Onshore Oil and Gas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

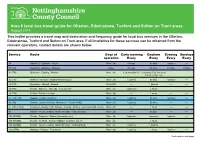

Area 6 Local Bus Travel Guide for Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford And

Area 6 local bus travel guide for Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford and Sutton on Trent areas August 2014 This leaflet provides a travel map and destination and frequency guide for local bus services in the Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford and Sutton on Trent area. Full timetables for these services can be obtained from the relevant operators, contact details are shown below. Service Route Days of Early morning Daytime Evening Sundays operation Every Every Every Every 14 Mansfield - Clipstone - Kirton Mon - Sat 60 mins 60 mins 1 journey ---- 15, 15A Mansfield - Clipstone - Walesby Daily 60 mins 60 mins 60 mins 60 mins 31 (TW) Bilsthorpe - Eakring - Ollerton Mon - Sat 1 journey (Mon-Fri) 3 journeys (Tue, Thur & Sat) ---- ---- 1 journey (Mon - Sat) 32 (TW) Ollerton - Kneesall - Newark (Phone a bus*) Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins 1 journey ---- 33 (TW) Egmanton - Norwell - Newark Wed & Fri ---- 1 journey ---- ---- 35 (TW) Retford - Elkesley - Walesby - New Ollerton Mon - Sat 2 journeys 2 hours ---- ---- 36 (TW) Retford - Tuxford - Laxton Mon - Sat ---- 2 hours ---- ---- 37, 37A, 37B Newark - Tuxford - Retford Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins 1 journey ---- 39, 39B Newark - Sutton-on-Trent - Normanton - (Tuxford 39B) Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins ---- ---- 41, 41B (CCVS) Fernwood - Barnby in the Willows - Newark - Bathley - (Cromwell 41B Sat only) Mon - Sat ---- 2 hours ---- ---- 95 Retford - South Leverton - North Wheatley - Gainsborough Mon - Sat ---- 60 mins ---- ---- 190 (GMMN) Retford - Rampton - Darlton (Commuter Link) Mon - Sat 2 journeys 2 journeys -

1An Overview of the North Sea Blowout Problem

I IIASA PROCEEDINGS SERIES Volume 16 Managing Technological Accidents: Two Blowouts in the North Sea IIASA PROCEEDINGS SERIES CARBON DIOXIDE, CLIMATE AND SOCIETY 11 DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS: ISSUES AND Proceedings of an lIASA Workshop Cosponsored CHALLENGES by WMO, UNEP, and SCOPE, Proceedings of an International Task Force February 21-24, 1978 Meeting, Jill Williams, Editor June 23-25, 1980 Garan Fick and Ralph H. Sprague, Jr., Editors 2 SARUM AND MRI: DESCRIPTION AND COMPARISON OF A WORLD MODEL AND A 12 MODELING OF LARGE-SCALE ENERGY NATIONAL MODEL SYSTEMS Proceedings of the Fourth nASA Symposium on Proceedings of the nASA/IFAC Symposium on Global Modeling, Modeling of Large-Scale Energy SYstems, September 20-23, 1976 February 25-29, 1980 Gerhart Bruckmann, Editor W. Hafele, Editor, and L.K. Kirch mayer, Associate Editor 3 NONSMOOTH OPTIMIZATION Proceedings of an nASA Workshop, 13 LOGISTICS AND BENEFITS OF USING MATH March 28-April8, 1977 EMATICAL MODELS OF HYDROLOGIC AND Gaude Lemarechal and Robert Mifflin, Editors WATER RESOURCE SYSTEMS Selected Papers from an International Symposium, 4 PEST MANAGEMENT October 24-26, 1978 Proceedings of an International Conference, A.J. Askew, F. Greco, and J. Kindler, Editors October 25-29,1976 G.A. Norton and C.S. Holling, Editors 14 PLANNING FOR RARE EVENTS: NUCLEAR ACCIDENT PREPAREDNESS AND MANAGE 5 METHODS AND MODELS FOR ASSESSING MENT ENERGY RESOURCES Proceedings of an International Workshop, First lIASA Conference on Energy Resources, January 28-31, 1980 May 20-21, 1975 John W. Lathrop, Editor MkhelGrenon,Edftor 15 SCALE IN PRODUCTION SYSTEMS 6 FUTURE COAL SUPPLY FOR THE WORLD Based on an nASA Workshop, ENERGY BALANCE June 26-29, 1979 Third IIASA Conference on Energy Resources, John A. -

330 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

330 bus time schedule & line map 330 Winkburn - Kirklington - Newark View In Website Mode The 330 bus line (Winkburn - Kirklington - Newark) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newark: 11:30 AM (2) Winkburn: 2:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 330 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 330 bus arriving. Direction: Newark 330 bus Time Schedule 17 stops Newark Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Winkburn Lane, Winkburn Tuesday Not Operational Church, Maplebeck Wednesday 11:30 AM Kersall Lane End, Maplebeck Thursday Not Operational Triumph Road, Eakring Friday 11:30 AM National Grid, Eakring Saturday Not Operational Newark Road, Kirklington School Lane, Kirklington 330 bus Info School Lane, Kirklington Direction: Newark Stops: 17 Trip Duration: 40 min Newark Road, Kirklington Line Summary: Winkburn Lane, Winkburn, Church, Maplebeck, Kersall Lane End, Maplebeck, Triumph Church, Kirklington Road, Eakring, National Grid, Eakring, Newark Road, Kirklington, School Lane, Kirklington, School Lane, Newark Road, Hockerton Kirklington, Newark Road, Kirklington, Church, Kirklington, Newark Road, Hockerton, District District Council, Kelham Council, Kelham, Ollerton Road, Kelham, Rugby Ground, Newark, Newark Castle Railway Station, Ollerton Road, Kelham Newark, Castle Gate, Newark, Bus Station, Newark Rugby Ground, Newark Newark Castle Railway Station, Newark Castle Gate, Newark 35 Castle Gate, Newark on Trent Bus Station, Newark Direction: Winkburn 330 -

27X Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

27X bus time schedule & line map 27X Mansƒeld - Newark View In Website Mode The 27X bus line (Mansƒeld - Newark) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Eakring: 5:40 PM (2) Mansƒeld: 6:34 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 27X bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 27X bus arriving. Direction: Eakring 27X bus Time Schedule 52 stops Eakring Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:40 PM Bus Station, Mansƒeld Tuesday 5:40 PM Quaker Way, Mansƒeld Wednesday 5:40 PM Toothill Lane, Mansƒeld Thursday 5:40 PM Toothill Road, Mansƒeld Friday 5:40 PM Bridge Street, Mansƒeld Rock Court, Mansƒeld Saturday 5:40 PM Great Central Road, Mansƒeld Frederick Street, Mansƒeld Rock Hill, Mansƒeld 27X bus Info Direction: Eakring Reindeer Street, Mansƒeld Stops: 52 Trip Duration: 54 min Maltby Road, Mansƒeld Line Summary: Bus Station, Mansƒeld, Quaker Way, Mansƒeld, Toothill Lane, Mansƒeld, Bridge Street, Jenny Becketts Lane, Mansƒeld Mansƒeld, Great Central Road, Mansƒeld, Frederick Street, Mansƒeld, Reindeer Street, Mansƒeld, Maltby Clifton Grove, Mansƒeld Road, Mansƒeld, Jenny Becketts Lane, Mansƒeld, Clifton Grove, Mansƒeld, Briar Lane, Mansƒeld, Southwell Road West, Mansƒeld, Bellamy Road, Briar Lane, Mansƒeld Mansƒeld, Ransom Business Park, Mansƒeld, Southwell Road West, Mansƒeld Blidworth Lane, Rainworth, Helmsley Road, Southwell Road West, Mansƒeld Rainworth, Farnsworth Avenue, Rainworth, Leeway Road, Rainworth, Pumping Station, Rainworth, Southwell Road East, Rainworth, Station -

20/00873/FULM Proposal: Residential Development of 103 Dwellings And

COMMITTEE REPORT – 3rd NOVEMBER 2020 Application No: 20/00873/FULM Proposal: Residential development of 103 dwellings and associated access and infrastructure Location: Field Reference Number 7108, Eakring Road, Bilsthorpe Applicant: Keepmoat Homes - Miss Elizabeth Woodhouse Agent: Geoff Perry Associates Ltd - Mrs Sinead Rose Registered: 10.06.2020 Target Date: 09.09.2020 Extension of Time Agreed Until 04.11.2020 Website Link: https://publicaccess.newark-sherwooddc.gov.uk/online- applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=documents&keyVal=QB1R8DLBHIG00 The application is being referred to committee as the Officer recommendation is contrary to the objection from the Parish Council. The Site The application site relates to a broadly rectangular plot of land approximately 3.8 hectares in extent to the east of Eakring Road. The site falls within the defined village envelope for Bilsthorpe at the very north eastern extent. The site lies adjacent to the former Bilsthorpe Colliery, which closed in 1997. An old railway line (which has been dismantled) lies to the north of the site, and now appears to be informally used as a footpath/track. There are existing residential curtilages on the opposite side of Eakring Road. Land to the north east is identified as being a site of interest in nature conservation owing to being recognised as an important site for breeding waders. Land to the south is currently in commercial use whilst land immediately to the north and the east is open in nature with woodland screening along the east elevation. Relevant Planning History 17/01139/OUTM - Residential development up to 85 dwellings (Class C3), up to 3,000 sqft (280 sqm) retail development (Class A1), and associated access works including details of a new access junction into the site from Eakring Road. -

IP17 Eakring Inquiry Submission

EAKRING PARISH COUNCIL SUBMISSION INQUIRY: APP/L3055/V/14/3001886 BILSTHORPE BUSINESS PARK My name is Marisha Curry, I am currently Chairman of Eakring Parish Council, of which I have been an elected councillor for 19 years. I have lived in Eakring since 1982. Eakring is a conservation village of some 170 households and 419 parishioners, who are proud of our rural setting, local wildlife, heritage agriculture and tourism. Listed buildings in the village include St Andrew's Church, Eakring Windmill, Walnut Tree Cottage, Hall Farm House and Pond Farm House. Parishioners have raised several concerns regarding the proposed Incinerator, with all bar 2 households signing a petition opposing the application. As Eakring has been working with RAGE many of these concerns may have been raised in more detail in the submission from RAGE, so I apologise for any repetition that may occur. 1 Eakring residents concerns are: air quality and human health. odour and noise, landscape and visual impact, transport, wildlife, tourism and local employment. Air quality and Human Health Eakring is approximately 2 Kms north east of the site, and as the prevailing winds are from the south west and west, would be directly downwind of the incinerator. This has raised concerns relating to odour, noise and emissions, particularly as when the developers were asked, at a consultation evening, what would be the composition of the waste parishioners were told, by the developers, they didn't know. Which obviously raised the question, 'if you don't know what is going in how do you know what is coming out?' As shown in Argus Ecology's Clarification of Air Quality Impacts in the EIA, Eakring will be in direct line of emissions. -

Onshore Oil and Gas Development in Nottinghamshire February 2016 (Updated August 2016)

Onshore oil and gas development in Nottinghamshire February 2016 (updated August 2016) 1 Introduction Oil and gas is important to our economy and as supplies of offshore reserves in the North Sea begin to decline, supplies of onshore reserves are becoming increasingly important. Around one third of our energy requirements are provided by gas for industrial purposes, 1 energy generation and for domestic heating and cooking. Since 2004, the UK has been a net importer of gas. In 2014 45% of UK gas supply was made up of net imports. By 2030 the UK could be importing 75% of the gas we consume 2 assuming new onshore reserves are not developed. Domestic oil production has also declined since reaching a peak in 1999. Currently net imports comprise around 40% of the oil we use. The Department of Energy and Climate Change, (now part of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy), 3 estimate that net imports could increase to 75% of the gas we consume by 2030. The Government believes that developing onshore gas reserves could help fill the gap alongside renewable and nuclear electricity, helping the UK reduce carbon emissions. It could also provide greater security of energy supply and improve energy resilience. The National Planning Policy Framework expects Minerals Planning Authorities should when planning for on-shore oil and gas development, including unconventional hydrocarbons, clearly distinguish between the three phases of development – exploration, appraisal and production- and address constraints on production and processing within areas that are licensed for oil and gas exploration or production. Since the 1940’s Nottinghamshire has extracted oil from across the county and more recently has also extracted gas from disused mine shafts. -

Cycle Routes in Top 9 Places to Visit in Newark & Sherwood Newark & Sherwood

Cycle routes in Top 9 places to visit in Newark & Sherwood Newark & Sherwood Sherwood Pines - offers a fantastic Southwell Trail - famous for Rufford Abbey Contry Park - stroll opportunity for natural cycling. Trails Southwell Minster and the home of the around the 150 acres of tranquil woodland, for every skill level, from a fun day out Bramley Apple, explore the jewel of lake, meadow and gardens. Cafe, deli, with the kids on the Green Family Trail, Nottinghamshire, taking in a traditional shop and new crazy golf, all located on 1to adventurous MTB routes around the 4 array of shops and restaurants. Part of 7 site for a fun-filled day. outer limits of the forest. the Sustran National Cycle Networks nottinghamshire.gov.uk/planing-and- Local adventures forestry.gov.uk/sherwoodpines route 645. sustrans.org.uk environment/country-parks/rufford-abbey for all the family Clumber Park - if you can’t Kelham Hall - located just outside Newark, Sherwood Forest Visitor Centre - the take your bike, this National this is Nottinghamshire’s last undiscovered legendary stomping ground of Robin Trust park is perfect with stately home. Enjoy a great family day out Hood, discover the 450 acre country park its own cycle hire centre with historical tours, walks and cycle rides, including England’s Tree of the Year 2014, 2and trails. 5 indoor and outdoor play areas, cafe and bar, 8 The Major Oak. nottinghamshire.gov.uk/ nationaltrust.org.uk/ campsite and a full events list. planning-and-environment/country-parks/ clumber-park kelham-hall.com sherwood-forest Newark Canal and River New Georgie Twigg Track - Clipstone Park Trail - This 5.7km (3.5miles) - explore the lovely old located just outside of the Newark trail can be enjoyed on foot, on bikes or riverside buildings and and Sherwood area is the newly horseback. -

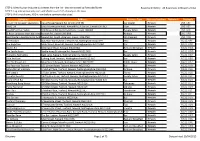

Identify Your Favourite Businesses from the List

STEP 1: Identify your favourite businesses from the list - they are sorted by Postcode/Street Business Directory - All Businesses in Newark v3.xlsx STEP 2: Log into weeconomy.com and check to see if it's already on the map STEP 3: If it's not shown, ADD it now before someone else does! Company Address Business Type Business Location Nationals Postcode Lincoln Volkswagen Specialists Aqua House/Newark Rd, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Car Dealer - Newark LN5 9EJ Vital2 Ltd Lincoln Enterprise Park, Newark Rd, Aubourn, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Gym - Newark LN5 9EJ HeadOffice Hair Salon 310 Newark Rd, North Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 8JX Beauty Salon - Newark LN6 8JX SJ Bean Longcase clock dial restorationNewark and Rd, clock Lincoln repairs LN6 8RB Antique - Newark LN6 8RB Best Western Bentley Hotel And SpaNewark Rd, South Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 9NH Dry Cleaners - Newark LN6 9NH M H Motors Staunton Works/Unit 1 Newark Rd, Nottingham NG13 9PF MOT - Newark NG13 9PF The Angel Inn Main Street, Kneesall, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0AD Bar - Newark NG22 0AD Howes R J Kirklington Road, Newark NG22 0DA Bed and Breakfast - Newark NG22 0DA The Saville Arms Saville Arms/Bilsthorpe Rd, Newark NG22 0DG Bar - Newark NG22 0DG Thoresby Aesthetica Back Lane, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0DJ Beauty Salon - Newark NG22 0DJ Olde Red Lion Eakring Road, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EG Bar - Newark NG22 0EG The Old Plough Inn Main Street, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EZ Public House - Newark NG22 0EZ The Fountain Tuxford 155 Lincoln Road, Tuxford, Newark NG22 0JQ Bar - Newark NG22 0JQ Sally -

Eakring Windfarm Planning Application

meeting Cabinet date 11th October 2006 agenda item number Report of the Leader Strategic planning observations on planning application for five wind turbines at land to the west of Blidworth Lane, Rainworth, Nottinghamshire Purpose of the Report 1. To seek approval for comments set out in this report to be sent to Newark and Sherwood District Council in response to the request for strategic planning observations on the above planning application. Introduction 2. On 3rd July 2006 a planning application was submitted to Newark and Sherwood District Council for a windfarm at land to the west of Blidworth Lane, Rainworth, Nottinghamshire. 3. Nottinghamshire County Council has been consulted for strategic planning observations on the application and this report compiles responses from Departments involved in providing comments and observations on such matters. On the basis of Cabinet’s decision, comments will be sent to Newark and Sherwood District Council in response to this consultation. 4. The planning application is accompanied by an Environmental Statement (ES) and a Planning Statement. This report is based on the information submitted with the application in the context of national, regional and local policy. 5. Through the consideration of the ES a number of omissions and incorrect assumptions have been identified. Most of these matters could be addressed through the submission of further information or reassessment of the situation based on a different assumption. The issues are raised in the relevant sections of the report below. 6. Although there are instances where not all of the information is available at the present time, it is nevertheless important that Nottinghamshire County Council take this opportunity to provide strategic planning observations to Newark and Sherwood District Council, albeit that they may be made subject to caveats regarding the outstanding information. -

Cycle Rides in Nottinghamshire

Cycle Rides in Nottinghamshire Pretty Villages Overview: A 30 mile ride from Southwell, mainly on quiet country roads. The route passes through many pretty villages in north east Nottinghamshire, including Laxton, the only village in England to still use the open field farming method. Start and Finish: Free long stay car park near Southwell Leisure Centre. NG25 0LW. Turn right onto A612, towards Southwell. At junction turn right onto Westgate. Straight on at mini roundabout then left onto Queen Street. Right onto the Ropewalk then right again at bottom, mini roundabout. 1 mile. Next left towards Hockerton and follow road for 2.5 miles to the A617. Turn left and then almost immediately right towards Knapthorpe on Caunton Road. Passed Knapthorpe and then cross the A616 at 6 miles, towards Caunton. Follow road into Caunton, turn right onto Main Street, then right again onto Norwell road. Take left turn, for Norwell, at 7.3 miles. Right into Norwell at 8.7 miles. Follow road round to the left through the centre of Norwell. The left, towards Ossington at 9 miles. Left onto Ossington Road at 11 miles. Turn right towards Moorhouse and Egmanton at 11.6 miles. At Moorhouse take right fork towards Egmanton, Weston Road. 14.2 miles, turn left on Weston Road and follow in Egmanton. In Egmanton take the left onto Laxton Road and then turn right onto Main Street, which becomes Kneesall Road at 17 miles. Stay on Kneesall Road into until crossroads at 18.5 miles. Turn right here, Ossington Road, into Kneesall. Keep going, through Kneesall, on the Ossington Road, until reaching the A 616.