Pakistan Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for University Honors with Distinction by, Brandon Smith May 2005 Oxford, OH ABSTRACT AFGHANISTAN, 1989-1996: BETWEEN THE SOVIETS AND THE TALIBAN by, BRANDON SMITH This paper examines why the Afghan resistance fighters from the war against the Soviets, the mujahideen, were unable to establish a government in the time period between the withdrawal of the Soviet army from Afghanistan in 1989 and the consolidation of power by the Taliban in 1996. A number of conflicting explanations exist regarding Afghanistan’s instability during this time period. This paper argues that the developments in Afghanistan from 1989 to 1996 can be linked to the influence of actors outside Afghanistan, but not to the extent that the choices and actions of individual actors can be overlooked or ignored. Further, the choices and actions of individual actors need not be explained in terms of ancient animosities or historic tendencies, but rather were calculated moves to secure power. In support of this argument, international, national, and individual level factors are examined. ii Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban by, Brandon Smith Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Karen L. Dawisha _________________________, Reader John M. Rothgeb, Jr. _________________________, Reader Homayun Sidky Accepted by: ________________________, Director, University Honors Program iii Thanks to Karen Dawisha for her guidance and willingness to help on her year off, and to John Rothgeb and Homayun Sidky for taking the time to read the final draft and offer their feedback. -

Remembering Nancy Hatch Dupree 2: Nancy in the Words of Others

Remembering Nancy Hatch Dupree 2: Nancy in the words of others Author : AAN Team Published: 21 October 2017 Downloaded: 5 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/remembering-nancy-hatch-dupree-2-nancy-in-the-words-of-others/?format=pdf It is 40 days since the historian, archivist and activist on behalf of Afghans, Nancy Hatch Dupree, died, aged 89. She had spent decades of her life in Afghanistan or, like many Afghans, in exile in neighbouring Pakistan. She was the author of guidebooks on Afghanistan and a publisher of books. Then, first with her husband, Louis, and, after he died in 1989, by herself, Nancy amassed the most extensive archive of documents of the last forty years. Those 100,000 documents are now housed in a special building, known as the Afghanistan Collection at Kabul University (ACKU). Last night, in London, friends and colleagues met to celebrate Nancy’s life and mark her passing. Here, we publish some of the tributes that were made that evening. 1 / 12 Our first despatch to mark Nancy’s ‘fortieth day’, a republishing of an interview she gave in 2007, can be read here. See also AAN’s obituary for her and our report about the opening of the AFKU here. Shoaib Sharifi, journalist My first exposure to the name ‘Nancy Dupree’ goes back 18 years to 1998 when I joined Voice of Sharia, the official name of Radio Afghanistan under the Taliban. At a time when the world thought of Afghanistan as in one of its darkest eras and against all odds, as a newly recruited intern, I was assigned to introduce Afghanistan, its art and culture to the world via Radio Voice of Sharia’s English Programme. -

Afghan Refugees Camp Population in KP March, 2018

SOLUTION STRATEGY UNIT COMMISSIONERATE AFGHAN REFUGEES KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PESHAWAR March, 2018 CAMP WISE AFGHAN REFUGEES POLULATION IN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA S/No Name of District Name of Admn Camp Cluster Camps Population FAM IND 1 Kababian 2,3 764 4194 Kababian Michani/Warsak 30 196 2 Badaber 2840 14438 3 Khazana Khazana / Wahid Gari 921 4434 4 Naguman 410 2437 5 Khurasan 376 2259 Mere Kachori, Zandai 541 3400 6 Peshawar Mera Kachori Baghbanan 2149 9770 7 Shamshatoo Gul Badin, Old/ Molvi Khalid 3631 18817 Sub-Total Peshawar 11662 59945 8 Utmanzai 535 3268 Munda - I-II 1007 5099 9 Munda Ekka Gund 363 1471 10 Hajizai 501 2880 Sub-total Charsadda 2406 12718 Charsadda Akora Khattak Akora new, Hawai, 4509 22606 11 Kheshki 210 1710 12 Khairabad Khairabad 1926 9239 13 Turkaman Turkaman/Jalozai 410 2820 Nowshera Sub-Total Nowshera 7055 36375 14 Lakhti Banda 294 2085 Kata Kani 1000 6007 15 Kata Kani Kotki 297 2054 Kahi-I-II 1020 7937 16 Kahi Doaba 46 1165 17 Darsamand I-II 1640 10916 Hangu 18 Thall Thall-I-II 1270 12035 Sub-Total Hangu 5567 42199 19 Gamkol Gamkol -I-II-III 4932 30713 Oblen 1338 8081 20 Oblen Jarma 375 1067 Ghulam Banda 1021 6208 21 Ghulam Banda Shin Dhand 236 1426 22 Chichana 611 3901 Sub-Total Kohat 8513 51396 23 Jalala Jalala 1,2,3 1496 8187 Baghicha 481 2743 24 Baghicha Kagan 249 1352 Mardan Sub-Total Mardan 2226 12282 25 Barakai 2013 12606 Barakai Fazal 810 2731 26 Gandaf 2823 18226 Swabi Sub-Total Swabi 5646 33563 27 Zangal Patai 696 4125 Sub-Total Malakand 696 4125 Malakand Kohat Koga 1680 7972 28 Buner Sub-Total Buner 1680 -

The Emergency Shelter Process with Application to Case Studies in Macedonia and Afghanistan

1 The Emergency Shelter Process with Application to Case Studies in Macedonia and Afghanistan by Elizabeth Babister and Ilan Kelman www.shelterproject.org [email protected] [email protected] Research completed at: The Martin Centre University of Cambridge 6 Chaucer Road Cambridge, England CB2 2EB U.K. January 2002 2 Contents All sources are provided in footnotes. 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................2 2. Methodology.................................................................................................................................3 3. Shelter as a Fundamental Human Need: The State of the Art ......................................................4 3.1 The Implied Right to Shelter ..................................................................................................4 3.2 The Fundamental Need for Shelter.........................................................................................4 3.4 How Those in Need are Recognised by the Implementers of Relief......................................8 3.5 Emergency Shelter Responses Experienced by Forced Migrants ........................................10 3.6 Conclusions to Shelter as a Fundamental Human Need.......................................................13 4. The Emergency Shelter Process .................................................................................................15 4.1 The Emergency Shelter Sector .............................................................................................18 -

Evaluation of the UNHCR Shelter Assistance Programme in Afghanistan

Evalua on of the UNHCR Shelter Assistance Programme Final Dra The Maastricht Graduate School of Governance (MGSOG) is the Public Policy Graduate School of Maastricht University, combining high-level teaching and research. The institute provides multi-disciplinary top-academic training. Doing so, it builds on the academic resources of the different faculties at Maastricht University as well as those of several foreign partners. In January 2011, the School became part of the United Nations University, strengthening further its international training and research network while building on the expertise of UNU-MERIT the Maastricht based research institute of the UNU. One of the key areas of education and research is Migration Studies, where MGSOG has gained a strong reputation. Samuel Hall. (www.samuelhall.org) is a research and consulting company with headquarters in Kabul, Afghanistan. We specialise in socio-economic surveys, private and public sector studies, monitoring and evaluation and impact assessments for governmental, non-governmental and international organisations. Our teams of field practitioners, academic experts and local interviewers have years of experience leading research in Afghanistan. We use our expertise to balance needs of beneficiaries with the requirements of development actors. This has enabled us to acquire a firm grasp of the political and socio-cultural context in the country; design data collection methods and statistical analyses for monitoring, evaluating, and planning sustainable programmes and to apply cross- disciplinary knowledge in providing integrated solutions for efficient and effective interventions. Acknowledgements The research team would like to thank, first and foremost, the men, women, children who agreed to participate in this research and share their experiences throughout the 15 provinces surveyed. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Province-Wise Quarantine Facilities Sr Locations

LIST OF PROVINCE-WISE QUARANTINE FACILITIES SR LOCATIONS BEDS Islamabad 1. Hajji Camp 300 2. Pak-China Friendship Centre 50 Total 350 Balochistan 1. Turkish Colony, District Jaffarabad 50 2. Midwifery School, District Naseerabad 50 3. DHQ Hospital Kachi 50 4. Boys Highschool Gandawah, District Jhal Magsi 50 5. Boys Highschool Digri, District Sohbatpur 50 6. Sheikh Khalif Bin Zayed Hospital, District Quetta 56 7. Gynae & General Private Hospital, District Quetta 24 8. Customs House Taftan 17 9. Taftan Quarantine 4,950 10. PCSIR Laboratory Compound 600 Total 5,897 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 1. Landi Kotal, District Khyber 102 2. Darazinda, District Dera Ismail Khan 200 3. Peshawar 500 4. Gomal Medical College, District Dera Ismail Khan 200 5. RHC Dassu, District Kohistan 2 6. RHC Shetyal, District Kohistan 2 7. GHSS Boys, District Mohmand 20 8. GHS Ekkaghund, District Mohmand 30 9. Hostel Bahai Daag AC Complex, District Mohmand 20 10. DHQ Hospital Nursing Hostel, District Bajaur 30 11. Type D Hospital Nawagai, District Bajaur 30 12. Type D Hospital Larkhalozo, District Bajaur 60 13. Post Graduate College, District Bajaur 50 14. Degree College Nawagai, District Bajaur 50 15. Degree College Barkhalozo, District Bajaur 50 16. Bachelor Hostel Daag Qilla, District Bajaur 20 17. BHU Dehrakai, District Bajaur 10 18. RHC Arang, District Bajaur 10 19. GHS Khar No-2, District Bajaur 20 20. Govt. Degree College Wari, District Dir Upper 55 21. Govt. Degree College, District Dir Upper 35 22. Govt. Technical College, District Nowshera 50 23. Govt. Post Graduate College, District Nowshera 100 24. GHSS Khairabad, District Nowshera 20 25. -

PIPOS Peshawar

Khyber Medical University, Peshawar List of Students (Govt Instts Only) Securing 60 % or Above Marks in all Semester Exam of BSc Prothetics & Orthotic Sciences (Last held) S.NO Sr. No Name of College Student's Name Father's Name Contact No. Residence Address CNIC No. Roll No. Marks Obtained %age Date of Declaration of Result 3rd Semester Final Result 1 1 Amna Akhtar Akhtar Ali 3475847887 Saeed Abad No.1 Dalazak road, H No. E/786 Street No. 1 17301-1456199-6 313 580/800 72% 2 2 Hafiz M Israr Ghulam Muhammad 3339212299 Tehsil /P.O Mir Ali North Waziristan Agency 21505-8424576-9 314 543/800 67% 3 3 Sania Hadi Abdul Hadi 32181834961 H# 238, street#11, sector K2, Phase 3 Hayatabad 54401-0629812-6 315 602/800 75% 4 4 Qurat-ul-Ain Rehamt Ullah Khan 3338929400 Near Sardar floor Mills H. No. 1508/134 Muhallah Chahpipal DIK 12101-6609333-0 317 560/800 70% 5 5 Omer Ashfaq Ashfaq Ahmad 3323176536 A-201 afnan Arcade Gulistan-e-Jauhar BIK-15 Karachi 42201-6716438-5 318 568/800 71% 6 6 Pakistan Institute Benazir Kakar Bismillah Khan Kakar 3337847542 H# 238, street#11, sector K2, Phase 3 Hayatabad 54203-9522698-0 319 628/800 79% 7 7 of Prosthetic and Nasir Khan Maqool Ahmad 3469401540 Durushkhela (Bala) Teh: Matta Distt: Swat 15601-4772319-7 320 552/800 69% Dated: 20-07-2012 8 8 Orthetic Sciences Zara Muzaffar Khan Dr. Muzaffar Khan 3337915089 House#238 street No. 11, Sector K2, Phase 3, Hayatabad Peshawar 54400-2565876-0 321 601/800 75% 9 9 Asif Niaz Rasool Dayaz 3339291172 Tehsil Mir Ali village and P.O Eidak North Waziristan Agency 21505-5662717-3 322 556/800 70% 10 10 Syeda Zillay Huma Syed Shafiq Ahmad 3418847463 Frontier Homeopathic Medical College Near RMC hayatabad 82101-3425905-8 323 595/800 74% 11 11 Usama Muhammad Muhammad Anwar 3219773974 Moh: Shiekan Village Khudrizi PO pabbi Distt Nowshera 17201-1189715-1 324 585/800 73% 12 12 Aqsa Khan Muhammad Saleem Khan3326976755 Moh: Bhoora Shah, DIK 12101-5356336-8 325 607/800 76% 13 13 Aizaz Ali Shah Zahir Shah 3139785351 House#424 street No. -

National Talent Scholarship SSC Annual Exam 2015

- #&, -" $oarf of Intermefrate pesfrawar @ st Secon[ory lEtucation SSC NOTIFICATION 2015 It is hereby notified that the following top twenty five (25) position holders i.e science Group-I7 and HumanitievArts Group-8 have been declared entitled/eligible for Peshawar Board National ralent scholarship on the basis of secondary schoot certificate (Annual) Examination 2015 result. CE Roll S.No. Pos: Marks/ Name F/llame School No. Grade Name Address/Contact No. Dr Waheed I I l 43858 Fuaz Watreed 1040-Al Fonvard Model School HA'{o.143, Street No.3, K-4, Khan Hayatabad Peshawar Hayatabad, Peshawar. 091-58 16395 Muhammad t44049 Shehzada Frontier Childern Academy Jinnah Hostel, Shaheen Town, Saeed Afridi 1037-4l ? ? Hayatabad Peshawar Peshawar. 0303 -8420082 3 3 I 4405 I Intikhab Alam Islam Shah 1035-Al Frontier Childern Academy HA'{o. 129, Street-6, N- 1, phase-IV, Hayatabad Peshawar Hayatabad, Peshawar. 0305-90 16362 Araish Hoor 4 4 106579 Rooh Ullatr 1034-4l New Islamia Public High Mohalla Quaidabad, Charsadda. Shehzadi School Charsadda 0301-9933750 Umair Ali Mohalla Labikhel, Village, Janakor, 5 5 t43267 Sardar Afridi Ali 1032-4l University Public School F.R, Peshawar. 091-561I156, 0345- Peshawar 9046553 House No.6l4 Sector E-6, Phase-7, 6 6 t04072 Saffa Rashid Abdur Rashid l03l-Al Peshawar Model Girls High Hayatabad, Peshawar. 09 l -58633 14, School Warsak Road Peshawar 0332-99487s2 Zarrneena Muhammad 7 6 I 06593 New Islamia Public High Mohalla Tariqabad, Utm anzai, Ajmal l03l-Al Ajmal Khan School Charsadda Charsadda. 03 4 6-907 5996 Noor Abdur Rauf Islamia Collegiate School P/o Khujari Babar, Tehsil Kakki, 8 6 t42739 Muhammad (Main Khan l03l-Al Building, E/M) Distt: Bannu. -

Aid Workers Or Evangelists, Charity Or Conspiracy: Framing of Missionary Activity As a Function of International Political Alliances

Messiah University Mosaic Communication Educator Scholarship Communication 1-1-2005 Aid Workers or Evangelists, Charity or Conspiracy: Framing of Missionary Activity as a Function of International Political Alliances David N. Dixon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/com_ed Part of the Communication Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/com_ed/2 Recommended Citation Dixon, David N., "Aid Workers or Evangelists, Charity or Conspiracy: Framing of Missionary Activity as a Function of International Political Alliances" (2005). Communication Educator Scholarship. 2. https://mosaic.messiah.edu/com_ed/2 Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service, leadership and reconciliation in church and society. www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055 Aid Workers or Evangelists, Charity or Conspiracy: Framing of Missionary Activity as a Function of International Political Alliances David N. Dixon Department of Communication Arts Malone College In 2001, Christian aid workers were arrested by the Taliban in Afghanistan on charges of proselytizing. A year later, Baptist hospital workers were gunned down in Yemen. In one case, the country was an enemy of the United States; in the other, the country was an ally. The way in which the proselytizing and the national government was portrayed changed from one set of news coverage to the other, suggesting that political interests, not religious ones, drive this coverage. -

Evangelicals Influence on Us Foreign Policy: Impact on Pak-Us Relations (September 2001 – November 2007)

EVANGELICALS INFLUENCE ON US FOREIGN POLICY: IMPACT ON PAK-US RELATIONS (SEPTEMBER 2001 – NOVEMBER 2007) MINHAS MAJEED KHAN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR JANUARY 2013 i Source: United States Information Agency ii Source: www.worldatlas.com iii GLOSSARY American Exceptionalism: It refers to the theory that the United States is qualitatively different from other nations with a special role based on liberty, egalitarianism, populism and laissez faire, to lead the world. Baptism: It means ‘to dip in water’. Baptism, by full immersion, was the ritual of admission to the early Christian community. Born Again: It refers to a Christian who has made a renewed or confirmed commitment of faith especially after an intense religious experience. Congregationalism: A Christian movement starting in the late sixteenth century in England that emphasized on the independence and autonomy of each local church congregation, and as such it eliminated bishops and presbyteries. Congregationalists were called independents, who were persecuted by the established Church due to which they fled to Holland, others to America with the Mayflower in 1620. Dispensationalism: It is also known as ‘Dispensational Pre-Millennialism’ which maintained that history is divided into distinct periods or dispensations and that God dealt differently with humanity in each of these periods. Furthermore, it insists that humanity is now moving towards the end of the final dispensation and that Jesus would return at any moment.It became popular among Evangelicals in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Dominionism: Dominionists take their desire for a theocratic state to its logical conclusion and seek Christian dominion over not just America but the world. -

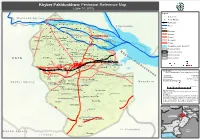

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa- Peshawar Reference Map (June 14, 2012)

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa- Peshawar Reference Map (June 14, 2012) Legend ! ! ! Settlements M o h m a n d A g e n c y ! ! ! ! ! ! "' Health Facilities WAZIRBAGH Railway Line ! ! ! ! "' ! SHA!GI BAL!A(KHAT!KI) ! ! ! Jogani "' Rivers ! C h a r s a d d a ! C h a r s a d d a ! ! ! ! ! ! Kha! tki ! ! Roads SAEED ABAD ! CHAGHAR MATTI "' FAQIR KILLAYGARA TAJIK"' Motorway ! ! "'! ! "' ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Highway HUSSAIN ABAD Gul Bela GUL BELLA ! "' TAKHT ABAD "' "' ! !Gar!hi S! her D!ad ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! NASIR BAGH "' "' Primary KAFOOR DHERI Chaghar "'Matti ! "' MATHRA NAHAQI ! "' MATHRA "' KHARAKI Secondary ! Pana!m Dhe!ri ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "' ! ! ! "' CHARPERIZATakhat Abad ! "' Tertiary SUFAID DHERI PUTWAR BALLA KHAZANA ! "' ! ! "'! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "' Flood Extenct (Oct -Nov 2010) ! ! Nahaqi ! Kaniza Ka!foor D!heri ! ! ! ! ! ! MA! NDRA !KHEL ! ! ! ! ! Peshawar District ! "' DARMANGI K Provincial boundary ! ! ! ! "' ! ! ! Khaza! na ! ! ! ! h "' Haryana Payan ! Mathra PAKHA GHULAM WADPAGA y District boundary ! TARAI PAYAN(SHAQI H.K) "' Kankola "' b ! ! Shahi Bala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e Union Councils PALOSA!IUrban BUDH!AI F A T A "' ! ! "'! r ! Budhni Palosi Pajjagi ! ! P ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "' JO!GANI ! JHAGRA a Dag CHAMKAN"'I "' "' ! k REGAI PESHAWAR Laram "'BAZAR KALAN TARNAB FARM k "' "' ! Pakha Ghulam "' RASHID ABAD (NCB) h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! t ISLAMIA COLLEGE HOSPITAL, PESHAWZANANA HOSPITAL, PESHAWAR Wad Paga t ! PHANDOO PAYAN u "' "' "' Regi Palosi Lala n ! Urban Ar! ! ! LANDI ARBAB k Map Doc Name: "' h iMMAP_Peshawar District Reference