“It's Still His Words”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

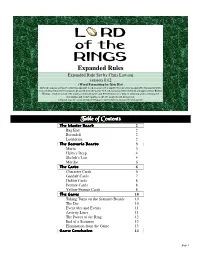

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson Version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) the Following Is a Rewrite of the Existing Rule Book

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) The following is a rewrite of the existing rule book. It is not yet complete but the sections included explain the rules in more detail than the existing set provided with the game. The following has been checked and approved by Reiner Knizia. (Author’s note: My thanks to Chris Bowyer and Reiner Knizia for help in checking and correcting the documents and to the citizens of the rec.games.board.newsgroup. Original may be found at http://freespac e.virgin.net/chris.lawson/rk/lotr/faq.htm Table of Contents The Master Board 2 Bag End 2 Rivendell 2 Lothlórien 2 The Scenario Boards 3 Moria 3 Helm’s Deep 4 Shelob’s Lair 5 Mordor 6 The Cards 6 Character Cards 6 Gandalf Cards 7 Hobbit Cards 8 Feature Cards 8 Yellow Feature Cards 8 The G am e 10 Taking Turns on the Scenario Boards 10 The Die 10 Event tiles and Events 11 Activity Lines 11 The Power of the Ring 12 End of a Scenario 13 Elimination from the Game 13 G am e Conclusion 14 Page 1 T he M aster Board The master board shows three locations (Bag End, Rivendell and Lothlórien) and four scenarios (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor). selects a card from hand and passes it to the player on the left. Bag End This continues until everyone has received and passed on one The game starts at Bag End. -

Catalog06.Pdf

$EAR&RIENDS 7ITHAPASSIONTOWARDCREATINGUNIQUE HIGHLYSOUGHTAFTERCOLLECTIBLES THE ARTISANS OF 3IDESHOW HAVE DISTINGUISHED THEMSELVES FOR THEIR CRAFTSMANSHIPANDCOMMITMENTTOAUTHENTICITY%ACHNEWITEMIS CAREFULLYCONSIDEREDFORITSCOLLECTIBLEVALUEANDDESIRABILITY!SASPECIALTY MARKET MANUFACTURER OF LICENSED AND PROPRIETARY COLLECTIBLE PRODUCTS 3IDESHOW#OLLECTIBLESHASBEENCREATINGMUSEUM QUALITYCOLLECTIBLEPIECES FORNEARLYYEARS4HECOMPANYSORIGINSINTHESPECIALEFFECTSAND MAKE UPINDUSTRYHAVEHELPEDTOESTABLISHITSPLACEOFREVERENCEINTHE COLLECTIBLEINDUSTRY7ORKINGFROMTHECREATIONSOFRENOWNEDSCULPTORS THEEXPERIENCEDMODEL MAKERS PAINTERSANDCOSTUMERSAT3IDESHOWCREATEINTRICATELYDETAILEDLIKENESSESOFPOPULAR CHARACTERS9OUWILLINSTANTLYRECOGNIZEMANYFAMOUSANDINFAMOUSFILMANDTELEVISIONMONSTERS VILLAINSANDHEROESASYOUGOTHROUGHTHISCATALOG4HEFOLLOWINGPAGESAREALSOFILLEDWITH SOMEWELL KNOWNSTARSOFCOMEDYANDMYSTICALCREATURESOFFANTASY 3IDESHOW#OLLECTIBLESISPROUDTOMANUFACTURERCOLLECTIBLEPRODUCTSBASEDONTHEFOLLOWING LICENSEDPROPERTIES4HE0LANETOFTHE!PES 4HE,ORDOFTHE2INGS (ELLBOY 6AN (ELSING *AMES "OND 5NIVERSAL 3TUDIOS #LASSIC -ONSTERS 4 *ASON &REDDY ,EATHERFACE 0LATOON 8&ILES "UFFYTHE6AMPIRE3LAYER 4HE3IMPSONS 3TAR4REK /UTER ,IMITS 4WILIGHT:ONE !RMYOF$ARKNESS -ONTY0YTHON AND*IM(ENSONS-UPPETS )NADDITION 3IDESHOWMANUFACTURERSITSOWNLINEOFHISTORICALLYACCURATEFIGURESUNDER THESE3IDESHOWTRADEMARKS"AYONETS"ARBED7IRE77) "ROTHERHOODOF!RMS!MERICAN #IVIL7AR AND3IX'UN,EGENDSHISTORICALFIGURESOFTHE!MERICAN7EST !NIMPORTANTELEMENTOF3IDESHOWSSUCCESSISTHEVALUABLEPARTNERSHIPSESTABLISHEDWITH INNOVATIVECOMPANIESANDCREATIVEPEOPLE3IDESHOWHASFORGEDRELATIONSHIPSWITHSPECIAL -

Orc Hosts, Armies and Legions: a Demographic Study

Volume 16 Number 4 Article 2 Summer 7-15-1990 Orc Hosts, Armies and Legions: A Demographic Study Tom Loback Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loback, Tom (1990) "Orc Hosts, Armies and Legions: A Demographic Study," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 16 : No. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol16/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Calculates the likely population of Orcs in Middle-earth at various times based on Tolkien’s use of the military terms host, army, and legion. Uses The Silmarillion and several volumes of The History of Middle- earth to “show a developing concept of Orc military organization and, by inference, an idea of Orc demographics.” Additional Keywords Tolkien, J.R.R.—Characters—Orcs—Demographics; Tolkien, J.R.R.—Characters—Orcs—History; Tolkien, J.R.R.—Characters—Orcs—Military organization This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

The Geology of Middle-Earth

Volume 21 Number 2 Article 50 Winter 10-15-1996 The Geology of Middle-earth William Antony Swithin Sarjeant Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sarjeant, William Antony Swithin (1996) "The Geology of Middle-earth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 50. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol21/iss2/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract A preliminary reconstruction of the geology of Middle-earth is attempted, utilizing data presented in text, maps and illustrations by its arch-explorer J.R.R. Tolkien. The tectonic reconstruction is developed from earlier findings yb R.C. Reynolds (1974). Six plates are now recognized, whose motions and collisions have created the mountains of Middle-earth and the rift structure down which the River Anduin flows. -

Treasures of Middle Earth

T M TREASURES OF MIDDLE-EARTH CONTENTS FOREWORD 5.0 CREATORS..............................................................................105 5.1 Eru and the Ainur.............................................................. 105 PART ONE 5.11 The Valar.....................................................................105 1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................ 2 5.12 The Maiar....................................................................106 2.0 USING TREASURES OF MIDDLE EARTH............................ 2 5.13 The Istari .....................................................................106 5.2 The Free Peoples ...............................................................107 3.0 GUIDELINES................................................................................ 3 5.21 Dwarves ...................................................................... 107 3.1 Abbreviations........................................................................ 3 5.22 Elves ............................................................................ 109 3.2 Definitions.............................................................................. 3 5.23 Ents .............................................................................. 111 3.3 Converting Statistics ............................................................ 4 5.24 Hobbits........................................................................ 111 3.31 Converting Hits and Bonuses...................................... 4 5.25 -

![A Dungeon Game SYNOPSIS Moria [ -O ] [ -R ] [ -S ] [ -S ] [ -N ] [ -W ] [ Savefile ] DESCRIPTION Moria Plays a Dungeon Game with You](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8549/a-dungeon-game-synopsis-moria-o-r-s-s-n-w-savefile-description-moria-plays-a-dungeon-game-with-you-878549.webp)

A Dungeon Game SYNOPSIS Moria [ -O ] [ -R ] [ -S ] [ -S ] [ -N ] [ -W ] [ Savefile ] DESCRIPTION Moria Plays a Dungeon Game with You

MORIA(6) GAMES AND DEMOS MORIA(6) NAME moria - a dungeon game SYNOPSIS moria [ -o ] [ -r ] [ -s ] [ -S ] [ -n ] [ -w ] [ savefile ] DESCRIPTION Moria plays a dungeon game with you. It lets you generate a character, lets you buy equipment, and lets you wander in a fathomless dungeon while finding treasure and being attacked by monsters and fellow adventurers. Typing ? gives you a list of commands. The ultimate object of moria is to kill the Balrog, which dwells on the 50th level of the dungeon, 2,500 feet under- ground. Most players never even reach the Balrog, and those that do seldom live to tell about it. For a more complete description of the game, read the docu- ment The Dungeons of Moria. By default, moria will save and restore games from a file called moria.save in your home directory. If the environ- ment variable MORIA_SAV is defined, then moria will use that file name instead of the default. If MORIA_SAV is not a complete path name, then the savefile will be created or restored from the current directory. You can also expli- citly specify a savefile on the command line. If you use the -n option, moria will create a new game, ignoring any savefile which may already exist. This works best when a savefile name is specified on the command line, as this will prevent moria from trying to overwrite the default savefile (if it exists) when you try to save your game. You move in various directions by pressing the numeric keypad keys, VMS-style. If you specify -r, you move the same way you do in rogue(6). -

A Middle-Earth Traveller John Howe Bok PDF Epub Fb2 Boken

A Middle-earth Traveller Ladda ner boken PDF John Howe A Middle-earth Traveller John Howe boken PDF Let acclaimed Tolkien artist John Howe take you on an unforgettable journey across Middle-earth, from Bag End to Mordor, in this richly illustrated sketchbook fully of previously unseen artwork, anecdotes and meditations on Middle-earth. Middle-earth has been mapped, Bilbo's and Frodo's journeys plotted and measured, but it remains a wilderland for all that. The roads as yet untravelled far outnumber those down which J.R.R. Tolkien led us in his writings. A Middle- earth Traveller presents a walking tour of Tolkien's Middle-earth, visiting not only places central to his stories, but also those just over the hill or beyond the horizon. Events from Tolkien's books are explored - battles of the different ages that are almost legend by the time of The Lord of the Rings; lost kingdoms and ancient myths, as well as those places only hinted at: kingdoms of the far North and lands beyond the seas. Sketches that have an `on-the-spot' feel to them are interwoven with the artist's observations gleaned from Tolkien's books as he paints pictures with his words as well as his pencil. He also recollects his time spent working alongside Peter Jackson on the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit film trilogies. Combining concept work produced for films, existing Middle-earth art and dozens of new paintings and sketches exclusive to this book, A Middle-earth Traveller will take the reader on a unique and unforgettable journey across Tolkien's magical landscape. -

Christian Elements in Lord of the Rings and Beowulf

Christian Elements in Lord of the Rings and Beowulf Dodig, Vedran Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:295197 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti i njemačkog jezika i književnosti Vedran Dodig Elementi kršćanstva u Gospodaru Prstenova i Beowulfu Diplomski rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Borislav Berić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti i njemačkog jezika i književnosti Vedran Dodig Elementi kršćanstva u Gospodaru Prstenova i Beowulfu Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje humnističke znanosti, polje filologija, grana anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Borislav Berić Osijek, 2016. J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences MA programme in English Language and Literature and German Language and Literature Vedran Dodig Christian Elements in The Lord of the Rings and Beowulf MA thesis Supervisor: Borislav Berić, docent Osijek, 2016 J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature MA programme in English Language and Literature and German Language and Literature Vedran Dodig Christian Elements in The Lord of the Rings and Beowulf MA thesis Humanities, field of Philology, branch of English Supervisor: Borislav Berić, docent Osijek, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………….……………… 6 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………..……. -

An Exploration of Character and Leadership in J.R.R Tolkien's Lord

MJUR 2017, Issue 7 37 Concerning Power: An Exploration of Character and Leadership in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings Brittany Andrews Crown College Abstract Although seldom studied as a commentary on leadership and the various forms of underlying power, The Lord of the Rings offers extended insight on power and its relation to human nature. Tolkien recognizes the potential evil of power, but he also understands humanity’s need for leadership and power. It is in this paradox that the studies of John French and Bertram Raven are immensely insightful. In a 1959 study and continuing research of more recent years, French and Raven conclude that there are six basic types of social power used to influence people. Each of these bases of power can be found in characters in The Lord of the Rings. They are portrayed in a way that helps to illuminate the importance that Tolkien places on utilizing self-awareness, teamwork, and community when exercising power. Although seldom studied as a commentary on leadership and various forms of underlying power, The Lord of the Rings offers extended insight on power and its relation to human nature. There can be little doubt that, on a surface level, Tolkien is wary of power—Middle Earth almost falls due to a malicious buildup of it. While Tolkien’s not so subtle allusions to Hitler’s ironworks and proliferation of weapons fashion some of Tolkien’s political commentary, his exploration of leadership and human nature have far-wider applications. Tolkien recognizes the potential evil of power and how easily humans are swayed by the influence it promises, yet he also understands humanity’s need for leadership. -

The Art of John Howe by John Howe Book

Myth and Magic: The Art of John Howe by John Howe book Ebook Myth and Magic: The Art of John Howe currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Myth and Magic: The Art of John Howe please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 144 pages+++Publisher:::: HarperCollins UK; First Edition edition (December 1, 2001)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0007107951+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0007107957+++Product Dimensions::::9.1 x 0.7 x 11 inches++++++ ISBN10 0007107951 ISBN13 978-0007107 Download here >> Description: For the first time ever, a portfolio of illustrated work from the award-winning artist, John Howe, which reveals the breathtaking vision of one of the foremost fantasy artists in the world. Myth and Magic is arranged into six sections, which looks at the books by J.R.R. Tolkien that have inspired John, as well as a fascinating tour through the paintings that he has produced for some of the finest fantasy authors working today. From the beloved painting of Smaug which decorates The Hobbit, his numerous and bestselling calendar illustrations, the world famous Gandalf picture, which is synonymous with the HarperCollins one-volume edition of The Lord of the Rings, this large-format hardback will delight fans of Tolkien, and anyone who has been captured by the imagination of the artist who so brilliantly brings to life the literary vision of J.R.R. Tolkien. I got the three volume version of Lord of the Rings with all the Alan Lee illustrations. Its a great set, the one that ought to be on the shelf of every Tolkien fan.