom Tillis is running against U.S. -

105Th Congress 215

NORTH CAROLINA 105th Congress 215 NORTH CAROLINA (Population 1995, 7,195,000) SENATORS JESSE HELMS, Republican, of Raleigh, NC; born in Monroe, NC, October 18, 1921; at- tended Wingate College and Wake Forest College; U.S. Navy, 1942±45; former city editor, Ra- leigh Times; administrative assistant to U.S. Senator Willis Smith, 1951±53, and to U.S. Senator Alton Lennon, 1953; executive director, North Carolina Bankers Association, 1953±60; execu- tive vice president, WRAL±TV and Tobacco Radio Network, 1960±72; member, Raleigh City Council, chairman of Law and Finance Committee, 1957±61; deacon and Sunday School teach- er, Hayes Barton Baptist Church, Raleigh; recipient of two Freedom Foundation awards for radio-television editorials; recipient of annual citizenship awards from North Carolina American Legion, North Carolina Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Raleigh Exchange Club; recipient of Outstanding Service Award of the Council Against Communist Aggression, the Richard Henry Lee Award, and the Order of Lafayette Freedom Award; former trustee, Meredith College, John F. Kennedy College, Delaware Law School, Campbell University, and Wingate College; presi- dent, Raleigh Rotary Club, 1969±70; 33rd degree Mason: Grand Orator, Grand Lodge of Ma- sons of North Carolina, 1964±65, 1982, 1991; member, board of directors, North Carolina Cere- bral Palsy Hospital; member, board of directors of Camp Willow Run, a youth camp for Christ at Littleton, NC; married Dorothy Jane Coble of Raleigh, October 31, 1942; three children: Jane (Mrs. Charles R. Knox), Nancy (Mrs. John C. Stuart), and Charles; seven grandchildren; com- mittees: Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; chairman, Foreign Relations; Rules and Adminis- tration; elected to the U.S. -

Investing in Our Common Future

Investing in Our Common Future 2 Page 2 Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Background Paper for the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health: Investing in Our Common Future Working Papers of the Innovation Working Group - Version 2 Contents Page Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 5 Tore Godal, Special Adviser to the Prime Minister of Norway on Global Health - Co-Chair, Innovation Working Group, Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Scott C Ratzan, Vice-President, Global Health, Government Affairs & Policy, Johnson & Johnson - Co-Chair, Innovation Working Group, Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 7 1. Results-Based Financing (RBF) In Service Demand and Delivery ……………………………...……… 11 Health Results Innovation Program Team: Darren Dorkin, Petra Vergeer, Rachel Skolnik and Jen Sturdy of the World Bank 2. The Health Systems Funding Platform ………………………………………………………………….…..…. 15 GAVI Alliance, The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, World Bank and World Health Organization 3. Public-Private Partnership Models …………………………………………………………………….……..... 19 Barry Bloom, Professor of Public Health, Harvard School of Public Health Wendy Woods, Partner and Managing Director, Boston Consulting Group 4. Innovative Use of Mobile Phones and Related Information and Communication Technologies ….... 28 Scott C Ratzan, MD, Vice-President, Global Health, Government Affairs & Policy, Johnson & Johnson Denis Gilhooly, Executive Director, Digital He@lth Initiative, United Nations 5. New and Emerging Medical Technologies ……………………………………………………………..………. 36 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Program Officers Andrew Serazin and Margaret Cornelius 6. Innovative Technologies for Women’s and Children’s Health ………………………………..………….. 39 Christopher J Elias, MD, MPH, President and CEO, PATH 7. Innovations on The Indian Scene that Relate to Improved Maternal and Newborn Health …..…. -

The Senate "Two-Hour Rule"

The Senate “Two-Hour Rule” Governing Committee Meeting Times Christopher M. Davis Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process Michael Greene Senior Research Librarian April 20, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45170 The Senate “Two-Hour Rule” Governing Committee Meeting Times Summary Paragraph 5(a) of Senate Rule XXVI, sometimes referred to as the “two-hour rule,” restricts the times that most Senate committees and subcommittees can meet when the full Senate is in session. The rule is intended to help balance the Senate’s committee and floor work and to minimize the logistical conflicts that Senators face between participating in committee hearings and markups and attending to their duties on the chamber floor. Under the terms of the rule, no Senate committee or subcommittee (except the Committees on Appropriations and Budget and their subcommittees) can meet after the Senate has been in session for two hours or past 2:00 p.m. unless one of the following things occur: (1) the Senate grants unanimous consent for them to meet; (2) both the majority and minority leaders (or their designees) agree to permit the meeting, and their agreement has been announced on the Senate floor; or (3) the Senate adopts a privileged motion to allow the meeting. Should a committee meet during a restricted time period without being granted permission, any action that it takes—such as ordering a bill or nomination reported to the Senate—is considered “null, void, and of no effect.” Senate rules restricting committee meeting times have existed for over 70 years and have evolved over time. -

The Senate 16 Chapter Three: a President Pro Tem Fo

Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Marc the Man 3 Chapter Two: The Senate 16 Chapter Three: A President Pro Tem for the Northeast 31 Chapter Four: The Great Senate Organization 51 Epilogue: After Marc 61 Acknowledgements 63 Notes 64 Bibliography 71 Introduction “Now neither party had ever, ever helped Dare County or northeastern North Carolina, as I saw it. Ehringhaus in Elizabeth City a little, but no connecting roads anywhere, north or south or west, no educational opportunities much, not much, no economy except for that that was self generated.” –Marc Basnight1 On August 24th, 2013, I drove eastward from the University of North Carolina in order to watch my alma mater, Currituck County High School, open the football season against Manteo. Leaving Chapel Hill in the mid afternoon, I arrived on the campus of the small Roanoke Island school in a touch under three and a half hours. In the 1970s, this trip would have lasted no less than five and possibly up to six hours. Whereas today drivers enjoy the continuous use of a divided US 64 East, in the past two lanes and the need to transverse through every little Eastern town plagued the ride. In fact, on a hot Friday in the middle of the summer, it is now often easier and faster to reach Manteo from downtown Raleigh than Atlantic Beach, despite the latter being some thirty miles closer.2 What has changed? Inevitably the force behind the incredible modernization of Northeast North Carolina boils down to Marc Basnight. For over thirty years, Marc Basnight stood in Raleigh as the voice of the Northeast. -

Congressional Directory NEW YORK

214 Congressional Directory NEW YORK THIRTIETH DISTRICT JACK QUINN, Republican, of Hamburg, NY; born on April 13, 1951 in Buffalo, NY; B.A., Siena College, Loudonville, NY, 1973; M.A., State University of New York, Buffalo, 1978; teacher; councilman, Hamburg, 1982±84; town supervisor, Hamburg, 1985±92; founder, DARE, 1984; married the former Mary Beth McAndrews, 1974; two children: Jack III and Kara Eliza- beth; elected on November 3, 1992 to the 103rd Congress; reelected to each succeeding Con- gress. Office Listings 331 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515±3230 .......................... 225±3306 Legislative Director.ÐBeth Meyers. FAX: 226±0347 Legislative Assistants: Cassandra McClam, Michael Pietkiewicz, Aura Kenny, Dan Skopee. Legislative Correspondent.ÐErin Pierce. Brisbane Building, 403 Main Street, Suite 240, Buffalo, NY 14203±2199 ............... (716) 845±5257 Administrative Assistant.ÐMary Lou Palmer. FAX: 847±0323 County: ERIE COUNTY (part); cities and townships of Boston, Brant, Buffalo (part), Cheektowaga, Colden, Concord, Collins, East Aurora, Eden, Elma, Evans, Hamburg, Holland, Lackawanna, Lancaster, North Boston, North Collins, Orchard Park, Sardinia, and Seneca. Population (1990), 580,337. ZIP Codes: 14006, 14010, 14025±27, 14030 (part), 14033±34, 14043, 14047, 14052, 14057, 14059, 14061, 14069, 14070, 14075, 14080, 14085, 14086, 14091, 14110±12, 14127, 14134, 14139±41, 14170, 14201±06, 14208±16, 14218±21, 14223±27, 14263 * * * THIRTY-FIRST DISTRICT AMO HOUGHTON, Republican, of Corning, NY; born in Corning on August 7, 1926; grandson of former Congressman Alanson B. Houghton of New York; graduated, St. Paul's School, Concord, NH; B.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1950; M.A., Harvard Busi- ness School, 1952; honorary doctoral degrees: Alfred University, NY, 1963; Albion College, MI, 1964; Centre College, Danville, KY, 1966; Clarkson College of Technology, Potsdam, NY, 1968; Elmira College, NY, 1982; Hartwick College, Oneonta, NY, 1983; Houghton College, NY, 1983; St.