The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 69. Last

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 53. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 53. Last time, Sun Quan’s adviser Lu Su had brought Zhuge Liang to the Southlands to meet with his master in hopes of forming an alliance between Liu Bei and the Southlands to resist Cao Cao. But when Lu Su went to see Sun Quan, he found the other advisers all telling Sun Quan that Cao Cao was too strong and that it was in everyone’s best interest to surrender. Sun Quan was nonplussed by this, and while he was taking a bathroom break, Lu Su told him that while everyone else could surrender to Cao Cao, Sun Quan alone could not. “For the likes of me,” Lu Su said, “surrender means being sent back to my hometown. Eventually, I can work my way back into high office. But if you surrender, you would not be able to go home. Your rank would be no more than a marquis. You would have but one carriage, one horse, and a few servants. You would be no one’s lord. Everyone else was just trying to save themselves. You must not listen to them. It’s time to make a master plan for yourself.” Now, Lu Su’s analysis is pretty spot on if you think about it. Look at what happened when Cao Cao took over Jing Province. All the officials and officers who surrendered made out pretty well with nice ranks and titles. But their former lord, Liu Cong (2), met an ignoble end. Sun Quan himself had just been pressed by his own advisers to surrender, and those advisers were no doubt looking out for themselves. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 32. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 32. Last time, Yuan Shao had mobilized his forces to attack Cao Cao, who responded by leading an army to meet Yuan Shao’s vanguard at the city of Baima (2,3). However, Cao Cao’s operation ran into a roadblock by the name of Yan Liang, Yuan Shao’s top general who easily slayed two of Cao Cao’s lesser officers. Feeling the need for a little more firepower, Cao Cao sent a messenger to the capital to summon Guan Yu. When Guan Yu received the order, he went to inform his two sisters-in-law, who reminded him to try to find some news about Liu Bei on this trip. Guan Yu then took his leave, grabbed his green dragon saber, hopped on his Red Hare horse, and led a few riders to Baima to see Cao Cao. “Yan Liang killed two of my officers and his valor is hard to match,” Cao Cao said. “That’s why I have invited you here to discuss how to deal with him.” “Allow me to observe him first,” Guan Yu said. Cao Cao had just laid out some wine to welcome Guan Yu when word came that Yan Liang was challenging for combat. So Guan Yu and Cao Cao went to the top of the hill to observe their enemy. Cao Cao and Guan Yu both sat down, while all the other officers stood. In front of them, at the bottom of the hill, Yan Liang’s army lined up in an impressive and disciplined formation, with fresh and brilliant banners and countless spears. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 73

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 73. Before we pick up where we left off, I should note that the show just celebrated its second anniversary a couple days ago. The introduction episode was published on April 9, 2014, and the first actual episode went up exactly two years ago today. Thank you to everyone who has listened to the podcast, rated it in iTunes, recommended it to a friend, and made a donation to support it. You guys have made this a great ride, and I’m looking forward to the next two years. So last time, after numerous unsuccessful attempts, Cao Cao finally managed to build a fortified camp on the Wei (4) River against Ma Chao, thanks to some freezing weather that allowed him to build a dirtandice wall. This done, he went out to taunt his enemy about it. Ma Chao did not take kindly to this and was just about to charge at Cao Cao when he noticed an imposing figure behind Cao Cao. Ma Chao suspected that this might be Xu Chu, the socalled Mad Tiger he had heard about. So he pointed with his whip and asked, “I have heard that your army has a Tiger Lord. Where is he?” “I AM Xu Chu!” the man behind Cao Cao shouted. Supernatural light seemed to shoot from his eyes, and his air was so imposing that Ma Chao dared not make a move against Cao Cao. Instead, he simply turned his horse around and returned to camp. -

The Congregation of Heroes: a Skyrim Representation

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 4-2017 The onC gregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation Richard Smith DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Richard, "The onC gregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation" (2017). Student research. 77. http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Congregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation Richard Smith Honor Scholar Program Senior Project 2017 Sponsor: Dr. Dave Berque First Reader: Dr. Sherry Mou Second Reader: Dr. Harry Brown 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 A Brief History 4 The Congregation of Heroes 6 Thesis Project 8 Skyrim and the Creation Kit 9 The Creation Process 10 Creative Decisions for the First Iteration 14 Technical Details for the First Iteration 18 The User Study 20 The Second Iteration 23 The Ethics of Translation 26 Conclusion 28 Acknowledgements 30 Works Cited 31 2 3 A Brief History The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is a novel detailing the events during the final years of the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. This time period, approximately 169 AD to 280 AD (Luo), was notable for the constant power struggles between the three kingdoms in China at the time. -

Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Cao Cao Dossier 曹操 Crisis Director: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Email: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Harjot Singh Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: 1. Front Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier (Pages 3-4) 4. Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5. Cao Zhang (Pages 7-8) 6. Cao Zhi (Pages 9-10) 7. Lady Bian (Page 11) 8. Emperor Xian of Han (Pages 12-13) 9. Empress Fu Shou (Pages 14-15) 10. Cao Ren (Pages 16-17) 11. Cao Hong (Pages 18-19) 12. Xun Yu (Pages 20-21) 13. Sima Yi (Pages 22-23) 14. Zhang Liao (Pages 24-25) 15. Xiahou Yuan (Pages 26-27) 16. Xiahou Dun (Pages 28-29) 17. Yue Jin (Pages 30-31) 18. Dong Zhao (Pages 32-33) 19. Xu Huang (Pages 34-35) 20. Cheng Yu (Pages 36-37) 21. Cai Yan (Page 38) 22. Han Ji (Pages 39-40) 23. Su Ze (Pages 41-42) 24. Works Cited (Pages 43-) Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier: Most characters within the Court of Cao Cao are either generals, strategists, administrators, or family members. ● Generals lead troops on the battlefield by both developing successful battlefield tactics and using their martial prowess with skills including swordsmanship and archery to duel opposing generals and officers in single combat. They also manage their armies- comprising of troops infantrymen who fight on foot, cavalrymen who fight on horseback, charioteers who fight using horse-drawn chariots, artillerymen who use long-ranged artillery, and sailors and marines who fight using wooden ships- through actions such as recruitment, collection of food and supplies, and training exercises to ensure that their soldiers are well-trained, well-fed, well-armed, and well-supplied. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 52

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 52. Previously, we left off with one of the most memorable sequences in the novel, in which Zhao Yun rescued Liu Bei’s infant son, A Dou (1,3), and fought his way through swarms of Cao Cao’s troops to escape. But no sooner had he left the bulk of Cao Cao’s army behind did he run into two more detachments of enemy soldiers, led by two lieutenants under the command of Cao Cao’s general Xiahou Dun. These two guys were brothers. One wielded a battle axe, while the other used a halberd, and they were shouting for Zhao Yun to surrender. Zhao Yun, of course, paid no heed to their words and greeted them with his spear. Within three bouts, the elder brother, the axe-wielder, was stabbed off his horse. Zhao Yun took the opening and ran. The younger brother, however, gave chase. As he closed in, the tip of his halberd flashed around Zhao Yun’s back. But Zhao Yun suddenly turned around, and the two were face to face right next to each other. Wielding his spear in his left hand, Zhao Yun blocked the halberd. At the same time, his right hand pulled out the prized sword that he had taken from Cao Cao’s sword-bearer earlier in the day. Where the sword landed, half of his opponent’s head and helmet went flying off. Seeing their leaders killed, the enemy soldiers scattered, and Zhao Yun once again fled toward Changban (2,3) Bridge. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 28. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 28. Last time, Liu Bei had convinced Cao Cao to let his take an army and go intercept Yuan Shu, who was on his way to join up with Yuan Shao. But soon after Liu Bei left the capital Xuchang, Cao Cao regretted his decision and sent his general Xu (2) Chu (3) to ask Liu Bei to turn around. When Xu Chu caught up, Liu Bei told him thanks but no thanks. A commander in the field doesn’t have to follow an order from his lord, so what are you going to do about it, aside from turning around and going home? Well, Xu Chu, who was not exactly the brightest light bulb on Cao Cao’s staff, thought to himself, “The prime minister has always been on good terms with Liu Bei. Besides, he didn’t order me to come start a fight. I’ll just relay his message and figure it out from there.” So Xu Chu took his leave and went back to tell Cao Cao what happened. When Cao Cao heard the report, he couldn’t decide how to proceed. His advisers Cheng Yu and Guo Jia, however, were sure this was a sign that Liu Bei has turned on him. “I have my officers Zhu (1) Ling (2) and Lu (4) Zhao (1) with him, so Liu Bei might not dare to turn on me,” Cao Cao said. “Besides, I have already issued the order; I cannot take it back.” And so he decided to let Liu Bei go. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure -

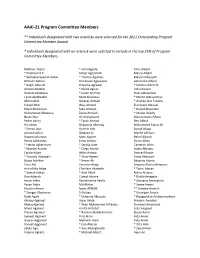

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members ** Individuals designated with two asterisks were selected for the 2021 Outstanding Program Committee Member Award. * Individuals designated with an asterisk were selected to include in the top 25% of Program Committee Members. Mathieu ’Aquin * John Agosta Chris Alberti * Prathosh A P Forest Agostinelli Marco Alberti * Sathyanarayanan Aakur * Thomas Agotnes Marjan Albooyeh Mohsen Abbasi Don Joven Agravante Alexandre Albore * Ralph Abboud Priyanka Agrawal * Stefano Albrecht Ahmed Abdelali * Derek Aguiar Vidal Alcazar Ibrahim Abdelaziz * Julien Ah-Pine Huib Aldewereld Tarek Abdelzaher Ranit Aharonov * Martin Aleksandrov Afshin Abdi Sheeraz Ahmad * Andrea Aler Tubella S Asad Abdi Wasi Ahmad Francesco Alesiani Majid Abdolshah Saba Ahmadi * Daniel Alexander Mohammad Abdulaziz Zahra Ahmadi * Modar Alfadly Naoki Abe Ali Ahmadvand Gianvincenzo Alfano Pedro Abreu * Faruk Ahmed Ron Alford Rui Abreu Shqiponja Ahmetaj Mohammed Eunus Ali * Erman Acar Hyemin Ahn Daniel Aliaga Avinash Achar Qingyao Ai Malihe Alikhani Rupam Acharyya Marc Aiguier Rahaf Aljundi Panos Achlioptas Esma Aimeur Oznur Alkan * Hanno Ackermann * Sandip Aine Cameron Allen * Maribel Acosta * Diego Aineto Adam Allevato Carole Adam Akiko Aizawa Amine Allouah * Sravanti Addepalli * Nirav Ajmeri Faisal Almutairi Bijaya Adhikari * Kenan Ak Eduardo Alonso Yossi Adi Yasunori Akagi Amparo Alonso-Betanzos Aniruddha Adiga Charilaos Akasiadis * Tansu Alpcan * Somak Aditya * Alan Akbik Mario Alviano Don Adjeroh Cuneyt Akcora * Daichi Amagata Aaron Adler Ramakrishna -

Study on the Relationship Between Guan Yu and Sun Quan (The Kingdom of Wu)

2019 International Conference on Cultural Studies, Tourism and Social Sciences (CSTSS 2019) Study on the Relationship between Guan Yu and Sun Quan (The Kingdom of Wu) Xinzhao Tang School of History and Culture, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China Keywords: Guan Yu; Sun Quan and the kingdom of Wu; Jingzhou Abstract: The alliance formation of Sun Quan and Liu Bei makes China's political structure gradually enter the “three kingdoms” era in the late Eastern Han Dynasty. After the battle of Red Cliff, the alliance gradually breaks down. Many scholars pass the buck to Guan Yu. They think that the reason why the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei broke down at last is because Guan Yu was too headstrong and he didn’t pay much attention to better the relationship with Sun Quan. This paper discusses the breakdown of the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei from Guan Yu's point of view. 1. Introduction The formation of the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei is the result of the change of the political pattern since the late Eastern Han Dynasty. The powerful warlords destroyed the weak warlords, and the weak warlords had to form an alliance to fight against the powerful warlords for their survival. As Cao Cao and his army were marching toward the south, Sun Quan and Liu Bei formed an alliance and defeated Cao Cao in the battle of Red Cliff. After that, with the threat of Cao Cao gradually decreasing, the contradiction between the two forces began to become increasingly sharp. -

C 2013 by Lu Su. All Rights Reserved. RESOURCE EFFICIENT INFORMATION INTEGRATION in CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS

c 2013 by Lu Su. All rights reserved. RESOURCE EFFICIENT INFORMATION INTEGRATION IN CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEMS BY LU SU DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Tarek F. Abdelzaher, Chair & Director of Research Professor Jiawei Han Professor Klara Nahrstedt Associate Professor Xue Liu, McGill University Abstract The proliferation of increasingly capable and affordable sensing devices that pervade every corner of the world has given rise to the fast development and wide deployment of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS). Hosting a whole spectrum of civilian and military applications, cyber-physical systems have fundamentally changed people's ways of everyday living, working, and interactions with the physical world in general. Despite their tremendous benefits, cyber-physical systems pose great new research challenges, of which, this thesis targets on one important facet, that is, to understand and optimize the tradeoff between the quality of information (QoI) provided by the sensor nodes and the consumption of system resources. On one hand, individual sensors are not reliable, due to various possible reasons including incomplete observations, environment and circuit board noise, poor sensor quality, lack of sensor calibration, or even intent to deceive. To address this sensor reliability problem, one common approach is to integrate information from multiple sensors that observe the same events, as this will likely cancel out the errors of individual sensors and improve the quality of information. On the other hand, cyber-physical systems usually have limited resources (e.g., energy, bandwidth, storage, time, space, money, devices or even the human labor). -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc.