The Role of Exposure in Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity and Ranging Patterns of Guerezas in the Kakamega Forest: Intergroup Variation and Implications for Intragroup Feeding Competition

P1: Vendor International Journal of Primatology [ijop] PP095-296772 June 6, 2001 11:50 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2001 Activity and Ranging Patterns of Guerezas in the Kakamega Forest: Intergroup Variation and Implications for Intragroup Feeding Competition Peter J. Fashing1,2 Received November 29, 1999; revision July 13, 2000; accepted August 10, 2000 From March 1997 to February 1998, I investigated the activity patterns of 2 groups and the ranging patterns of 5 groups of eastern black-and-white colobus (Colobus guereza), aka guerezas, in the Kakamega Forest, Kenya. Guerezas at Kakamega spent more of their time resting than any other pop- ulation of colobine monkeys studied to date. In addition, I recorded not one instance of intragroup aggression in 16,710 activity scan samples, providing preliminary evidence that intragroup contest competition may be rare or ab- sent among guerezas at Kakamega. Mean daily path lengths ranged from 450 to 734 m, and home range area ranged from 12 to 20 ha, though home range area may have been underestimated for several of the study groups. Home range overlap was extensive with 49–83% of each group’s range overlapped by the ranges of other groups. Despite the high level of home range overlap, the frequently entered areas (quadrats entered on 30% of a group’s total study days) of any one group were not frequently entered by any other study group. Mean daily path length is not significantly correlated with levels of availability or consumption of any plant part item. -

Habitat Utilization and Feeding Biology of Himalayan Grey Langur

动 物 学 研 究 2010,Apr. 31(2):177−188 CN 53-1040/Q ISSN 0254-5853 Zoological Research DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1141.2010.02177 Habitat Utilization and Feeding Biology of Himalayan Grey Langur (Semnopithecus entellus ajex) in Machiara National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan Riaz Aziz Minhas1,*, Khawaja Basharat Ahmed2, Muhammad Siddique Awan2, Naeem Iftikhar Dar3 (1. World Wide Fund for Nature-Pakistan (WWF-Pakistan) AJK Office Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir 13100, Pakistan; 2. Department ofZoology, University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir 13100, Pakistan; 3. Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Government of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir 13100, Pakistan) Abstract: Habitat utilization and feeding biology of Himalayan Grey Langur (Semnopithecus entellus ajex) were studied from April, 2006 to April, 2007 in Machiara National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. The results showed that in the winter season the most preferred habitat of the langurs was the moist temperate coniferous forests interspersed with deciduous trees, while in the summer season they preferred to migrate into the subalpine scrub forests at higher altitudes. Langurs were folivorous in feeding habit, recorded as consuming more than 49 plant species (27 in summer and 22 in winter) in the study area. The mature leaves (36.12%) were preferred over the young leaves (27.27%) while other food components comprised of fruits (17.00%), roots (9.45%), barks (6.69%), flowers (2.19%) and stems (1.28%) of various plant species. Key words: Himalayan Grey Langur; Habitat; Food biology; Machiara National Park 喜马拉雅灰叶猴栖息地利用和食性生物学 Riaz Aziz Minhas1,*, Khawaja Basharat Ahmed2, Muhammad Siddique Awan2, Naeem Iftikhar Dar3 (1. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Gastrointestinal Parasites of the Colobus Monkeys of Uganda

J. Parasitol., 91(3), 2005, pp. 569±573 q American Society of Parasitologists 2005 GASTROINTESTINAL PARASITES OF THE COLOBUS MONKEYS OF UGANDA Thomas R. Gillespie*², Ellis C. Greiner³, and Colin A. Chapman²§ Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: From August 1997 to July 2003, we collected 2,103 fecal samples from free-ranging individuals of the 3 colobus monkey species of UgandaÐthe endangered red colobus (Piliocolobus tephrosceles), the eastern black-and-white colobus (Co- lobus guereza), and the Angolan black-and-white colobus (C. angolensis)Ðto identify and determine the prevalence of gastro- intestinal parasites. Helminth eggs, larvae, and protozoan cysts were isolated by sodium nitrate ¯otation and fecal sedimentation. Coprocultures facilitated identi®cation of helminths. Seven nematodes (Strongyloides fulleborni, S. stercoralis, Oesophagostomum sp., an unidenti®ed strongyle, Trichuris sp., Ascaris sp., and Colobenterobius sp.), 1 cestode (Bertiella sp.), 1 trematode (Dicro- coeliidae), and 3 protozoans (Entamoeba coli, E. histolytica, and Giardia lamblia) were detected. Seasonal patterns of infection were not apparent for any parasite species infecting colobus monkeys. Prevalence of S. fulleborni was higher in adult male compared to adult female red colobus, but prevalence did not differ for any other shared parasite species between age and sex classes. Colobinae is a large subfamily of leaf-eating, Old World 19 from Angolan black-and-white colobus. Red colobus are sexually monkeys represented in Africa by species of 3 genera, Colobus, dimorphic, with males averaging 10.5 kg and females 7.0 kg (Oates et al., 1994); they display a multimale±multifemale social structure and Procolobus, and Piliocolobus (Grubb et al., 2002). -

Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus Guereza in Kakamega Forest, Ke

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 28, No. 3, June 2007 (C 2007) DOI: 10.1007/s10764-006-9096-2 Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus guereza in Kakamega Forest, Kenya Peter J. Fashing,1,2,3,7 Ellen S. Dierenfeld,4,5 and Christopher B. Mowry6 Received February 22, 2006; accepted May 26, 2006; Published Online May 24, 2007 Nutritional factors are among the most important influences on primate food choice. We examined the influence of macronutrients, minerals, and sec- ondary compounds on leaf choices by members of a foli-frugivorous popula- tion of eastern black-and-white colobus—or guerezas (Colobus guereza)— inhabiting the Kakamega Forest, Kenya. Macronutrients exerted a complex influence on guereza leaf choice at Kakamega. At a broad level, protein con- tent was the primary factor determining whether or not guerezas consumed specific leaf items, with eaten leaves at or above a protein threshold of ca. 14% dry matter. However, a finer grade analysis considering the selection ra- tios of only items eaten revealed that fiber played a much greater role than protein in influencing the rates at which different items were eaten relative to their abundance in the forest. Most minerals did not appear to influence leaf choice, though guerezas did exhibit strong selectivity for leaves rich in zinc. Guerezas avoided most leaves high in secondary compounds, though their top food item (Prunus africana mature leaves) contained some of the high- est condensed tannin concentrations of any leaves in their diet. Kakamega 1Department of Science and Conservation, Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium, One Wild Place, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15206. -

Bioko Red Colobus Piliocolobus Pennantii Pennantii (Waterhouse, 1838) Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (2004, 2006, 2010, 2012)

Bioko Red Colobus Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii (Waterhouse, 1838) Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (2004, 2006, 2010, 2012) Drew T. Cronin, Gail W. Hearn & John F. Oates Bioko red colobus (Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii) (Illustration: Stephen D. Nash) Pennant’s red colobus monkey Piliocolobus pennantii is P. p. pennantii is threatened by bushmeat hunting, presently regarded by the IUCN Red List as comprising most notably since the early 1980s when a commercial three subspecies: P. pennantii pennantii of Bioko, P. p. bushmeat market appeared in the town of Malabo epieni of the Niger Delta, and P. p. bouvieri of the Congo (Butynski and Koster 1994). Following the discovery Republic. Some accounts give full species status to of offshore oil in 1996, and the subsequent expansion all three of these monkeys (Groves 2007; Oates 2011; of Equatorial Guinea’s economy, rising urban demand Groves and Ting 2013). P. p. pennantii is currently led to increased numbers of primate carcasses in the classified as Endangered (Oates and Struhsaker 2008). bushmeat market (Morra et al. 2009; Cronin 2013). In November 2007, a primate hunting ban was enacted Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii may once have occurred on Bioko, but it lacked any realistic enforcement and over most of Bioko, but it is now probably limited to an contributed to a spike in the numbers of monkeys in the area of less than 300 km² within the Gran Caldera and market. Between October 1997 and September 2010, a 510 km² range in the Southern Highlands Scientific a total of 1,754 P. p. pennantii were observed for sale Reserve (GCSH) (Cronin et al. -

Olive Colobus (Procolobus Verus) Call Combinations and Ecological

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ISSN 2320-7078 Olive colobus (Procolobus verus) call combinations and JEZS 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ecological parameters in Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire © 2013 AkiNik Publications Received 24-10-2013 Accepted: 07-11-2013 Jean-Claude Koffi BENE, Eloi Anderson BITTY, Kouame Antoine Jean-Claude Koffi BENE N’GUESSAN UFR Environnement, Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé; BP 150 Abstract Daloa Animal communication is any transfer of information on the part of one or more animals that has an Email: [email protected] effect on the current or future behavior of another animal. The ability to communicate effectively with other individuals plays a critical role in the lives of all animals and uses several signals. Eloi Anderson BITTY Acoustic communication is exceedingly abundant in nature, likely because sound can be adapted to a Centre Suisse de Recherches wide variety of environmental conditions and behavioral situations. Olive colobus monkeys produce Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP a finite number of acoustically distinct calls as part of a species-specific vocal repertoire. The call 1303 Abidjan 01 system of Olive colobus is structurally more complex because calls are assembled into higher-order Email: [email protected] level of sequences that carry specific meanings. Focal animal studies and Ad Libitum conducted in three groups of Olive colobus monkeys in Taï National Park indicate that some environmental and Kouame Antoine N’GUESSAN social parameters significantly affect the emission of different call combination types of this monkey Centre Suisse de Recherches species. Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP 1303 Abidjan 01 Email: [email protected] Keywords: Olive colobus, call combination, social parameter, environment parameter. -

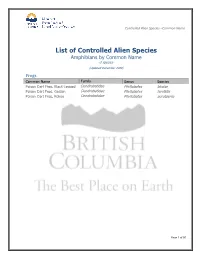

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

Piliocolobus Semlikiensis, Semliki Red Colobus

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2020: T92657343A92657454 Scope(s): Global Language: English Piliocolobus semlikiensis, Semliki Red Colobus Assessment by: Maisels, F. & Ting, N. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Maisels, F. & Ting, N. 2020. Piliocolobus semlikiensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T92657343A92657454. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020- 1.RLTS.T92657343A92657454.en Copyright: © 2020 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Primates Cercopithecidae Scientific Name: Piliocolobus semlikiensis (Colyn, 1991) Synonym(s): • Colobus ellioti Dollman, 1909 • Colobus variabilis Lorenz von Liburnau, 1914 • Colobus badius ssp. -

A Model of Colobus and Piliocolobus Behavioural Ecology: One Folivore

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 1 2 Time constraints limit group sizes and distribution in red and black-and- 3 white colobus monkeys 4 5 6 Amanda H. Korstjens 7 R.I.M. Dunbar 8 9 10 British Academy Centenary Research Project 11 School of Biological Sciences 12 University of Liverpool 13 Crown St 14 Liverpool L69 7ZB 15 England 16 17 18 Email: [email protected] 19 20 21 22 23 Short title: Colobine model 24 Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 25 ABSTRACT 26 Several studies have shown that, in frugivorous primates, a major constraint on group size is 27 within-group feeding competition. This relationship is less obvious in folivorous primates. 28 We investigated whether colobine group sizes are constrained by time limitations as a result 29 of their low energy diet and ruminant-like digestive system. We used climate as an easy to 30 obtain proxy for the productivity of a habitat. Using the relationships between climate, group 31 size and time budget components observed for Colobus and Piliocolobus populations at 32 different research sites, we created two taxon-specific models. In both genera, feeding time 33 increased with group size (or biomass). The models for Colobus and Piliocolobus correctly 34 predicted the presence or absence of the genus at, respectively, 86% of 148 and 84% of 156 35 African primate sites. Median predicted group sizes where the respective genera were present 36 were 19 for Colobus and 53 for Piliocolobus. -

Refuting the Validity of Golden-Crowned Langur Presbytis Johnaspinalli Nardelli 2015 (Mammalia, Primates, Cercopithecidae)

Zoosyst. Evol. 97 (1) 2021, 141–145 | DOI 10.3897/zse.97.62235 No longer based on photographs alone: refuting the validity of golden-crowned langur Presbytis johnaspinalli Nardelli 2015 (Mammalia, Primates, Cercopithecidae) Vincent Nijman1 1 Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, School of Social Sciences and Centre for Functional Genomics, Department of Biological and Medical Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Oxford, OX3 0BP, UK http://zoobank.org/2C3A7C82-A9BE-4FD1-A21D-113EC28C0224 Corresponding author: Vincent Nijman ([email protected]) Academic editor: M.T.R. Hawkins ♦ Received 18 December 2020 ♦ Accepted 19 January 2021 ♦ Published 11 February 2021 Abstract Increasingly, new species are being described without there being a name-bearing type specimen. In 2015, a new species of primate was described, the golden-crowned langur Presbytis johnaspinalli Nardelli, 2015 on the basis of five photographs that were posted on the Internet in 2009. After publication, the validity of the species was questioned as it was suggested that the animals were par- tially and selectively bleached ebony langurs Trachypithecus auratus (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812). Since the whereabouts of the animals were unknown, it was difficult to see how this matter could be resolved and the current taxonomic status of P. johnaspinalli remains unclear. I present new information about the fate of the individual animals in the photographs and their species identifica- tion. In 2009, thirteen of the langurs on which Nardelli based his description were brought to a rescue centre where, after about three months, they regained their normal black colouration confirming the bleaching hypothesis. Eight of the langurs were released in a forest and two were monitored for two months in 2014. -

Seasonal Variation in Diet and Nutrition of the Northern-Most Population of Rhinopithecus Roxellana

Received: 29 January 2018 | Revised: 19 February 2018 | Accepted: 6 March 2018 DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22755 RESEARCH ARTICLE Seasonal variation in diet and nutrition of the northern-most population of Rhinopithecus roxellana Rong Hou1 | Shujun He1 | Fan Wu1 | Colin A. Chapman1,2,3,4 | Ruliang Pan1,5 | Paul A. Garber6 | Songtao Guo1 | Baoguo Li1,7 1 Shaanxi Key Laboratory for Animal Conservation, College of Life Sciences, There is a great deal of spatial and temporal variation in the availability and nutritional ’ Northwest University, Xi an, China quality of foods eaten by animals, particularly in temperate regions where winter brings 2 Department of Anthropology and McGill School of Environment, McGill University, lengthy periods of leaf and fruit scarcity. We analyzed the availability, dietary Montreal, Quebec, Canada composition, and macronutrients of the foods eaten by the northern-most golden 3 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx, New snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) population in the Qinling Mountains, York China to understand food choice in a highly seasonal environment dominated by 4 Section of Social Systems Evolution, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Kyoto, deciduous trees. During the warm months between April and November, leaves are Japan consumed in proportion to their availability, while during the leaf-scarce months 5 School of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology, The University of Western Australia, between December and March, bark and leaf/flower buds comprise most of their diet. Perth, Australia When leaves dominated their diet, golden snub-nosed monkeys preferentially selected 6 Department of Anthropology, University leaves with higher ratios of crude protein to acid detergent fiber.