Chapter 7. Continuity and Change: Labourers' Lives In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superfast Worcestershire Spring 2017 Newsletter

Click here to sign up now! Spring 2017 News Welcome to the spring edition of our Superfast Worcestershire newsletter “Superfast Worcestershire is taking coverage even further than we had originally envisaged. Thousands more Worcestershire households and businesses can look forward to a fibre broadband boost thanks to a £3.7 million pound expansion. This latest announcement shows the commitment of the partnership to ensuring that Worcestershire is connected. It is great news that more people will be able to benefit from the new communications technology that is often taken for granted by those who already have access to superfast speeds.” Cllr Ken Pollock, Cabinet Member responsible for Economy, Skills and Infrastructure With spring around the corner we’re delighted to announce that around 245,000 premises in Worcestershire are able to connect to fibre broadband. Of these, over 62,000 premises are able to connect as a result of the Superfast Worcestershire Broadband Programme, and the number continues to rise. In this edition of our newsletter, find out: • How we’re expanding fibre broadband coverage • Which Worcestershire businesses are loving fibre broadband • Where we are delivering Fibre to the Premises ...and much, much more! Superfast Worcestershire is a partnership between Thousands more households and businesses to get fibre broadband boost thanks to £3.7 million pound expansion We are delighted to announce a major £3.7 million pound expansion that will enable over 3,000 more households and businesses to access superfast broadband for the first time. Additional communities across all six districts in Worcestershire have been earmarked for upgrades as part of the multi-million pound roll-out, including parts of Wickhamford, Throckmorton, Wick, Heightington, Teme Valley including Eardiston and Stockton on Teme, Holt Fleet, Shelsley Beauchamp and Berrow Green. -

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire Nils Wilkes Acknowledgements I first began this project in September 2012 having noticed a number of limekilns annotated on the Ordnance Survey County Series First Edition maps whilst carrying out another project for the Historic Environment Record department (HER). That there had been limekilns right across Worcestershire was not something I was aware of, particularly as the county is not regarded to be a limestone region. When I came to look for books or documents relating specifically to limeburning in Worcestershire, there were none, and this intrigued me. So, in short, this document is the result of my endeavours to gather together both documentary and physical evidence of a long forgotten industry in Worcestershire. In the course of this research I have received the help of many kind people. Firstly I wish to thank staff at the Historic Environmental Record department of the Archive and Archaeological Service for their patience and assistance in helping me develop the Limekiln Database, in particular Emma Hancox, Maggi Noke and Olly Russell. I am extremely grateful to Francesca Llewellyn for her information on Stourport and Astley; Simon Wilkinson for notes on Upton-upon-Severn; Gordon Sawyer for his enthusiasm in locating sites in Strensham; David Viner (Canal and Rivers Trust) in accessing records at Ellesmere Port; Bill Lambert (Worcester and Birmingham Canal Trust) for involving me with the Tardebigge Limekilns Project; Pat Hughes for her knowledge of the lime trade in Worcester and Valerie Goodbury -

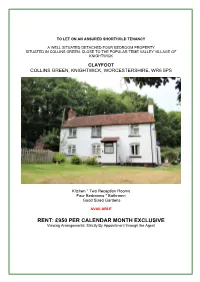

950 PER CALENDAR MONTH EXCLUSIVE Viewing Arrangements: Strictly by Appointment Through the Agent

TO LET ON AN ASSURED SHORTHOLD TENANCY A WELL SITUATED DETACHED FOUR BEDROOM PROPERTY SITUATED IN COLLINS GREEN, CLOSE TO THE POPULAR TEME VALLEY VILLAGE OF KNIGHTWICK CLAYFOOT COLLINS GREEN, KNIGHTWICK, WORCESTERSHIRE, WR6 5PS Kitchen * Two Reception Rooms Four Bedrooms * Bathroom Good Sized Gardens AVAILABLE RENT: £950 PER CALENDAR MONTH EXCLUSIVE Viewing Arrangements: Strictly By Appointment through the Agent CLAYFOOT, COLLINS GREEN, KNIGHTWICK, WORCESTERSHIRE, WR6 5PS Approximate Mileages: - Bromyard 5.5 * Worcester 9 * Birmingham 30 * M5 Junction 7 -11 SITUATION The property Clayfoot is situated in Collins Green which is close to the small village of Knightwick and the popular Talbot Inn. The property is within easy reach of the market town of Bromyard as well as the City of Worcester, which between them offer extensive shopping, leisure and educational facilities. Within the village of Knightwick there is the Public House, Doctors Surgery and Butchers. The nearby villages of Whitbourne, Alfrick and Martley all benefit from village stores. The accommodation is described in more detail as follows: DESCRIPTION The property comprises a detached dwelling located in an elevated rural position with extensive views over the Worcestershire countryside to the Breden Hills. The property is situated in the Martley Chantry School catchment area. The accommodation comprises a four bedroom dwelling with two Reception Rooms, Kitchen and Utility Room. Outside is a Double Garage and pleasant garden area with new patio. The accommodation within comprises KITCHEN 12’9 x 7’11 (3.90m x 2.41m) with kitchen units to include full range of base units with breakfast bar, Hotpoint Ultima electric cooker and Rayburn oven. -

8.9 MHDC Sheduled Weekly List Of

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 19/10/2020 to 23/10/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00943/FUL Location: The Grange, Alfrick, Worcester, WR6 5HH Proposal: Change of use, conversion and extension of pigsty to 1 bed holiday accommodation. Decision Date: 20/10/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs S Tolley Agent: Miss Lucy Righton The Grange Brickyard Cottage Patches Farm Hill Furze Road Alfrick Bishampton Worcestershire Pershore WR6 5HH WR10 2NA Parish: Alfrick CP Ward: Alfrick and Leigh Ward Case Officer: Lee Walton Expiry Date: 03/09/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862314 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/01230/TPOA Location: Little Acorns, Knightwick Road, Alfrick, Worcester, WR6 5HX Proposal: Reduce canopy of one oak tree by 30%, as detailed on application form and in accompanying information Decision Date: 20/10/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs Lee Agent: Nicholas Denley Little Acorns, Knightwick Road 5 Folly Crescent, Folly Road Alfrick Alfrick WR6 5HX Worcester WR65HN Parish: Alfrick CP Ward: Alfrick and Leigh Ward Case Officer: Chris Lewis-Farley Expiry Date: 02/12/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565177 Case Officer Email: chris.lewis- [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 20 Application No: 20/01520/TPOA Location: Little Acorns, Knightwick Road, Alfrick, Worcester, WR6 5HX Proposal: Fell one oak tree, as detailed on application form and in accompanying -

Triangle April 04.Qxd 25/09/2015 14:47 Page 1 Teme TRIANGLE Clifton Upon Teme • the Shelsleys • Lower Sapey October 2015

96261 Teme Triangle October 2015_Triangle April 04.qxd 25/09/2015 14:47 page 1 Teme TRIANGLE Clifton upon Teme • The Shelsleys • Lower Sapey October 2015 Zoe Dallow in Nepal In this edition 4 Church Matters on refugees 4 The season of Harvest 4 Events coming up in our villages 4 Parish Council news www.temetriangle.net Free to Residents 96261 Teme Triangle October 2015_Triangle April 04.qxd 25/09/2015 14:47 page 2 The Lawson family who are moving from The Bridge to The Baiting House EDITOR: Judie Welsh, Email: [email protected] WEBSITE/CLIFTON NEWS: Jerry Johns: 01886 812 304 [email protected] ADVERTISING/SPONSORSHIP: Andrew and Anna Brazier 01886 887 898 [email protected] LOWER SAPEY NEWS: Marion West 01886 853 249 [email protected] Opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the editorial team. We are not responsible for goods and services advertised. Your contributions may be altered or edited at the discretion of the editor of the month, and the editorial team. Our front cover picture shows: Zoe Dallow from Lower Sapey in Nepal 2 96261 Teme Triangle October 2015_Triangle April 04.qxd 25/09/2015 14:47 page 3 WELCOME to the Autumn and our October edition! This is one of my favourite times of the year, who could fail to delight in a sunny autumn with an abundant harvest? Apples, damsons and hops, the crops that define our valley more than any others, are plentiful and at this time many of us are stockpiling wood ready for the inevitable cold days. -

Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area .............................................................. 3 2. Table of Resources ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. 'See Under' List ............................................................................................................................. 23 4. Glossary of Terms ........................................................................................................................ 33 2 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area The following is a guide to the types of records we hold and the areas we may cover within the Self Service Area of the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service. The Self Service Area has the same opening hours as the Hive: 8.30am to 10pm 7 days a week. You are welcome to browse and use these resources during these times, and an additional guide called 'Guide to the Self Service Archive Area' has been developed to help. This is available in the area or on our website free of charge, but if you would like to purchase your own copy of our guides please speak to a member of staff or see our website for our current contact details. If you feel you would like support to use the area you can book on to one of our workshops 'First Steps in Family History' or 'First Steps in Local History'. For more information on these sessions, and others that we hold, please pick up a leaflet or see our Events Guide at www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas. About the Guide This guide is aimed as a very general overview and is not intended to be an exhaustive list of resources. -

September 2018 Temeteme TRIANGLETRIANGLE Clifton Upon Teme • the Shelsleys • Lower Sapey

September 2018 TemeTeme TRIANGLETRIANGLE Clifton upon Teme • The Shelsleys • Lower Sapey St Kenelm’s Bells 350th Anniversary In this edition Y Win A Thumb-Stick Raffle Y Shelsleys’ Stalwarts Retire Y OPEN Clifton Bells 350th Anniversary Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps www.temetriangle.net Free to Residents www.temetriangle.net 1 Pictured outside All Saints Church, Barry Hodgetts holds the unique crab apple cane that can be won (see page 3). EDITOR: Jerry Johns WEBSITE/CLIFTON NEWS: 01886 812304 [email protected] SHELSLEYS NEWS: Michelle Whitefoot: [email protected] LOWER SAPEY NEWS: Marion West 01886 853249 [email protected] ADVERTISING/SPONSORSHIP: Andrew and Anna Brazier 01886 887898 [email protected] Opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the editorial team. Teme Triangle is not responsible for goods and services advertised. Front Cover Picture Members of the Martley group of bellringing churches joined members of St Kenelm’s ringing band to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the installation of the church bells in Clifton (see page 3). 2 www.temetriangle.net CLIFTON BELLS CELEBRATION DAY St Kenelm’s Church in Clifton celebrated the 350th birthday of its bells in July. The day started with a Holy Communion service at 10.30am in which Canon David Sherwin gave thanks for the bells. It was also a special service for local deacon, Rev Becky Elliott, because she took her first communion service. Afterwards, local parishioners were invited to a barbecue the Rectory, followed by a dog show and a bell competition. -

NOTICE of UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Councillors

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Malvern Hills Election of Councillors for Abberley on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Councillors for Abberley. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDREW 59 The Common, Abberley, Kate Worcester, WR6 6AY EBERLIN Jacobs Well, Suffolk Lane, Cathie Abberley, Worcestershire, WR6 6BE EDEN Lower Oak, Apostles Oak, Tony Abberley, Worcestershire, WR6 6AD GIBSON Ballards Mill, Old Yates Farm, Jim Stockton Road, Abberley, WR6 6AT GOODMAN Old Yates Farm, Abberley, Richard Michael Worcester, WR6 6AT JUCKES Hop Pocket, Bank Lane, Abberley, Alan Worcs, WR6 6BQ KNIGHT The Old Village Stores, The Catherine Village, Abberley, Worcestershire, WR6 6BN NOTT Field Farm, Abberley, Worcester, Farmer Trevor WR6 6AE Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Jack Hegarty Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Room F7, Council House, Avenue Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 3AF NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Malvern Hills Election of Councillors for Alfrick on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Councillors for Alfrick. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ASHTON Rosevine, Lulsley, Knightwick, Richard Alexander Worcester, WR6 5QP BRADLEY (Address in Malvern Hills) Carol Judith BROWN Millham Farm, Alfrick, Worcester, Barbra Gerda WR6 5HS COOPER Midsummer House, Alfrick, Andrew -

Parish Registers on Microfilm at the Hive Worcestershire Archive And

Parish Registers on Microfilm at The Hive Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service 2012 Introduction to the Parish Register Handlist The Hive holds parish registers for Worcestershire dating from the mid 16th century onwards. The church registers contain records of Baptisms, Marriages and Burials. These records are a major focus of study for family, local and social history, as they contain a wealth of information. As such, much of the information has been copied for ease of access and use. This handlist is a guide to what is currently available in our Self-service area. What Information does the Handlist provide? The name of the village. The Civil and Ancient parishes are often the same but there may have been changes over time. The name of the church from which the registers originated. This can be useful if there is more than one in a particular parish. For example, in Worcester City there are several parish churches. The name of the civil parish which now encompasses the ancient parish. Information on what register copies are available on microfilm. Dates of any transcriptions either in volumes or available on CD. Please see our handlist to parish register transcriptions and our list of CD holdings for further details The Notes column provides further information such as where parishes have been formed out of others. The registers we hold largely relate to Worcestershire, but as the diocese of Worcester has changed over the centuries we may hold registers from other counties too. Some parishes will return the result 'no information'. This usually means that we do not hold the registers for that parish. -

September 2011 Teme Valley Shufflers Line Dancing: 7Pm Martley Memorial Hall Enq

Memorial Hall Wichenford Ladies’ Fellowship: 2.30pm 2nd Tuesday in the month (usually) Martley Toddler Group: 1st and 3rd Tuesdays (term time) 10.30am Martley Memorial Hall Wednesdays Volume 21 No. 4 September 2011 Teme Valley Shufflers Line Dancing: 7pm Martley Memorial Hall Enq. Jeff & Advertise in The Villager: Aileen Thelma 01886 821772 Parker. 01886 888456 Martley Folk Club: 1st Wednesday in Editor: Gail Dawson (01886 889180) the month at The Talbot, Knightwick and Editorial Team: Martley Alan Boon (01886 3rd Wednesday at The Admiral Rodney 888527), Kate King (01886 888439) Martley WI: 2nd Wednesday in the Wichenford Janet Andrews (01886 888303), month 7.30pm Heaton House Sheila Richards (01886 888378) Distribution: Martley George & June Lawrence Thursdays (01886 821064) Wichenford Karen Furber Wichenford Wine Club: 3rd Thursday in (01886 888449) the month Contact The Villager: Leave articles at Martley Post Office, call Janet or Sheila Martley & District Horticultural (Wichenford) or email the Editor at Society: last Thursday in the month [email protected] 7.30pm Martley Memorial Hall Opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of The Villager. The Villager See Church Words p. 27 for details of services cannot be held responsible for any goods or services advertised in the magazine. See articles for details of special events AND changes of time/date/venue of regular events Regular events in Martley and See the Diary page on www.martley.org.uk for Wichenford: a complete listing of all forthcoming events (that the Diary page editor knows about) Sundays See page 28 for contact details of organisations 2nd Sunday in the month: Teme Valley Farmers Market for local Articles to go in The Villager must be produce 11am The Talbot, Knightwick submitted by the 1st of the Martley Ramblers meet Church car park previous month 3rd Sunday in the month: Path-or-Nones meet 9.30am Martley Memorial Hall car park to help maintain the local footpaths Mondays Rhythm Time: 9.30-11.30am Martley Memorial Hall Enq. -

Alfrick & Leigh Ward Profile

Autumn 2016 This is one of a series of profiles which cover all of the 22 wards in the Malvern Hills district. It is designed to assist in identifying the key challenges in the ward and to help ensure a better understanding of the community. PopulationPopulation Population 2011 3507 Households 1649 1750 17571757 1750 Life expectancy: Male 77.4 MaleMale FemaleFemale 24.2%24.2% ofof peoplepeople areare 65+65+ Life expectancy: Female 81.6 23.5% of people are 65+ 23.5% of people are 65+ Average household size 2.4 14th14th highesthighest ofof thethe 2222 wardswards Area (sq. miles) 18.2 17.6%17.6% areare underunder 1818 17th17th highesthighestofof thethe 2222 wardswards Population density (persons per sq. mile) 193 Education Health Crime (April 2015 -March 2016) 39% 19% of people have 82.4% good or very good 30 Crimes per 1000 people people qualified without the 10th lowest of the 22 wards to level 4 any vs 80.7% ASB incidents or above qualifications in Malvern Hills 19 per 1000 34% Malvern Hills 20% & 81.4% the 9th lowest of in Worcestershire the 22 wards 27% England 23% Car ownership Housing Deprivation of households Properties that are detached 5% have no car or the 3rd lowest of the 22 wards of households in Alfrick & Leigh are deprived in 2 or more dimensions Malvern Alfrick England 14% 17% 44% & Leigh 22% 7th lowest of the 22 wards Worcestershire Malvern Hills 60% There are high levels of oil central heating and houses that fail to meet the decent homes standard An increase in the percentage of people aged 60+ and increasing levels of unpaid carers Large distances to community amenities for many of the population and a reliance on the 3rd highest levels of car ownership of the wards in Malvern Hills. -

Land Tax Handlist Version 1

Tax Records On Microfilm At The Hive Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service 2012 1 Contents Land Tax Records………………..1 Hearth Tax Records……………..34 Poll Tax Records………………...98 2 Land Tax Returns 1781-1832 On Microfilm 3 Contents Introduction to Land Tax Returns 5 How to use this handlist 6 Section 1: By date 7-14 Section 2: By hundred 15-31 Blakenhurst 16 - 17 Doddingtree 18 - 19 Lower Halfshire 20 - 21 Upper Halfshire 22 - 23 Middle and Lower Oswaldslow 24 - 25 East Oswaldslow 26 - 27 Lower Pershore 28 - 29 Upper Pershore 30 - 31 4 Introduction to Land Tax Returns Land Tax Assessment was established in 1692 and was levied on land with an annual value of more than 20 shillings. It was first collected in 1693 and continued to be collected until 1963. Before 1780 Land Tax Assessments are rare but from then until 1832 duplicates of the Land Assessments had to be lodged with the Clerk of the Peace and are to be found in County Quarter Sessions records. In 1798 the tax was fixed at 4 shillings in the pound and this was made as a permanent charge on the land. The landowners were given the choice of paying 15 years of tax in a lump sum and by 1815 one third of landowners had taken this option. Worcestershire Land Tax Returns can give: Rental value of the owner’s property. Names of owners and copyholders. Names of occupiers. Names or description of property or estate. The amounts of tax levied. Those owners exonerated from paying the tax annually.