Muszynski, 2019-2020 1 HIGH RISE LIVING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Second Floor, City Hall

AGENDA OF MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC l[AY ON Tuesday, December B, 2015 Room 201-A Second Floor, City Hall 1:00 p m hJ kJ ë.Èl '" fY.i i - .' (J ¡,;l , It; ,." . i-i ,,: c.J i ' 'l.i í i r ";'¡ l -1,1 |\J f"At o ORDINANGES FOR GRANTS OF PRIVILEGE IN THE PUBLIC WAY: WARD (1) 1650-1654 W. DtVtStON, LLC . 02015-8111 To construct, install, maintain and use six (6) planter railings on the public right-of-way for beautification purposes adjacent to its premises known as 1664 West Division Street. (1) GHEES|E'S PUB & GRUB - 02015-8108 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1365 North Milwaukee Avenue. (1) NETGHBORSPACE - 02015-81 09 To maintain and use, as now constructed, one (1) lawn hydrant on the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1255 North Hermitage Avenue. (1) wHrsKEY BUSTNESS - 02015-8110 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1367 North Milwaukee Avenue. (2) AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION . 02015.8117 To maintain and use, as now constructed, two (2) vaults under the public righlof-way adjacent to its premises known as 211 East Chicago Avenue. (2) CHIGAGO TITLE LAND TRUST AS SUCGESSOR TRUSTEE UNDER TRUST NO, 34369 - 02015-8120 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1200 North State Parkway. -

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013 2013 Lake Baha’i Glenview 41 Wilmette Temple Central Old 14 45 Orchard Northwestern 294 Waukegan Golf Univ 58 Milwaukee Sheridan Golf Morton Mill Grove 32 C O N T E N T S Dempster Skokie Dempster Evanston Des Main 2 Getting Around Plaines Asbury Skokie Oakton Northwest Hwy 4 Near the Hotels 94 90 Ridge Crawford 6 Loop Walking Tour Allstate McCormick Touhy Arena Lincolnwood 41 Town Center Pratt Park Lincoln 14 Chinatown Ridge Loyola Devon Univ 16 Hyde Park Peterson 14 20 Lincoln Square Bryn Mawr Northeastern O’Hare 171 Illinois Univ Clark 22 Old Town International Foster 32 Airport North Park Univ Harwood Lawrence 32 Ashland 24 Pilsen Heights 20 32 41 Norridge Montrose 26 Printers Row Irving Park Bensenville 32 Lake Shore Dr 28 UIC and Taylor St Addison Western Forest Preserve 32 Wrigley Field 30 Wicker Park–Bucktown Cumberland Harlem Narragansett Central Cicero Oak Park Austin Laramie Belmont Elston Clybourn Grand 43 Broadway Diversey Pulaski 32 Other Places to Explore Franklin Grand Fullerton 3032 DePaul Park Milwaukee Univ Lincoln 36 Chicago Planning Armitage Park Zoo Timeline Kedzie 32 North 64 California 22 Maywood Grand 44 Conference Sponsors Lake 50 30 Park Division 3032 Water Elmhurst Halsted Tower Oak Chicago Damen Place 32 Park Navy Butterfield Lake 4 Pier 1st Madison United Center 6 290 56 Illinois 26 Roosevelt Medical Hines VA District 28 Soldier Medical Ogden Field Center Cicero 32 Cermak 24 Michigan McCormick 88 14 Berwyn Place 45 31st Central Park 32 Riverside Illinois Brookfield Archer 35th -

This Is Chicago

“You have the right to A global city. do things in Chicago. A world-class university. If you want to start The University of Chicago and its a business, a theater, namesake city are intrinsically linked. In the 1890s, the world’s fair brought millions a newspaper, you can of international visitors to the doorstep of find the space, the our brand new university. The landmark event celebrated diverse perspectives, backing, the audience.” curiosity, and innovation—values advanced Bernie Sahlins, AB’43, by UChicago ever since. co-founder of Today Chicago is a center of global The Second City cultures, worldwide organizations, international commerce, and fine arts. Like UChicago, it’s an intellectual destination, drawing top scholars, companies, entrepre- neurs, and artists who enhance the academic experience of our students. Chicago is our classroom, our gallery, and our home. Welcome to Chicago. Chicago is the sum of its many great parts: 77 community areas and more than 100 neighborhoods. Each block is made up CHicaGO of distinct personalities, local flavors, and vibrant cultures. Woven together by an MOSAIC OF extensive public transportation system, all of Chicago’s wonders are easily accessible PROMONTORY POINT NEIGHBORHOODS to UChicago students. LAKEFRONT HYDE PARK E JACKSON PARK MUSEUM CAMPUS N S BRONZEVILLE OAK STREET BEACH W WASHINGTON PARK WOODLAWN THEATRE DISTRICT MAGNIFICENT MILE CHINATOWN BRIDGEPORT LAKEVIEW LINCOLN PARK HISTORIC STOCKYARDS GREEK TOWN PILSEN WRIGLEYVILLE UKRAINIAN VILLAGE LOGAN SQUARE LITTLE VILLAGE MIDWAY AIRPORT O’HARE AIRPORT OAK PARK PICTURED Seven miles UChicago’s home on the South Where to Go UChicago Connections south of downtown Chicago, Side combines the best aspects n Bookstores: 57th Street, Powell’s, n Nearly 60 percent of Hyde Park features renowned architecture of a world-class city and a Seminary Co-op UChicago faculty and graduate alongside expansive vibrant college town. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

January 15Th, 2018

The Dearborn Express Sponsored by the South Loop Referral Group dearbornexpress.org Serving Printers Row and Dearborn Park Al Hippensteel, editor [email protected] Janice Koerber, Asst. Editor Jan. 15, 2018 Vol. 6, No. 1 Five Year Anniversary In this Issue This is our 83rd Issue. Beth Finke. Annelore Chapin, We started this publi- Beth’s guest writer, Takes “An cation on February 1, Optimistic look at the Future.” 2013. It was no acci- Page 9 dent. We heard that the local newspaper , the Chicago Jour- nal, was going to Bonnie McGrath. Two things that cease publication in really drive me crazy about the the South Loop. We new tax bill: bums and elitists decided that it would Page 4 be a worthwhile effort if we tried to, in some Mondays with Mike: Speaks to a small way, replace some of the news that was lost. We documentary about Daniel Ells- don’t pretend to be the Journal’s equal. They were a berg and the Pentagon Papers. professional publication with a paid staff. This is strictly a non-profit effort. Our goal is to support local Page 5 businesses and local organizations and provide news of Printers Row and Dearborn Park. It is sponsored by the South Loop Referral Group, a networking group Marianne Goss. of small business owners. We would like to thank Should safety experts study those who have contributed to providing quality, lively occasional drivers? reading. Page 18 Bonnie McGrath has been in every issue, Beth Finke joined us in September, 2013 with her wit and WOMEN’S MARCH JAN 20TH, SEE PG 15 wisdom. -

I. Introduction

I. Introduction A. The University Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) is an independent, non-sectarian, co-educational, and urban university emphasizing education for the professions, research, and scholarship. The university offers programs in engineering, science, architecture, law, business, psychology, and design, and is a member of the Association of Independent Technological Universities. With its contract research arm, IIT Research Institute (IITRI), IIT is a major center of applied science and engineering research. IIT has five campuses in the Chicago area: the Main Campus on Chicago’s mid-South Side; the Downtown Campus in Chicago’s West Loop; the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Campus in west suburban Wheaton; the Moffett Campus in south suburban Bedford Park, where the National Center for Food Safety and Technology is located; and the Institute of Design (ID) at 350 N. LaSalle St., in Chicago. In the 1950s, the university’s Main Campus was designed by master architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and has been designated one of the 200 most architecturally significant sites in the United States. The opening in 2003 of a new campus center designed by Rem Koolhaas and a dormitory by renowned architect Helmut Jahn has broadened and enhanced the architectural significance of the Main Campus. B. History In 1890, when advanced education was often reserved for society’s elite, Chicago minister Frank Gunsaulus delivered what came to be known as the “Million Dollar Sermon.” From the pulpit of his South Side church—near the site IIT now occupies—Gunsaulus said that with a million dollars he could build a school where students of all backgrounds could prepare for meaningful roles in a changing society. -

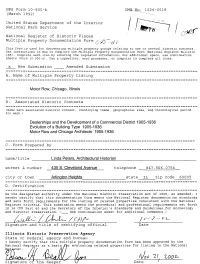

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Clc E-Brochure Tour Cruises

1-09 ★★★★★★ “Six of six stars, Architectural + by far the most comprehensive and engaging tour of the bunch.” Historical Cruises 2009 Time Out Chicago NORTH PIER DOCKS at RIVER EAST ART CENTER We invite you to learn more about Chicago’s past, present, and future at our Tour Partner’s newly redesigned Galleries at 1601 North Clark Street. www.chicagoline.com Purchase Tickets online at Purchase Tickets 2 Critics say that if you have only two hours in Chicago this is how to spend it: “WITHOUT QUESTION THE BEST ARCHITECTURAL TOUR AVAILABLE IN CHICAGO: WITTY, INFORMATIVE, ENGAGING.” CHICAGO SUN-TIMES www.chicagoline.com Click Here To Purchase Tickets 3 The thriving river cities of St. Louis and Cincinnati each had at least a 20-year head start on Chicago. Places such as Milwaukee and even Kenosha were more naturally blessed. But it was here – on a swampy and malodorous scrap of land so unpromising the Potawatomi had hardly bothered to settle it – where the American story took root and grew to epic proportions. Marquette and Jolliet once had been forced to laboriously portage their canoes over this dank, mucky expanse at the southern tip of Lake Michigan, called “wild garlic” by locals and later referred to derisively as Mud Lake. But in the early 1800’s that was no obstacle for the indomitable spirit of newly-arrived Easterners who would carve canals, tunnel under the lake itself, and later hoist the foundations of the entire City, four to seven feet, just to keep their feet dry. Mud Lake soon became the vital link to the Mississippi and the Great Lakes, the heartland and the Atlantic, the past and future – with Chicago in the center. -

Local Links for SAA Web Site

LOCAL LINKS FOR SAA ANNUAL MEETING WEB SITE Updated: April 30, 2007 Locations are Chicago, IL unless otherwise noted. Telephone number in right column indcates no web site. IN TWELVE SECTIONS 1. GENERAL AND LOGISTICS 7. MUSEUMS, ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES, PARKS, AND OTHER CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS 2. ARCHIVAL ORGANIZATIONS 8. MUSIC, THEATER, AND FILM 3. BOOKSTORES 9. ORGANIZED SIGHTSEEING AND TOURS 4. COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES 10. SPORTS AND RECREATION 5. DINING--PART 1--DINING GUIDES AND REVIEWS 11. TOURIST SITES AND HISTORIC AREAS AND NEIGHBORHOODS 6. DINING--PART 2--NEARBY RESTAURANTS (SEE MAP) 12. TRANSPORTATION 1. GENERAL AND LOGISTICS Chicago and Illinois Tourist Office http://www.gochicago.com/ Chicago Convention and Tourism Bureau http://www.choosechicago.com/ Chicago Defender (newspaper) http://chicagodefender.com/ Chicago Greeter (volunteer city orientation service) http://chicagogreeter.com/ Chicago Magazine (monthly magazine) http://chicagomag.com/ Chicago Quick Guide http://guestinformant.com Chicago Reader (alternative weekly newspaper) http://chicagoreader.com Chicago Sun-Times (newspaper) http://www.suntimes.com Chicago Traveler http://www.chicagotraveler.com/ Chicago Tribune (newspaper) http://chicagotribune.com City of Chicago (city government) http://www.cityofchicago.org City Pass (multi-attraction pass) http://www.citypass.com Cook County (county government) http://www.co.cook.il.us Enjoy Illinois (Illinois tourism information) http://www.enjoyillinois.com/ Fairmont Chicago Hotel http://www.fairmont.com/chicago/ Fodor's Guide -

High Rise Agreement by and Between Apartment

FOR ABOMA MEMBER USE ONLY Apartment Building Owners and Managers Association of Illinois HIGH RISE AGREEMENT BY AND BETWEEN APARTMENT BUILDING OWNERS AND MANAGERS ASSOCIATION OF ILLINOIS and SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION LOCAL 1 Residential Division for the period DECEMBER 1, 2014 THROUGH NOVEMBER 30, 2017 Covering Head Janitors and Other Employees as specified in Article II, Section 1(g) who are employed in ABOMA Member High Rise (Fireproof) Buildings who have authorized ABOMA to include them in this agreement. ABOMA Presidential Towers 625 West Madison Street Suite 1403 Chicago, Illinois 60661 Phone: (312) 902-2266 FAX: (312) 284-4577 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: aboma.com Apartment Building Owners and Managers Association of Illinois ABOMA SEIU LOCAL 1 JANITORIAL COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT OVERVIEW OF CHANGES EFFECTIVE DECEMBER 1, 2014 JANITORIAL EMPLOYEES—HIGH RISE BUILDINGS Pages I through III is an Overview of the changes in the terms, wages and benefits which become effective December 1, 2014 in the High Rise Agreement by and between ABOMA and Building Services Division of SEIU Local 1 for the period beginning December 1, 2014 through November 30, 2017 Covering Head Janitors and Other Employees as specified in Article II, Section 1(g) who are employed in ABOMA Member High Rise (Fireproof) Buildings who have authorized ABOMA to include them in this agreement. Please reference the full CBA to fully understand the language changes highlighted in the Overview-pages I through III This agreement does not cover non-member buildings or Member Buildings who have not authorized ABOMA to include them in the negotiations or the resulting contract.