Paper for B(&N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simplified WWII Timeline

~ Belz Museum of Asian and Judaic Art ~ Holocaust Memorial Gallery ~ Simplified World War II Timeline 1933 JANUARY 30, 1933 German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler chancellor. At the time, Hitler was leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi party). FEBRUARY 27-28, 1933 The German parliament (Reichstag) building burned down under mysterious circumstances. The government treated it as an act of terrorism. FEBRUARY 28, 1933 Hitler convinced President von Hindenburg to invoke an emergency clause in the Weimar Constitution. The German parliament then passed the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of Nation (Volk) and State, popularly known as the Reichstag Fire Decree, the decree suspended the civil rights provisions in the existing German constitution, including freedom of speech, assembly, and press, and formed the basis for the incarceration of potential opponents of the Nazis without benefit of trial or judicial proceeding. MARCH 22, 1933 The SS (Schutzstaffel), Hitler's “elite guard,” established a concentration camp outside the town of Dachau, Germany, for political opponents of the regime. It was the only concentration camp to remain in operation from 1933 until 1945. By 1934, the SS had taken over administration of the entire Nazi concentration camp system. MARCH 23, 1933 The German parliament passed the Enabling Act, which empowered Hitler to establish a dictatorship in Germany. APRIL 1, 1933 The Nazis organized a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Germany. Many local boycotts continued throughout much of the 1930s. APRIL 7, 1933 The Nazi government passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which excluded Jews and political opponents from university and governmental positions. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’S Included

World War Two Tours Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’s included: Hotel Bed & Breakfast All transport from the official overseas start point Accompanied for the trip duration All Museum entrances All Expert Talks & Guidance Low Group Numbers “Amazing time, one of those ‘once in a life time trips’. WelI organised, very interesting and thoroughly enjoyable. I would recommend the trip to any enthusiast.” Operation Reinhard (German: Aktion Reinhard or Einsatz Reinhard) was the code name given to the Nazi plan to murder Polish Jews in the General Government, and marked the most deadly phase of the Holocaust, the use of extermination camps. During the operation, as many as two Military History Tours is all about the ‘experience’. Naturally we take million people were murdered in Bełżec, Sobibor and Treblinka, almost all of whom were Jews. care of all local accommodation, transport and entrances but what By 1942, the Nazis had decided to undertake the Final Solution. sets us aside is our on the ground knowledge and contacts, established This led to the establishment of camps such as Bełżec, over many, many years that enable you to really get under the surface of Sobibor and Treblinka which had the express purpose of killing your chosen subject matter. thousands of people quickly and efficiently. These sites differed By guiding guests around these from those such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek because historic locations we feel we are contributing greatly towards ‘keeping they also operated as forced-labour camps, these were purely the spirit alive’ of some of the most killing factories. The organizational apparatus behind the memorable events in human history. -

Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland

Miranda Walston Witnessing Extermination: Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland Honours Thesis By: Miranda Walston Supervisor: Dr. Lauren Rossi 1 Miranda Walston Introduction The Holocaust spanned multiple years and states, occurring in both German-occupied countries and those of their collaborators. But in no one state were the actions of the Holocaust felt more intensely than in Poland. It was in Poland that the Nazis constructed and ran their four death camps– Treblinka, Sobibor, Chelmno, and Belzec – and created combination camps that both concentrated people for labour, and exterminated them – Auschwitz and Majdanek.1 Chelmno was the first of the death camps, established in 1941, while Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec were created during Operation Reinhard in 1942.2 In Poland, the Nazis concentrated many of the Jews from countries they had conquered during the war. As the major killing centers of the “Final Solution” were located within Poland, when did people in Poland become aware of the level of death and destruction perpetrated by the Nazi regime? While scholars have attributed dates to the “Final Solution,” predominantly starting in 1942, when did the people of Poland notice the shift in the treatment of Jews from relocation towards physical elimination using gas chambers? Or did they remain unaware of such events? To answer these questions, I have researched the writings of various people who were in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” I am specifically addressing the information found in diaries and memoirs. Given language barriers, this thesis will focus only on diaries and memoirs that were written in English or later translated and published in English.3 This thesis addresses twenty diaries and memoirs from people who were living in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” Most of these diaries (fifteen of twenty) were written by members of the intelligentsia. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

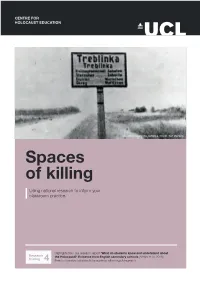

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

THE NAZI ANTI-URBAN UTOPIA Generalplan Ost

MONOGRAPH Mètode Science Studies Journal, 10 (2020): 165-171. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.10.13009 ISSN: 2174-3487. eISSN: 2174-9221. Submitted: 03/09/2018. Approved: 11/03/2019. THE NAZI ANTI-URBAN UTOPIA Generalplan Ost UNAI FERNÁNDEZ DE BETOÑO Nazi Germany saw Eastern Europe as an opportunity to expand its territory, its living space. Poland would become the laboratory for an inhumane colonisation plan, the Generalplan Ost (“General Plan for the East”), which involved replacement of the non-Aryan population with Germanic farmers. The anti-urban management of that lobotomised territory was scientifically drafted by a group of architects, geographers, and agronomists working under the orders of Heinrich Himmler. The urban planning aspects of this utopian plan, based on central place theory, self-sufficiency, and neighbourhood units, were of great technical interest and influenced the creation of new communities within Franco’s regime. However, we cannot overlook the fact that, had the Nazi plan been completed, it would have resulted in the forced relocation of 31 million Europeans. Keywords: Nazi Germany, Generalplan Ost, land management, colonisation, urban planning. ■ INTRODUCTION for the colonisation of the Eastern territories, mainly the land occupied in Poland between 1939 and 1945. The fields of urban planning and land management The Nazi colonisation of Poland, both in territories have historically focused on significantly different annexed by the Third Reich and those in the objectives depending on the authors of each plan and Generalgouvernement, was a testing ground for land when they were created. Some have given greater management and was understood as a scientific and prominence to the artistic components of urban technical discipline. -

4. General Government Expenditures

III. PUBLIC FINANCE AND ECONOMICS 4. General government expenditures Governments spend money to provide goods and services differences between countries. Between 2000 and 2009, the and redistribute income. Like government revenues, largest increases in government expenditures per person government expenditures reflect historical and current were recorded in Korea, Estonia and Ireland (over 6%) while political decisions but are also highly sensitive to economic in Austria, Italy, Japan and Switzerland the increases were developments. General government spending as a share of equal to or below 1%; and in Israel there was no change. GDP and per person provide an indication of the size of the government across countries. However, the large variation in these ratios highlights different approaches to delivering public goods and services and providing social protection, not necessarily differences in resources spent. For instance, Methodology and definitions if support is given via tax breaks rather than direct Government expenditures data are derived from the expenditures, expenditure/GDP ratios will naturally be OECD National Accounts Statistics, which are based on lower. In addition, it is important to note that the size of the System of National Accounts (SNA), a set of inter- expenditures does not reflect government efficiency or nationally agreed concepts, definitions, classifica- productivity. tions and rules for national accounting. In SNA Government expenditures represented 46% of GDP across terminology, general government consists of central, OECD member countries in 2009. In general, OECD-EU state and local governments and social security member countries have a higher ratio than other OECD funds. member countries. Denmark, Finland and France spend Gross domestic product (GDP) is the standard the most as a share of GDP, with government expenditures measure of the value of the goods and services equal to or above 56%, whereas Mexico, Chile, Korea and produced by a country during a period. -

The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom Through German-Jewish Eyes

Chapter 4 The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom through German-Jewish Eyes Alan E. Steinweis The November 1938 pogrom, often referred to as the “Kristallnacht,” was the largest and most significant instance of organized anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany before the Second World War.1 In addition to the massive destruc- tion of synagogues and property, the pogrom involved the physical abuse and terrorizing of German Jews on a massive scale. German police reported an official death toll of 91, but the actual number of Jews killed was probably about ten times that many when one includes fatalities among Jews who were treated brutally during their arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.2 Violence had been a normal feature of the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish measures since 1933,3 but the scale and intensity of the Kristallnacht were unprecedented. The pogrom occurred less than one year before the outbreak of the war and the first atrocities by the Wehrmacht against Polish Jews, and less than three years before the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, and other units began to undertake the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union. Knowledge about the perpetrators of the pogrom, therefore, pro- vides important context for understanding the violence that came later. To be sure, nobody has yet undertaken the extremely ambitious project to identify precisely which perpetrators of the Kristallnacht eventually would participate directly in the “Final Solution.” There certainly were many such cases, however, perhaps the most notable being Odilo Globocnik, who presided over the po- grom violence in Vienna in November 1938 and less than three years later was placed in charge of Operation Reinhardt, the mass murder of the Jews in the General Government.4 1 Many of the observations in this chapter are based on cases described and documented in the author’s book, Kristallnacht 1938 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). -

Krakow HISTORY

Krakow HISTORY The first documented reference to Krakow can be found in records from 965 of the Cordova merchant Abraham ben Jacob. He mentions a rich burg city situated at the crossing of trade routes and surrounded by woods. In the 10th century Mieszko I incorporated Krakow into the Polish state. During the times of Boleslaw the Brave, the bishopric of Krakow was established (1000) and the construction of Wawel Cathedral began. In 1038, Casimir I the Restorer made Wawel Castle its seat, thus making Krakow the capital of Poland. The high duke Boleslav V the Chaste following the example of Wrocław, introduced city rights modelled on the Magdeburg law allowing for tax benefits and new trade privileges for the citizens in 1257. In the 15th century, Krakow became the center of lively cultural, artistic, and scientific development. Photo: A fragment of colourful woodcut depicting Krakow. Source: https://www.muzeumkrakowa.pl The 17th and 18th centuries were a period of a gradual decline of the city's importance. Due to the first partition of Poland in 1772, the southern part of Little Poland was seized by the Austrian army. On March 24, 1794 Kościuszko's Insurrection began in Krakow. Temporarily included into the Warsaw Duchy, it was given the status of a "free city" after Napoleon's downfall. After the defeat of the November Insurrection (1831), Krakow preserved its autonomy as the only intact part of Poland. In 1846, it was absorbed into the Austrian Monarchy again. After independence was regained in 1918, Krakow became a significant administrative and cultural center. -

Poles Under German Occupation the Situation and Attitudes of Poles During the German Occupation

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/poles-under-german-occu/15596,Poles-under-German-Occupation.html 2021-09-25, 22:48 Poles under German Occupation The Situation and Attitudes of Poles during the German Occupation The Polish population found itself in a very difficult situation during the very first days of the war, both in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in The General Government. The policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Executions, resettlements, arrests, deportations to camps, and street round-ups were a constant element of the everyday life of Poles during the war. Initially the policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Food rationing was imposed in cities and towns, with food coupons covering about one-third of a person’s daily needs. Levies — obligatory, regular deliveries of selected produce — were introduced in the countryside. Farmers who failed to deliver their levy were subject to severe repressions, including the death penalty. Devaluation and difficulty with finding employment were the reason for most Poles’ poverty and for the everyday problems in obtaining basic products. The occupier also limited access to healthcare. The birthrate fell dramatically while the incidence of infectious diseases increased significantly. -

Holocaust Myths and Misconceptions

Holocaust Myths and Misconceptions 1. German Jews were a large proportion of Germany’s population. a. In 1933, approximately 9.5 million Jews lived in Europe, comprising 1.7% of the total European population. This number represented more than 60 percent of the world’s Jewish population at that time, estimated at 15.3 million. Of these, the largest Jewish community was in Poland – about 3,250,000 Jews or 9.8% of the Polish population. Germany’s approximately 565,000 Jews made up only 0.8% of its population. 2. Killing Jews was on Hitler and the Nazi Party’s agenda from the beginning. a. Plans to murder Europe’s Jews began when forced immigration out of German territory was no longer a viable goal. In part because German territory kept expanding into areas that contained millions of Jews. The authorization for the “Final Solution” began in July 1941 and was finally ratified in January 1942. 3. The Nazis system of concentration camps consisted of about 10,000 camps. a. From 1933-1945 over 44,000 camps existed across occupied Europe. 4. Most concentration camps had a gas chamber and crematoria. a. Only six camps were designated as systematic killing centers. Camps equipped with gassing facilities, for mass murder of Jews included Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, and Treblinka. Industrial scale crematoria only existed at Auschwitz-Birkenau and only after 1943. Up to 2,700,000 Jews were murdered at these camps, as were tens of thousands of Gypsies, Soviet prisoners of war, Poles, and others. 5. All Jews in camps received tattoo numbers on their arms.