Situationist International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home-Stewart Plagiarism.-Art-As-Commodity-And-Strategies-For-Its-Negation.Pdf

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Plagiarism: art as commodity and strategies for its negation 1. Imitation in art — History — 20th century 2. Art — Reproduction — History — 20th century I. Home, Stewart 702.8'7 N7428 ISBN 0-948518-87-1 Second impression Aporia Press, 1987. No copyright: please copy & distribute freely. INTRODUCTION THIS is a pamphlet intended to accompany the debate that surrounds "The Festival Of Plagiarism", but it may also be read and used separately from any specific event. It should not be viewed as a cat alogue for the festival, as it contains opinions that bear no relation to those of a number of people participating in the event. Presented here are a number of divergent views on the subjects of plagiarism, art and culture. One of the problems inherent in left opposition to dominant culture is that there is no agreement on the use of specific terms. Thus while some of the 'essays' contained here are antagonistic towards the concept of art — defined in terms of the culture of the ruling elite — others use the term in a less specific sense and are consequently less critical of it. Since the term 'art' is popularly associated with cults of 'genius' it would seem expedient to stick to the term 'culture' — in a non-elitist sense — when describing our own endeavours. Although culture as a category appears to be a 'universal' experience, none of its individual expressions meet such a criteria. This is the basis of our principle objection to art — it claims to be 'universal' when it is very clearly class based. -

The Healthcare Riskops Manifesto

The Healthcare RiskOps Manifesto “Committees are, by nature, timid. They are based on the premise of safety in numbers; content to survive inconspicuously, rather than take risks and move independently ahead. Without independence, without the freedom for new ideas to be tried, to fail, and to ultimately succeed, the world will not move ahead, but rather live in fear of its own potential” Ferdinand Porsche And you may ask yourself, "How do I work this?" And you may ask yourself, "Where is that large automobile?" And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful house." And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful wife." David Byrne The End is Near “People of Earth, hear this!” A specter is haunting healthcare. And we’ve got work to do. It’s about challenging the old assumptions of managing risk because nothing has changed. Yet, everything has changed. It’s about heralding a new vision because the old one doesn’t work. Change creates opportunities. Change drives outcomes. And healthcare needs secure outcomes. Healthcare risk needs change. We must challenge assumptions: identity, role, purpose, place, power. Change built on strong beliefs that will upset the status quo. We don’t care. We are focused on moving the industry forward. Le risque est avant-gardiste. Futurism. Vorticism. Dada. Surrealism. Situationism. Neoism. Risk the Elephant. Uncaged. Risk is Nazaré. It’s a red balloon. Risk is sunflower fields. And fire on the mountain. Risk guides the first decision. It’s as old as Eden. Fight. Or flight. Risk is nucleotide. To ego. -

00A Inside Cover CC

Access Provided by University of Manchester at 08/14/11 9:17PM GMT 05 Thoburn_CC #78 7/15/2011 10:59 Page 119 TO CONQUER THE ANONYMOUS AUTHORSHIP AND MYTH IN THE WU MING FOUNDATION Nicholas Thoburn It is said that Mao never forgave Khrushchev for his 1956 “Secret Speech” on the crimes of the Stalin era (Li, 115–16). Of the aspects of the speech that were damaging to Mao, the most troubling was no doubt Khrushchev’s attack on the “cult of personality” (7), not only in Stalin’s example, but in principle, as a “perversion” of Marxism. As Alain Badiou has remarked, the cult of personality was something of an “invariant feature of communist states and parties,” one that was brought to a point of “paroxysm” in China’s Cultural Revolution (505). It should hence not surprise us that Mao responded in 1958 with a defense of the axiom as properly communist. In delineating “correct” and “incorrect” kinds of personality cult, Mao insisted: “The ques- tion at issue is not whether or not there should be a cult of the indi- vidual, but rather whether or not the individual concerned represents the truth. If he does, then he should be revered” (99–100). Not unex- pectedly, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and “the correct side of Stalin” are Mao’s given examples of leaders that should be “revere[d] for ever” (38). Marx himself, however, was somewhat hostile to such practice, a point Khrushchev sought to stress in quoting from Marx’s November 1877 letter to Wilhelm Blos: “From my antipathy to any cult of the individ - ual, I never made public during the existence of the International the numerous addresses from various countries which recognized my merits and which annoyed me. -

MACBA Coll Artworks English RZ.Indd

of these posters carry the titles of Georges Perec’s novels, but Ignasi Aballí very few were actually made into Flms. We might, however, Desapariciones II (1 of 24), 2005 seem to remember some of these as Flms, or perhaps simply imagine we remember them. A cinema poster, aker it has accomplished its function of announcing a Flm, is all that’s lek of the Flm: an objective, material trace of its existence. Yet it also holds a subjective trace. It carries something of our own personal history, of our involvement with the cinema, making us remember certain aspects of Flms, maybe even their storylines. As we look at these posters we begin to create our own storylines, the images, text and design suggesting di©erent possibilities to us. By fabricating a tangible trace of Flms that were never made, Desaparicions II brings the Flms into existence and it is the viewer who begins to create, even remember these movies. The images that appear in the posters have all been taken from artworks made by Aballí. As the artist has commented: ‘In the case of Perec, I carried out a process of investigation to construct a Fction that enabled me to relate my work to his and generate a hybrid, which is something directly constructed by me, though it includes real elements I found during the documentation stage.’ 3 Absence, is not only evident in the novel La Disparition, but is also persistent in the work Aballí; mirrors obliterated with Tipp-Ex, photographs of the trace paintings have lek once they have been taken down. -

The Game of War, MW-Spring 2008

The Game of War: Debord as Strategist By McKenzie Wark for Issue 29 Sloth Spring 2008 The only member of the Situationist International to remain at its dissolution in 1972 was Guy Debord (1931–1994). He is often held to be synonymous with the movement, but anti- Debordist accounts rightly stress the role of others, such as Asger Jorn (1914–1973) or Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005) who both left the movement as it headed out of its “aesthetic” phase towards its ostensibly more “political” one. Take, for example, Constant’s extraordinary New Babylon project, which he began while a member of the Situationist International and continued independently after separating from it. Constant imagined an entirely new landscape for the earth, one devoted entirely to play. But New Babylon is a landscape that began from the premise that the transition to this new landscape is a secondary problem. Play is one of the key categories of Situationist thought and practice, but would it really be possible to bring this new landscape for play into being entirely by means of play itself? This is the locus where the work of Constant and Debord might be brought back into some kind of relation to each other, despite their personal and organizational estrangement in 1960. Constant offered the kinds of landscape that the Situationists experiments might conceivably bring about. It was Debord who proposed an architecture for investigating the strategic potential escaping from the existing landscape of overdeveloped or spectacular society. Between the two possibilities lies the situation. Debord is best known as the author of The Society of the Spectacle (1967), but in many ways it is not quite a representative text. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

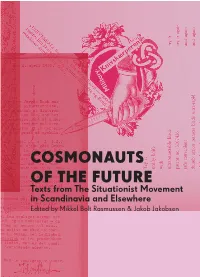

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263. -

Constant Nieuwenhuys-August 13, 2005

Constant Nieuwenhuys Published in Times London, August 13 2005 A militant founder of the Cobra group of avant-garde artists whose early nihilism mellowed into Utopian fantasy Soon after the war ended, the Cobra group burst upon European art with anarchic force. The movement’s venomous name was an acronym from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, the cities where its principal members lived. And by the time Cobra’s existence was formally announced in Paris in 1948, the young Dutch artist Constant had become one of its most militant protagonists. Constant did not hesitate to voice the most extreme beliefs. Haunted by the war and its bleak aftermath, he declared in a 1948 interview that “our culture has already died. The façades left standing could be blown away tomorrow by an atom bomb but, even failing that, still nothing can disguise the fact. We have lost everything that provided us with security and are left bereft of all belief. Save this: that we live and that it is part of the essence of life to manifest itself.” The Cobra artists soon demonstrated their own exuberant, heretical vitality. Inspired by the uninhibited power of so-called primitive art, as well as the images produced by children and the insane, they planned an idealistic future where Marxist ideas would form a vibrant union with the creation of a new folk art. Constant, born Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys, discovered his first motivation in a crucial 1946 meeting with the Danish artist Asger Jorn at the Galerie Pierre, Paris. They exchanged ideas and Constant became the driving force in establishing Cobra. -

How Language Looks: on Asger Jorn and Noël Arnaud's La Langue Verte*

How Language Looks: On Asger Jorn and No ël Arnaud’s La Langue verte* STEVEN HARRIS In November 1968, the Paris publisher Jean-Jacques Pauvert brought out Asger Jorn and Noël Arnaud’s La Langue verte et la cuite , an event accompanied by a banquet for 2,000 at a Danish restaurant in Paris, and a considerable response from the press, though the book has largely dropped from view since. 1 Initially titled La Langue crue et la cuite , the book was written in French by artist Asger Jorn, founding member of Cobra and of the Situationist International, and revised by Arnaud, member of the Surrealist “Main à plume” group in occupied Paris, founding member of the Revolutionary Surrealist group in postwar Paris (with which Jorn was also involved), and later regent in the Collège de ’Pataphysique. 2 Jorn, in addition to writing the text, also chose the illustrations, while Arnaud added sections of his own and reordered the material in collaboration with Jorn. It is thus the collective labor of two individuals who had first met in Paris in 1946, and who were both involved in the Revolutionary Surrealist group, a splinter group of Communist persuasion that had seceded from the main body of the Surrealist group shortly before the opening of its exhibition Le Surréalisme en 1947 , at the Galerie Maeght. If Cobra was very much ori - ented against Arnaud when it was first formed in 1948, the paths of the two men crossed numerous times in subsequent years. Jorn turned to Arnaud as a trusted friend who was in in sympathy with his aims, who corrected Jorn’s rather casual French, and who in general was willing to lend a hand to the enterprise. -

Agregue Y Devuelva, MAIL ART En Las Colección Del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM

AGREGUE Y DEVUELVA MAIL ART en las colecciones del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM © de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores. © de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Textos de: José Emilio Antón, Ibírico, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Sylvia Ramírez Monroy, César Reglero y Pere Sousa. Edita: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, MIDE-CIANT y Fundación Antonio Pérez. Colección CALEIDOSCOPIO n.º 17. Serie Cuadernos del Media Art. Dir.: Ana Navarrete Tudela Equipo de documentación: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Roberto J. Alcalde López y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez. Fotografías: Montserrat de Pablo Moya Corrección de textos: Antonio Fernández Vicente I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-421-4 (Edición impresa) I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-422-1 (Edición electrónica) Doi: http://doi.org/10.18239/caleidos_2021.17.00 D.L.: CU 11-2021 Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel nacional e internacional. Diseño y maquetación: CIDI (UCLM) Impresión: Trisorgar Artes Gráficas Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.) Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la autorización expresa de los titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al texto completo de la licencia en este enlace: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es EXPOSICIONES: Comisariado: Patricia Aragón Martín, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Montserrat de Pablo Moya Coordinación: Ana Navarrete Tudela Ayudantes de coordinación: Adoración Saiz Cañas, Ana Alarcón Vieco, Ignacio Page Valero Dirección de montaje: MIDE-CIANT/UCLM, Fundación Antonio Pérez, ArteTinta Digitalización: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Patricia Aragón y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez Montaje y transporte: ArteTinta Centros: Sala ACUA, Cuenca. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, Edited by Tom Mcdonough G D S I

G D S I OCTOBER BOOKS Rosalind E. Krauss, Annette Michelson, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Mignon Nixon, editors Broodthaers, edited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, edited by Douglas Crimp Aberrations, by Jurgis Baltrusˇaitis Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, by Denis Hollier Painting as Model, by Yve-Alain Bois The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, edited by Clara Weyergraf-Serra and Martha Buskirk The Woman in Question, edited by Parveen Adams and Elizabeth Cowie Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, by Jonathan Crary The Subjectivity Effect in Western Literary Tradition: Essays toward the Release of Shakespeare’s Will, by Joel Fineman Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, by Slavoj Zˇizˇek Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, by Nagisa Oshima The Optical Unconscious, by Rosalind E. Krauss Gesture and Speech, by André Leroi-Gourhan Compulsive Beauty, by Hal Foster Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, by Robert Morris Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists, by Joan Copjec Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture, by Kristin Ross Kant after Duchamp, by Thierry de Duve The Duchamp Effect, edited by Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, by Hal Foster October: The Second Decade, 1986–1996, edited by Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Silvia Kolbowski Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910–1941, by David Joselit Caravaggio’s Secrets, by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843–1875, by Carol Armstrong Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, by Benjamin H.