Italian Egyptologists Through the Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary Notices

OBITUARY NOTICES SIR GASTON MASPEEO, K.C.M.G. WE regret to record the death, on June 30 last year, of our distinguished Honorary Member, Sir Gaston Maspero, who had long been regarded as the foremost Egyptologist of his generation. Among students of Egyptian antiquity he was the last of the great scholars who were able to include within the range of their activity the various branches of inquiry which tend more and more to become subjects of specialized study. In any survey of his career one is most struck by this extraordinary versatility. To most people his name will be familiar as that of one of the few great historians of the ancient world, his Histoire ancienne des peuples de I'Orient classique (which also appeared m an English form) surveying the ancient history of Egypt and Western Asia in the light of modern excavation and research. By Egyptian philologists he will always be remembered as the first editor and tems- lator of the " Pyramid Texts ", the earlier form assumed by those magical compositions for the benefit of the dead which were known by the Egyptians themselves as the " Chapters of Coming Forth by Day " and are conveniently referred to by modern writers as the " Book of the Dead ". He wrote much on art, mythology, and religion, and every- thing he published bore the impress of his keen insight and attractive style. As editor of the Recueil de travaux and as Director of the Egyptian Service des Antiquites he exerted a wide influence on others' work. In the latter capacity he came into close relations with British official life in Egypt, and his success in this difficult administrative post won him the English title he was proud to bear. -

On the Orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor. Philica, Philica, 2018. hal-01700520 HAL Id: hal-01700520 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01700520 Submitted on 4 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna (Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino) Abstract The Avenue of Sphinxes is a 2.8 kilometres long Avenue linking Luxor and Karnak temples. This avenue was the processional road of the Opet Festival from the Karnak temple to the Luxor temple and the Nile. For this Avenue, some astronomical orientations had been proposed. After the examination of them, we consider also an orientation according to a geometrical planning of the site, where the Avenue is the diagonal of a square, a sort of best-fit straight line in a landscape constrained by the presence of temples, precincts and other processional avenues. The direction of the rising of Vega was probably used as reference direction for the surveying. -

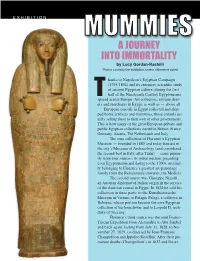

A Journey Into Immortality,” Which Opened on July 17 and Runs Until February 2, 2020

E X H I B I T I O N MUAM JOUMRNEY IES INTO IMMORTALITY by Lucy Gordan-Rastelli Photos courtesy the exhibition, unless ottherwise noted hanks to Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign (1798-1801) and its extensive scientific stud y of ancient Egyptian culture, during the first half of the Nineteenth Century Egyptomania spread across Europe. Art collectors, antique deal - Ters and merchants in Egypt, as well as — above all — European consuls in Egypt collected and ship- ped home artifacts and mummies, those consuls us- ually selling these to their own or other governments. This is how many of the great European private and public Egyptian collections started in Britain, France, Germany, Austria, The Netherlands and Italy . The core collection of Florence’s Egyptian Museum — founded in 1885 and today housed in the city’s Museum of Archaeology (and considered the second-best in Italy, after Turin) — came primar- ily from four sources, its initial nucleus preceding even Egyptomania and dating to the 1700s, original- ly be longing to Florence’s greatest art-patronage family from the Renaissance onwards, the Medicis. The second source was Giuseppe Nizzoli, an Austrian diplomat of Italian origin in the service of the Austrian consul in Egypt. In 1824 he sold his collection in three parts: to the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna; to Pelagio Palagi, a collector in Bologna, whose portion became the core Egyptian collection of his hometown; and to Leopold II, arch- duke of Tuscany. Florence’s third source was the joint Franco- Tuscan Expedition from Alexandria to Abu Simbel and back again, lasting from July 31, 1828, to No - vember 27, 1829, co-directed by Jean-Fran çois Champollion and Ippolito Rosellini. -

Nr. 31/1, 2011

31/1 31. 31. J UNI 2 0 1 1 ÅRGANG PAPYRUS Æ GYPTOLOGISK T IDSSKRIFT Indhold PAPYRUS 31. årgang nr. 1 2011 ENGLISH ABSTRACTS The triads of Mycerinos Johnny Barth Everyone interested in ancient Egypt is familiar with at least one of the triads of Mycerinos. Superb works of art, some in mint condition – but questions about them remain to be asked, in particular as to their original number and significance. The author assesses the evidence. Late 18th dynasty harems Lise Manniche The Amarna correspondence reveals exciting aspects of the rhetoric among sovereigns in the Near East in the late 18th dynasty, and it also provides a unique insight into human resources in the institution of an Egyptian harem. Pictorial and other evidence, however disjointed, adds to our understanding of its significance which was not solely aimed at the sexual gratification of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt. Mummy bandages in Danish Collections Thomas Christiansen A much neglected source of copies of chapters of the Book of the Dead is to be found on mummy bandages from the very end of the pharaonic period to the first Haremsbeboer: kvinde ved navn Tia, “amme” for prinsesse Ankhesenpaaten. century AD. For technical and other reasons their artistic qualities do not compete with those on papyrus, Blok fra Aten-templet i Amarna, nu i Metropolitan Museum of Art, New but they are nevertheless of interest as a niche medium York (foto LM). for conveying a message important to Egyptians at the time. The author presents examples from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, the National Museum and the Carlsberg Papyrus Collection in Copenhagen. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY PERCEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT THROUGH HISTORY, ACQUISITION, USE, DISPLAY, IMAGERY, AND SCIENCE OF MUMMIES ANNA SHAMORY SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Archaeological Science and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies with honors in Archaeological Science Reviewed and approved* by the following: Claire Milner Associate Research Professor of Anthropology Thesis Supervisor Douglas Bird Associate Professor of Anthropology Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT To the general public, ancient Egypt is the land of pharaohs, pyramids, and most importantly – mummies. In ancient times, mummies were created for a religious purpose. The ancient Egyptians believed that their bodies needed to be preserved after physical death, so they could continue into the afterlife. In the centuries after ancient Egypt fell to Roman control, knowledge about ancient Egyptian religion, language, and culture dwindled. When Egypt and its mummies were rediscovered during the Middle Ages, Europeans had little understanding of this ancient culture beyond Classical and Biblical sources. Their lack of understanding led to the use of mummies for purposes beyond their original religious context. After Champollion deciphered hieroglyphics in the 19th century, the world slowly began to learn about Egypt through ancient Egyptian writings in tombs, monuments, and artifacts. Fascination with mummies has led them to be one of the main sources through which people conceptualize ancient Egypt. Through popular media, the public has come to have certain inferences about ancient Egypt that differ from their original meaning in Pharaonic times. -

Paola Davoli

Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History Paola Davoli I. Introduction: the cultural and legal context of the first discoveries. The evaluation and publication of papyri and ostraka often does not take account of the fact that these are archaeological objects. In fact, this notion tends to become of secondary importance compared to that of the text written on the papyrus, so much so that at times the questions of the document’s provenance and find context are not asked. The majority of publications of Greek papyri do not demonstrate any interest in archaeology, while the entire effort and study focus on deciphering, translating, and commenting on the text. Papyri and ostraka, principally in Greek, Latin, and Demotic, are considered the most interesting and important discoveries from Greco-Roman Egypt, since they transmit primary texts, both documentary and literary, which inform us about economic, social, and religious life in the period between the 4th century BCE and the 7th century CE. It is, therefore, clear why papyri are considered “objects” of special value, yet not archaeological objects to study within the sphere of their find context. This total decontextualization of papyri was a common practice until a few years ago though most modern papyrologists have by now fortunately realized how serious this methodological error is for their studies.[1] Collections of papyri composed of a few dozen or of thousands of pieces are held throughout Europe and in the United States. These were created principally between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, a period in which thousands of papyri were sold in the antiquarian market in Cairo.[2] Greek papyri were acquired only sporadically and in fewer numbers until the first great lot of papyri arrived in Cairo around 1877. -

MUSEOLOGY and EGYPTIAN MATERIAL CULTURE MUSEO EGIZIO, TURIN (ITALY) Course ID: ARCH 365AD June 23 ‒ July 29, 2018 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTOR: Dr

MUSEOLOGY AND EGYPTIAN MATERIAL CULTURE MUSEO EGIZIO, TURIN (ITALY) Course ID: ARCH 365AD June 23 ‒ July 29, 2018 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTOR: Dr. Hans Barnard, MD PhD, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION The collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts kept in the Museo Egizio in Turin (Piedmont, Italy) is among the most important in the world. In 1824, King Charles Felix (1765‒1831) of the House of Savoy—that was ruling Savoy, Piedmont, Aosta and Sardinia from Turin at the time—acquired the collection accumulated by Bernardino Drovetti (1776‒1852), the French consul to Egypt. Once in Turin it was housed in a large building in the center of town where it resides until today. The collection was expanded with the purchase of more than 1200 objects gathered by Giuseppe Sossio, in 1833, and the more than 35,000 objects excavated and purchased by Ernesto Schiaparelli (1856‒1928) between 1900 and 1920. In the 1960s, the Nubian Temple of Ellesiya was presented by the Egyptian to the Italian government—to recognize their assistance during the UNESCO campaign to save the Nubian monuments—and rebuilt in the Museo Egizio. Next to this temple, important constituents of the collection include the Old Kingdom Tomb of the Unknown, the New Kingdom Tomb of Kha and Merit, several complete copies of the Book of the Dead, the Turin List of Kings, and the Turin Papyrus Map. The Fondazione Museo delle Antichità Egizie was established in 2004 as the result of an innovative configuration blending private and public funding, which is an experiment in museum management in Italy. -

Ucla Archaeology Field School

MUSEOLOGY AND EGYPTIAN MATERIAL CULTURE MUSEO EGIZIO, TURIN (ITALY) Course ID: ARCH 365AD SESSION I: June 16 ‒ July 21, 2019 SESSION II: July 28 ‒ September 1, 2019 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTORS: Dr. Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod, Department of Classical, Near Eastern and Religious Studies, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada ([email protected]) Dr. Hans Barnard, MD PhD, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION The collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts kept in the Museo Egizio in Turin (Piedmont, Italy) is among the most important in the world. In 1824, King Charles Felix (1765‒1831) of the House of Savoy—that was ruling Savoy, Piedmont, Aosta and Sardinia from Turin at the time—acquired the collection accumulated by Bernardino Drovetti (1776‒1852), the French consul to Egypt. Once in Turin it was housed in a large building in the center of town where it resides until today. The collection was expanded in 1833, with the purchase of more than 1200 objects gathered by Giuseppe Sossio, and again between 1900 and 1920 with more than 35,000 objects excavated and purchased by Ernesto Schiaparelli (1856‒1928). In the 1960s, the Nubian Temple of Ellesiya was presented by the Egyptian to the Italian government—to recognize their assistance during the UNESCO campaign to save the Nubian monuments—and rebuilt in the Museo Egizio. Next to this temple, important constituents of the collection include the Old Kingdom Tomb of the Unknown, the New Kingdom Tomb of Kha and Merit, several complete copies of the Book of the Dead, the Turin List of Kings, and the Turin Papyrus Map. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

Jean Francois Champollion the Father of Egyptology by John Warren Anyone Who Has Studied Ancient Egypt Will Be Familiar with Jean Francois Champollion

Jean Francois Champollion The Father of Egyptology by John Warren Anyone who has studied ancient Egypt will be familiar with Jean Francois Champollion. He was, after all, credited with deciphering hieroglyphics from the Rosetta Stone and thus giving scholars the key to understanding hieroglyphics. For this effort along, he is frequently referred to as the Father of Egyptology, for he provided the foundation that scholars would need in order to truly understand the ancient Egyptians. Even though he suffered a stroke, dying at the age of forty-one, he himself added to our knowledge of this grand, ancient civilization by translating any number of Egyptian texts prior to his death. Champollion was born on December 23rd, 1790 in the town of Figeac, France to Jacques Champollion and Jeanne Francoise. He was their youngest son, and was educated originally by his elder brother, Jacques Joseph (1778-1867). While still at home, he attempted to teach himself a number of languages, including Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean and Chinese. In 1801, at the age of ten, he was sent off to study at the Lyceum in Grenoble. There, at the young age of sixteen, he red a paper before the Grenoble Academy proposing that the language of the Coptic Christians in contemporary Egypt was actually the same language spoken PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com language to be at least an evolutionary form of the language spoken in the pharaonic period, spiked with the tongues of its foreign invaders such as the Greeks. His studies continued at the College de France between 1807 and 1809, where he specialized in Oriental languages. -

Interview with Barry John Kemp THIRTY FIVE YEARS of INVESTIGATION in ANCIENT AKHETATEN

DIGITAL MAGAZINE DI EGITTOLOGIA.NET / MEDITERRANEOANTICO.IT Interview with Barry John Kemp THIRTY FIVE YEARS OF INVESTIGATION IN ANCIENT AKHETATEN INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS NAUNTON IL VILLAGGIO OPERAIO DI DEIR EL-MEDINA L'organizzazione del lavoro: le serve e i servi LA MISSIONE ARCHEOLOGICA ITALO-RUSSA AD ABU ERTEILA LIVING HERITAGE: MANAGING SITES WITH HERITAGE “Rehabilitation of al Sakakini’s Palace” LA PAX AUGUSTA SUI RILIEVI DELL’ARA PACIS BOLLETTINO INFORMATIVO DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE EGITTOLOGIA.NET • ANNO 2015 • NUMERO 3 1 PaoloBondielli EDITORIALE RUMORI DI GUERRA Trovarsi a scrivere un editoriale con le immagini e le notizie di un mondo ferito dalla guerra, non è una cosa facile. La banalizzazione delle emo- zioni che spinge repentinamente a schierarsi da una parte o dall’altra, come se avessimo a disposizione ogni informazione necessaria per po- ter emettere il nostro oracolo, l’ho sempre trovata deleteria e superficia- le, oltre che inutile. Un po’ come valutare l’ultimo schiaffo che viene dato senza sapere come si è sviluppata l’intera rissa. Le contraddizioni si sprecano e gli ossimori si rincorrono in un vorticoso susseguirsi di eventi che fanno paura e sconvolgono il nostro quotidiano e quieto vivere, le nostre abitudini, le nostre certezze. Mi ha colpito molto in questi giorni la reazione composta dei francesi, il richiamo alla solidarietà fatto dalle loro istituzioni e il desiderio di rimane- re un Paese solidale, aperto, libero; valori che sono parte integrante del loro essere Nazione e che proprio per questo il terrorismo ha probabil- mente preso di mira. Mi ha invece scosso l’odio profondo che ho colto in molte dichiarazioni di “non francesi”, che hanno da subito individuato un nemico preciso e vorrebbero eliminarlo dalla faccia della terra senza nessuna riflessione, senza nessun desiderio di capire: l’islam. -

Documentation in Cairo's Museums and Its Impact on Collections

Documentation History in the Egyptian Museum Cairo and its impact on Collections Management content 1- The history of Egyptian Museum Cairo 2- Documentation history of Egyptian Museum Cairo 3- Documentation impact on collections management. 4- Defects of EMC documentation system 1- The Egyptian Museum Cairo is one of the oldest museums among Egypt's museums. The first idea for building this museum dates back to the reign of the ruler to Egypt Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1835. when he issued a decree contained three articles as follows; Article1 describes ''what is an antiquity thing?'', Article 2, is for collecting old things in a certain place (Ezbekiyya museum), and Article 3 is for prohibiting the export of antiquity things to outside Egypt Egyptian museum Cairo Buildings Boulaq Museum1863 Giza Museum1891 Egyptian museum Cairo As for the Current Egyptian Museum, was opened in 1902, and now is considered one of the largest museums all over world contains ancient Egyptian antiquities telling the history of ancient Egyptians' lives. It contains more than one hundred sixty thousand object are on display, besides the thousands else are in the basement and upper floor magazines. Those objects are representing different periods from the lithic periods to Greco-Roman via Pharaonic periods Egyptian Museum contains 7 sections as follows; Section 1: The antiquities of Jewelry, Tutankhamun, and Royal Mummies objects . Section 2: The antiquities of Prehistoric Periods through Old Kingdom. Section 3: The antiquities of Middle Kingdom Section 4: The antiquities of New Kingdom Section 5: The antiquities of Third Intermediate Periods through Greco-Roman Section 6-C: Coins, Section 6-P: Papyri Section 7: Ostraca, Coffins, and Scarabs 2- Documentation history of the Egyptian Museum Cairo: The actual history for scientific documentation in Egyptian Museum Cairo dates back when Auguste Mariette (1858- 1881) was appointed as a director of Egyptian Antiquities service and Egyptian museum in1858.