The Senate 16 Chapter Three: a President Pro Tem Fo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HON. JESSE HELMS ÷ Z 1921–2008

im Line) HON. JESSE HELMS ÷z 1921–2008 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Jesse Helms LATE A SENATOR FROM NORTH CAROLINA MEMORIAL ADDRESSES AND OTHER TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE congress.#15 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office Jesse Helms VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE 43500.002 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) S. DOC. 110–16 Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes HELD IN THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES TOGETHER WITH A MEMORIAL SERVICE IN HONOR OF JESSE HELMS Late a Senator from North Carolina One Hundred Tenth Congress Second Session ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) CONTENTS Page Biography ................................................................................................. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

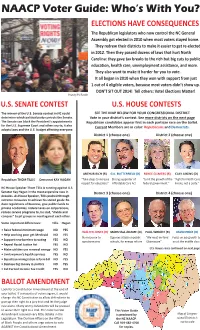

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’S with You?

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’s With You? ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES The Republican legislators who now control the NC General Assembly got elected in 2010 when most voters stayed home. They redrew their districts to make it easier to get re-elected in 2012. Then they passed dozens of laws that hurt North Carolina: they gave tax breaks to the rich but big cuts to public education, health care, unemployment assistance, and more. They also want to make it harder for you to vote. It all began in 2010 when they won with support from just 1 out of 4 eligible voters, because most voters didn’t show up. DON’T SIT OUT 2014! Tell others: Vote! Elections Matter! Photo by Phil Fonville U.S. SENATE CONTEST U.S. HOUSE CONTESTS The winner of the U.S. Senate contest in NC could SEE THE MAP BELOW FOR YOUR CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT determine which political party controls the Senate. Vote in your district’s contest. See more districts on the next page The Senate can block the President’s appointments Republican candidates appear first in each partisan race on the ballot. for the U.S. Supreme Court and other courts; it also Current Members are in color: Republicans and Democrats. adopts laws and the U.S. budget affecting everyone. District 1 (choose one) District 2 (choose one) ARTHUR RICH (R) G.K. BUTTERFIELD (D) RENEE ELLMERS (R) CLAY AIKENS (D) Republican THOM TILLIS Democrat KAY HAGAN “Take steps to increase Strong supporter of “Limit the growth of the “Fight for North Caro- respect for educators” Affordable Care Act federal government.” linians, not a party.” NC House Speaker Thom Tillis is running against U.S. -

105Th Congress 215

NORTH CAROLINA 105th Congress 215 NORTH CAROLINA (Population 1995, 7,195,000) SENATORS JESSE HELMS, Republican, of Raleigh, NC; born in Monroe, NC, October 18, 1921; at- tended Wingate College and Wake Forest College; U.S. Navy, 1942±45; former city editor, Ra- leigh Times; administrative assistant to U.S. Senator Willis Smith, 1951±53, and to U.S. Senator Alton Lennon, 1953; executive director, North Carolina Bankers Association, 1953±60; execu- tive vice president, WRAL±TV and Tobacco Radio Network, 1960±72; member, Raleigh City Council, chairman of Law and Finance Committee, 1957±61; deacon and Sunday School teach- er, Hayes Barton Baptist Church, Raleigh; recipient of two Freedom Foundation awards for radio-television editorials; recipient of annual citizenship awards from North Carolina American Legion, North Carolina Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Raleigh Exchange Club; recipient of Outstanding Service Award of the Council Against Communist Aggression, the Richard Henry Lee Award, and the Order of Lafayette Freedom Award; former trustee, Meredith College, John F. Kennedy College, Delaware Law School, Campbell University, and Wingate College; presi- dent, Raleigh Rotary Club, 1969±70; 33rd degree Mason: Grand Orator, Grand Lodge of Ma- sons of North Carolina, 1964±65, 1982, 1991; member, board of directors, North Carolina Cere- bral Palsy Hospital; member, board of directors of Camp Willow Run, a youth camp for Christ at Littleton, NC; married Dorothy Jane Coble of Raleigh, October 31, 1942; three children: Jane (Mrs. Charles R. Knox), Nancy (Mrs. John C. Stuart), and Charles; seven grandchildren; com- mittees: Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; chairman, Foreign Relations; Rules and Adminis- tration; elected to the U.S. -

The Senate "Two-Hour Rule"

The Senate “Two-Hour Rule” Governing Committee Meeting Times Christopher M. Davis Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process Michael Greene Senior Research Librarian April 20, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45170 The Senate “Two-Hour Rule” Governing Committee Meeting Times Summary Paragraph 5(a) of Senate Rule XXVI, sometimes referred to as the “two-hour rule,” restricts the times that most Senate committees and subcommittees can meet when the full Senate is in session. The rule is intended to help balance the Senate’s committee and floor work and to minimize the logistical conflicts that Senators face between participating in committee hearings and markups and attending to their duties on the chamber floor. Under the terms of the rule, no Senate committee or subcommittee (except the Committees on Appropriations and Budget and their subcommittees) can meet after the Senate has been in session for two hours or past 2:00 p.m. unless one of the following things occur: (1) the Senate grants unanimous consent for them to meet; (2) both the majority and minority leaders (or their designees) agree to permit the meeting, and their agreement has been announced on the Senate floor; or (3) the Senate adopts a privileged motion to allow the meeting. Should a committee meet during a restricted time period without being granted permission, any action that it takes—such as ordering a bill or nomination reported to the Senate—is considered “null, void, and of no effect.” Senate rules restricting committee meeting times have existed for over 70 years and have evolved over time. -

Congressional Directory NEW YORK

214 Congressional Directory NEW YORK THIRTIETH DISTRICT JACK QUINN, Republican, of Hamburg, NY; born on April 13, 1951 in Buffalo, NY; B.A., Siena College, Loudonville, NY, 1973; M.A., State University of New York, Buffalo, 1978; teacher; councilman, Hamburg, 1982±84; town supervisor, Hamburg, 1985±92; founder, DARE, 1984; married the former Mary Beth McAndrews, 1974; two children: Jack III and Kara Eliza- beth; elected on November 3, 1992 to the 103rd Congress; reelected to each succeeding Con- gress. Office Listings 331 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515±3230 .......................... 225±3306 Legislative Director.ÐBeth Meyers. FAX: 226±0347 Legislative Assistants: Cassandra McClam, Michael Pietkiewicz, Aura Kenny, Dan Skopee. Legislative Correspondent.ÐErin Pierce. Brisbane Building, 403 Main Street, Suite 240, Buffalo, NY 14203±2199 ............... (716) 845±5257 Administrative Assistant.ÐMary Lou Palmer. FAX: 847±0323 County: ERIE COUNTY (part); cities and townships of Boston, Brant, Buffalo (part), Cheektowaga, Colden, Concord, Collins, East Aurora, Eden, Elma, Evans, Hamburg, Holland, Lackawanna, Lancaster, North Boston, North Collins, Orchard Park, Sardinia, and Seneca. Population (1990), 580,337. ZIP Codes: 14006, 14010, 14025±27, 14030 (part), 14033±34, 14043, 14047, 14052, 14057, 14059, 14061, 14069, 14070, 14075, 14080, 14085, 14086, 14091, 14110±12, 14127, 14134, 14139±41, 14170, 14201±06, 14208±16, 14218±21, 14223±27, 14263 * * * THIRTY-FIRST DISTRICT AMO HOUGHTON, Republican, of Corning, NY; born in Corning on August 7, 1926; grandson of former Congressman Alanson B. Houghton of New York; graduated, St. Paul's School, Concord, NH; B.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1950; M.A., Harvard Busi- ness School, 1952; honorary doctoral degrees: Alfred University, NY, 1963; Albion College, MI, 1964; Centre College, Danville, KY, 1966; Clarkson College of Technology, Potsdam, NY, 1968; Elmira College, NY, 1982; Hartwick College, Oneonta, NY, 1983; Houghton College, NY, 1983; St. -

11Ir111r1imr F'pdj7'b Volume XVII Number 20 November 9 1998 a STATUS QUO ELECTION THAT DEFIED Senators Running for Re-Election Retained Their Seats

Consortium of Social Science Associations ( ©COSSA 11ir111r1Imr f'PDJ7'B Volume XVII Number 20 November 9 1998 A STATUS QUO ELECTION THAT DEFIED Senators running for re-election retained their seats. HISTORY /-/5 Other new Senators include: former House members Blanche Lincoln (D-AR), who replaces Dale For the Democrats the 1998 mid-term elections Bumpers, and Michael Crapo, (R-ID) who replaces defied history. For first time since 1934 the party Dirk Kempthorne who went home and got elected that held the Presidency did not lose House seats in Governor. an election in the sixth year of a presidential term. By picking up five seats in the House and retaining Leadership Changes for the 1ostti Congress their numbers in the Senate, the Democrats also surpassed expectations from political prognosticators In the Senate, Senator Trent Lott (R-MS) and who predicted small to modest Republican gains in Senator Don Nickles (R-OK) will return to lead their the House and a one to five GOP seat pickup in the party. Newly re-elected Senator Tom Daschle (D Senate. SD) will return as leader of the Democrats. With the retirement of Senator Ford, the number two slot in And yet, viewed from another perspective, the the Senate Democratic leadership opens up. 1998 election did not change much at all. In the House, 98.5 percent of the 401 incumbents who were However, this expected change pales against the on the ballot on November 3 won re-election. Only speculation on the future of the Republican six incumbents lost. Only 17 seats changed parties. -

Department of Transportation and Relat- Ed Agencies Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1998

S. HRG. 105±429 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND RELAT- ED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 1998 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2169/S. 1048 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANS- PORTATION AND RELATED AGENCIES FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 1998, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Department of Transportation General Accounting Office National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) National Transportation Safety Board Nondepartmental witnesses Office of Management and Budget Railroad Retirement Board Surface Transportation Board Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±864 cc WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0±16±056437±9 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. -

Stem Cell Research Hearings

S. HRG. 105±939 STEM CELL RESEARCH HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARING DECEMBER 2, 1998ÐWASHINGTON, DC JANUARY 12, 1999ÐWASHINGTON, DC JANUARY 26, 1999ÐWASHINGTON, DC Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 54±769 cc WASHINGTON : 1999 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0±16±058361±6 1 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. -

The Life of Terry Sanford'

Inside: 'The Life of Terry Sanford' Erskine Bowles honors Sanford THE CHRONICLE letter to The Chronicle. See p. i WEDNESDAY. APRIL 22, 1998 © ONE COPY FREE DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 93, NO. 135 Family, friends, colleagues of Sanford recall fond memories J Former University President stood in a circle, speculating about which one-liner Sanford would have used to Terry Sanford touched the lives of break the silence and ease the tension. mourners who attended his closed- Still in mourning, they joined together with friends to celebrate Sanford's life. casket viewing in the Chapei "Most of the people here today and yesterday afternoon. this evening are from the area or are personal friends," said Sam Poole, long By KATHERINE STROUP time friend ofthe family. "Tomorrow, I Chronicle staffwriter assume there wilt be dignitaries of Inside the Chapel, the mood was state. These are more just some people somber as mourners from across the who were personally touched by him." state sat quietly in their pews, lament And Sanford touched many lives, ED THOMAS/THE CHRONICLE ing the loss of a leader who navigated from his secretaries, who'volunteered Draped in an American flag, Terry Sanford's casket is carried into the Chapel- North Carolina through periods of their nights as babysitters and cam racial unrest, educational strife and paign workers, to the children who contributed far greater to this state ford will leave the University, the state massive industrial growth. Heads bent came of age when Sanford was in his than many other governors, before or and the nation.