Or, Harlequin False Testimony and the Bulletin Magazine's Mythical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

Introduction: Performing Cosmopolitics Chapter 1 (Anti-)Cosmopolitan

Notes Introduction: performing cosmopolitics 1 Unattributed feature article, Australian, 16 September 2000, p. 6. 2 Although the riots resulted directly from a series of locally staged tensions revolving around beach territoriality and male youth culture, the anti-Arab sentiments expressed by demonstrators and circulated by the media tapped into a much wider context of racism provoked by Australia’s participation in the US-led anti-terrorism alliance, the bombings of Australian tourists in Bali by Islamic militants, and a high-profile case of the rape of Caucasian girls by a gang of Lebanese youths in 2002. 3 Federal Government of Australia. (1994) Creative Nation: Common- wealth Cultural Policy. <http://www.nla.gov.au/creative.nation/intro.html> (accessed 19 July 2005). 4 The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 was the cornerstone of the ‘White Australia Policy’ aimed at excluding all non-European migration. The Act was enforced through the use of a dictation test, similar to the one used in South Africa, which enabled authorities to deny entry to any person who was not able to transcribe a passage dictated in a designated European language. The Act remained in force until 1958. 5 Many Australians who voted ‘no’ in fact supported the idea of a republic but did not agree with the only model offered by the ballot. For detailed analysis of the referendum’s results, see Australian Journal of Political Science, 36:2 (2001). 6 See Veronica Kelly (1998a: 9–10) for a succinct overview of significant studies in contemporary Australian theatre -

A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson

'From Mudgee Hills to London Town': A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson On 23 April 1900, at his studio in New Zealand Chambers, Collins Street, Melbourne, John Longstaff began another commissioned portrait. Since his return from Europe in the mid-1890s, when he had found his native Victoria suffering a severe depression, such commissions had provided him with the mainstay to support his young family. While abroad he had studied in the same Parisian atelier as Toulouse Lautrec and a younger Australian, Charles Conder. He had acquired an interest in the new 'plein air' impressionism from another Australian, Charles Russell, and he had been hung regularly in the Salon and also in the British Academy. Yet the successful career and stimulating opportunities Longstaff could have assumed if he had remained in Europe eluded him on his return to his own country. At first he had moved out to Heidelberg, but the famous figures of the local 'plein air' school, like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, had been drawn to Sydney during the depression. Longstaff now lived at respectable Brighton, and while he had painted some canvases that caught the texture and tonality of Australian life-most memorably his study of the bushfires in Gippsland in 1893-local dignitaries were his more usual subjects. This commission, though, was unusual. It had come from J. F. Archibald, editor of the not fully respectable Sydney weekly, the Bulletin, and it was to paint not another Lord Mayor or Chief Justice, First published as the introduction to Brian Kiernan, ed., The Essential Henry Lawson (Currey O'Neil, Kew, Vic., 1982). -

Biographical Information

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION ADAMS, Glenda (1940- ) b Sydney, moved to New York to write and study 1964; 2 vols short fiction, 2 novels including Hottest Night of the Century (1979) and Dancing on Coral (1986); Miles Franklin Award 1988. ADAMSON, Robert (1943- ) spent several periods of youth in gaols; 8 vols poetry; leading figure in 'New Australian Poetry' movement, editor New Poetry in early 1970s. ANDERSON, Ethel (1883-1958) b England, educated Sydney, lived in India; 2 vols poetry, 2 essay collections, 3 vols short fiction, including At Parramatta (1956). ANDERSON, Jessica (1925- ) 5 novels, including Tirra Lirra by the River (1978), 2 vols short fiction, including Stories from the Warm Zone and Sydney Stories (1987); Miles Franklin Award 1978, 1980, NSW Premier's Award 1980. AsTLEY, Thea (1925- ) teacher, novelist, writer of short fiction, editor; 10 novels, including A Kindness Cup (1974), 2 vols short fiction, including It's Raining in Mango (1987); 3 times winner Miles Franklin Award, Steele Rudd Award 1988. ATKINSON, Caroline (1834-72) first Australian-born woman novelist; 2 novels, including Gertrude the Emigrant (1857). BAIL, Murray (1941- ) 1 vol. short fiction, 2 novels, Homesickness (1980) and Holden's Performance (1987); National Book Council Award, Age Book of the Year Award 1980, Victorian Premier's Award 1988. BANDLER, Faith (1918- ) b Murwillumbah, father a Vanuatuan; 2 semi autobiographical novels, Wacvie (1977) and Welou My Brother (1984); strongly identified with struggle for Aboriginal rights. BAYNTON, Barbara (1857-1929) b Scone, NSW; 1 vol. short fiction, Bush Studies (1902), 1 novel; after 1904 alternated residence between Australia and England. -

The Constitution Makers

Papers on Parliament No. 30 November 1997 The Constitution Makers _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1997 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Editors of this issue: Kathleen Dermody and Kay Walsh. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3078 ISSN 1031–976X Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Cover illustration: The federal badge, Town and Country Journal, 28 May 1898, p. 14. Contents 1. Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies 1 The Hon. John Bannon 2. A Federal Commonwealth, an Australian Citizenship 19 Professor Stuart Macintyre 3. The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention 33 Professor Geoffrey Bolton 4. Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican 49 Dr Mark McKenna 5. The High Court and the Founders: an Unfaithful Servant 63 Professor Greg Craven 6. The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? 93 Dr Kathleen Dermody 7. Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament 121 Derek Drinkwater iii Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies* John Bannon s we approach the centenary of the establishment of our nation a number of fundamental Aquestions, not the least of which is whether we should become a republic, are under active debate. But after nearly one hundred years of experience there are some who believe that the most important question is whether our federal system is working and what changes if any should be made to it. -

Randolph the Reckless: Explorations in Australian Masculine Identity, 1889-1941

Randolph the Reckless: Explorations in Australian Masculine Identity, 1889-1941 CHERYL TAYLOR,JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY M. Green remarked that Randolph Bedford was almost as represent ative of the Australia of his day as Lawson or Furphy or Paterson (706). It is certainly the case that from the publication of his earliest Bulletin story inH 1889 until his death in July 1941, Bedford was constantly before the eyes of the Australian reading public. 1 In this essay I argue the view that he principally of fered his contemporaries a paradigm for Australian masculinity. The paradigm operated in the areas of male with male and male with female relationships, as well as in the political and financial spheres. Green's sense of Bedford as a writer of the 1890s can be supported, since it was in this decade and during Federation that his influence was paramount and most original. He offered extreme or ex panded versions of masculine gender norms, sometimes resisting and at other times anticipating innovation. Aspects of the Bedford model persist in current concepts of Australian masculinity. The model was embattled from the beginning, and increasingly vulnerable. In the decades before World War I, Bedford exemplified an extreme masculine au tonomy, based on his exploits as a journalist and mining entrepreneur in the out back and in Europe. He projected this image in the club and pub world of male interchange, which was his natural habitat, and which defined itself in the period as Bohemian and atheistic, against the opposing parameters of suburban respon� sibility and female and clerical support for temperance. -

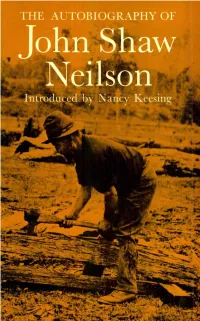

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY of John Shaw Neilson Introduced by Nancy Keesing the AUTOBIOGRAPHY of John Shaw Neilson

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF John Shaw Neilson Introduced by Nancy Keesing THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF John Shaw Neilson Introduced by NANCY KEESING National Library of Australia 1978 Neilson, John Shaw, 1872-1942. The autobiography of John Shaw Neilson; introduced by Nancy Keesing.—Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1978.— 175 p.; 22 cm. Index. Bibliography: p. 174-175. ISBN 0 642 99116 2. ISBN 0 642 99117 0 Paperback. 1. Neilson, John Shaw, 1872-1942. 2. Poets, Australian—Biography. I. National Library of Australia. II. Title. A821'.2 First published in 1978 by the National Library of Australia © 1978 by the National Library of Australia Edited by Jacqueline Abbott Designed by Derrick I. Stone Dustjacket/cover illustration from a photograph, 'Life in the Bush', by an unknown photographer Printed and bound in Australia by Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, Melbourne Contents Preface 7 Introduction by Nancy Keesing 11 The Autobiography of John Shaw Neilson 29 Early Rhymning and a Setback 31 Twelve Years Farming 58 Twelve Years Farming [continued] 64 The Worst Seven Years 90 The Navvy with a Pension 120 Six Years in Melbourne 146 Notes 160 Bibliography 174 Preface In 1964 the National Library of Australia purchased a collection of Neilson material from a connoisseur of literary Australiana, Harry F. Chaplin. Chaplin had bound letters, memoranda and manuscripts of the poet John Shaw Neilson into volumes, grouped according to content, and in the same year had published a guide to the collection. One of these volumes contained Shaw Neilson's autobiography, transcribed from his dictation by several amanuenses, who compensated for his failing sight. -

Copyright Sources for Australian Drama and Film Richard Fotheringham Many Early Australian Play Scripts Have Survived Only Because of Stage Censorship

Copyright Sources For Australian Drama and Film Richard Fotheringham Many early Australian play scripts have survived only because of stage censorship. Such manuscripts have been retained in files in the Australian Archives’ copyright files. The author outlines some of his more interesting discoveries during his research, and describes how to proceed to view them. One of the side benefits of the otherwise dubious practice of stage censorship is that it was an excellent way of ensuring that scripts of performed plays were preserved for posterity. It is because of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office in London, for example, that complete manuscripts of two of the most important Australian plays of the nineteenth century George Darrell’s The Sunny South and Alfred Dampier and Garnet Walch’s stage version of Robbery Under Arms — were preserved in the British Library and eventually published in modern critical editions.1 The British censorship system became involved because both plays had at different times been staged in London, as were several other Australian plays held in this collection. It has usually been assumed that the survival of unpublished playtexts performed only in Australia, after the early attempts at censorship, was a far less regular or regulated business, and that we are faced with the almost total disappearance of the plays of several vigorous and exciting ages of Australian drama, including significant works written as recently as the 1930s. It is not just stage history which is impoverished by the loss of these texts, for the live stage has always been a place where the Australian language, its slang and colloquialisms, is quickly picked up; and a place too where contemporary ideas about nationhood, nationalism, aboriginal people, ethnic minorities, the role of women in Australian society, the Australian identity, war, the bush and the city etc, have been freely discussed. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1941

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly WEDNESDAY, 20 AUGUST 1941 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 4 Election of Speaker. [ASSEMBLY.] Governor's Opening Speech. WEDNESDAY, 20 AUGUST, 1941. PRESENTATION OF MR. SPEAKER. Mr. SPEAKER (Hon. E. J. Hanson, Buranda) took the chair at 9.45 a.m., and said: Under Standing Order No. 8 I shall now proceed to Government House, there to present myself to His Excellency the Governor as the member chosen to fill the high and honourable office of Speaker, and I invite such hon. members as care to do so to accompany me. Mr. SPEAKER then left the chair. The House resuming at three minutes to 12 o'clock, Mr. SPEAKER said: I have to report that I have this day presented myself to His Excellency the Governor at Government House, as the member chosen to fill the high and honourable office of Speaker of this House, and that His Excellency was pleased to congratulate me upon my election. Honourable Members: Hear, hear! GOVERNOR'S OPENING SPEECH. At noon His Excellency the Governor came to Parliament House, was announced by the Sergeant-at-Arms, received by Mr. Speaker (Hon. E. J. Hanson) at the bar, and accompanied to the dais. Hon. members being seated, His Excellency read the following Opening Speech:- ''GENTLEMEN OF THE PARLIAMENT OF QUEENS LAND,- '' In these days of unparalleled danger to the British Commonwealth of Nations, and to free peoples everywhere, it is pleasing to be able to meet you at the opening of this, the first session of the twenty-ninth Parliament of Queensland. -

![[The Poetical Works of Randolph Bedford]. Melbourne, Troedell's Printery, [1902]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8689/the-poetical-works-of-randolph-bedford-melbourne-troedells-printery-1902-6808689.webp)

[The Poetical Works of Randolph Bedford]. Melbourne, Troedell's Printery, [1902]

RANDOLPH BEDFORD (1868-1941) A BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Ross Smith and Cheryl Frost I. PUBLICATIONS A. EDITIONS Poetry [The poetical works of Randolph Bedford]. Melbourne, Troedell's Printery, [1902]. Fiction True eyes and the whirlwind. London, Duckworth, 1903. The snare of strength. London, Heinemann, 1905. Billy Pagan, mining engineer. With four illustrations by Percy F.S. Spence, Sydney, N.S.W. Bookstall Co., 1911; 1921. The silver star. Illustrations by John P. Davis. Sydney, N.S.W. Bookstall Co., 1917. Aladdin and the boss cockie. Drawings by Percy Lindsay. Sydney, N.S.W. Bookstall Co., 1920. A story of mateship. Brisbane, The Worker, 1936. Articles Ojeensland, the winter paradise of Australasia. III. pp. 16 8vo. Brisbane, [1906]. Explorations in civilisation. Sydney, Day, [1916]. (b) Extract on Italian engineers. SYDNEY MAIL May 13, 1914, P. 44. Autobiography Naught to thirty-three. Sydney, Currawong Pub. Co., 1944. New edition with a foreword by Geoffrey Blainey. Melbourne University Press, 1976. 106 B. SHORT STORIES, POEMS, ARTICLES, SKETCHES, LETFERS, ETC. 11. Jepson's fortune [short story]. BULLETIN December 21, 1889, 9-10. 12. The vengeance of Ruby Julia [short story]. BULLETIN July 19, 1890, 18. 13. Why Graveson died [short story]. BULLETIN Decem- ber 13, 1890, 8. 14. The cry of a clod [poem]. BULLETIN November 19, 1892, 17. 15. A piece of woman nature [short story]. BULLETIN January 28, 1893, 17. 16. Advts in verse [article]. BULLETIN March 11, 1893, 17. Reprinted BULLETIN March 9, 1932, 23. 17. The retail brand of gentleman [anecdote]. BULLETIN September 30, 1893, 19. 18. In the train - Melbourne to Richmond [poem]. -

Two Hundred Years of Australian Crime Fiction Doi: Https:Doi.Org/10.7358/Ling-2017-002-Knig [email protected]

Stephen Knight University of Melbourne From Convicts to Contemporary Convictions: Two Hundred Years of Australian Crime Fiction DOI: https:doi.org/10.7358/ling-2017-002-knig [email protected] Australia the great southern continent was named in European mode from the Latin for southern, ‘australis’. The English used it first for European purposes, from 1788 as a base for convicts they did not want to execute, now independent America had rejected this role – and also as a way of ensuring other European powers did not gain control of what seemed likely to be a major source of valu- able resources 1. Those manoeuvres were simplified by the refusal to treat in political or territorial terms with the Indigenous people, who in many tribes with many languages had been in Australia for thousands of years, and by the insistence on seeing the country as Terra Nullius, ‘the land of nobody’, so theorizing the theft of the massive continent. The white taking of Australia is an action that is only after two hundred years slowly being examined, acknowledged and even more slowly compensated for, and the invasion-related but long-lasting criminal acts against Indigenes are only in the last decades beginning to emerge in Australian crime fiction, as will be discussed later. But criminalities familiar to nineteenth and twentieth-century Europeans were always a presence in popular Australian literature, revealing over time varying attitudes to order and identity in the developing country, and taking paths that can seem very different from those of other countries. The criminographical genre and Australia had an early relationship when both local and London publishers described the bold distant dramas, as in 1 This is an invited essay. -

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL Journal VOLUME 855 NO. 2 DECEMBER 2014 The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history published twice yearly by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria. The Royal Historical Society of Victoria acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government through Arts Victoria—Department of Premier and Cabinet. Publication of this edition of the Victorian Historical Journal is made possible with the support of the estate of the late Edward Wilson. Cover: Bust of Justice Thomas Fellows (Courtesy of Supreme Court of Victoria.) Sculptor: James Scurry VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Volume 85, Number 2 December 2014 Articles Sincere Thanks ....................Richard Broome and Marilyn Bowler 185 Introduction............................................................Marilyn Bowler 186 Exodus and Panic? Melbourne’s Reaction to the Bathurst Gold Discoveries of May 1851 ...............Douglas Wilkie 189 The Birth of the Melbourne Cricket Club: a New Perspective on its Foundation Date.................Gerald O’Collins and David Webb 219 The Point Hicks Controversy: the Clouded Facts ............................................................................Trevor Lipsombe 233 Charles La Trobe and the Geelong Keys.....................Murray Johns 254 Attempts to Deal with Thistles in Mid-19th Century Victoria..............................................................John Dwyer 276 So New and Exotic! Gita Yoga in Australia from the 1950s to Today. ...............................................Fay