Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting a Wide Net: How Ngos Promote Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets (Tanzania)

Casting A Wide Net: How NGOs Promote Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets Tanzania NGO Alliance Against Malaria May 2004 alaria M CORE STORIES FROM THE FIELD The Child Survival Collaborations and Resources Group (The CORE Group) is a membership associa- tion of more than 35 U.S. private voluntary organizations that work together to promote and improve primary health care programs for women and children and the communities in which they live. The CORE Group’s mission is to strengthen local capacity on a global scale to measurably improve the health and well being of children and women in developing countries through collaborative NGO action and learning. Collectively, its member organizations work in over 140 countries, supporting health and devel- opment programs. The CORE Malaria Working Group assists CORE member organizations and others to improve malaria prevention and case management programs through the following country-level activities: 1) establish- ment of NGO secretariats to enhance partnerships and collaborative action, 2) organization of workshops for learning and dissemination, and 3) documentation of innovative practices and lessons learned. The CORE Group-supported Tanzania NGO Alliance Against Malaria (TaNAAM) was founded in May 2003 to coordinate the activities of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) on Roll Back Malaria and Integrated Management of Childhood Illness initiatives. Founding members include Africare, the African Medical and Research Foundation, CARE, Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre, International Rescue Committee, Médecins Sans Frontières, Plan International, Population Services In- ternational, and World Vision. TaNAAM works to strengthen collaboration between member NGOs, accelerate implementation and expansion of best practices, and document and disseminate promising in- novations. -

Ghost Signs Are More Than Paintings on Brick

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2020 ghost signs are more than paintings on brick Eric Anthony Berdis Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons © Eric Anthony Berdis Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6287 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©2020 All Rights Reserved ghost signs are more than paintings on brick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University Eric Anthony Berdis B.F.A. Slippery Rock University, 2013 Post-baccalaureate Tyler School of Art, 2016 M.F.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2020 Director: Hillary Waters Fayle Assistant Professor- Fiber and Area Head of Fiber Craft/ Material Studies Department Jack Wax Professor - Glass and Area Head of Glass Craft/ Material Studies Department Kelcy Chase Folsom Assistant Professor - Clay Craft/ Material Studies Department Dr. Tracy Stonestreet Graduate Faculty Craft/ Material Studies Department v Acknowledgments Thank you to my amazing studio mate Laura Boban for welcoming me into your life, dreams, and being a shoulder of support as we walk on this journey together. You have taught me so much and your strength, thoughtfulness, and empathy make me both grateful and proud to be your peer. Thank you to Hillary Fayle for the encouragement, your critical feedback has been imperative to my growth. -

Hail to the Chief of Land Court

SATURDAY, JULY 13, 2019 By Bella diGrazia Swampscott resident ITEM STAFF SWAMPSCOTT — While loud noises annoy making noise about noise some, it’s different for Neil Donnenfeld. The sounds are excruciatingly painful for him. Donnenfeld’s hearing troubles began about sev- en years ago, after he lost a third of his hearing. He was diagnosed with acous- tic neuroma, a benign brain tumor that sits on the hearing nerves. Treat- ment included radiation. His world turned upside down, which is why he left his beloved corporate job and dedicated his time to researching noise pol- lution. His goal? To raise awareness about the in- door and outdoor sounds that hurt people with hearing disabilities. “Noise was off my radar and irrelevant to my life until six years ago,” he said. “The effects of noise State Land Court Chief Justice for me throughout the day ITEM PHOTO | SPENSER HASAK are cumulative and there’s Gordon H. Piper swore in Christi- A motorcycle drives past Neil Donnenfeld’s house on Humphrey Street in a certain amount I can na Geaney of Lynn as Land Court Swampscott. Donnenfeld, who is noise disabled, wants to start raising aware- handle before I experience Chief Title Examiner. ness about the environmental hazards of loud noises, especially for people with hearing disabilities. SWAMPSCOTT, A3 Hail to By Bridget Turcotte ITEM STAFF Nahant ready for a the chief of NAHANT — Rowers will party like it’s 1971 on Saturday with a longtime Grand (Pram) old time Land Court tradition created for the fun and companionship of Lynn’s Christina Geaney is the new chief the town. -

The Trendera Files

THE TRENDERA FILES Trendera THE POST VIRAL AGE Volume 8, Issue 2, Spring 2017 THE TRENDERA FILES: THE POST VIRAL AGE CONTENTS FUTURE-FORWARD INTRO 4 MARKETING 36 SOCIAL MEDIA MARKETING CHEAT STAT HIGHLIGHTS 6 SHEET 43 07 Would You Rather... 44 Facebook 08 Marketing 46 Instagram 12 Social Media Marketing 48 Snapchat 16 Shopping 50 YouTube 19 Getting Political 20 Entertainment NOW TRENDING 52 Trendera53 Lifestyle SOCIETAL SHIFTS 25 59 Entertainment 26 The Post-Viral Age 62 Fashion/Retail 28 May (A)I Help You? 65 Tech 30 Protest Is The New Brunch 32 California Rising 34 Over Worked & Over Work 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S HOT 69 70 Kids 72 Teens 74 Millennials 76 Actors 78 Actresses 80 Online Influencers 82 Digital Download KNOW THE SLANG Trendera84 STATISTICS 87 90 13-50 Year Olds 150 8-12 Year Olds 3 THE TRENDERA FILES: THE POST VIRAL AGE Beacons, Big Data, Facebook, Google... We have access to more information than ever, yet it seems things aren’t getting any easier for marketers—in fact, one in four teens would rather go to JAIL than never be able to skip an ad again. We’ve entered the Post-Viral age of marketing, where reach does not equal engagement and engagement does not equal profit—just ask Snapchat. After all, today’s consumers aren’t just savvy, they’re finicky, too. They can spot brands’ tactics from miles away because they’re using the same ones to build their own. They want marketers to speak their language, but are ruthlessly unforgiving when they miss the mark, whether it’s by a little (Gucci memes) or a lot (Pepsi trying to be #woke). -

Chretien De Troyes' Erec Et Enide and Cistercian Spirituality

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1984 Chretien de Troyes' Erec et Enide and Cistercian Spirituality Patricia Ann Quattrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Quattrin, Patricia Ann, "Chretien de Troyes' Erec et Enide and Cistercian Spirituality" (1984). Master's Theses. 1554. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1554 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRETIEN DE TROYES' EREC ET ENIDE AND CISTERCIAN SPIRITUALITY by Patricia Ann Quattrin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The Medieval Institute Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1984 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHRETIEN DE TROYES' EREC ET ENIDE AND CISTERCIAN SPIRITUALITY Patricia Ann Quattrin, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1984 Many critics confess to a "vague uneasiness" with the meaning of Chretien de Troyes' Erec et Enide, especial ly with the motivation for Erec's adventures. Such critics as D. W. Robertson, E. Talbot Donaldson, and Northrup Frye posit methodological approaches to the meaning and under standing of vernacular romances. However, researching Cis tercian monasticism, especially William of St. Thierry, I noted similarities between and parallels in the structure of a spiritual quest for God and a model of the secular quest found in Chretien de Troyes' Erec et Enide. -

Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien De Troyes Through Bernard of Clairvaux

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2016 Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux Carrie D. Pagels University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Christianity Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pagels, Carrie D., "Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3732 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Carrie D. Pagels entitled "Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in French. Mary McAlpin, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: John Romeiser, Anne-Helene Miller, Mary Dzon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Carrie D. -

Where Is Miike Snow? I Miss Them Old Dogs and New Tricks Tasia Kuznichenko Is Snowed by the Sounds of This Intercontinental Band

Honi Soit WEEK 8, SEMESTER 1, 2021 FIRST PRINTED 1929 Inside Glebe Markets / P 12 Higher education in Where did Miike Student General Meetings: the Sinosphere / P 16 Snow go? / P 14 then and now / P 6 Acknowledgement of Country Letters Former President Puzzled call the police because they don’t efficiency — extra limbs do wonders Honi Soit is published on the Wallumedegal people, we are the of First Nations people is perpetuated to be reflective when we fail to do so. understand mole language, but if for your typing speed. Sydney Uni’s SAUCIEST socialite! sovereign land of the Gadigal People beneficiaries of ongoing colonial and enabled by the government, who We commit to being a counterpoint Dear Honi Soit editors, they did, I would have told them all of the Eora Nation, who were amongst dispossession. The settler-colonial push ahead with the forced removals to mainstream media’s silencing of about your evening racket. There I have recently uncovered some Dear plumptious beauties, the first to resist against and survive project of ‘Australia’ and all its of Aboriginal children from their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander You bullies should spend more time are laws against this sort of thing GIPA documents which suggest the violence of colonisation. This institutions, including the University, families, their Country, and their people. We remain cognisant that on your crosswords and less time you know! I am not an unreasonable that Stephen Garton is aware of our land was taken without consent and are built on the exclusion of First cultures. Aboriginal peoples are the Honi’s writers and readership are making my life misery. -

University of Nevada, Reno the Educational Effectiveness of Gülen-Inspired Schools: the Case of Nigeria a Dissertation Submitte

University of Nevada, Reno The Educational Effectiveness of Gülen-inspired Schools: The Case of Nigeria A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning by HASAN AYDIN Dr. Stephen Lafer/Dissertation Advisor May, 2011 © by Hasan Aydin 2011 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by HASAN AYDIN entitled The Educational Effectiveness of Gülen-inspired Schools: The Case of Nigeria be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Stephen K. Lafer, Ph.D., Advisor Jennifer Mahon, Ph.D., Committee Member Michael Robinson, Ph.D., Committee Member Susan Chandler, Ph.D., Committee Member Murat Yuksel, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph.D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i Abstract This qualitative case study examined the perceptions of the efficacy of the Gülen educational initiative and provides an analysis of the educational viability of ―Gülen- inspired‖ schools in Nigeria using interviews of members of four groups of stakeholders in the Nigerian Turkish International Colleges (NTIC). This study employed a qualitative methodology with case study approach in which twenty-two individuals participated, among them three administrators, seven Nigerian/Turkish teachers, eight students, and four‘ parents. Interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis and in small focus groups to elicit the lived experience of people involved with the schools. The interview questions concerned the effectiveness of Gülen-inspired schools in Nigeria and their role positive educational change in this country. Data collection consisted beyond the interviews was collected through classroom observations, field notes, and engagement with school provided documents. -

Aspects of the Performative in Medieval Culture Trends in Medieval Philology

Aspects of the Performative in Medieval Culture Trends in Medieval Philology Edited by Ingrid Kasten · Niklaus Largier Mireille Schnyder Editorial Board Ingrid Bennewitz · John Greenfield · Christian Kiening Theo Kobusch · Peter von Moos · Uta Störmer-Caysa Volume 18 De Gruyter Aspects of the Performative in Medieval Culture Edited by Manuele Gragnolati · Almut Suerbaum De Gruyter ISBN 978-3-11-022246-3 e-ISBN 978-3-11-022247-0 ISSN 1612-443X Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aspects of the performative in medieval culture / edited by Manuele Gragnolati, Almut Suerbaum. p. cm. Ϫ (Trends in medieval philology, ISSN 1612-443X ; v. 18) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-3-11--022246--3 (print : alk. paper) ISBN 978-3-11--022247--0 (e-book) 1. Literature, Medieval Ϫ History and criticism Ϫ Theory, etc. 2. Authorship Ϫ History Ϫ To 1500. 3. Civilization, Medieval. 4. Philosophy, Medieval. I. Gragnolati, Manuele. II. Suerbaum, Almut. PN88.A77 2010 8011.9510902Ϫdc22 2010005460 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ” 2010 Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/New York Printing: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ϱ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface The current volume is the result of close collaboration between a group of colleagues who discovered in the course of college lunches that we shared more than day-to-day responsibility for undergraduate teaching. Indeed, once we started discussing our research interests in a series of informal and more structured workshops and colloquia, it became evident that notions of performance had a bearing on what at first sight seemed quite diverse subjects and disciplines. -

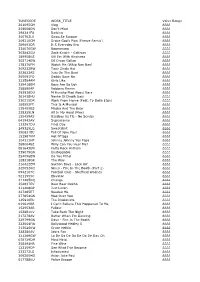

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

A Place for Women to Call Home in Peabody

SATURDAY, JULY 6, 2019 Demakes providing a new foundation for Agganis By Steve Krause person in its 63-year history to pre- Boston University. At the time of the next 26 years, until Andrew ITEM STAFF side over the Agganis Foundation. his death at age 26 of a pulmonary Demakes took over last fall. Family patriarch Attorney embolism on June 27, 1955, he was The Demakis/Demakes fami- LYNN — Family and community Charles Demakis prompted The a rst baseman for the Red Sox. lies have a long history with the have always been important to the Demakes/Demakis families. Item and the Red Sox to establish Agganis’ coach and mentor, the foundation. Charles Demakis’ son, Thomas L. Demakes and his sons the foundation in 1955 after the late Harold Zimman, a sports pub- Attorney Thomas C. Demakis, is work together at Old Neighborhood untimely death of Harry Agganis, lisher and U.S. Olympic commit- the immediate past chairman and Foods, and they were educated to- who is considered by many to be teeman, ran the foundation for 37 Thomas L. Demakes is a trustee gether, literally. Now, his youngest the greatest athlete in the history years until handing off in 1992 to and one of the foundation’s most son, Andrew, 38, has become in- of Lynn. “The Golden Greek” was a Edward M. (Ted) Grant, now The generous benefactors. volved in another family undertak- star in football, baseball and bas- Item’s publisher. Grant presided ing: He has become only the third ketball at Classical and, later, at over and grew the foundation for DEMAKES, A3 Andrew Demakes A place for women to Saugus seeks call home in Peabody the road to safety for drivers and pedestrians By Bridget Turcotte ITEM STAFF SAUGUS — Residents can learn about the results of the town’s speed-limit study Monday night. -

Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts

RICHMOND HILL CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS RICHMOND HILL CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS RICHMOND HILL CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 2OI8-2OI9 SEASON Many Hands Make Art Work 2OI8-2OI9 RICHMOND HILL CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS SEASON Many Hands Make Art Work 1 Season Sponsor 2OI8-2OI9 SEASON Many Hands Make Art Work 2OI8-2OI9 SEASON Many Hands Make Art Work Thank You The Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution of our sponsors. Season Sponsor Series Sponsor Education Series Sponsor Official Hotel Sponsor Official Supplier of Musical Instruments 01 7 August 2017 Printed colours 186 Large logo: over 60mm wide File name tim_hortons_master_logo Client Tim Hortons Project Master Logo Artworker RS Warwick Building, Avonmore Road London, W14 8HQ, United Kingdom +44 (0)20 8994 7190 Official RHCPA Photographer Small logo: 30–60mm wide Minimum size of small logo Maximum size of small logo 30mm wide 60mm wide Show Sponsor 2 Table of Contents Visit page 9 for Theatre Series Packages. 4 Messages 27 The Paper Bag Princess: A Musical 5 RHCPA Speaker Series 28 I Mother Earth / Finger Eleven 6 Suite Thursday Series 29 Art of Time – Glenn Gould 7 ON! Stage Series 30 Chinese New Year Celebration 8 Club RHCPA 31 Dance Into the Light – the Best of Phil Collins 9 Series Packages 32 Dear Rouge 10 Dan Hill 33 Remembering Stuart 11 MAGIC! 34 Geronimo Stilton: Mouse in Space 12 Classic Albums LIVE: The Eagles - 35 Holly Cole Greatest Hits 36 Classic Albums LIVE: Help! 13 Serena Ryder 37 Matthew Good 14 Charlotte’s Web 38 Gandini Juggling’s Sigma 15 Thank You For Being a Friend 39 Erth’s Prehistoric Aquarium Adventure 16 Jeremy Hotz 40 Just For Laughs Road Show 17 MOON Vs.