The Susquehanna Review 2011/2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

CHAPTER PAGE the Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland

The Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland 1 CHAPTER PAGE The Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this The Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland 2 eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Tyranny of the Dark Author: Hamlin Garland Release Date: January 8, 2008 [EBook #24220] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TYRANNY OF THE DARK *** Produced by Jeannie Howse, David Yingling, David Garcia, Bethanne M. Simms and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.) * * * * * +-----------------------------------------------------------+ | Transcriber's Note: | | | | Inconsistent hyphenation in the original document has | | been preserved. | | | | Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. For | | a complete list, please see the end of this document. | | | +-----------------------------------------------------------+ * * * * * [Illustration: See p. 243 "SHE CAME SLOWLY, WITH ONE SLIM HAND ON THE RAILING"] THE TYRANNY OF THE DARK The Tyranny of the Dark, by Hamlin Garland 3 BY HAMLIN GARLAND AUTHOR OF "THE CAPTAIN OF THE GRAY-HORSE TROOP" "HESPER" "THE LIGHT OF THE STAR" ETC. ETC. [Illustration] LONDON AND NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS :: MCMV Copyright, 1905, by HAMLIN GARLAND. All rights reserved. Published May, 1905. CONTENTS BOOK I CHAPTER PAGE 4 CHAPTER PAGE I. -

Ensington May – August 2020

ENSINGTON MAY – AUGUST 2020 – AUGUST MAY May 2 New Releases June 17 New Releases July 32 New Releases August 46 New Releases Citadel Press 61 Backlist 72 Rights Guide 82 Kensington Sub-Agents 84 Index 85 Ordering Information 86 THE PERFECT DAUGHTER Joseph Souza Joseph Souza’s third riveting novel of domestic suspense about a mother who is unwittingly drawn into the dark underbelly of her picture-perfect Maine town… With The Neighbor and Pray for the Girl, Joseph Souza proved himself a master of twisty and unpredictable psychological Suspense. This riveting new novel takes place on Shepherd’s Bay, home to generations of lobstermen and their families. Lately, affluent newcomers have been buying up waterfront property and mingling uneasily with the locals. Tensions are high, especially since Dakota James, a teenage boy from the wealthier side of Town, disappeared weeks ago. But another disturbing incident soon follows. When high school junior Katie Eaves and her friend, Willow Briggs, fail to come home after a night out, Katie’s mother, Isla, is frantic. Two agonizing days go by before Katie is found, bruised and bloodied, yet alive. Isla is grateful. But Willow, a wealthy newcomer from Los Angeles, is still missing. And Katie can’t remember anything about the night of their disappearance. Isla tries to help her daughter sort through her hazy recollections, and to recall the truth of her tangled friendship with privileged, beautiful Willow. At the hair salon she owns, Isla hears dark whispers about wild parties, drug deals, and love triangles gone wrong. How much truth is in the gossip? Is Dakota’s disappearance linked to the others? And what other shocking secrets lie at the heart of Shepherd’s Bay—and of the family Isla is struggling to hold together? Category: Fiction ISBN13: 978-1-4967-2638-4 Praise for Joseph Souza U.S./Canadian Price: $26.00/$35.00 “A complex tale of malice and mayhem, suspenseful and loaded with misdirection and surprising plot Rights: World twists. -

MOVIE SUMMARY (The Count of Monte Cristo) in the Turbulent Days in Which France Was Transitioning Away from Napoleonic Rule

MOVIE SUMMARY (The count of Monte Cristo) In the turbulent days in which France was transitioning away from Napoleonic rule, Edmond Dantes (Caviezel) and his closest friend, Fernand Mondego (Pearce), aspire to gain the same two things: the next captaincy of a ship in Morel's (Godfrey) Marseille-based shipping business and the hands of the lovely Mercedes Iguanada (Dominczyk). Dantes and Mondego are diverted to Elba on a shipping mission because their captain requires medical attention. Assistance comes, unexpectedly, in the form of the personal physician of the exiled Napoleon (Norton). In return for the use of his doctor, Napoleon demands that Dantes deliver a letter for him and that the mission and the letter be kept a secret. Unknown to the illiterate Dantes, the letter will provide Bonapartists in Marseille information of pertinence to a possible rescue of Napoleon. Also unknown to him, Fernand has discovered and read the letter and has full knowledge of its contents. On his return to France, Dantes's fortunes peak as Morel names him captain of one of his ships and an improved station in life prompts Edmond to propose to Mercedes, who accepts the offer. In the process of being beaten out of the two things that matter most to him in life, the jealous Fernand knows that the letter Dantes is carrying can be used to falsely implicate him in an act that might be viewed by local authorities as treasonous. Fernand, and his confidant, shipping colleague Danglars (Woodington), betray Dantes by making the magistrate Villefort (Frain) aware of the letter. -

Cultivating Happiness & Sanity in Trying Times

CULTIVATING HAPPINESS AND SANITY IN TRYING TIMES VAJRAYANA INSTITUTE SYDNEY VEN ROBINA COURTIN SEPTEMBER 10–13, 2020 CONTENTS 1. Everything is Transitory 4 2. We Create Our Own Reality: the Natural Law of Karma 8 3. There’s No Karma That Can’t Be Purified 23 4. There’s Nothing Better than Purification! 46 5. Unravelling Our Emotions 50 6. There’s Nothing to Be Attached To 66 7. Meditate on the Clear Nature of Your Mind 74 8. Equanimity, the Basis of Love and Compassion 84 9. Our Life Belongs to Sentient Beings 92 10. How We Grasp at a Separate Self 102 These teachings have been prepared for the participants in the teachings at Vajrayana Institute, Sydney, Australia, September 10–13, 2020 with Ven Robina Courtin. vajrayana.com.au Thanks for the teachings in chapters 1, 4, 6, 9 and 10 to Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive lamayeshe.com and to Wisdom Publications for the teachings in chapter 7 wisdomexperience.org. Photo Shayamuni Buddha painting (original in colour) by Jane Seidlitz. 3 1. EVERYTHING IS TRANSITORY LAMA ZOPA RINPOCHE SEE ALL PHENOMENA AS A STAR, A FLAME, DEW, A WATER BUBBLE, A DREAM, LIGHTNING, A CLOUD Look at all the causative phenomena: I, body, mind; friend, enemy, stranger; all the possessions, all the surrounding people; look at them like a shooting star the star is there, then the next minute when you look, it’s not there. All these causative phenomena, including power, reputation and so forth, all these things, are in the nature of being transitory. Like a flame. -

American University Library

ARTIFACTS By Lesley Ward Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing Chair: (XkJAL jJL tu * c - Denise Orenstein Kermit Moyer Dean of the College Date 2007 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1445572 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1445572 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ARTIFACTS BY Lesley Ward ABSTRACT Artifacts is an original collection of short stories that examines what occurs when a group of ordinary people are forced to reconcile their past lives with the present. The characters must excavate the past, whether it is motivated by the discovery of an estranged wife’s silk scarf or the hush of a calm lake. -

A London Life; the Patagonia; the Liar; by Henry James 1

A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; by Henry James 1 A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; by Henry James The Project Gutenberg EBook of A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; Mrs. Temperly, by Henry James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; Mrs. Temperly Author: Henry James Release Date: May 17, 2008 [EBook #25500] A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; by Henry James 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A LONDON LIFE ET AL. *** Produced by David Edwards, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) A LONDON LIFE AND OTHER TALES [Illustration: Publisher's logo] A LONDON LIFE THE PATAGONIA THE LIAR MRS. TEMPERLY BY HENRY JAMES London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1889 COPYRIGHT 1889 BY A London Life; The Patagonia; The Liar; by Henry James 3 HENRY JAMES CONTENTS PAGE A LONDON LIFE 1 THE PATAGONIA 159 THE LIAR 241 MRS. TEMPERLY 317 NOTE The last of the following four Tales originally appeared under a different name. A LONDON LIFE I It was raining, apparently, but she didn't mind--she would put on stout shoes and walk over to Plash. -

LCSH Section F

F (Computer program language) F-117 (Jet attack plane) (Not Subd Geog) — Spectra BT Programming languages (Electronic UF F-117 (Jet fighter plane) [Former heading] F-t-Ms (Female-to-male transsexuals) computers) Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk (Jet attack plane) USE Female-to-male transsexuals UF F-Sharp (Computer program language) Night Hawk (Jet attack plane) f-value BT Functional programming languages Nighthawk (Jet attack plane) USE Oscillator strengths Object-oriented programming languages Stealth fighter F.XX (Transport plane) F.1 (Jet fighter plane) BT Attack planes USE Fokker F.XX (Transport plane) USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Lockheed aircraft F1 cars F.2 (Seaplane) Stealth aircraft USE Formula One automobiles USE Felixstowe F.2 (Seaplane) F-117 (Jet fighter plane) F2A Buffalo (Fighter plane) F.2A (Seaplane) USE F-117 (Jet attack plane) USE Buffalo (Fighter plane) USE Felixstowe F.2 (Seaplane) F/A-18 (Jet fighter plane) F2H (Jet fighter plane) F.4 (Fighter plane) USE Hornet (Jet fighter plane) USE Banshee (Jet fighter plane) USE Martinsyde Buzzard (Fighter plane) F/A-18 E/F (Jet fighter plane) F2Ms (Female-to-male transsexuals) F-4 (Jet fighter plane) USE Hornet (Jet fighter plane) USE Female-to-male transsexuals USE Phantom II (Jet fighter plane) F/A-22 (Jet fighter plane) F3 automobiles F-5 (Jet fighter plane) (Not Subd Geog) USE F-22 (Jet fighter plane) USE Formula Three automobiles UF Freedom Fighter (Jet fighter plane) F.B.19 (Fighter plane) F3D (Jet fighter plane) BT Jet fighter planes USE Vickers F.B.19 (Fighter plane) USE Skyknight (Jet fighter plane) F-5 E (Jet fighter plane) F.B.A. -

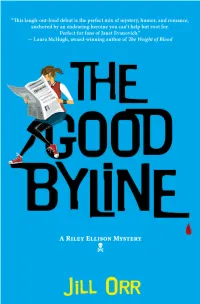

The Good Byline

Advance Praise “ Jill Orr’s delightful, laugh-out-loud debut is the perfect mix of mystery, humor, and romance, anchored by an endearing heroine you can’t help but root for. A fun, fast- paced read with a satisfying mystery at its heart. Perfect for fans of Janet Evanovich.” — Laura McHugh, award-winning author of Arrowood and The Weight of Blood “ Riley ‘Bless -Her-Heart’ Ellison is a breath of fresh air—a funny, empathic, Millennial heroine. She kept me turning the pages well into the night.” — Susan M. Boyer, USA TODAY–bestselling author of the Liz Talbot mystery series “Who knew obituaries could be this much fun?” — Gretchen Archer, USA TODAY–bestselling author of the Davis Way Crime Caper series “ Jill Orr’s Tuttle Corner is absolutely charming, and you’ll want to hang out more in this Virginian small town with Riley and her cast of friends. The methodical local reporter, Will Holman, is a standout, and here’s hoping he will appear in more of Riley’s mystery adventures. Fans of Hannah Dennison’s Vicky Hill series will devour this debut!” — Naomi Hirahara, Edgar Award–winning author of the Mas Arai and Ellie Rush mystery series “An extremely fun read! Regina H., Personal Romance Concierge, may be my favorite new literary character of the decade.” — Anne Flett-Giordano, author of Marry, Kiss, Kill and Emmy-winning writer of Mom, Frasier, and Desperate Housewives “ Jill Orr will make you laugh, make you think, and steam up your reading glasses with this funny, smart, and romantic mystery debut. The Good Byline is an engaging story that will keep readers wondering whodunit and how’d-they-do- it until the very end.” —Diane Kelly, award-winning author of the Death & Taxes and Paw Enforcement mysteries “ In this irresistible page-turner, Jill Orr delivers a funny, smartly written mystery featuring a charming heroine and appealing setting. -

The Clinton Independent

The Clinton Independent. VOL. XXXV.—NO. 36. ST. JOHNS, MICH., THURSDAY, JUNE 27, 1901. WHOLE NO—1807 thing always grieved us. Tiie church A (I00D MAN GONE. trustees always removed all tlie church THE TENTCATERRILLAR cushions from tiie seats Monday morn Death of an Old Resident and Influential ings, for we never could have paid for Becoming Very Plentiful and Very Dis new ones. All were removed except Citizen. from two pews in the center of tiie astrous to Our Orchard*. W. W. Brainard died after a linger Very Enjoyable Occasion at the church where they were fastened, and The Auditorium and Galleries Mr. R. R. Rlsley, of Bengal town Two Prominent Young Business ing illness at an early hour, Wednes no one sat there. We knew then how ship. informs us that tiie caterpillars Men and Two of St. Johns' day morning, June 26, at tiie family Home of Mr- and Mrs. to sympathize witli our forefathers of the M. E- Church are becoming very numerous and work residence, aged 77 years. Funeral E- H- Lyon. who attended school under like condi Crowded. ing great damage to orchards. They Fairest Daughters services will be held at the house Fri tions. appear to be more plentiful thisseason day afternoon at 4 o ’clock. So much sanctity had a sad effect than ever before. Sir. Brainard was born in Keen, upon a few. One wayward girl stuck He says tiie eggs are deposited upon Cheshire county, N. II., May 16, 1824. a pin into the back of a seat in front the limb in a short space and covered Tiie family moved over the mountains AN INTERESTING PROGRAM of her. -

Contemporary Bulgarian Writers

Contemporary Bulgarian Writers Contemporary Bulgarian Writers 1 Проектът е реализиран с финансовата подкрепа на Национален фонд Култура. Contemporary Bulgarian Writers Compilers: Svetlozar Zhelev, Director of the National Book Centre The Advisory Board: Prof. Dr. Amelia Licheva, Prof. Dr. Darin Tenev, Georgi Ivanov, Silva Papazian, Alexander Krastev Design: Damyan Damyanov Proofreading and editing: Angela Rodel Project account: Ani Hristova Coordinator: Yanislava Yaneva © National Palace of Culture – Congress Centre Sofia 2015 2 Contemporary Bulgarian Writers 3 CONTENTS NATIONAL PALACE OF CULTURE Petar Delchev / 52 (NPC) / 11 CASTING CALL FOR A MESSIAH The National Book Center / 14 Theodora Dimova / 54 MOTHERS Elena Alexieva / 17 THE NOBEL LAUREATE Emiliya Dvoryanova / 59 AT THE DOORS OF THE SEA Kerana Angelova / 22 SUNFLOWERS FOR MARIA Deyan Enev / 64 CIRCUS BULGARIA Emil Andreev / 27 BOBBY THE BLESSED AND THE OTHER Zdravka Evtimova / 69 AMERICAN BLOOD OF A MOLE Georgi Bojinov / 32 Ludmila Filipova / 74 KALUNYA-KALYA THE WAR OF THE LETTERS Mona Choban / 37 Milena Fuchedjieva / 79 DOSTA SEX AND COMMUNISM Silvia Choleva / 42 Vasil Georgiev / 84 GREEN AND GOLD DEGRAD Lea Cohen / 47 Georgi Gospodinov / 87 THE COLLECTOR OF DIARIES THE PHYSICS OF SORROW 4 Contemporary Bulgarian Writers 5 Katerina Hapsali / 92 Diana Petrova / 154 Peter Tchouhov / 214 Virginia Zaharieva / 271 GREEK COFFEE SYNESTHESIA CAMOUFLAGE NINE RABBITS Angel Igov / 97 Alek Popov / 159 Georgi Tenev / 220 Vladimir Zarev / 276 A SHORT TALE OF SHAME THE BLACK BOX HOLY LIGHT RUIN Mirela Ivanova / 102 Palmi Ranchev / 165 Kalin Terziyski / 225 EMERGING WRITERS CLOSE AT HAND BOXERS AND PASSERS-BY ALCOHOL Aleksandar Chobanov / 285 Zachary Karabashliev / 107 Bogdan Rusev / 170 Vladislav Todorov / 230 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AIRPLANE THE ROOM ZINCOGRAPH Nadejda Dermendjieva / 286 Hristo Karastoyanov / 112 Milen Ruskov / 175 Ludmil Todorov / 235 Zornitsa Garkova / 287 THE SAME NIGHT AWAITS US ALL: SUMMIT A BARGE IN THE DESERT DIARY OF A NOVEL Aleksandar Hristov / 288 Alexander Sekulov / 179 Todor P. -

Hell Hath No Fury Like a Scorned Soap Fan

HELL HATH NO FURY LIKE A SCORNED SOAP FAN: A CASE STUDY OF SOAP OPERA FAN ACTIVISM A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Sarah Jane Adams In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Department: Communication May 2012 North Dakota State University Graduate School Title HELL HATH NO FURY LIKE A SCORNED SOAP FAN: A CASE STUDY IN SOAP OPERA FAN ACTIVISM By Sarah Jane Adams The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Ross F. Collins Chair Chair (signature) Dr. Carrie Anne Platt Dr. Mark Meister Dr. Christina Weber Approved by Department Chair: June 20, 2012 (Dr. Mark Meister / Department Chair) Date Signature ABSTRACT Soaps operas, or daytime serials, have long been a staple of American culture. In April 2011, ABC-Disney announced the cancellation of All My Children and One Life to Live. Cancellations propelled the fans of these programs to launch efforts to save not only the shows, but the genre. Through the use of social media, websites, and traditional off-line activities that included calling and letter-writing, fans strived to make their voices heard. The study examines the creation of an online community and discourse through a textual-analysis case study of blogs on two fan activist websites. Dahlberg’s criteria for presence in an online public space and Habermas’ public sphere allows for the presentation of ideas within a group to encourage a sense of democracy in a grassroots effort to be heard against corporate interests.