Dark Side of the Boom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York

P o s t - War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York, 10 May 2016, Sale #12152 [All sold prices include buyer’s premium] Lots sold: 52 Total:$318,388,000 / £220,796,117 /€279,600,000 87% sold by lot Lots offered: 60 £0.69= $1 / €0.88=$1 91% sold by value Lot Description Estimate ($) Price Realized $57,285,000 Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Untitled, acrylic on 36B canvas, Painted in 1982 Estimate on Request £39,726,075 €50,213,758 $32,645,000 Mark Rothko (1903-1970), No. 17, oil on canvas, Painted in $30,000,000 - 17B £22,638,696 1957 $40,000,000 €28,615,312 $28,165,000 Clyfford Still (1904-1980), PH-234, oil on canvas, Painted in $25,000,000 - 28B £19,531,900 1948 $35,000,000 €24,688,321 $13,605,000 Christopher Wool (B. 1955), And If You, enamel on $12,000,000 - 5B aluminum, Painted in 1992 $18,000,000 £9,434,813 €11,925,603 $10,693,000 Agnes Martin (1912-2004), Orange Grove, oil and graphite $6,500,000 - 25B £7,415,395 on canvas, Painted in 1965 $8,500,000 €9,373,060 $9,797,036 Joan Mitchell (1925-1992), Noon, oil on canvas, Painted in $5,000,000 - 18B £6,794,036 1969 $7,000,000 €8,587,661 $9,685,000 Richard Prince (B. 1949), Runaway Nurse, inkjet and $7,000,000 - 38B £6,716,366 acrylic on canvas, Painted in 2007 $10,000,000 €8,489,487 $9,349,00 Robert Ryman (B. -

$495 Million Highest Total in Auction History

PRESS RELEASE | N E W Y O R K FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 5 M A Y 2 0 1 3 MAY 2013 POST-WAR AND CONTEMPORARY ART EVENING SALE ACHIEVED $495 MILLION HIGHEST TOTAL IN AUCTION HISTORY Christie’s auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen, hammers down Jackson Pollock’s Number 19, 1948, which achieved the highest price for the artist at $58.3 million POLLOCK’S NUMBER 19, 1948, SOLD FOR $58M (£38.5M / €45.5M) A WORLD AUCTION RECORD FOR THE ARTIST LICHTENSTEIN’S WOMAN WITH FLOWERED HAT REALIZED $56M (£37M / €43M) A WORLD AUCTION RECORD FOR THE ARTIST DUSTHEADS FETCHED $48.8M (£32M / €38M), SETTING A NEW WORLD AUCTION RECORD FOR BASQUIAT GUSTON’S TO FELLINI, ACHIEVED $25.8 (£17M / €20) WORLD AUCTION RECORD FOR THE ARTIST STRONG INTERNATIONAL DEMAND FOR MASTERPIECES AND WORKS FROM PRESTIGIOUS PROVENANCE 16 NEW ARTIST RECORDS SET 3 WORKS SOLD ABOVE $40 MILLION, 9 ABOVE $10 MILLION, AND 59 ABOVE $1 MILLION New York – On May 15th Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art evening sale achieved a staggering $495,021,500 (£326,714,190/ €386,116,770), with a remarkably strong sell-through rate of 94% by value and by lot. Bidders from around the world competed for an exceptional array of Abstract Expressionist, Pop and Contemporary works from some of the century’s most inspiring and influential artists, including Jackson Pollock, Roy Lichtenstein and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The sale featured a range of superlative works from distinguished private collections and institutions, such as the Collection of Celeste and Armand Bartos and the Estate of Andy Williams. -

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863)

1/44 Data Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) Pays : France Langue : Français Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Saint-Maurice (Val-de-Marne), 26-04-1798 Mort : Paris (France), 13-08-1863 Activité commerciale : Éditeur Note : Peintre, aquarelliste, graveur et lithographe Domaines : Peinture Autres formes du nom : Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) Delacroix (1798-1863) Dorakurowa (1798-1863) (japonais) 30 30 30 30 30 C9 E9 AF ED EF (1798-1863) (japonais) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 2098 8878 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) : œuvres (416 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres iconographiques (312) Hamlet Étude pour les Femmes d'Alger (1837) (1833) Faust (1825) Voir plus de documents de ce genre Œuvres textuelles (80) Journal "Hamlet" (1822) (1600) de William Shakespeare avec Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) comme Illustrateur Voir plus de documents de ce genre data.bnf.fr 2/44 Data Œuvres des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs (11) Lutte de Jacob avec l'Ange Héliodore chassé du temple (1855) (1855) La chasse aux lions Prise de Constantinople par les croisés : 1840 (1855) (1840) Médée furieuse La bataille de Taillebourg 21 juillet 1242 (1838) (1837) Femmes d'Alger dans leur appartement La bataille de Nancy, mort du duc de Bourgogne, (1834) Charles le Téméraire (1831) La liberté guidant le peuple La mort de Sardanapale (1830) (1827) Dante et Virgile aux Enfers (1822) Manuscrits et archives (13) "DELACROIX (Eugène), peintre, membre de l'Institut. "Cavalier arabe tenant son cheval par la bride, par (NAF 28420 (53))" -

Recovering Stolen Art and Antiquities Under the Forfeiture Laws: Who Is Entitled to Property When There Are Conflicting Claims

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 45 Number 2 Article 5 4-1-2020 Recovering Stolen Art and Antiquities Under the Forfeiture Laws: Who is Entitled to Property When there are Conflicting Claims Stefan D. Cassella Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Stefan D. Cassella, Recovering Stolen Art and Antiquities Under the Forfeiture Laws: Who is Entitled to Property When there are Conflicting Claims, 45 N.C. J. INT'L L. & COM. REG. 393 (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol45/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recovering Stolen Art and Antiquities Under the Forfeiture Laws: Who is Entitled to the Property When There are Conflicting Claims By Stefan D. Cassella†1 I. Introduction ............................................................... 394 II. Overview of Forfeiture Law ...................................... 396 A. What is the Government’s Interest? .................... 396 B. Criminal and Civil Forfeiture ............................. 397 1. Criminal forfeiture ......................................... 398 2. Civil forfeiture ............................................... 399 3. The innocent owner defense .......................... 401 4. Parallel civil and criminal proceedings .......... 402 III. Theories of Forfeiture ................................................ 403 A. The Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA)… ............................................................. 403 1. Eighteenth Century Peruvian Oil on Canvas . 404 2. -

FOE Issue Special May-16.Indd

FAMILY OFFICE ELITE SPECIAL EDITION BNY Mellon Cory McCruden FAMILY OFFICES - UHNWI - WEALTH - PHILANTHROPY- FINE ART - LUXURY - LIFESTYLE Subscription $100 per year www.familyoffi ceelite.com DOMOS FINE ART FINE ART DOMOS CONSULTANTS DOMOS FINE ART has a portfolio of very Fine Art on sale (Off Market) on behalf of our clients which include works by Caravaggio, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Rembrandt, Picasso, Rouault, Bonnard, Raphael and more. DOMOS FINE ART is experienced in dealing We off er the following services with rare off -market Valuation and Sale of Fine Art collections of fi ne art. Locate specifi c pieces of Fine Art Assist in verifying provenance of Art Auction representation UK Offi ce | TEL: + 44 (0) 29 2125 1994 | SKYPE: domosfi neart | [email protected] | www.domos.co.uk FAMILY OFFICEELITE MAGAZINE WHAT IS A FINE ART FAMILY OFFICE US CONGRESS INVESTING ENACT NEW TAX FOR FAMILY OFFICES EXAMINATION 03CAPLIN & DRYSDALE 37 ROLLS ROYCE BERNIE MADOFF BLACK BADGE THE INSIDE STORY ON 25 EXPOSING MADOFF FRANK CASEY 11 43 VIDEO ADVERTS MAYBACH THE FUTURE OF ADVERTISING SESURITY & PROTECTION WITH THE 600 GUARD 17 53 IMPACT INVESTING FAMILY OFFICE IN THE FAMILY OFFICE MULTI-FAMILY OFFICE SELECTION HOLLAND & HOLLAND 21 EXPLORE THE WORLD OF 57 ANTIQUE WEAPONS AFRICA THE SAFRA OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOUNDATION FAMILY OFFICES SAFRA FOUNDATION MAKES ING BANK DONATION TO CLINATEC 25 35 61 1 FAMILY OFFICE ELITE MAGAZINE GULF STREAM 63 100TH G-560 COREY McCRUDEN Cory McCruden BNY Mellon HADHUNTERS 71 Wealth Management, Advisory Services PROPER EXECUTIVE PLACEMENT SUPERYACHT 73 CHARTER - LUXURY VACATION FAMILY OFFICE 7 WHAT TO DO WITH CASH 77 MAN-VS-MACHINE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT 79 PRIVATE BANKS 83 WITH AN INVESTMENT FLOVOUR AUTHENTICITY IN THE ART MARKET 95 IMPACT AND 101 PHILANTHROPY OTHER STORIES.. -

1 How Modern Art Serves the Rich by Rachel Wetzler the New Republic

1 How Modern Art Serves the Rich By Rachel Wetzler The New Republic, February 26, 2018 During the late 1950s and 1960s, Robert and Ethel Scull, owners of a lucrative taxi company, became fixtures on the New York gallery circuit, buying up the work of then-emerging Abstract Expressionist, Minimalist, and Pop artists in droves. Described by Tom Wolfe as “the folk heroes of every social climber who ever hit New York”—Robert was a high school drop-out from the Bronx—the Sculls shrewdly recognized that establishing themselves as influential art collectors offered access to the upper echelons of Manhattan society in a way that nouveau riche “taxi tycoon” did not. Then, on October 18, 1973, in front of a slew of television cameras and a packed salesroom at the auction house Sotheby Parke Bernet, they put 50 works from their collection up for sale, ultimately netting $2.2 million—an unheard of sum for contemporary American art. More spectacular was the disparity between what the Sculls had initially paid, in some cases only a few years prior to the sale, and the prices they commanded at auction: A painting by Cy Twombly, originally purchased for $750, went for $40,000; Jasper Johns’s Double White Map, bought in 1965 for around $10,000, sold for $240,000. Robert Rauschenberg, who had sold his 1958 work Thaw to the Sculls for $900 and now saw it bring in $85,000, infamously confronted Robert Scull after the sale, shoving the collector and accusing him of exploiting artists’ labor. In a scathing essay published the following month in New York magazine, titled “Profit Without Honor,” the critic Barbara Rose described the sale as the moment “when the art world collapsed.” In retrospect, the Sculls’ auction looks more like the beginning than the end. -

«Beauty Is the True Scandal in Today's Art»

6/28/2018 "Beauty is the true scandal in today's art" | NZZ INTERVIEW «Beauty is the true scandal in today's art» Wolfgang Beltracchi has made a career as an art forger and was convicted. Now he leads a second life as an artist with his own handwriting. He keeps little of the genius cult - as well as of the international art scene, which celebrates the ugly above all. In a big interview he disenchanted the myths of the art business. René Scheu 26.6.2018, 05:30 clock Mr. Beltracchi, when you perform or exhibit, people come in droves. Then fall reliably the predicates "master counterfeiters" or "century counterfeiters". What sound do these words have for you? Oh. Hm. "Master" is not bad. (Consider.) Look: I see myself as a master painter, that's how I really understand myself, as a master of my craft. I have, I believe, sufficiently proven that I master the subject. ADVERTISING inRead invented by Teads Alone, art is more than painting – or has the 20th century not taken place in your eyes? https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/schoenheit-ist-in-der-heutigen-kunst-das-wahre-skandalon-ld.1397738 1/15 6/28/2018 "Beauty is the true scandal in today's art" | NZZ Yes, yes, something has already happened. And art history is also one of my hobbyhorses. Only, I'm not one of those who think that art has to be ugly and repulsive so that it turns out to be art. That would mean that fine art is not art. -

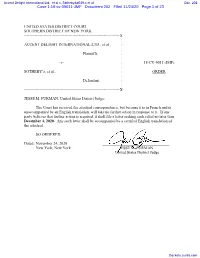

ORDER. the Court Has Received the Attached Correspondence, But

Accent Delight International Ltd. et al v. Sotheby's et al Doc. 202 Case 1:18-cv-09011-JMF Document 202 Filed 11/24/20 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------------- X : ACCENT DELIGHT INTERNATIONAL LTD., et al., : : Plaintiffs, : : -v- : 18-CV-9011 (JMF) : SOTHEBY’s, et al., : ORDER : Defendant. : : ------------------------------------------------------------------------- X JESSE M. FURMAN, United States District Judge: The Court has received the attached correspondence, but because it is in French and is unaccompanied by an English translation, will take no further action in response to it. If any party believes that further action is required, it shall file a letter seeking such relief no later than December 4, 2020. Any such letter shall be accompanied by a certified English translation of the attached. SO ORDERED. Dated: November 24, 2020 __________________________________ New York, New York JESSE M. FURMAN United States District Judge Dockets.Justia.com Case 1:18-cv-09011-JMF Document 202 Filed 11/24/20 Page 2 of 23 Republique et canton de Geneve Geneve, le 1er octobre 2020 POUVOIR JUDICIAIRE Tribunal civil CR/14/2020 2 COO XCR Tribunal de premiere instance Rue de l'Athenee 6-8 !A-PRIORITY! Case postale 3736 CH - 1211 GENEVE 3 R II II IIIIIIIII II IIIIII Ill 1111111111111111111 Avis de reception R P371 89506 7 CH Please scan - Signature required Veuillez scanner- Remlse contre signature UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTFORTHESOUTHEM DISTRICT NY Honorable Jesse M. Furman 40 Centre Street, Room 2202 10007 New York NY ETATS-U.NIS Ref : CR/14/2020 2 COO XCR a rappeler !ors de toute communication Votre ref: 1 :18-CV-09+011-JMF-RWL Nous vous remettons ci-joint copie de l'ordonnance dans la cause mention nee sous rubrique. -

Mulaifi to Resign After Shaddadiya Accident

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 RAJAB 15, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Pedophile A future of UN talks Djokovic US teacher thirst: Water take aim wins in Rome abused scores, crisis lies on at ‘killer on return clues14 missed the15 horizon robots’27 from20 injury Mulaifi to resign after Max 35º Min 22º Shaddadiya accident High Tide 11:08 Low Tide Two workers killed at university construction site 05:22 & 18:12 40 PAGES NO: 16165 150 FILS By A Saleh & Hanan Al-Saadoun KUWAIT: Two Egyptian workers were killed at a mega Local camel herders take no precautions university construction site yesterday, and Education Minister Ahmad Al-Mulaifi is expected to resign follow- By Nawara Fattahova ing the incident. The incident happened at Kuwait University’s Shaddadiya site where at least two workers KUWAIT: Despite warnings from neighboring were buried in an 8-m deep hole after a landslide. The Saudi Arabia about the link between camels and victims were identified as Majdi Faraj Salem Al-Sayed cases of the coronavirus known as MERS (Middle and Mohammad Rabeia Ahmad Hassan. Meanwhile, a East Respiratory Syndrome), no camel breeders or search was ongoing for a potential third worker who herders in Kuwait are taking precautions to protect could have been buried under the sand as well, accord- themselves against potential transmission. On ing to unconfirmed Sunday, Riyadh warned anyone working with reports. camels to take extra precautions and to wear Shortly after news gloves and masks. But in Kuwait yesterday at the about the incident camel market in Kabd, workers and breeders were broke, reports suggest- freely mixing with the camels, feeding and caring ed that Mulaifi is plan- for the desert animal without masks, gloves or oth- ning to resign in order er precautions. -

The Innovators Issue Table of Contents

In partnership with 51 Trailblazers, Dreamers, and Pioneers Transforming the Art Industry The Swift, Cruel, Incredible Rise of Amoako Boafo How COVID-19 Forced Auction Houses to Reinvent Themselves The Innovators Issue Table of Contents 4 57 81 Marketplace What Does a Post- Data Dive COVID Auction by Julia Halperin • What sold at the height of the House Look Like? COVID-19 shutdown? by Eileen Kinsella • Which country’s art • 3 top collectors on what they market was hardest hit? buy (and why) The global shutdown threw • What price points proved the live auction business into • The top 10 lots of 2020 (so far) most resilient? disarray, depleting traditional in every major category houses of expected revenue. • Who are today’s most Here’s how they’re evolving to bankable artists? 25 survive. The Innovators List 65 91 At a time of unprecedented How Amoako Art Is an Asset. change, we scoured the globe Boafo Became the Here’s How to to bring you 51 people who are Breakout Star of Make Sure It changing the way the art market Works for You functions—and will play a big a Pandemic Year role in shaping its future. In partnership with the by Nate Freeman ART Resources Team at Morgan Stanley The Ghanaian painter has become the art industry’s • A guide to how the art market newest obsession. Now, he’s relates to financial markets committed to seizing control of his own market. • Morgan Stanley’s ART Resources Team on how to integrate art into your portfolio 2 Editors’ Letter The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the art world to reckon with quite a few -

The Japanese Collector Recently Set the Auction Record for Jean-Michel Basquiat—Twice

AiA Art News-service MARKET THE 200 TOP COLLECTORS Maezawa’s World: The Japanese Collector Recently Set the Auction Record for Jean-Michel Basquiat—Twice BY Nate Freeman POSTED 09/11/17 11:50 PM 241 150 1 407 Yusaku Maezawa photographed in his home in Tokyo, 2017. ©KOHEY KANNO It was just after 8 p.m. on May 18, 2017, when a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for more than $110 million at Sotheby’s, blasting past the pre-sale estimate of $60 million. It set a new auction record for the artist and became the sixth most expensive artwork ever to sell at auction. The initial reaction in the salesroom was a collective gasp, followed by wild applause—and then, perhaps, some quick mental tabulations in the minds of collectors with Basquiats on their walls. Next, everyone started to wonder: who bought the damn thing? All was revealed within minutes, when Japanese collector Yusaku Maezawa posted an image to his lively Instagram account of himself standing in front of the untitled black-on-blue skull from 1982. “I am happy to announce that I just won this masterpiece,” he wrote in the caption. The purchase capped Maezawa’s lightning-fast shoot to the front of the global collecting rat race, and the folk story of the sky-high total soon became a crossover sensation. Once again, the world was talking about the American artist who died of a heroin overdose on Great Jones Street in 1988, when he was only 27 years old. An illustration of Yusaku Maezawa’s infamous Instagram post by Alexandra Compain-Tissier. -

Reading Sample

BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 1 20.11.19 14:31 EDITED BY DIETER BUCHHART AND ELEANOR NAIRNE WITH LOTTE JOHNSON 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 2 20.11.19 14:31 BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL PRESTEL MUNICH · LONDON · NEW YORK 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 3 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 4 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 5 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 6 20.11.19 14:31 8 FOREWORD JANE ALISON 4. JAZZ 12 BOOM, BOOM, BOOM FOR REAL 156 INTRODUCTION DIETER BUCHHART 158 BASQUIAT, BIRD, BEAT AND BOP 20 THE PERFORMANCE OF FRANCESCO MARTINELLI JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT ELEANOR NAIRNE 162 WORKS 178 ARCHIVE 1. SAMO© 5. ENCYCLOPAEDIA 28 INTRODUCTION 188 INTRODUCTION 30 THE SHADOWS 190 BASQUIAT’S BOOKS CHRISTIAN CAMPBELL ELEANOR NAIRNE 33 WORKS 194 WORKS 58 ARCHIVE 224 ARCHIVE 2. NEW YORK/ 6. THE SCREEN NEW WAVE 232 INTRODUCTION 66 INTRODUCTION 234 SCREENS, STEREOTYPES, SUBJECTS JORDANA MOORE SAGGESE 68 EXHIBITIONISM CARLO MCCORMICK 242 WORKS 72 WORKS 252 ARCHIVE 90 ARCHIVE 262 INTERVIEW BETWEEN 3. THE SCENE JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, GEOFF DUNLOP AND SANDY NAIRNE 98 INTRODUCTION 268 CHRONOLOGY 100 SAMO©’S NEW YORK LOTTE JOHNSON GLENN O’BRIEN 280 ENDNOTES 104 WORKS 288 INDEX 146 ARCHIVE 294 AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES 295 IMAGE CREDITS 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 7 20.11.19 14:31 Edo Bertoglio. Jean-Michel Basquiat wearing an American football helmet, 1981. 8 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 8 20.11.19 14:31 FOREWORD JANE ALISON Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the most significant painters This is therefore a timely presentation of a formidable talent of the 20th century; his name has become synonymous with and builds on an important history of Basquiat exhibitions notions of cool.