Rhinopithecus Roxellana) Living in Multi-Level Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonhuman Primates

Zoological Studies 42(1): 93-105 (2003) Dental Variation among Asian Colobines (Nonhuman Primates): Phylogenetic Similarities or Functional Correspondence? Ruliang Pan1,2,* and Charles Oxnard1 1School of Anatomy and Human Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Perth, WA 6009, Australia 2Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100080, China (Accepted August 27, 2002) Ruliang Pan and Charles Oxnard (2003) Dental variation among Asian colobines (nonhuman primates): phy- logenetic similarities or functional correspondence? Zoological Studies 42(1): 93-105. In order to reveal varia- tions among Asian colobines and to test whether the resemblance in dental structure among them is mainly associated with similarities in phylogeny or functional adaptation, teeth of 184 specimens from 15 Asian colobine species were measured and studied by performing bivariate (allometry) and multivariate (principal components) analyses. Results indicate that each tooth shows a significant close relationship with body size. Low negative and positive allometric scales for incisors and molars (M2s and M3s), respectively, are each con- sidered to be related to special dental modifications for folivorous preference of colobines. Sexual dimorphism in canine eruption reported by Harvati (2000) is further considered to be associated with differences in growth trajectories (allometric pattern) between the 2 sexes. The relationships among the 6 genera of Asian colobines found greatly differ from those proposed in other studies. Four groups were detected: 1) Rhinopithecus, 2) Semnopithecus, 3) Trachypithecus, and 4) Nasalis, Pygathrix, and Presbytis. These separations were mainly determined by differences in molar structure. Molar sizes of the former 2 groups are larger than those of the latter 2 groups. -

Title SOS : Save Our Swamps for Peat's Sake Author(S) Hon, Jason Citation

Title SOS : save our swamps for peat's sake Author(s) Hon, Jason SANSAI : An Environmental Journal for the Global Citation Community (2011), 5: 51-65 Issue Date 2011-04-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/143608 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University SOS: save our swamps for peatʼs sake JASON HON Abstract The Malaysian governmentʼs scheme for the agricultural intensification of oil palm production is putting increasing pressure on lowland areas dominated by peat swamp forests.This paper focuses on the peat swamp forests of Sarawak, home to 64 per cent of the peat swamp forests in Malaysia and earmarked under the Malaysian governmentʼs Third National Agriculture Policy (1998-2010) for the development and intensification of the oil palm industry.Sarawakʼs tropical peat swamp forests form a unique ecosystem, where rare plant and animal species, such as the alan tree and the red-banded langur, can be found.They also play a vital role in maintaining the carbon balance, storing up to 10 times more carbon per hectare than other tropical forests. Draining these forests for agricultural purposes endangers the unique species of flora and fauna that live in them and increases the likelihood of uncontrollable peat fires, which emit lethal smoke that can pose a huge environmental risk to the health of humans and wildlife.This paper calls for a radical reassessment of current agricultural policies by the Malaysian government and highlights the need for concerted effort to protect the fragile ecosystems of Sarawakʼs endangered -

The Role of Exposure in Conservation

Behavioral Application in Wildlife Photography: Developing a Foundation in Ecological and Behavioral Characteristics of the Zanzibar Red Colobus Monkey (Procolobus kirkii) as it Applies to the Development Exhibition Photography Matthew Jorgensen April 29, 2009 SIT: Zanzibar – Coastal Ecology and Natural Resource Management Spring 2009 Advisor: Kim Howell – UDSM Academic Director: Helen Peeks Table of Contents Acknowledgements – 3 Abstract – 4 Introduction – 4-15 • 4 - The Role of Exposure in Conservation • 5 - The Zanzibar Red Colobus (Piliocolobus kirkii) as a Conservation Symbol • 6 - Colobine Physiology and Natural History • 8 - Colobine Behavior • 8 - Physical Display (Visual Communication) • 11 - Vocal Communication • 13 - Olfactory and Tactile Communication • 14 - The Importance of Behavioral Knowledge Study Area - 15 Methodology - 15 Results - 16 Discussion – 17-30 • 17 - Success of the Exhibition • 18 - Individual Image Assessment • 28 - Final Exhibition Assessment • 29 - Behavioral Foundation and Photography Conclusion - 30 Evaluation - 31 Bibliography - 32 Appendices - 33 2 To all those who helped me along the way, I am forever in your debt. To Helen Peeks and Said Hamad Omar for a semester of advice, and for trying to make my dreams possible (despite the insurmountable odds). Ali Ali Mwinyi, for making my planning at Jozani as simple as possible, I thank you. I would like to thank Bi Ashura, for getting me settled at Jozani and ensuring my comfort during studies. Finally, I am thankful to the rangers and staff of Jozani for welcoming me into the park, for their encouragement and support of my project. To Kim Howell, for agreeing to support a project outside his area of expertise, I am eternally grateful. -

A Note on Responses of Juvenile Javan Lutungs (Trachypithecus Auratus Mauritius) Against Attempted Predation by Crested Goshawks (Accipter Trivirgatus)

人と自然 Humans and Nature 25: 105−110 (2014) Report A note on responses of juvenile Javan lutungs (Trachypithecus auratus mauritius) against attempted predation by crested goshawks (Accipter trivirgatus) Yamato TSUJI 1*, Hiroyoshi HIGUCHI 2 and Bambang SURYOBROTO 3 1 Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Inuyama, Japan 2 Graduate School of Media and Governance, Keio University, Fujisawa, Japan 3 Bogor Agricultural University, Java West, Indonesia Abstract On October 31st, 2013, we unexpectedly observed attempted predation of two juvenile Javan lutungs (Trachypithecus auratus mauritius) by adult crested goshawks (Accipter trivirgatus), in Pangandaran Nature Reserve, West Java, Indonesia. The goshawks flew over a group of feeding lutungs, attempting attacks only on juvenile lutungs from the rear, while emitting tweeting calls. The attacks involved two different birds (probably a pair) in turn from different directions. The attacks by the goshawks were repeated six times during our observation period (between 13:51 and 13:58), but none of the attempts was successful. During the attacks, no other lutungs in the group showed any anti-predator behavior (such as emitting alarm calls or escaping) against the goshawks perhaps because their body weight (6-10 kg) was much larger than that of goshawk (0.4-0.6 kg). To our knowledge, this is the first detailed report of hunting-related behavior to primates by this raptor species. Key words: Accipter trivirgatus, crested goshawk, Javan lutung, Pangandaran, predation, Trachypithecus auratus mauritius Introduction primates has been conducted for over 50 years. However, with the exception of Philippine eagles Predation is considered to be a principal selective (Pithecophaga jefferyi) and hawk-eagles (Spizaetus force leading to the evolution of behavioral traits spp.), reports on the predation of primates by raptors and social systems in primates (van Schaik, 1983; in Asia are limited (Ferguson-Lee and Christie, 2001; Hart, 2007), although there are few case studies on Hart, 2007; Fam and Nijman, 2011). -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Mitochondrial and Nuclear Markers Suggest Hanuman Langur (Primates: Colobinae) Polyphyly: Implications for Their Species Status

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54 (2010) 627–633 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Mitochondrial and nuclear markers suggest Hanuman langur (Primates: Colobinae) polyphyly: Implications for their species status K. Praveen Karanth a,c,*, Lalji Singh b, Caro-Beth Stewart c a Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, India b Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500007, India c Department of Biological Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY 12222, USA article info abstract Article history: Recent molecular studies on langurs of the Indian subcontinent suggest that the widely-distributed and Received 30 June 2008 morphologically variable Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus) are polyphyletic with respect to Revised 9 October 2009 Nilgiri and purple-faced langurs. To further investigate this scenario, we have analyzed additional Accepted 29 October 2009 sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome b as well as nuclear protamine P1 genes from these species. Available online 6 November 2009 The results confirm Hanuman langur polyphyly in the mitochondrial tree and the nuclear markers sug- gest that the Hanuman langurs share protamine P1 alleles with Nilgiri and purple-faced langurs. We rec- Keywords: ommend provisional splitting of the so-called Hanuman langurs into three species such that the Semnopithecus taxonomy is consistent with -

Habitat Suitability of Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis Larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 11, November 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 5155-5163 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d211121 Habitat suitability of Proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia TRI ATMOKO1,2,♥, ANI MARDIASTUTI3♥♥, M. BISMARK4, LILIK BUDI PRASETYO3, ♥♥♥, ENTANG ISKANDAR5, ♥♥♥♥ 1Research and Development Institute for Natural Resources Conservation Technology. Jl. Soekarno-Hatta Km 38, Samboja, Samarinda 75271, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-542-7217663, Fax.: +62-542-7217665, ♥email: [email protected], [email protected]. 2Program of Primatology, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lodaya II No. 5, Bogor 16151, West Java, Indonesia 3Department of Forest Resource Conservation and Ecotourism, Faculty of Forestry and Environment, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lingkar Akademik, Kampus IPB Dramaga, Bogor16680, West Java, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-251-8621677, ♥♥email: [email protected], ♥♥♥[email protected] 4Forest Research and Development Center. Jl. Gunung Batu No 5, Bogor 16118, West Java, Indonesia 5Primate Research Center, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Jl. Lodaya II No. 5, Bogor 16151, West Java, Indonesia. Tel./fax.: +62-251-8320417, ♥♥♥♥email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 1 October 2020. Revision accepted: 13 October 2020. Abstract. Atmoko T, Mardiastuti A, Bismark M, Prasetyo LB, Iskandar E. 2020. Habitat suitability of Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 21: 5155-5163. Habitat suitability of Proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) in Berau Delta, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. The proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is an endemic species to Borneo's island and is largely confined to mangrove, riverine, and swamp forests. Most of their habitat is outside the conservation due to degraded and habitat converted. -

Nilgiri Langur: Biology and Status 1 2

National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii) May, 2011 National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii) Studbook compiled and analysed by Manjari Malviya Anupam Srivastav Parag Nigam P. C. Tyagi May, 2011 Copyright © WII, Dehradun and CZA, New Delhi, 2011 Cover Photo: Dr. H.N. Kumara This report may be quoted freely but the source must be acknowledged and cited as: Malviya. M., Srivastav, A., Nigam. P, and Tyagi. P.C., 2011. Indian National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii). Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. Published as Technical Report of the CZA assignment for compilation and publication of Indian National Studbooks for selected endangered species of wild animals in Indian zoos. Acknowledgements This studbook is a part of the Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi, assignment to the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun for the compilation and publication of studbooks of selected endangered faunal types in Indian zoos. The authors wish to thank the Central Zoo Authority for financial support and the opportunity to compile the National Studbook for Nilgiri Langur. We are thankful to Shri. P. R. Sinha, Director, WII for his guidance and support. We would also like to express our appreciation for the advice and support extended by Dr. V. B. Mathur, Dean Faculty of Wildlife Sciences, WII. The authors also wish to thank Shri. B.S. Bonal, Member Secretary, CZA, Dr. B.K. Gupta, Evaluation and monitoring officer, Dr. Naeem Akhtar, Scientific Officer and Mr. Vivek Goel, Data Processing Assistant, CZA for their kind support. The help of the following zoos holding Nilgiri langur in captivity in India is gratefully acknowledged in compilation of data for the studbook. -

Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus Guereza in Kakamega Forest, Ke

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 28, No. 3, June 2007 (C 2007) DOI: 10.1007/s10764-006-9096-2 Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus guereza in Kakamega Forest, Kenya Peter J. Fashing,1,2,3,7 Ellen S. Dierenfeld,4,5 and Christopher B. Mowry6 Received February 22, 2006; accepted May 26, 2006; Published Online May 24, 2007 Nutritional factors are among the most important influences on primate food choice. We examined the influence of macronutrients, minerals, and sec- ondary compounds on leaf choices by members of a foli-frugivorous popula- tion of eastern black-and-white colobus—or guerezas (Colobus guereza)— inhabiting the Kakamega Forest, Kenya. Macronutrients exerted a complex influence on guereza leaf choice at Kakamega. At a broad level, protein con- tent was the primary factor determining whether or not guerezas consumed specific leaf items, with eaten leaves at or above a protein threshold of ca. 14% dry matter. However, a finer grade analysis considering the selection ra- tios of only items eaten revealed that fiber played a much greater role than protein in influencing the rates at which different items were eaten relative to their abundance in the forest. Most minerals did not appear to influence leaf choice, though guerezas did exhibit strong selectivity for leaves rich in zinc. Guerezas avoided most leaves high in secondary compounds, though their top food item (Prunus africana mature leaves) contained some of the high- est condensed tannin concentrations of any leaves in their diet. Kakamega 1Department of Science and Conservation, Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium, One Wild Place, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15206. -

Olive Colobus (Procolobus Verus) Call Combinations and Ecological

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ISSN 2320-7078 Olive colobus (Procolobus verus) call combinations and JEZS 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ecological parameters in Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire © 2013 AkiNik Publications Received 24-10-2013 Accepted: 07-11-2013 Jean-Claude Koffi BENE, Eloi Anderson BITTY, Kouame Antoine Jean-Claude Koffi BENE N’GUESSAN UFR Environnement, Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé; BP 150 Abstract Daloa Animal communication is any transfer of information on the part of one or more animals that has an Email: [email protected] effect on the current or future behavior of another animal. The ability to communicate effectively with other individuals plays a critical role in the lives of all animals and uses several signals. Eloi Anderson BITTY Acoustic communication is exceedingly abundant in nature, likely because sound can be adapted to a Centre Suisse de Recherches wide variety of environmental conditions and behavioral situations. Olive colobus monkeys produce Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP a finite number of acoustically distinct calls as part of a species-specific vocal repertoire. The call 1303 Abidjan 01 system of Olive colobus is structurally more complex because calls are assembled into higher-order Email: [email protected] level of sequences that carry specific meanings. Focal animal studies and Ad Libitum conducted in three groups of Olive colobus monkeys in Taï National Park indicate that some environmental and Kouame Antoine N’GUESSAN social parameters significantly affect the emission of different call combination types of this monkey Centre Suisse de Recherches species. Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP 1303 Abidjan 01 Email: [email protected] Keywords: Olive colobus, call combination, social parameter, environment parameter. -

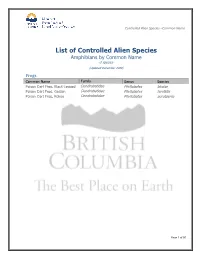

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

AFRICAN PRIMATES the Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group

Volume 9 2014 ISSN 1093-8966 AFRICAN PRIMATES The Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group Editor-in-Chief: Janette Wallis PSG Chairman: Russell A. Mittermeier PSG Deputy Chair: Anthony B. Rylands Red List Authorities: Sanjay Molur, Christoph Schwitzer, and Liz Williamson African Primates The Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group ISSN 1093-8966 African Primates Editorial Board IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Janette Wallis – Editor-in-Chief Chairman: Russell A. Mittermeier Deputy Chair: Anthony B. Rylands University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK USA Simon Bearder Vice Chair, Section on Great Apes:Liz Williamson Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK Vice-Chair, Section on Small Apes: Benjamin M. Rawson R. Patrick Boundja Regional Vice-Chairs – Neotropics Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo; Univ of Mass, USA Mesoamerica: Liliana Cortés-Ortiz Thomas M. Butynski Andean Countries: Erwin Palacios and Eckhard W. Heymann Sustainability Centre Eastern Africa, Nanyuki, Kenya Brazil and the Guianas: M. Cecília M. Kierulff, Fabiano Rodrigues Phillip Cronje de Melo, and Maurício Talebi Jane Goodall Institute, Mpumalanga, South Africa Regional Vice Chairs – Africa Edem A. Eniang W. Scott McGraw, David N. M. Mbora, and Janette Wallis Biodiversity Preservation Center, Calabar, Nigeria Colin Groves Regional Vice Chairs – Madagascar Christoph Schwitzer and Jonah Ratsimbazafy Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Michael A. Huffman Regional Vice Chairs – Asia Kyoto University, Inuyama,