Magic, Enchantment, and the True Nature of Power in the Lord of the Rings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOTR and Beowulf: I Need a Hero

Jestice/English 4 Lord of the Rings and Beowulf: I need a hero! (100 points) Directions: 1. On your own paper, and as you watch the selected scenes, answer the following questions by comparing and contrasting the heroism of Frodo Baggins to that of Beowulf. (The scene numbers are from the extended version; however, the scene titles are consistent with the regular edition.) 2. Use short answer but complete sentences. Fellowship of the Ring Scene 10: The Shadow of the Past Gandalf already has shown Frodo the One Ring and has told Frodo he must keep it hidden and safe. Frodo obliges. But when Gandalf tells him the story of the ring and that Frodo must take it out of the Shire, Frodo’s reaction is different. 1. Explain why Frodo reacts the way he does. Is this behavior fitting for a hero? Why or why not? Is Frodo a hero at this point of the story? 2. How does this differ from Beowulf’s call to adventure? Scene 27: The Council of Elrond Leaders from across Middle Earth have gathered in the Elvish capital of Rivendell to discuss the fate of the One Ring. Frodo has taken the ring to Rivendell for safekeeping. Having already tried unsuccessfully to destroy the ring, the leaders argue about who should take it to be consumed in the fires of Mordor. Frodo steps forward and accepts the challenge. 1. Frodo’s physical stature makes this journey seem impossible. What kinds of traits apparent so far in the story will help him overcome this deficiency? 2. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

JRR Tolkien's Sub-Creations of Evil

Volume 36 Number 1 Article 7 10-15-2017 ‘A Warp of Horror’: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sub-creations of Evil Richard Angelo Bergen University of British Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bergen, Richard Angelo (2017) "‘A Warp of Horror’: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sub-creations of Evil," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 36 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol36/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Considers Tolkien’s skilled evocation of evil and the way he manages to hold Augustinian and Manichean conceptions of evil in balance, particularly in his depiction of orcs. Additional Keywords Augustine, St.—Concept of evil; Evil, Nature of, in J.R.R. -

Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University

Inklings Forever Volume 4 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fourth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 10 Lewis & Friends 3-2004 Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rearick, Anderson (2004) "Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc," Inklings Forever: Vol. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol4/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume IV A Collection of Essays Presented at The Fourth FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM ON C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2004 Upland, Indiana Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson Rearick, III Mount Vernon Nazarene University Rearick, Anderson. “Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc?” Inklings Forever 4 (2004) www.taylor.edu/cslewis 1 Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson M. Rearick, III The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien’s themselves out of sync with most of their peers, thus World1 underscoring the fact that Tolkien’s work has up until recently been the private domain of a select audience, In Jonathan Coe’s novel, The Rotters’ Club, a an audience who by their very nature may have confrontation takes place between two characters over inhibited serious critical examinations of Tolkien’s what one sees as racist elements in Tolkien’s Lord of work. -

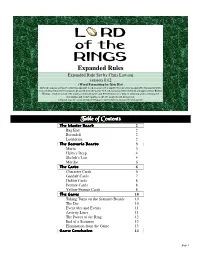

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson Version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) the Following Is a Rewrite of the Existing Rule Book

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) The following is a rewrite of the existing rule book. It is not yet complete but the sections included explain the rules in more detail than the existing set provided with the game. The following has been checked and approved by Reiner Knizia. (Author’s note: My thanks to Chris Bowyer and Reiner Knizia for help in checking and correcting the documents and to the citizens of the rec.games.board.newsgroup. Original may be found at http://freespac e.virgin.net/chris.lawson/rk/lotr/faq.htm Table of Contents The Master Board 2 Bag End 2 Rivendell 2 Lothlórien 2 The Scenario Boards 3 Moria 3 Helm’s Deep 4 Shelob’s Lair 5 Mordor 6 The Cards 6 Character Cards 6 Gandalf Cards 7 Hobbit Cards 8 Feature Cards 8 Yellow Feature Cards 8 The G am e 10 Taking Turns on the Scenario Boards 10 The Die 10 Event tiles and Events 11 Activity Lines 11 The Power of the Ring 12 End of a Scenario 13 Elimination from the Game 13 G am e Conclusion 14 Page 1 T he M aster Board The master board shows three locations (Bag End, Rivendell and Lothlórien) and four scenarios (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor). selects a card from hand and passes it to the player on the left. Bag End This continues until everyone has received and passed on one The game starts at Bag End. -

The Hidden Meaning of the Lord of the Rings the Theological Vision in Tolkien’S Fiction

LITERATURE The Hidden Meaning of The Lord of the Rings The Theological Vision in Tolkien’s Fiction Joseph Pearce LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing J.R.R. Tolkien: The Man behind the Myth...........................................4 LECTURE 2 True Myth: Tolkien, C.S. Lewis & the Truth of Fiction.............................................8 Feature: The Use of Language in The Lord of the Rings............................................12 LECTURE 3 The Meaning of the Ring: “To Rule Them All, and in the Darkness Bind Them”.......................................14 LECTURE 4 Of Elves & Men: Fighting the Long Defeat.................................................................18 Feature: The Scriptural Basis for Tolkien’s Middle-earth............................................22 LECTURE 5 Seeing Ourselves in the Story: The Hobbits, Boromir, Faramir, & Gollum as Everyman Figures.......... 24 LECTURE 6 Of Wizards & Kings: Frodo, Gandalf & Aragorn as Figures of Christ..... 28 Feature: The Five Races of Middle-earth................................................................................32 LECTURE 7 Beyond the Power of the Ring: The Riddle of Tom Bombadil & Other Neglected Characters....................34 LECTURE 8 Frodo’s Failure: The Triumph of Grace......................................................................... 38 Suggested Reading from Joseph Pearce................................................................................42 2 The Hidden Meaning -

Gandalf: One Wizard to Lead Them, One to Find Them, One to Bring Them And, Despite the Darkness, Unite Them

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 Gandalf: One Wizard to lead them, one to find them, one to bring them and, despite the darkness, unite them. Alex Gunn Middle Earth is a wonderful but strangely familiar place. The Hobbits, Elves, Men and other peoples who live in caves, forests, mountain ranges and stone cities, are all combined by Tolkien to create a fantasy world which is full of wonder, beauty and magic. However, looking past these fantastical elements, we can see that Middle Earth has many similarities to the society in which we live. The different races of Middle Earth have distinct and deep differences and often keep themselves separate from one another because of mutual distrust or dislike. Due to these divisions, only one person, one who does not belong to any particular race or people, can unite them for the coming war: Gandalf the Wizard who embodies the qualities needed to be an effective leader in our world. As Sue Kim points out in her book Beyond black and White: Race and Postmodernism in Lord of the Rings, Tolkien himself declared that, “the desire to converse with other living things is one of the great allurements of fantasy” (Kim 555). Given this belief, it is no surprise that Tolkien,‘fills his imagined worlds with a plethora of intelligent non human races and exotic ethnicities, all changing over time: Elves, Dwarves, Men, Hobbits, Ents, Trolls, Orcs, Wild Men, talking beasts and embodied spirits’ (Kim 555). This plethora, as Kim puts it, makes Gandalf an important literary tool for Tolkien because to believe that such a varied mix of people, creatures, races and ethnicities live in complete harmony would feel false and perhaps too convenient. -

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien Robin Veenman BA Thesis Tilburg University 18/06/2019 Supervisor: David Janssens Second reader: Sander Bax Abstract The work of J.R.R. Tolkien appears to resemble various aspects from Norse mythology and the Norse sagas. While many have researched these resemblances, few have done so specifically on the dark side of Tolkien’s work. Since Tolkien himself was fascinated with the dark side of literature and was of the opinion that monsters served an essential role within a story, I argue that both the monsters and Tolkien’s attraction to Norse mythology and sagas are essential phenomena within his work. Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter one: Tolkien’s Fascination with Norse mythology 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Humphrey Carpenter: Tolkien’s Biographer 8 1.3 Concrete Examples From Jakobsson and Shippey 9 1.4 St. Clair: an Overview 10 1.5 Kuseela’s Theory on Gandalf 11 1.6 Chapter Overview 12 Chapter two: The monsters Compared: Midgard vs Middle-earth 14 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Dragons 15 2.3 Dwarves 19 2.4 Orcs 23 2.5 Wargs 28 2.6 Wights 30 2.7 Trolls 34 2.8 Chapter Conclusion 38 Chapter three: The Meaning of Monsters 41 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 The Dark Side of Literature 42 3.3 A Horrifically Human Fascination 43 3.4 Demonstrare: the Applicability of Monsters 49 3.5 Chapter Conclusion 53 Chapter four: The 20th Century and the Northern Warrior-Ethos in Middle-earth 55 4.1 Introduction 55 4.2 An Author of His Century 57 4.3 Norse Warrior-Ethos 60 4.4 Chapter Conclusion 63 Discussion 65 Conclusion 68 Bibliography 71 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost I have to thank the person who is evidently at the start of most thesis acknowledgements -for I could not have done this without him-: my supervisor. -

Myth, Fantasy and Fairy-Story in Tolkien's Middle-Earth Buveneswary

MYTH, FANTASY AND FAIRY-STORY IN TOLKIEN’S MIDDLE-EARTH Malaya BUVENESWARY VATHEMURTHYof DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY MALAYA University2016 MYTH, FANTASY AND FAIRY-STORY IN TOLKIEN’S MIDDLE-EARTH BUVENESWARY VATHEMURTHYMalaya of DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University2016 Abstract This dissertation explores J.R.R. Tolkien’s ideas and beliefs on myth, fantasy and fairy story and their roles in portraying good and evil in his famous works. Indeed, many authors and critics such as Bradley J. Birzer, Patrick Curry, Joseph Pearce, Ursula Le Guin, and Jay Richards have researched Tolkien based on this connection. They have worked on the nature of good and evil in his stories, the relevance of Tolkien in contemporary society, and the importance of myth and fantasy. However, my original contribution would be to examine the pivotal roles of myth, fantasy and fairy story as a combined whole and to demonstrate that they depend on one another to convey truths about good and evil. This research is aimed at showing that Middle-earth evolves from a combination of these three genres. This is made evident by the way Tolkien crafted his lecture On Fairy Stories for a presentation at the AndrewMalaya Lang lecture at the University of St Andrews in 1939. This dissertation then examines Tolkien’s own definitions of myth, fantasy and fairy stories and his extensiveof research on these “old-fashioned” or forgotten genres. He believed they could provide a cure for the moral and human degradation triggered by modernism. -

Applying Anthropology to Fantasy: a Structural Analysis Of

APPLYING ANTHROPOLOGY TO FANTASY: A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE LORD OF THE RINGS By Christina C. Estep B.A., University of Mary Washington, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 © 2014 Christina C. Estep The thesis of Christina C. Estep is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ Margaret W. Huber, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Kristina Killgrove, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ John E. Worth, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Robert C. Philen, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ John R. Bratten, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to recognize my thesis committee, Dr. Robert Philen, Dr. Kristina Killgrove, Dr. John Worth, and Dr. Margaret Huber, for taking the time and effort to help me with not only my thesis, but my academic endeavors. Without these individuals, I would not be where I am now or possess the knowledge that I now have. Secondly, I want thank my parents, Bonnie and Carl Estep. Despite their hardships in life, my parents have supported me through every decision I have made, encouraged me to pursue a higher degree, and were always there to cheer me on when times were tough. Finally, I want to acknowledge my husband Brian, who has been my rock during the most stressful of times. -

Med20 Character Creation Rules

MIDDLE -EARTH D20 CHARACTER CREATION RULES To create characters for this campaign, o +4 racial bonus on any Craft skill of the players will use 25 points to purchase abilities player's choice — it should be noted that according to the Purchase rules on pages 15-16 Ñoldor were legendary for their work with of the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Core precious metals and jewelry. Rulebook . Then, character creation proceeds as o +2 racial bonus on any Perform (Sing) described in the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game checks. Core Rulebook . Additionally, players will create o +2 racial bonus on saves vs. fire. a 2 nd -level character, but the 1 st -level must be a o +2 racial bonus on saves vs. poison. basic NPC class ! Players may use the Pathfinder o Immune to Aging: Ñoldor Elves are Roleplaying Game Advanced Player’s Guide , immortal unless killed. Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Ultimate Combat , o Ñoldor Elves do not sleep, meditating and Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Ultimate Magic instead for about three hours every day. to create their characters. For all sources, use o Immune to natural cold. the following rules modifications. In addition, o Immune to disease, mundane or magical. the Variant Rules for Armor as Damage o Immune to scarring. Reduction, Called Shots, Piecemeal Armor, o Movement unimpeded by snow or wooded and Wounds and Vigor from Pathfinder terrain. Roleplaying Game Ultimate Combat (pp. 191-207) o Immune to any fear effects caused by are being utilized. Please note that these rules undead. are subject to change at any time without prior o Cannot be turned into undead. -

Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1992 Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hillis, Lisa, "Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings" (1992). Masters Theses. 2182. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2182 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for i,\1.clusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for iqclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Ef\i.stern Illinois University not allow my thes~s be reproduced because --------------- Date Author m Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings (TITLE) BY Lisa Hillis THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DECREE OF Master .of Arts 11': THE GRADUATE SCHOOL.