Randolph the Reckless: Explorations in Australian Masculine Identity, 1889-1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2013-228 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989 — section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister 04 September 2013 Page 1 of 7 Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Division of Lawson: Henry Lawson’s Australia NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bellbird Loop Crested Bellbird ‘Bellbird’ is a name given in Australia to two endemic (Oreoica gutturalis) species of birds, the Crested Bellbird and the Bell-Miner. The distinctive call of the birds suggests Bell- Miner the chiming of a bell. Henry Kendall’s poem Bell Birds (Manorina was first published in Leaves from Australian Forests in melanophrys) 1869: And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing, The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing. The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time! They sing in September their songs of the May-time; Billabong Street Word A ‘billabong’ is a pool or lagoon left behind in a river or in a branch of a river when the water flow ceases. The Billabong word is believed to have derived from the Indigenous Wiradjuri language from south-western New South Wales. The word occurs frequently in Australian folk songs, ballads, poetry and fiction. -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

Introduction: Performing Cosmopolitics Chapter 1 (Anti-)Cosmopolitan

Notes Introduction: performing cosmopolitics 1 Unattributed feature article, Australian, 16 September 2000, p. 6. 2 Although the riots resulted directly from a series of locally staged tensions revolving around beach territoriality and male youth culture, the anti-Arab sentiments expressed by demonstrators and circulated by the media tapped into a much wider context of racism provoked by Australia’s participation in the US-led anti-terrorism alliance, the bombings of Australian tourists in Bali by Islamic militants, and a high-profile case of the rape of Caucasian girls by a gang of Lebanese youths in 2002. 3 Federal Government of Australia. (1994) Creative Nation: Common- wealth Cultural Policy. <http://www.nla.gov.au/creative.nation/intro.html> (accessed 19 July 2005). 4 The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 was the cornerstone of the ‘White Australia Policy’ aimed at excluding all non-European migration. The Act was enforced through the use of a dictation test, similar to the one used in South Africa, which enabled authorities to deny entry to any person who was not able to transcribe a passage dictated in a designated European language. The Act remained in force until 1958. 5 Many Australians who voted ‘no’ in fact supported the idea of a republic but did not agree with the only model offered by the ballot. For detailed analysis of the referendum’s results, see Australian Journal of Political Science, 36:2 (2001). 6 See Veronica Kelly (1998a: 9–10) for a succinct overview of significant studies in contemporary Australian theatre -

A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson

'From Mudgee Hills to London Town': A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson On 23 April 1900, at his studio in New Zealand Chambers, Collins Street, Melbourne, John Longstaff began another commissioned portrait. Since his return from Europe in the mid-1890s, when he had found his native Victoria suffering a severe depression, such commissions had provided him with the mainstay to support his young family. While abroad he had studied in the same Parisian atelier as Toulouse Lautrec and a younger Australian, Charles Conder. He had acquired an interest in the new 'plein air' impressionism from another Australian, Charles Russell, and he had been hung regularly in the Salon and also in the British Academy. Yet the successful career and stimulating opportunities Longstaff could have assumed if he had remained in Europe eluded him on his return to his own country. At first he had moved out to Heidelberg, but the famous figures of the local 'plein air' school, like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, had been drawn to Sydney during the depression. Longstaff now lived at respectable Brighton, and while he had painted some canvases that caught the texture and tonality of Australian life-most memorably his study of the bushfires in Gippsland in 1893-local dignitaries were his more usual subjects. This commission, though, was unusual. It had come from J. F. Archibald, editor of the not fully respectable Sydney weekly, the Bulletin, and it was to paint not another Lord Mayor or Chief Justice, First published as the introduction to Brian Kiernan, ed., The Essential Henry Lawson (Currey O'Neil, Kew, Vic., 1982). -

Chapter 4. Australian Art at Auction: the 1960S Market

Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Shireen huda Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/pedigree_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Author: Huda, Shireen Amber. Title: Pedigree and panache : a history of the art auction in Australia / Shireen Huda. ISBN: 9781921313714 (pbk.) 9781921313721 (web) Notes: Includes index. Bibliography. Subjects: Art auctions--Australia--History. Art--Collectors and collecting--Australia. Art--Prices--Australia. Dewey Number: 702.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: John Webber, A Portrait of Captain James Cook RN, 1782, oil on canvas, 114.3 x 89.7 cm, Collection: National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. Purchased by the Commonwealth Government with the generous assistance of Robert Oatley and John Schaeffer 2000. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements -

Biographical Information

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION ADAMS, Glenda (1940- ) b Sydney, moved to New York to write and study 1964; 2 vols short fiction, 2 novels including Hottest Night of the Century (1979) and Dancing on Coral (1986); Miles Franklin Award 1988. ADAMSON, Robert (1943- ) spent several periods of youth in gaols; 8 vols poetry; leading figure in 'New Australian Poetry' movement, editor New Poetry in early 1970s. ANDERSON, Ethel (1883-1958) b England, educated Sydney, lived in India; 2 vols poetry, 2 essay collections, 3 vols short fiction, including At Parramatta (1956). ANDERSON, Jessica (1925- ) 5 novels, including Tirra Lirra by the River (1978), 2 vols short fiction, including Stories from the Warm Zone and Sydney Stories (1987); Miles Franklin Award 1978, 1980, NSW Premier's Award 1980. AsTLEY, Thea (1925- ) teacher, novelist, writer of short fiction, editor; 10 novels, including A Kindness Cup (1974), 2 vols short fiction, including It's Raining in Mango (1987); 3 times winner Miles Franklin Award, Steele Rudd Award 1988. ATKINSON, Caroline (1834-72) first Australian-born woman novelist; 2 novels, including Gertrude the Emigrant (1857). BAIL, Murray (1941- ) 1 vol. short fiction, 2 novels, Homesickness (1980) and Holden's Performance (1987); National Book Council Award, Age Book of the Year Award 1980, Victorian Premier's Award 1988. BANDLER, Faith (1918- ) b Murwillumbah, father a Vanuatuan; 2 semi autobiographical novels, Wacvie (1977) and Welou My Brother (1984); strongly identified with struggle for Aboriginal rights. BAYNTON, Barbara (1857-1929) b Scone, NSW; 1 vol. short fiction, Bush Studies (1902), 1 novel; after 1904 alternated residence between Australia and England. -

The Constitution Makers

Papers on Parliament No. 30 November 1997 The Constitution Makers _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1997 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Editors of this issue: Kathleen Dermody and Kay Walsh. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3078 ISSN 1031–976X Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Cover illustration: The federal badge, Town and Country Journal, 28 May 1898, p. 14. Contents 1. Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies 1 The Hon. John Bannon 2. A Federal Commonwealth, an Australian Citizenship 19 Professor Stuart Macintyre 3. The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention 33 Professor Geoffrey Bolton 4. Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican 49 Dr Mark McKenna 5. The High Court and the Founders: an Unfaithful Servant 63 Professor Greg Craven 6. The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? 93 Dr Kathleen Dermody 7. Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament 121 Derek Drinkwater iii Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies* John Bannon s we approach the centenary of the establishment of our nation a number of fundamental Aquestions, not the least of which is whether we should become a republic, are under active debate. But after nearly one hundred years of experience there are some who believe that the most important question is whether our federal system is working and what changes if any should be made to it. -

Better Half-Dead Than Read? the Mezzomorto Cases and Their Implications for Literary Culture in the 1930S

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Goldsmith, Ben (1998) Better half-dead than read? The Mezzomorto cases and their implications for literary culture in the 1930s. In Australian Literature and the Public Sphere, 1998-07-03 - 1998-07-07. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/78437/ c Copyright 1998 [please consult the author] This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Better Half-Dead than Read? The Mezzomorto Cases and their Implications for Literary Culture in the 1930si BEN GOLDSMITH, GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY This article focusses on the two libel cases arising from Brian Penton's review of Vivian Crockett's novel Mezzomorto for the Bulletin in 1934, viewing them as points of entry into Australian literary politics in the 1930s, and as windows on to one of the most enduring and interesting feuds in Australian literary culture, that between P.R. -

Lionel Lindsay

Lionel Lindsay Lionel Lindsay The Printmakers’ Printmaker Lionel Lindsay The Printmakers’ Printmaker Written by Robert C. Littlewood Published by PTY DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS LTD First Edition Standard version: 1000 copies bound in wrappers De luxe version: 150 signed copies + 10 for presentation Casebound in cloth with orginal print and deluxe supplement First Published January 2011 PTY DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS LTD PO Box 272 Prahran Melbourne Victoria 3181 Australia +61 3 9510 8484 [email protected] www.DouglasStewart.com.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other informational storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: Standard Version: 1 905611 53 6 978 1 905611 53 9 De Luxe Version: 1 905611 54 4 978 1 905611 54 6 Photography: James Calder, ACME Photographics Tira Lewis Photography Design: Tira Lewis Text: Robert C. Littlewood Design & Format: Douglas Stewart Fine Books Pty Ltd Standard Version Front cover: Item 71 Back Cover: Item 99 The Lindsay family needs little introduction to anyone familiar with the history of Australian art. A family of ten children produced five distinguished artists, each contributing to the foundations of art on this continent. Dr. Robert Charles Alexander Lindsay and Jane Elizabeth Williams were married in 1868 in Creswick, Victoria, where they settled to rear and educate their family. Creswick at this time was a gold mining boom-town and Dr. Lindsay was one of four practicing physicians in the town. -

AUSTRALIAN ETCHINGS & ENGRAVINGS S

ART GALLERY NSW AUSTRALIAN ETCHINGS & ENGRAVINGS s – s FROM THE GALLERY’S COLLECTION Art Gallery of New South Wales 5 May to 22 July 2007 INTRODUCTION This exhibition presents Australian etchings, engravings and groups, such as the Australian Painter Etchers’ Society were wood engravings from the Gallery’s collection, made between established – the Painter Etchers ran for over twenty years from the 1880s and 1930s. These decades saw a sustained period of 1921, providing a forum for the exhibition of artists’ prints, creativity, energy and activity in Australian art when artists’ prints classes in etching and a collectors’ club. began to invite serious engagement by artists and critics for the Artists’ prints attained a higher profile with the public. first time, attaining a new status among artists, critics, dealers In Britain, prints had developed a huge following with attendant and the collecting public. societies, publishers, dealers and publications. Hundreds of artists Mirroring the European etching revival of the 19th century, made prints for the first time to take advantage of a buoyant the 1880s saw the emergence of the ‘Painter-etcher’ in Australia market for prints; etchings in particular had achieved rapid – artists who produced prints as original works of art, inspired by escalations in price for the work of the most popular artists – ‘art for art’s sake’. Their work contrasted with the more familiar there were even instances of financial speculation on published reproductive prints of the preceding century which had been editions. Locally, there were similar developments, albeit on a created by skilled artisans interpreting the work of others to smaller scale. -

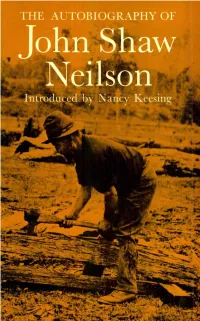

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY of John Shaw Neilson Introduced by Nancy Keesing the AUTOBIOGRAPHY of John Shaw Neilson

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF John Shaw Neilson Introduced by Nancy Keesing THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF John Shaw Neilson Introduced by NANCY KEESING National Library of Australia 1978 Neilson, John Shaw, 1872-1942. The autobiography of John Shaw Neilson; introduced by Nancy Keesing.—Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1978.— 175 p.; 22 cm. Index. Bibliography: p. 174-175. ISBN 0 642 99116 2. ISBN 0 642 99117 0 Paperback. 1. Neilson, John Shaw, 1872-1942. 2. Poets, Australian—Biography. I. National Library of Australia. II. Title. A821'.2 First published in 1978 by the National Library of Australia © 1978 by the National Library of Australia Edited by Jacqueline Abbott Designed by Derrick I. Stone Dustjacket/cover illustration from a photograph, 'Life in the Bush', by an unknown photographer Printed and bound in Australia by Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, Melbourne Contents Preface 7 Introduction by Nancy Keesing 11 The Autobiography of John Shaw Neilson 29 Early Rhymning and a Setback 31 Twelve Years Farming 58 Twelve Years Farming [continued] 64 The Worst Seven Years 90 The Navvy with a Pension 120 Six Years in Melbourne 146 Notes 160 Bibliography 174 Preface In 1964 the National Library of Australia purchased a collection of Neilson material from a connoisseur of literary Australiana, Harry F. Chaplin. Chaplin had bound letters, memoranda and manuscripts of the poet John Shaw Neilson into volumes, grouped according to content, and in the same year had published a guide to the collection. One of these volumes contained Shaw Neilson's autobiography, transcribed from his dictation by several amanuenses, who compensated for his failing sight.