University College University of New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Navy Commodore Allan Du Toit Relieved Rear Adm

FESR Archive (www.fesrassociation.com) Documents appear as originally posted (i.e. unedited) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Visitors Log: Archived Messages: General: October to December 2007 The FESR Visitors Log http://fesrassociation.com/cgi-bin/yabb2/YaBB.pl General >> Bulletin Board >> RAN Commodore Takes Over CTF 158 http://fesrassociation.com/cgi-bin/yabb2/YaBB.pl?num=1191197194 st Message started by seashells on Oct 1 , 2007, 10:06am Title: RAN Commodore Takes Over CTF 158 Post by seashells on Oct 1st, 2007, 10:06am NSA, Bahrain -- Royal Australian Navy Commodore Allan du Toit relieved Rear Adm. Garry E. Hall as commander of Combined Task Force (CTF) 158 during a ceremony at Naval Support Activity Bahrain Sept. 27. Command of CTF 158 typically rotates among coalition partners Australia, United Kingdom and the United States. CTF 158 is comprised of coalition ships and its primary mission in the Persian Gulf is Maritime Security Operations (MSO) in and around both the Al Basrah and Khawr Al Amaya Oil Terminals (ABOT and KAAOT, respectively), in support of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1723. This resolution charges the multinational force with the responsibility and authority to maintain security and stability in Iraqi territorial waters and also supports the Iraqi government's request for security support. Additionally, under the training and leadership of CTF 158, Iraqi marines aboard ABOT and KAAOT train with the coalition in order to eventually assume responsibility for security. “I am honored to have been in command of this task force,” said Hall. “The coalition forces have done an excellent job of providing security to the oil platforms and training the Iraqi forces.” “I am very proud of the coalition forces and my staff in supporting the CTF 158 mission,” said Capt. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Westland Wessex

This article is taken from Wikipedia Westland Wessex This article is about the helicopter. For the fixed-wing for rapid starting and thus faster response times.[1] The aircraft, see Westland IV. Wessex could also operate in a wide range of weather conditions as well as at night, partly due to its use of an automatic pilot system. These same qualities that made The Westland Wessex is a British-built turbine-powered the Wessex well-suited to the anti-submarine role also development of the Sikorsky H-34, it was developed lent themselves to the search and rescue (SAR) mission, and produced under license by Westland Aircraft (later which the type would become heavily used for.[1] Westland Helicopters). One of the main changes from Sikorsky’s H-34 was the replacement of the piston-engine powerplant with a turboshaft engine; the Wessex was the first helicopter in the world to be produced in large num- bers that made use of a gas turbine propulsion system.[1] Early models were powered by a single Napier Gazelle engine, later builds used a pair of Rolls-Royce Gnome engines. The Wessex was initially produced for the Royal Navy (RN) and later for the Royal Air Force (RAF); a limited number of civilian aircraft were also produced, as well as some export sales. The Wessex operated as an anti- submarine warfare and utility helicopter; it is perhaps best recognised for its use as a search and rescue (SAR) he- licopter. The type entered operational service in 1961, A pair of Royal Navy Wessex helicopters in the flight deck of the and had a service life in excess of 40 years before being HMS Intrepid, 1968 retired in Britain. -

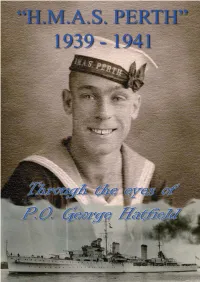

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Royal Engineers Journal

---------.---- The Royal Engineers , I' * .ii ; Journal. H'lii I '' ) Sir Charles Pasley (IV) . Lieut.-Colonel P. ealy 569 1 Mechanization and Divisional Engineers. Part m. f' Brevet Lieut.-Colonel N. T. Fitzratrick 691 A Subaltern in the Indian Mutiny. Part VI. Brevet Colonel C. B. Thackeray 597 Repairs to the Barge Pier at Shoeburyness . Brevet Major A. Winnis 611 i Further Notes on the Roorkee Pattern Steel Crib Lieut.-Colonel G. Le Q. Martel 687 The Principles of Combined Operations . Brigadier W. G. S. Dobbie 640 The Transatlantic Venture . Captain W. G. Fryer 656 Further Experiments in Vibro-Concrete Piling in the North-West Frontier Province Colonel C. H. Haswell 677 The Principles and Practice of Lubrication as Applied to Motor Vehicles Captain S. G. Galpin 685 Two Sapper Subalterns in Tibet . Lieutenant L. T. Grove 690 Bridging on the Chitral Road, with Special Reference to the N.W.R. Portable Type Steel Bridge . Lieutenant W. F. Anderson 702 Report on Concealment from the Air . Major B. C. Dening 706 An "F" Project . Lieutenant A. E. M. Walter 711 A Mining 8tory . V. 715 Memoirs. Books. Magazines. Correspondence . 716 VOL. XLV. DECEMBER, 1931. CHATHAM: THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. TELEPHONE: CHATHAM, 2669. AGENTS AND PRINTERS: MACKAYS LTD. LONDON: 171 HUGH RZES. LTD.. 5. REGENT STREET. S.W.I. ..... m; 11-. 4 J"b !" All ,:,i INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE , v.= L-. - ·--·11-1 EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL Specialities "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEET i REINFORCEMENT FOR I CONCRETE. "EXPAMET" and "BB" LATHINGS FOR PLASTERWORK. "EXMET" REINFORCEMENT FOR BRICKWORK. "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEETS, for Fencing, Openwork Partitions, Machinery Guards, Switchboard Enclosures, Etc. -

Australia's Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise

AUSTRALIA’S NAVAL SHIPBUILDING ENTERPRISE Preparing for the 21st Century JOHN BIRKLER JOHN F. SCHANK MARK V. ARENA EDWARD G. KEATING JOEL B. PREDD JAMES BLACK IRINA DANESCU DAN JENKINS JAMES G. KALLIMANI GORDON T. LEE ROGER LOUGH ROBERT MURPHY DAVID NICHOLLS GIACOMO PERSI PAOLI DEBORAH PEETZ BRIAN PERKINSON JERRY M. SOLLINGER SHANE TIERNEY OBAID YOUNOSSI C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1093 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9029-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Australian government will produce a new Defence White Paper in 2015 that will outline Australia’s strategic defense objectives and how those objectives will be achieved. -

FROM CRADLE to GRAVE? the Place of the Aircraft

FROM CRADLE TO GRAVE? The Place of the Aircraft Carrier in Australia's post-war Defence Force Subthesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES at the University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1996 by ALLAN DU TOIT ACADEMY LIBRARy UNSW AT ADFA 437104 HMAS Melbourne, 1973. Trackers are parked to port and Skyhawks to starboard Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Allan du Toit Canberra, October 1996 Ill Abstract This subthesis sets out to study the place of the aircraft carrier in Australia's post-war defence force. Few changes in naval warfare have been as all embracing as the role played by the aircraft carrier, which is, without doubt, the most impressive, and at the same time the most controversial, manifestation of sea power. From 1948 until 1983 the aircraft carrier formed a significant component of the Australian Defence Force and the place of an aircraft carrier in defence strategy and the force structure seemed relatively secure. Although cost, especially in comparison to, and in competition with, other major defence projects, was probably the major issue in the demise of the aircraft carrier and an organic fixed-wing naval air capability in the Australian Defence Force, cost alone can obscure the ftindamental reordering of Australia's defence posture and strategic thinking, which significantly contributed to the decision not to replace HMAS Melbourne. -

Cockatoo Island

EHA MAGAZINE Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine Volume 3 No.8 May 2021 Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine ISSN 2206-0200 (Online) May 2021 This is a free magazine covering stories and news items about Volume 3 Number 8 industrial and engineering heritage in Australia and elsewhere. EDITOR: It is published online as a down-loadable PDF document for Margret Doring, FIEAust. CPEng. M.ICOMOS readers to view on screen or print their own copies. EA members and non-members on the EHA mailing lists will receive emails The Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine is notifying them of new issues, with a link to the relevant Engineers published by Engineers Australia’s National Australia website page. Committee for Engineering Heritage. Statements made or opinions expressed in the Magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect CONTENTS the views of Engineers Australia. Editorial 3 Contact EHA by email at: In honour of Jack Mundey AO, 1929 – 2020 3 [email protected] or visit the website at: Recognising Wartime Service in Public Utilities 4 https://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/Communiti Cockatoo Island – Industrial Powerhouse 6 es-And-Groups/Special-Interest-Groups/Engineerin g-Heritage-Australia A Black Summer for Victoria's Bridges 15 Sydney's Earliest Public Water Supplies 20 Unsubscribe: If you do not wish to receive any further material from Engineering Heritage Paving Our Ways – A History of the World's Australia, contact EHA at : Roads and Pavements 24 [email protected] Connections 25 Subscribe: Readers who want to be added to the 2021 Australasian Engineering Heritage Conference 27 subscriber list can contact EHA via our email at : [email protected] We ran out of space in Connections, Readers wishing to submit material for publication so here is a story about Midget Submarines. -

AHSA 1989 AH Vol 25 No 04.Pdf

VOLUME 25 aviation NUMBER 4 / I ■ wsm HERITAOE mi ii* I >•1 THE JOURNAL OF THE AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA BRIiil ■ i; Registered by Australia Post Publication No. VBQ154 * 1 FE 2B crashed on taking offfrom makeshift airfield in a farmer’s paddock. Royal Australian Navy personnel formed salvage team. (RAAF MUSEUM POINT COOK) German propaganda experts made much of the 'Wolfchen and its exploits on the "Wo^ s raiding voyage. Aviation Heritage Vol 25. No. 4 72 VOLUME 25 Z/^IATION HERITAGE NUMBER 4 I--------------------- 1 I-------------- J THE JOURNAL OF THE AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA CONTENTS EDITORIAL Page 74 The Air search for the Raider Wolf By Bert Cookson Page 82 ■ini* The RAF Vulcan in Australia By Dr. Denis O’Brien Page 93 Information Echo Vulcan VH480 flies over RAAF Laverton Base at an air show on 19 September 1965 (John Hop ton) Cover photo. Vulcan XH 481 at the end of its non-stop flight to Australia,July 1961. Once again the idea of Australia having a national repository where our rich aviation history could be preserved has been brought to public attention. AHS A AND EDITORIAL ADDRESS Recentnews of a proposed National Air and Space Museum has raised an issue that has been P.O. Box 287, Cheltenham, Victoria. 3192 on and off the political agenda for many years. EDITORIAL COMMITTEE The fact that, for the most part, preserving Australia’s avation heritage is still the result of David Anderson Dion Makowski the work and entepreneurial approach of a dedicated few is fair indication of the level of Denis Baker Bob Wills Fred Morton commitment of Australian government at all levels to the preservation and presentation of Australian aviation history. -

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. Use “Ctrl F” to search Current to Vol 74 Item Vol Page Item Vol Page This Index is set out under the Aircraft armour 65 12 following headings. Airbus A300 16 12 Airbus A340 accident 43 9 Airbus A350 37 6 Aircraft. Airbus A350-1000 56 12 Anthony Element. Airbus A400 Avalon 2013 2 Airbus Beluga 66 6 Arthur Fry Airbus KC-30A 36 12 Bases/Units. Air Cam 47 8 Biographies. Alenia C-27 39 6 All the RAAF’s aircraft – 2021 73 6 Computer Tips. ANA’s DC3 73 8 Courses. Ansett’s Caribou 8 3 DVA Issues. ARDU Mirage 59 5 Avro Ansons mid air crash 65 3 Equipment. Avro Lancaster 30 16 Gatherings. 69 16 General. Avro Vulcan 9 10 Health Issues. B B2 Spirit bomber 63 12 In Memory Of. B-24 Liberator 39 9 Jeff Pedrina’s Patter. 46 9 B-32 Dominator 65 12 John Laming. Beaufighter 61 9 Opinions. Bell P-59 38 9 Page 3 Girls. Black Hawk chopper 74 6 Bloodhound Missile 38 20 People I meet. 41 10 People, photos of. Bloodhounds at Darwin 48 3 Reunions/News. Boeing 307 11 8 Scootaville 55 16 Boeing 707 – how and why 47 10 Sick Parade. Boeing 707 lost in accident 56 5 Sporting Teams. Boeing 737 Max problems 65 16 Squadrons. Boeing 737 VIP 12 11 Boeing 737 Wedgetail 20 10 Survey results. Boeing new 777X 64 16 Videos Boeing 787 53 9 Where are they now Boeing B-29 12 6 Boeing B-52 32 15 Boeing C-17 66 9 Boeing KC-46A 65 16 Aircraft Boeing’s Phantom Eye 43 8 10 Sqn Neptune 70 3 Boeing Sea Knight (UH-46) 53 8 34 Squadron Elephant walk 69 9 Boomerang 64 14 A A2-295 goes to Scottsdale 48 6 C C-130A wing repair problems 33 11 A2-767 35 13 CAC CA-31 Trainer project 63 8 36 14 CAC Kangaroo 72 5 A2-771 to Amberley museum 32 20 Canberra A84-201 43 15 A2-1022 to Caloundra RSL 36 14 67 15 37 16 Canberra – 2 Sqn pre-flight 62 5 38 13 Canberra – engine change 62 5 39 12 Canberras firing up at Amberley 72 3 A4-208 at Oakey 8 3 Caribou A4-147 crash at Tapini 71 6 A4-233 Caribou landing on nose wheel 6 8 Caribou A4-173 accident at Ba To 71 17 A4-1022 being rebuilt 1967 71 5 Caribou A4-208 71 8 AIM-7 Sparrow missile 70 3 Page 1 of 153 RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. -

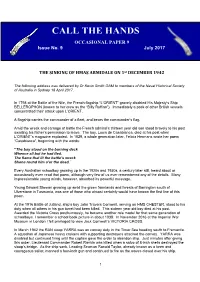

CALL the HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 9 Issue No

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 9 Issue No. 9 July 2017 THE SINKING OF HMAS ARMIDALE ON 1st DECEMBER 1942 The following address was delivered by Dr Kevin Smith OAM to members of the Naval Historical Society of Australia in Sydney 18 April 2017. In 1798 at the Battle of the Nile, the French flagship “L’ORIENT” gravely disabled His Majesty’s Ship BELLEROPHON (known to her crew as the “Billy Ruffian”). Immediately a pack of other British vessels concentrated their attack upon L’ORIENT. A flagship carries the commander of a fleet, and bears the commander’s flag. Amid the wreck and carnage of battle the French admiral’s thirteen year old son stood bravely to his post awaiting his father’s permission to leave. The boy, Louis de Casabianca, died at his post when L’ORIENT’s magazine exploded. In 1829, a whole generation later, Felicia Hermans wrote her poem “Casabianca”, beginning with the words: “The boy stood on the burning deck Whence all but he had fled. The flame that lit the battle’s wreck Shone round him o’er the dead.” Every Australian schoolboy growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, a century later still, heard about or occasionally even read that poem, although very few of us ever remembered any of the details. Many impressionable young minds, however, absorbed its powerful message. Young Edward Sheean growing up amid the green farmlands and forests of Barrington south of Ulverstone in Tasmania, was one of those who almost certainly would have known the first line of this poem.