The Relational Power of God. Considering the Rebel Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shadows of Being

Shadows of Being Shadows of Being Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič Shadows of Being: Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Marko Uršič All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1593-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1593-2 To my dear parents Mila and Stanko who gave me life Just being alive! —miraculous to be in cherry blossom shadows! Kobayashi Issa 斯う活て 居るも不思議ぞ 花の陰 一茶 Kō ikite iru mo fushigi zo hana no kage TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Shadows of Ideas 1.1 Metaphysical essence of shadow, Platonism.................................... 2 1.2 The Sun and shadows in Ancient Egypt .......................................... 6 1.3 From Homeric to Orphic shadows ................................................. 15 Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

First Theology Requirement

FIRST THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT THEO 10001, 20001 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY: BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL **GENERAL DESCRIPTION** This course, prerequisite to all other courses in Theology, offers a critical study of the Bible and the early Catholic traditions. Following an introduction to the Old and New Testament, students follow major post biblical developments in Christian life and worship (e.g. liturgy, theology, doctrine, asceticism), emphasizing the first five centuries. Several short papers, reading assignments and a final examination are required. THEO 20001/01 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL GIFFORD GROBIEN 11:00-12:15 TR THEO 20001/02 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 12:30-1:45 TR THEO 20001/03 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 1:55-2:45 MWF THEO 20001/04 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 9:35-10:25 MWF THEO 20001/05 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 4:30-5:45 MW THEO 20001/06 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 3:00-4:15 MW 1 SECOND THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT Prerequisite Three 3 credits of Theology (10001, 13183, 20001, or 20002) THEO 20103 ONE JESUS & HIS MANY PORTRAITS 9:30-10:45 TR JOHN MEIER XLIST CST 20103 This course explores the many different faith-portraits of Jesus painted by the various books of the New Testament, in other words, the many ways in which and the many emphases with which the story of Jesus is told by different New Testament authors. The class lectures will focus on the formulas of faith composed prior to Paul (A.D. 30-50), the story of Jesus underlying Paul's epistles (A.D. -

UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY of CHRISTIANITY Contents 4.0

1 UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF CHRISTIANITY Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Christian Philosophy and Philosophy of Christianity 4.3 Difficulties in Formulating a Philosophy of Christianity 4.4 Concept of God 4.5 Incarnation 4.6 Concept of the Human Person 4.7 Human Free Will and the Problem of Evil 4.8 Concept of the World and Relationship between God and the World 4.9 Eschatology 4.10 Let us Sum Up 4.11 Key Words 4.12 Further Readings and References 4.0 OBJECTIVES What this present unit proposes is a Philosophy of Christianity. A course on the ‘Philosophy of Christianity’ would mean understanding how the Christian religion looks at world, man, and God. Who is man in Christianity? Why was human life created, sustained? Where is human life destined? What is the understanding of God in Christianity? What is World? What is the relationship between world, man and God? 4.1 INTRODUCTION Of the two terms that constitute the title ‘Philosophy of Christianity’, we are familiar with the word ‘Philosophy’, and we have a basic understanding of its scope and importance. The second term ‘Christianity’ may require a brief introduction. Christianity, a monotheistic major world religion, is an offshoot of Judaism. It began as a Jewish reform movement after the Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension of Jesus Christ and the Pentecost event, in circa 30 CE. Christianity took a systematized form as ‘historical Christianity’ through a triple combination: Jewish faith, Greek thought, and the conversion of a great part of the Roman Empire. Greek philosophy played a primal role in the formulation and interpretation of the Christian doctrines. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

ENCOUNTERS in FAITH Christianity in Interreligious Dialogue

ENCOUNTERS IN FAITH Christianity in Interreligious Dialogue Peter Feldmeier 100162_Encounter in Faith_with index.indd 3 1/14/2011 8:47:24 AM Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover art royalty-free from iStock The scriptural quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition Copyright © 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2011 by Peter Feldmeier. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. Printed in the United States of America 7032 ISBN 978-1-59982-031-6 100162_Encounter in Faith_with index.indd 4 1/14/2011 8:47:24 AM Contents Introduction ix How to Use This Book xii 1. Christianity in a Multireligious world 1 A Starting Point 1 The History of Christian Thought about Non-Christians 5 The Modern Theology of Religions 8 Holding a Postmodern Creative Tension 16 Hopes and Postures in Encountering the Other 19 2. Mysticism 23 What Is Mysticism? 23 Mysticism as Apophatic 27 Mysticism as Kataphatic 33 Conclusions 43 3. Masters and Mediators 47 The Role of a Mediator 47 Mediation and Cosmology 50 Spiritual Guides as Mediators 56 Lessons 65 Conclusions 67 4. The Jewish Vision 71 Entering the Jewish Imagination 71 Jewish Vision of Time 76 Torah Study: An Intersection between Time and Space 85 Jewish Vision of Space 88 5. -

Hinduism in Time and Space

Introduction: Hinduism in Time and Space Preview as a phenomenon of human culture, hinduism occupies a particular place in time and space. To begin our study of this phenomenon, it is essential to situate it temporally and spatially. We begin by considering how the concept of hinduism arose in the modern era as a way to designate a purportedly coherent system of beliefs and practices. since this initial construction has proven inadequate to the realities of the hindu religious terrain, we adopt “the hindu traditions” as a more satisfactory alternative to "hinduism." The phrase “hindu traditions” calls attention to the great diversity of practices and beliefs that can be described as “hindu.” Those traditions are deeply rooted in history and have flourished almost exclusively on the indian subcontinent within a rich cultural and religious matrix. As strange as it may seem, most Hindus do The Temporal Context not think of themselves as practicing a reli- gion called Hinduism. Only within the last Through most of the millennia of its history, two centuries has it even been possible for the religion we know today as Hinduism has them to think in this way. And although that not been called by that name. The word Hin- possibility now exists, many Hindus—if they duism (or Hindooism, as it was first spelled) even think of themselves as Hindus—do not did not exist until the late eighteenth or early regard “Hinduism” as their “religion.” This irony nineteenth century, when it began to appear relates directly to the history of the concept of sporadically in the discourse of the British Hinduism. -

The Marian Journal Keeping Members and Friends of the Order of the Most Holy Mary Theotokos Informed

The Marian Journal Keeping members and friends of the Order of the Most Holy Mary Theotokos informed. “The Old Catholic Marianists” February 2015 Volume 6, Number 1 In a sincere desire to share the joyful happiness of our hearts, we present this February 2015 edition of “The Marian Journal”. (The ordination of women to ministerial or priestly office is a regular practice among some major religious groups of the present time, as it was of several religions of antiquity. It remains a controversial issue in certain religions or denominations where the ordination, the process by which a person is consecrated and set apart for the administration of various religious rites, or where the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men. That traditional restriction might have been due to cultural prohibition or theological doctrine, or both. In some cases women have been permitted to be ordained, but not to hold higher positions, such as Bishop. In O.SS.T., we believe that all Holy Orders (bishops, priests, and deacons) are open to both men and women, single or married.) In this Issue: Women’s Ordination Women’s by Ordination Page 1. The Very Reverend Mother Aurore Leigh Barrett, O.SS.T. O.SS.T and The As I read the newspaper accounts of women trying to be ordained as priests, I am struck by the lack of understanding these women seem to have about Aisling Catholicism as a whole. There are many Catholic Jurisdictions that would Community enter welcome women as Ordained Priests, so it makes me question why these women into Agreement of insist that they only be ordained through the Roman Catholic Church. -

Willa Cather's Spirituality

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 7-12-1996 Willa Cather's Spirituality Mary Ellen Scofield Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Scofield, Mary Ellen, "Willa Cather's Spirituality" (1996). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5262. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Mary Ellen Scofield for the Master of Arts in English were presented July 12, 1996, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Sherrie Gradin Shelley Reed \ !'aye Powell Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: ********************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 21-<7 ~4?t4Y: /99C:. ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Mary Ellen Scofield for the Master of Arts in English presented July 12, 1996. Title: Willa Cather's Spirituality Both overtly and subtly, the early twentieth century American author Willa Cather (1873-1947) gives her readers a sense of a spiritual realm in the world of her novels. '!'his study explores Cather's changing <;onceptions of spirituality and ways_in which she portrays them in three ~ her novels. I propose that though Cather is seldom considered a modernist, her interest in spirituality parallels Virginia Woolf's interest in moments of heightened consciousness, and that she invented ways to express ineffable connections with a spiritual dimension of life. -

Mdm1012le If God Is Good Why Is There Evil

Dear Christian Leader, You are receiving this research brief because you have signed up for free leader equipping ministry resources at markdriscoll.org. I want to personally thank you for loving Jesus and serving his people. I also want to thank you for allowing me the honor of helping you lead and feed God’s people. This research brief is a gift from Mark Driscoll Ministries. It was prepared for me a few years ago by a professional research team. I am happy to make it available to you, and I would request that you not post it online. If you know of other Christian leaders who would like to receive it, they can do so by signing up for for free leadership resources at markdriscoll.org. It’s a great joy helping people learn about Jesus from the Bible, so thank you for allowing me to serve you. If you would be willing to support our ministry with an ongoing or one- time gift of any amount, we would be grateful for your partnership. A Nobody Trying to Tell Everybody About Somebody, Pastor Mark Driscoll 1 21001 NORTH TATUM BLVD | STE 1630-527 | PHOENIX, AZ 85050 | [email protected] MARKDRISCOLL.ORG If God is Good Why is There Evil? Research brief prepared by a research team How can evil or suffering be reconciled with the Christian affirmation of the goodness and power of the God who created the world? The problem of evil is three-legged stool: 1) God is all powerful, 2) God is good, and 3) evil really does exist. -

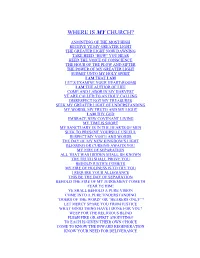

177 WHERE IS MY CHURCH.Pdf

WHERE IS MY CHURCH? ANOINTING OF THE MOST HIGH RECEIVE YE MY GREATER LIGHT THE GREATER LIGHT NOW DAWNING TAKE HEED “HOW” YOU HEAR HEED THE VOICE OF CONSCIENCE THE HOUR OF THE PLOW AND SIFTER THE POWER OF MY GREATER LIGHT SUBMIT UNTO MY HOLY SPIRIT I AM THAT I AM LET’S EXAMINE YOUR HEART-ROOMS I AM THE AUTHOR OF LIFE COME AND LABOR IN MY HARVEST YE ARE CALLED TO AN HOLY CALLING DISRESPECT NOT MY TREASURES SEEK MY GREATER LIGHT OF UNDERSTANDING MY WORDS, MY TRUTH AND MY LIGHT I AM THY GOD EMBRACE NEW COVENANT LIVING MY TIME IS SHORT MY SANCTUARY IS IN THE HEARTS OF MEN SEEK TO PRESENT YOURSELF USEFUL RESPECT MY VOICE AND WORDS THE DAY OF MY NEW KINGDOM’S LIGHT BLESSING OR CURSING AWAITS YOU MY FIRE OF SEPARATION ALL THAT WAS HIDDEN SHALL BE KNOWN THE TRUTH SHALL PROVE YOU BEHOLD JUSTICE COMETH MY FIRE OF HOLINESS IS TO TRY YOU I REQUIRE YOUR ALLEGIANCE THIS BE THE DAY OF SEPARATION BEHOLD THE FIRE OF MY JUDGEMENT COMETH FEAR YE HIM! YE SHALL BEHOLD A PURE VISION COME INTO A PURE UNDERSTANDING “DOERS OF THE WORD” OR “HEARERS ONLY”? LET MERCY SPARE YOU FROM JUSTICE WHAT GOOD THING HAVE I DONE FOR YOU? WEEP FOR THE RELIGIOUS BLIND FLESH FIRE OR SPIRIT ANOINTING? TO EACH IS GIVEN THEIR OWN CHOICE COME TO KNOW THE INWARD REGENERATION KNOW YOUR NEED FOR DELIVERANCE SEEK TO BECOME UNBOUNDED THE AVENUE UNTO REDEMPTION BLESSED ARE THEY... THE FULLNESS OF MY GOSPEL RETURN UNTO ME, O MY PEOPLE THE SEALING OF MY REMNANTS RIGHTEOUS TO BE SAVED IN THE KINGDOM OF GOD THE WORDS OF GOD MY WORD SHALL STAND OVERTURN, OVERTURN, OVERTURN! RIPENING IN INIQUITY -

The Influence of Shamanism on Korean Churches and How to Overcome It

Guillermin Library Liberty University Lynchburg, VA 24502 REFERENCE DO NOT CIRCULATE LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE INFLUENCE OF SHAMANISM ON KOREAN CHURCHES AND HOW TO OVERCOME IT A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MINISTRY By Jin - Woo Lee Ll9F) Lynchburg, Virginia May, 2000 Copyright 2000 Jin Woo Lee All Rights Reserved 11 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET GRADE MENTOR READER 111 ABSTRACT THE INFLUENCE OF SHAMANISM ON KOREAN CHURCHES AND HOW TO OVERCOME IT Jin Woo Lee Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 2000 Mentor: Dr. Frank J. Schmitt What problem do Korean churches have now? Korean churches have had serious growth problems since the 1990s'. Although Korean churches have grown rapidly with the economic growth of Korea, there have been many contributions and evil influences of shamanism, which lies deep in the minds of Korean people. Obviously, shamanism has made a contribution to growth of the Korean church since Christianity was introduced. Many churches and pastors have consented to or utilized such a tendency. However, this created serious problems. Shamanism is anti-Biblical. Shamanism brought about a theoretical combination, transmutation of religion and many mistakes in church life. A questionnaire was used to reveal; these facts. Ultimately, this thesis calls attention to shamanist elements in Korean churches and suggests how to eliminate them. Abstract length: 125 words IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Liberty University has become one of my almamaters. I have some good memories of going to the classrooms on the quiet snowy campus. There was also a great change in me while I was taking the courses. -

THE UNITY of GOD Introduction Monotheism, As a Word, Was Coined

CHAPTER SIX THE UNITY OF GOD René Munnik (Tilburg University) Introduction Monotheism, as a word, was coined in early modernity.1 It was meant to indicate religions, theologies or religious philosophies that apprehend God as “the one and only One for all.” The “oneness,” indicated by the prefix monos, had, and has, a triple meaning: it stands for God’s unique- ness—the “one and only, and no other”—, it stands for God’s unity— “One, no dividedness, fickleness or struggles within godself”—, and it stands for God’s universality—“for all, not for some.” Strictly speaking, these meanings do not necessarily imply each other, but orthodox “monotheism” generally holds that God is unique and universal because of God’s unity; whereas the gods being “many,” “particular” and “capricious” within and among themselves. Besides, “monotheism” is a word of controversies, in the sense that it is meant to exclude other ideas about God or the divine. Its natural place is within an arena of contested views, like polytheism, pantheism, deism, henotheism and even poly- demonism; all these words, again, being modern words. Hence, the use and meaning of this word “monotheism” presupposes a modern systematisation or taxonomy of different religious phenom- ena or theological convictions and their mutual antagonisms. It is hard to imagine why a non-Western, non-modern “polytheist” should con- sider himself as such, although he may in fact venerate “many gods.” It is against the background of the conceptual framework of modern 1 Henry More (1614-1687), a prominent member of the Cambridge Platonist School was among the first who used it.