Free Extract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

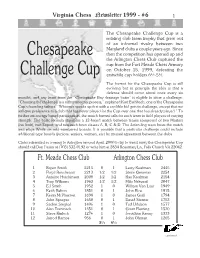

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Chess Strategy, by Edward Lasker #2 in Our Series by Edward Lasker

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Chess Strategy, by Edward Lasker #2 in our series by Edward Lasker Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Chess Strategy Author: Edward Lasker translated by J. Du Mont Release Date: May, 2004 [EBook #5614] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on July 22, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHESS STRATEGY *** Produced by John Mamoun <[email protected]>, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreaders website. INFORMATION ABOUT THIS E-TEXT EDITION The following is an e-text of "Chess Strategy," second edition, (1915) by Edward Lasker, translated by J. Du Mont. This e-text contains the 167 chess and checkers board game diagrams appearing in the original book, all in the form of ASCII line drawings. -

Do First Mover Advantages Exist in Competitive Board Games: the Importance of Zugzwang

DO FIRST MOVER ADVANTAGES EXIST IN COMPETITIVE BOARD GAMES: THE IMPORTANCE OF ZUGZWANG Douglas L. Micklich Illinois State University [email protected] ABSTRACT to the other player(s) in the game (Zagal, et.al., 2006) Examples of such games are chess and Connect-Four. The players try to The ability to move first in competitive games is thought to be secure some sort of first-mover advantage in trying to attain the sole determinant on who wins the game. This study attempts some advantage of position from which a lethal attack can be to show other factors which contribute and have a non-linear mounted. The ability to move first in competitive board games effect on the game’s outcome. These factors, although shown to has thought to have resulted more often in a situation where that be not statistically significant, because of their non-linear player, the one moving first, being victorious. The person relationship have some positive correlations to helping moving first will normally try to take control from the outset and determine the winner of the game. force their opponent into making moves that they would not otherwise have made. This is a strategy which Allis refers to as “Zugzwang”, which is the principle of having to play a move INTRODUCTION one would rather not. To be able to ensure that victory through a gained advantage In Allis’s paper “A Knowledge-Based Approach of is attained, a position must first be determined. SunTzu in the Connect-Four: The Game is Solved: White Wins”, the author “Art of War” described position in this manner: “this position, a states that the player of the black pieces can follow strategic strategic position (hsing), is defined as ‘one that creates a rules by which they can at least draw the game provided that the situation where we can use ‘the individual whole to attack our player of the red pieces does not start in the middle column (the rival’s) one, and many to strike a few’ – that is, to win the (Allis, 1992). -

Germany from Luther to Bismarck

University of California at San Diego HIEU 132 GERMANY FROM LUTHER TO BISMARCK Fall quarter 2009 #658659 Class meets Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2 until 3:20 in Warren Lecture Hall 2111 Professor Deborah Hertz Humanities and Social Science Building 6024 534 5501 Readers of the papers and examinations: Ms Monique Wiesmueller, [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 1:30 to 3 and by appointment CONTACTING THE PROFESSOR Please do not contact me by e-mail, but instead speak to me before or after class or on the phone during my office hour. I check the mailbox inside of our web site regularly. In an emergency you may contact the assistant to the Judaic Studies Program, Ms. Dorothy Wagoner at [email protected]; 534 4551. CLASSROOM ETIQUETTE. Please do not eat in class, drinks are acceptable. Please note that you should have your laptops, cell phones, and any other devices turned off during class. Students do too much multi-tasking for 1 the instructor to monitor. Try the simple beauty of a notebook and a pen. If so many students did not shop during class, you could enjoy the privilege of taking notes on your laptops. Power point presentations in class are a gift to those who attend and will not be available on the class web site. Attendance is not taken in class. Come to learn and to discuss. Class texts: All of the texts have been ordered with Groundworks Books in the Old Student Center and have been placed on Library Reserve. We have a systematic problem that Triton Link does not list the Groundworks booklists, but privileges the Price Center Bookstore. -

Grandmaster Opening Preparation Jaan Ehlvest

Grandmaster Opening Preparation By Jaan Ehlvest Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Preface This book is about my thoughts concerning opening preparation. It is not a strict manual; instead it follows my personal experience on the subject of openings. There are many opening theory manuals available in the market with deep computer analysis – but the human part of the process is missing. This book aims to fill this gap. I tried to present the material which influenced me the most in my chess career. This is why a large chapter on the Isolated Queen’s Pawn is present. These types of opening positions boosted my chess understanding and helped me advance to the top. My method of explaining the evolution in thinking about the IQP is to trace the history of games with the Tarrasch Defence, from Siegbert Tarrasch himself to Garry Kasparov. The recommended theory moves may have changed in the 21st century, but there are many positional ideas that can best be understood by studying “ancient” games. Some readers may find this book answers their questions about which openings to play, how to properly use computer evaluations, and so on. However, the aim of this book is not to give readymade answers – I will not ask you to memorize that on move 23 of a certain line you must play ¤d5. In chess, the ability to analyse and arrive at the right conclusions yourself is the most valuable skill. I hope that every chess player and coach who reads this book will develop his or her understanding of opening preparation. -

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 Pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1OiqRxa http://goo.gl/RTzNX http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=My+Best+Games+of+Chess%2C+1908-1937 One of chess's great inventive geniuses presents his 220 best games, with fascinating personal accounts of the dazzling victories that made him a legend. Includes historic matches against Capablanca, Euwe, and Bogoljubov. Alekhine's penetrating commentary on strategy, tactics, and more — and a revealing memoir. Numerous diagrams. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/6HPUQSukXD http://ebookbrowsee.net/bv/My-Best-Games-of-Chess-1908-1937 http://bit.ly/1haFYcA Games played in the world's Championship match between Alexander Alekhin (holder of the title) and E. D. Bogoljubow (challenger) , Frederick Dewhurst Yates, Alexander Alekhine, Efim Dmitrievich Bogoljubow, W. Winter, 1930, World Chess Championship, 48 pages. Championship chess , Philip Walsingham Sergeant, Jan 1, 1963, Games, 257 pages. Alexander Alekhine's Best Games , Alexander Alekhine, Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander, John Nunn, 1996, Games, 302 pages. This guide features Alekhine's annotations of his own games. It examines games that span his career from his early encounters with Lasker, Tarrasch and Rubenstein, through his. From My Games, 1920-1937 , Max Euwe, 1939, Chess, 232 pages. Masters of the chess board , Richard Réti, 1958, Games, 211 pages. The book of the Nottingham International Chess Tournament 10th to 28th August, 1936. Containing all the games in the Master's Tournament and a small selection of games from the Minor Tournament with annotations and analysis by Dr. -

Emanuel Lasker 2Nd Classical World Champ from 1894-1921

Emanuel Lasker 2nd classical world champ from 1894-1921 Emanuel Lasker, (born December 24, 1868, Berlinchen, Prussia [now Barlinek, Poland]— died January 11, 1941, New York, New York, U.S.), Emanuel Lasker was a German chess player, mathematician, and philosopher who was World Chess Champion for 27 years, from 1894 to 1921, the longest reign of any officially recognised World Chess Champion in history. Lasker, the son of a Jewish cantor, first left Prussia in 1889 and only five years later won the world chess championship from Wilhelm Steinitz. He went on to a series of stunning wins in tournaments at St. Petersburg, Nürnberg, London, and Paris before concentrating on his education. In 1902 he received his doctorate in mathematics from the University of Erlangen- Nürnberg, Germany. In 1904 Lasker resumed his chess career, publishing a magazine, Lasker’s Chess Magazine, for four years and winning against the top masters. He continued to play successfully through 1925, when he retired. He was forced out of retirement, however, after Nazi Germany confiscated his property in 1933. Fleeing first to England, then to the U.S.S.R., and finally to the U.S., he returned to tournament play, where he again competed at the highest levels, a rare achievement for his age. Lasker changed the nature of chess not in its strategy but in its economic base. He became the first chess master to demand high fees and thus paved the way to strengthening the financial status of professional chess players. He invented new endgame theories and then retired for some years to study philosophy and to teach and write. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

October, 1950 Scene from Dubrovnik 50 Cents

SCENE FROM DUBROVNIK SITE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CHESS TEAM TOURNAMENT (See Paye 290) OCTOBER, 1950 • ONE YEAR SUBSCRIPTION-$4.75 • 50 CENTS Emanuel Lasker won the World's Championship at the age of 26? Moving one square at a time, a Bishop may go from K 1 to K7 In eight moves in 483 ways ? In successive rounds, Reuben Fine once beat Botvinnik, Reshevsky, drew with Capablanca, beat Euwe, Flohr and Alekhine7 It t akes a Kn ight three moyes to checl!: a King that is two squares away on the same diagonal? WHITE is to play and draw in tllis ex· 12 B-R2 P- QR4 14 N_N1 P-B4 PaUl Morphy, King of Chess, alice lost qUisite ending by Korteling. 13 0 - 0 P-N5 15 B_B4 P-K5 a game in 12 moves? 16 N_N5 B-R3 Two lone Knights Cnnllot force mate ? mack cbaHenges White's best·posted Chess players fOl' mOl'e thun 500 years piece. used a pair of dice t o detet'mine their 17 BxB R,B 19 R,R N,R moves? 18 PxP RPxP 20 P-QB3 P-R3 21 N-R3 N-N5 Whimsy Now he attacks the Rook Pawn and Let us turn to a bit of Fail')' Chess , In fOl'ces 22 P-KK3, this problem by your columnist, the Call' 22 P_KN3 ventions are suspended, Black is to play And no\\", with all his Pawns on black first and he lp White to mate in three ::;ql1ll1'CS, White lias condemned his msll· moves. op to life imprisonmflnt, 22 ... -

CAPABLANCA Leyenda Y Realidad Tomo I

CAPABLANCA Leyenda y realidad Tomo I. El rey coronado MIGUEL ÁNGEL SÁNCHEZ “This book was originally published in English as José Raúl Capablanca: A Chess Biography by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. McFarland controls all rights for José Raúl Capablanca: A Chess Biography, excluding Spanish language rights. Non Spanish language inquiries should be mate to Rights and Permissions, McFarland, Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. USA”. Edición: Pablo de Cuba Soria © Logotipo de la editorial: Umberto Peña © Miguel Ángel Sánchez, 2019 © Del prólogo: Gustavo Pérez Firmat, 2019 Sobre la presente edición: © Casa Vacía, 2019 www.editorialcasavacia.com [email protected] Richmond, Virginia Impreso en USA © Todos los derechos reservados. Bajo las sanciones que establece la ley, queda rigurosamente prohibida, sin la autorización escrita del autor o de la editorial, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por ningún medio, ya sea electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo fotocopias o distribución en Internet. José Raúl Capablanca, por el fotógrafo Benjamin J. Falk “Es imposible comprender el mundo del ajedrez sin mirarlo con los ojos de Capablanca”. Mijaíl Botvinnik 1. El dorado del ajedrez Así comenzó la leyenda de Capablanca. En reposo sus calderas y casi al pairo mientras se diluía el espumante rastro de sus hélices, el City of Washington aguardaba el arribo de un prácti- co que lo condujera a través de arrecifes y corrientes por la angosta entrada de la bahía. Arrebujados en cubierta y batidos por el frío aire del mar, los pasaje- ros observaban a lo lejos la silueta del Castillo del Morro, la fortaleza que guarda la capital de la mayor isla del Mar Caribe.