Moray in March 1915 - As Reported in the Northern Scot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Engineers Journal

---------.---- The Royal Engineers , I' * .ii ; Journal. H'lii I '' ) Sir Charles Pasley (IV) . Lieut.-Colonel P. ealy 569 1 Mechanization and Divisional Engineers. Part m. f' Brevet Lieut.-Colonel N. T. Fitzratrick 691 A Subaltern in the Indian Mutiny. Part VI. Brevet Colonel C. B. Thackeray 597 Repairs to the Barge Pier at Shoeburyness . Brevet Major A. Winnis 611 i Further Notes on the Roorkee Pattern Steel Crib Lieut.-Colonel G. Le Q. Martel 687 The Principles of Combined Operations . Brigadier W. G. S. Dobbie 640 The Transatlantic Venture . Captain W. G. Fryer 656 Further Experiments in Vibro-Concrete Piling in the North-West Frontier Province Colonel C. H. Haswell 677 The Principles and Practice of Lubrication as Applied to Motor Vehicles Captain S. G. Galpin 685 Two Sapper Subalterns in Tibet . Lieutenant L. T. Grove 690 Bridging on the Chitral Road, with Special Reference to the N.W.R. Portable Type Steel Bridge . Lieutenant W. F. Anderson 702 Report on Concealment from the Air . Major B. C. Dening 706 An "F" Project . Lieutenant A. E. M. Walter 711 A Mining 8tory . V. 715 Memoirs. Books. Magazines. Correspondence . 716 VOL. XLV. DECEMBER, 1931. CHATHAM: THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. TELEPHONE: CHATHAM, 2669. AGENTS AND PRINTERS: MACKAYS LTD. LONDON: 171 HUGH RZES. LTD.. 5. REGENT STREET. S.W.I. ..... m; 11-. 4 J"b !" All ,:,i INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE , v.= L-. - ·--·11-1 EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL Specialities "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEET i REINFORCEMENT FOR I CONCRETE. "EXPAMET" and "BB" LATHINGS FOR PLASTERWORK. "EXMET" REINFORCEMENT FOR BRICKWORK. "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEETS, for Fencing, Openwork Partitions, Machinery Guards, Switchboard Enclosures, Etc. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships. -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

CALL the HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.13 October 2017

CALL THE HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.13 October 2017 From the President The Naval Historical Society of Australia (NHSA) has grown over more than four decades from a small Garden Island, Sydney centric society in 1970 to an Australia wide organization with Chapters in Victoria, WA and the ACT and an international presence through the website and social media. Having recently established a FACEBOOK presence with a growing number of followers. Society volunteers have been busy in recent months enhancing the Society’s website. The new website will be launched in December 2017 at our AGM. At the same time, we plan to convert Call the Hands into digital newsletter format in lieu of this PDF format. This will provide advantage for readers and the Society. The most significant benefit of NHSA membership of the Society is receipt of our quarterly magazine, the Naval Historical Review which is add free, up to fifty pages in length and includes 8 to 10 previously unpublished stories on a variety of historical and contemporary subjects. Stories greater than two years old are made available to the community through our website. The membership form is available on the website. If more information is required on either membership or volunteering for the Society, please give us a call or e-mail us. Activities by our regular band of willing volunteers in the Boatshed, continue to be diverse, interesting and satisfying but we need new helpers as the range of IT and web based activities grows. Many of these can be done remotely. Other activities range from routine mail outs to guiding dockyard tours, responding to research queries, researching and writing stories. -

Sugar-Coated Fortress: Representations of the Us Military in Hawai'!

SUGAR-COATED FORTRESS: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE U. S. MILITARY IN HAWAI'!. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEl\1BER 2004 By Brian Ireland Dissertation Committee: David Stannard, Chairperson Floyd Matson Robert Perkinson Kathy Ferguson Ira Rohter ABSTRACT Hawai'i is the most militarized state in the nation. There has always been opposition to the U.S. military presence in Hawai'i. However, critics ofthe military face a difficult task in getting their message across. Militarism has been so ingrained in Hawai'i that, to a large extent, the U.S. military presence has come to be seen as "natural," necessary, and almost totally beneficial. A result ofthis is that it has become both easy and comfortable to view current militarism in Hawai'i as natural, normal, ordinary, and expected. This dissertation shows how this seemingly normal state of affairs came to be. By examining various representations ofthe U.S. military in Hawai'i - in newspapers, movies, memorials, museums, and military writing - I expose how, in forms ofrepresentation, places ofremembrance, and the construction ofhow we speak and write about the military, militarism becomes the norm and, in turn, silences counter narratives. The dissertation examines four distinct time periods, 1778 to 1898 (from Captain Cook to the annexation ofHawai'i by the U.S.), 1898-1927 (the period in which the U.S. consolidated its hold on Hawai'i through cultural imperialism and military build-up), 1927-1969 (which saw the growth ofmass tourism, the Massie Case, the attack on Pearl Harbor, martial law and Statehood), and 1965-present (covering the post-Statehood years, the Vietnam War, increasing militarization ofHawai'i, the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement, and the Ehime Maru tragedy). -

Odhams' A.B.C. of the Great War

-/If) .. i!k,s/«».Vn'j . W-- '(ft , , I' .Oil. i:K .' ODHAMS' A.B.C. OF THE GREAT WAR =ol[S -o oo lo- -o o \r nl li| ODHAMS' ^r^ A.B.C. 3 OF THE GREAT WAR Compiled and Edited by E. W. GOLBROOK \2} London: ODHAMS LIMITED 39 King Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 2 ^ Jj Ito o- -o oo o- -o o To the Tuhlic '^^ 3LL that is claimed for this work is that it is a compilation of the various miscellaneous accounts, articles, etc., which have been issued from day to day, carefully collated from news- papers, text-books, biographies, geographies, etc., etc., set out in alphabetical order, which, it is hoped, will be found of service as a guide to the war and as a took of reference. !t has been my endeavour to put in very brief form everything that it is desirable to know relating to the war, and which one could have ascertained for oneself by perusing the various newspapers, books, etc. (not, however, always accessible), on the subject ; but / have done it for you, I have not gone into past history, but have merely stated how the war commenced, who is in it, and the dates when, and the places where, each event in the war took place after the commencement of it. Germany's lust for world power, its aims at world domination, its intention to crush France and Russia and then Britain, taking the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife as its excuse for committing its horrible atrocities, is left to others to expound in full. -

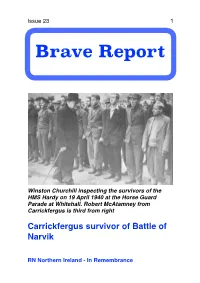

Brave Report Issue 23 NARVIK1/CARRICK

Issue 23 !1 Brave Report ! Winston Churchill inspecting the survivors of the HMS Hardy on 19 April 1940 at the Horse Guard Parade at Whitehall. Robert McAtamney from Carrickfergus is third from right Carrickfergus survivor of Battle of Narvik RN Northern Ireland - In Remembrance Issue 23 !2 ! HMS Hardy Robert McAtamney from Carrickfergus served in HMS Hardy at the first Battle of Narvik in April 1940. He survived ship wreck. With his fellow survivors, he met Winston Churchill and was recognised by a presentation in his home town. Robert, known as Bobby, was one of six boys from the same family who fought in the war. They became known as the fighting McAtamney’s as they represented the Army, Navy and Airforce. Although three of them were wounded, all came home safe after the war. Bobby, an Able Seaman at the time of the Battle of Narvik, was only twenty years old at the time. Bobby had a lucky escape when he was hit by RN Northern Ireland - In Remembrance Issue 23 !3 ! Tubby Cox taking the parade of survivors.Even after all that they had been through their humour was still high shrapnel. It took his top lip off but, it could just as easily been his head. He plunged in to the icy waters and as he swam ashore he noticed another ship mate Tubby’ Cox floating unconscious in the water and dragged him to safety. They had a laugh about it afterwards, as Bobby said that Tubby only floated because of his size. After the ship had blown up and he and the rest of the survivors were led to safety, he RN Northern Ireland - In Remembrance Issue 23 !4 was given a ski suit, and that’s what he wore to come home. -

The Standard History of the War Vol. IV

The Standard History of the War Vol. IV By Edgar Wallace The Standard History of the War CHAPTER I. — THE FIGHT OFF HELIGOLAND WAR was declared on August 4 at midnight (German time). At that moment the British fleet, mobilised and ready, was at the stations which had been decided upon in the event of war with Germany. By an act of foresight which cannot be too highly commended the fleet had been mobilised for battle practice a week or so before the actual outbreak of hostilities and at a time when it was not certain whether Great Britain would engage herself in the war. The wisdom of our preparations was seen after war was declared. From the moment the battle fleet sailed from Spithead and disappeared over the horizon it vanished so far as the average man in the street was concerned, and from that day onward its presence was no more advertised. The first few days following the outbreak of war we suffered certain losses. On August 6 the Amphionwas mined after having destroyed by gun fire the Königin Luise. On September 5 the Pathfinder was torpedoed by a "U" boat, and on September 22 the Aboukir, the Cressy, and the Hogue were destroyed by a German submarine. In the meantime the German had had his trouble. The Magdeburg was shot down by gun fire at the hands of the Russian navy. The Köln, the Ariadne and the Mainz with the German destroyer V187 had been caught in the Bight of Heligoland, and had been sunk. We had our lessons to learn, and we were prompt to profit by dire experience. -

Transcribed Diary of Leslie STORY 1914

+ A transcription of the wartime diaries and service records of Leslie John William Story covering the period from 20 October 1914 to 1 February 1918. © 1998 Compiled and edited by Ian L James Updated 27 August 2018 2 3 Leslie John William Story 8th June 1895 – 18th December 1963 4 5 Table of Contents An amazing coincidence ..................................................................................................................................................................8 Reference sources.............................................................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1 – "A Rough Passage" ..................................................................................................................................................12 October 1914 ....................................................................................................................................................................................14 Temuka Railway Station 1908 ..................................................................................................................................................14 NZR Q and A Class locomotives..................................................................................................................................................14 T. S. S. Wahine 1913 - 1951 ..................................................................................................................................................14 -

LA KAISERLICHE MARINE. ALEMANIA Y LA BÚSQUEDA DEL PODER MUNDIAL 1898-1914” Michael Epkenhans (Zentrum Für Militärgeschichte Und Sozialwissenschaften Der Bundeswehr)

“LA KAISERLICHE MARINE. ALEMANIA Y LA BÚSQUEDA DEL PODER MUNDIAL 1898-1914” Michael Epkenhans (Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr) BIBLIOGRAFÍA BÁSICA Berghahn, V. R. (1973): Germany and the approach of war in 1914. London: St. Martin’s Epkenhans, M. (2008): Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. Architect of the Geman Battle Fleet. Washington D.C.: Potomac Books. Herwig, H. (1987): “Luxury Fleet”. The Imperial German Navy 1888-1918. London: Ashfield Press. Seligman, M.; Epkenhans, M. et. al. (Eds.) (2014): The Naval Route to the Abyss. The Anglo-German Naval Race 1895-1914. London: Routledge. “LA ROYAL NAVY EN GUERRA” Andrew Lambert (King’s College London) BIBLIOGRAFÍA BÁSICA Corbett, J. (1920-1922): The Official History of Naval Operations. 3 vols. London: Longmans Green and Co. Fisher, J. A. (1920): Memories and Records. New York: George H. Doran Company. Mackay, R. (1969): Fisher of Kilverstone. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Marder, A. (1970-1971): From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Offer, A. (1989): The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wegener, W. (1989): The Sea Strategy of the World War. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. “EL HMS DREADNOUGHT Y LA EVOLUCIÓN DEL ARMA NAVAL” Tobias Philbin BIBLIOGRAFÍA BÁSICA Bennett, G. (1972): The Battle of Jutland. London: David and Charles Newton Abbot. Dodson, A. (2016): The Kaiser’s Battlefleet German Capital Ships 1871-1918. Barnsley: Seaforth Press. Friedman, N. (2011): Naval Weapons of World War One, Guns Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations an Illustrated Directory. Barnsley: Seaforth Press. Taylor, J. C. (1970): German Warships of World War I. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly

By Webmaster The FAAAA is honoured to be able to publish the following Thesis by Dr. Sharron Spargo, who prepared it as part of her Degree of Doctory of Philosophy in 2016. She advises me that the work is currently being rewritten in preparation for publication as a history of the Fleet Air Arm, in its own right. Any readers who have served in the RAN Fleet Air Arm will relate to this work: it traces the evolution of the FAA from the very early days though to the present, and in doing so delves into detail of the truly memorable post WWII parts of our history: the Korean Conflict and Vietnam in particular. But it is not a dry history, as some are. It contains the names and thoughts of many names that we recognise: ship and squadron mates who served with us, and whose insights into circumstances and events are of themselves great interest. I commend it to you as a body of work that serves to capture, from a fresh perspective, the life and times of this the very best Arm of the Royal Australian Navy. Our grateful thanks go to Dr Spargo for allowing this work to be published on our website. Marcus Peake Webmaster 10Jun17 We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. -

The Gallipolian Index

THE GALLIPOLIAN INDEX Note for guidance on using the Index 1. The index was originally compiled in 2007 by Gallipoli Association member, Robert Pike, to whom the then Editor, David Saunders and his successors are greatly indebted. The original index was updated and significantly expanded by Foster Summerson when he edited the journal from 2008 - 2015, and more recently by myself. 2. The index does not aim to be a comprehensive guide to everything that has appeared in The Gallipolian over the past years. It is essentially an alphabetical listing, by subject area, of articles dealing with a range of 'Gallipoli related' topics. 3. Items within each subject area (e.g. Merchant Navy, Suvla etc.) are listed with the issue number in which they appeared. Thus, for example, an article that featured in issue No. 69 will be listed before one on the same or similar subject that appeared in issue No. 86. The only exceptions are in the case of Book Reviews, Obituaries and Poetry (see paragraph 5 below). Where articles encompass different subject areas, every effort has been made to record the article in each (e.g. a memoir written by a veteran of the campaign, will be listed both under 'Memories/ Reflections'; the unit in which he served; and often under the veteran's name). 4. County regiments afforded the title ‘Royal’ are listed thus: Berkshire Regiment, Royal. Other regiments and corps afforded that honour (e.g. Royal Fusiliers, Royal Irish Rifles etc.) are indexed under ‘R’ – ‘Royal …’. 5. Book Reviews (listed alphabetically by author), Obituaries (alphabetically by name of the deceased and sub-divided between Veterans and others) and Poetry (alphabetically by title) are contained in separate sections at the end of the main index.