History-Of-Linguistics-2005.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

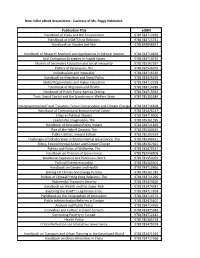

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

53 MEL-BULLETIN-53 Eng

MEL BULLETIN 53 PROPOSALS FOR CATECHETICAL RENEWAL MEL BULLETIN N. 53 - December 2018 Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools Secretariat for Association and Mission Editor: Br. Nestor Anaya, FSC [email protected] Editorial Coordinators: Mrs. Ilaria Iadeluca - Br. Alexánder González, FSC [email protected] Service of Communications and Technology Generalate, Rome, Italy MEL BULLETIN 53 PROPOSALS FOR CATECHETICAL RENEWAL BROTHER ENRIQUE GARCÍA AHUMADA, FSC* 2018 * [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 8 CHAPTER I The SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL AND POST-CONCILIAR CATECheTICAL TEAChiNG 1.1. Basic Documents 11 1.2. The Mission of the Church is to Evangelize in order to Extend the Kingdom of God 12 1.3. Evangelizing Involves Four Stages 12 1.3.1. The Missionary Stage Prepares the First Christian Announcement 12 1.3.2. The Second Stage is a Brief proclamation of the Good News Calling for Conversion 14 1.3.3. Given Christian Kerygma, the Third Stage of Evangelization is Catechesis 18 1.3.3.1. The RCIA Indicates Three Liturgical Steps to Grow in Holiness 20 1.3.3.2. The Catechumenate is a Model of Initiation into the Christian Life 23 1.3.4. The Fourth Stage: Formation of the Community or Incorporation into the already existing one 25 1.3.4.1. Mystagogy 26 1.4. The Council Focuses the Ministry of the Word on the Bible and Tradition 30 4 1.4.1. Faith is a Response to the Revelation or Word of God 31 1.4.2. Prayer is Basically a Dialogue with the Word of God 31 1.4.3. -

BOOKS from the LIBRARY of the EARLS of MACCLESFIELD

BOOKS from the LIBRARY of THE EARLS OF MACCLESFIELD CATALOGUE 1440 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Books from the Library of The Earls of Macclesfield Item 14, Artemidorus [4to]. Item 111, Hexham [folio]. CATALOGUE 1440 MAGGS BROS. LTD. 2010 Item 195, Schreyer [8vo]. Item 211, del Torre [4to]. Front cover illustration: The arms of the first Earl of Macclesfield taken from an armorial head-piece to the dedication of Xenophon Cyropaedia ed. T. Hutchinson, Oxford, 1727. BOOKS FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE EARLS OF MACCLESFIELD AT SHIRBURN CASTLE This selection of 240 items from the Macclesfield of languages. The works are almost all new to the Library formerly at Shirburn Castle near Watlington, market, Maggs having been privileged to have MAGGS BROS LTD Oxfordshire, mirrors the multiform interests of the received the remainder of the library not previously 50 Berkeley Square library, encompassing classical texts, works on the consigned for sale. The books, which are mostly non- military arts, a (very) few works of a scientific nature, English, range from one very uncommon incunable London W1J 5BA works of more modern literature and history, some to a few printed in the eighteenth century, but most collections of emblems, and some items on the study are of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Telephone 020 7493 7160 Fax 020 7499 2007 5 Email [email protected] 1 ABARBANEL, Isaac. Don Yitzhaq with loss of page numbers, modern half calf. [email protected] Abravani’el... & R. Mosis Alschechi Venice: M.A. Barboni, 1690 £2000 comment. in Esaiae prophetiam 30 [actually This work, clearly meant for those members of the Isaiah 52 v. -

Nóra Fodor DIE ÜBERSETZUNGEN LATEINISCHER AUTOREN DURCH M. PLANUDES

Nóra Fodor DIE ÜBERSETZUNGEN LATEINISCHER AUTOREN DURCH M. PLANUDES 4 VORWORT Beim Abschluss dieser Arbeit gilt mein Gedenken an erster Stelle Herrn Prof. Hubert Petersmann, der mich im Jahre 2000 als Doktorandin annahm und die ersten Arbeitsschritte begleitete. Als die Arbeit durch seinen tragischen Tod verwaiste, übernahm sie zuerst Prof. Angelos Chaniotis, später dann als Erstgutachterin Frau Prof. Catherine Trümpy, deren intensive Betreuung ich dankbar in Erinnerung behalte. Ich möchte auch PD Karin Metzler danken, die mich in byzantinischen Fragen beriet und auch das Druckmanuskript gelesen hat. Herr Prof. Géza Alföldy und Herr Prof. Miklós Maróth begleiteten die Fortschritte der Arbeit von Anfang an mit großem Wohlwollen und vielen hilfreichen Hinweisen. Auch in Heidelberg erfuhr ich mannigfaltige Unterstützung: Dankbar möchte ich Dr. Francisca Feraudi-Gruenais, Dr. Brigitte Ruck und Daniela Quade nennen. Während all der Jahre, die ich in Heidelberg an der Dissertation arbeitete, genoss ich die Unterstützung meiner Alma Mater, der Péter Pázmány Katholischen Universität, Budapest – Piliscsaba, nicht zuletzt aber gilt mein Dank den Institutionen, die die Arbeit finanziell unterstützten: der Graduierten Förderung der Karl Ruprecht Universität Heidelberg und der Magyar Ösztöndíj Bizottság (Eötvös József Kutatói Ösztöndíj im Jahre 2000 und Stipendium nach dem Landesgraduiertengesetz von 2001 bis 2003). Gewidmet sei diese Arbeit meiner Familie, der ich für ihre Förderung und Unterstützung zu grösstem Dank verpflichtet bin. 5 6 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. Einleitung . 11 1. Allgemeines und Zielsetzung . 11 2. Maximos Planudes – eine Kurzbiographie . 14 2. 1. Offizierskarriere - im kaiserlichen Scriptorium . 16 2. 2. Planudes: der Philologe und der Lehrer . 18 2. 3. Das Corpus der Übersetzungen des Planudes . 21 3. -

Reference Genres and Their Finding Devices," in Too

3 Reference Genres and Their Finding Devices The first new reference books to appear in print starting ca. 1500 were in- debted to ancient and medieval sources and models, but they also initiated a period of new experimentation and explosive growth in methods of information management. Printed compilations were larger than their medieval counterparts and often grew larger still in successive editions, while remaining commercially viable; reference books were steady sellers despite their considerable size and expense and despite being accessible only to the Latin- literate.1 The impressive size of many early modern reference books is a symptom of the same stockpiling mentality that motivated the large collections of reading notes. But while note- takers could rely on their memories to find their way around their notes, printed reference works needed to offer readers formalized finding devices with which to navigate materials they had not had a hand in preparing. These tools often came with instructions for use, which indicate that despite medieval precedents for some of them, readers of early printed books were not assumed to master them. For example, Conrad Gesner explained the reference function of his alphabeti- cally arranged natural history of animals in five volumes (Historia animalium, 1551): the “utility of lexica [like this] comes not from reading it from beginning to end, which would be more tedious than useful, but from consulting it from time to time [ut consulat ea per intervalla].”2 Here the classical Latin term consulere, usually applied to the consultation of people or oracles for advice, was applied to books; aware of introducing a new usage of the term Gesner added “per inter- valla” to make clear the intermittent and nonsequential nature of the reading he had in mind. -

Vieira's Eschatological Sources

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade de Lisboa: Repositório.UL Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Departamento de História Historical Interpretations of “Fifth Empire” - Dynamics of Periodization from Daniel to António Vieira, S.J. - Maria Ana Travassos Valdez DOCTORATE IN ANCIENT HISTORY 2008 Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Departamento de História Historical Interpretations of “Fifth Empire” - Dynamics of Periodization from Daniel to António Vieira, S.J. - Maria Ana Travassos Valdez Doctoral Dissertation in Ancient History, supervised by: Prof. Doctor José Augusto Ramos and Prof. Doctor John J. Collins 2008 Table of Contents Table of Figures.....................................................................................................................3 Resumo...................................................................................................................................4 Summary ................................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................8 Introduction .........................................................................................................................11 1) The Role of History in Christian Thought....................................................................... 14 a) The “End of Time”....................................................................................................................... -

Compendium of the Life, Virtues and Miracles and of the Official Records on the Cause of Canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Faithful Laywoman (1656-1680)

Compendium of the life, virtues and miracles and of the official records on the cause of canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Faithful Laywoman (1656-1680) from the archives of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Laywoman The Father Cardinals, the Patriarchs, the Archbishops, the Bishops and so many taking part in the coming Consistory will find in this Compendium the biographic profile of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, laywoman, as well as the principal phases of the Cause of beatification and of canonization and the Apostolic Letter of her beatification. I Life and Virtue Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, Indian virgin of the tribe of the Agniers or Mohawks, of the Iroquois Indians, spent the first part of her life in the territory now found in the State of New York, United States of America, and the rest in Canada where she died after a life of heroic virtue. Born in 1656 of a pagan Iroquois Indian man and of a devout Christian Algonquin woman, both of the Agniers Indian tribe, residing in Ossernenon (Auriesville) in the state of New York. The Indians of the tribe of the Blessed were the same ones who in the year 1642 had tortured and in 1646 sent to death St. Isaac Jogues. Her mother had received a good Christian education in the French colonies of Trois- Rivières in Canada, where, during the war between the Algonquins and the Agniers, she was captured by the latter and married to one of these. She preserved her faith to death and desired baptism for her children; however, before she could obtain for them sanctifying grace, there being no missionaries among the Agniers, she died in an influenza epidemic with her husband and son, leaving her little girl orphaned at age four. -

News Briefs Christopher Columbus Park Fall Festival

VOL. 120 - NO. 42 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, OCTOBER 14, 2016 $.35 A COPY Christopher Columbus Park News Briefs Fall Festival by Sal Giarratani According to President Obama According to President Obama, it’s all her fault. Obama says he’s not to blame for the rise of Trump. According to him it is all Sarah Palin’s fault. I kid you not. He unloaded this gem in an interview with New York Magazine. Says Obama, “I see a straight line from the announcement of Sarah Palin as the vice presiden- tial nominee to what we see today in Donald Trump.” Thank God that January 20th keeps getting closer all the time. My head has been hurting nearly eight years now. Kaine Wasn’t Able Because ... Why? There he was on late night TV a few days following his horrible act during the vice presidential debate. He was blaming all his antics on the fact he was, after-all, an Irish-American. As someone with two grandparents from West Cork, I am not buying his malarkey. He was acting like an ignorant and pretentious A(deleted). Don’t blame it on your heritage, blame it on you. His performance on stage was so outrageous that it was beyond the pale. Hillary also added post-debate that Tim Kaine looked like Lincoln and Churchill up there with Mike Pence. My God, perhaps she needs medicine too. Stop and Frisk not Unconstitutional “Get your facts fi rst, then you can distort them as (Photo by Rosario Scabin, Ross Photography) you please.” The annual Columbus Park Fall Festival featured all sorts of fun for neighborhood kids, complete — Mark Twain with a parade around the park and hours of free entertainment. -

Read a Sample

Our iņ ev Saints for Every Day Volume 1 January to June Written by the Daughters of St. Paul Edited by Sister Allison Gliot Illustrated by Tim Foley Boston 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 3 12/22/20 4:45 PM Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943471 CIP data is available. ISBN 10: 0– 8198– 5521– 9 ISBN 13: 978– 0- 8198– 5521– 3 The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Re- vised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover and interior design by Mary Joseph Peterson, FSP Cover art and illustrations by Tim Foley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. “P” and PAULINE are registered trademarks of the Daughters of St. Paul. Copyright © 2021, Daughters of St. Paul Published by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130– 3491 Printed in the USA OFIH1 VSAUSAPEOILL11-1210169 5521-9 www.pauline.org Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 25 24 23 22 21 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 4 12/14/20 4:12 PM We would like to dedicate this book to our dear Sister Susan Helen Wallace, FSP (1940– 2013), author of the first edition of Saints for Young Readers for Every Day. -

The Jesuits in Jamaica

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1942 The Jesuits in Jamaica Kathryn Wirtenberger Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Wirtenberger, Kathryn, "The Jesuits in Jamaica" (1942). Master's Theses. 426. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1942 Kathryn Wirtenberger THE JESUITS IN JA1v!AICA By Kathryn Wirtenberger A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University December 1942 Vita Kathryn Wirtenberger was born in Chicago, Illinois, January 31, 1906. She was graduated from Carl Schurz High School, Chicago, Illinois, January, 1922, and received a teachers certificate from Chicago Normal College, Chicago, Illinois, January, 1924. The Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in English was conferred by St. Mary's College, Notre Dame, Indiana, June, 1926. From 1935 to 1936 the writer studied at Oxford University, England and the London University. During the last three years the necessary graduate work has been taken at Loyola University. CONTENTS MAP OF JAMAICA, showing principal mission stations. INTRODUCTION: Purpose of thesis; historical background •• page 1 Chapter I. THE EARLIEST JESUITS IN JAMAICA............. -

JANUARY 2017 Indeed, Nothing Is to Be Preferred to the Work of God

JANUARY 1 JANUARY 2017 Indeed, nothing is to be preferred to the Work of God. (RB 43) 1 White* Sun. SOLEMNITY OF MARY, THE HOLY MOTHER OF GOD (OCTAVE DAY OF CHRISTMAS) OA. In Mass Gl, 3 readings no. 18 (Nm 6: 22-27; Ps 67: 2-3,5,6,8; Gal 4: 4-7; Lk 2:16-21), Cr, Pref of BVM I (on the Solemnity of the Motherhood), in Euch Pr I proper Celebrating the most sacred day…in communion... – 2d Vesp Votive Masses, Masses “for various needs and occasions,” and “daily” Masses for the dead are forbidden from 2 to 7 January, except as provided in nos. 374, 376 and 381 of the General Instruction (GIRM). The Second Week of the Psalter begins tomorrow in the Liturgy of the Hours. As regards the selection of Prefaces on Memorials, see the directions in the introduction, supra, page xvii. 2 White Mon. Basil the Great and Gregory Nazian-zen, Bishops, Doctors of the Church. Memorial. In Mass readings no. 205 (1Jn 2: 22-28; Ps 98: 1, 2-3, 3-4; Jn 1: 19-28), Pref of Pastors – Vesp of Memorial 3 White Tue after Octave of Christmas. Proper Mass, readings no. 206 (1Jn 2: 29 to 3: 6; Ps 98: 1, 3-4, 5-6; Jn 1: 29-34), Pref of the Nativity of the Lord – Vesper of weekday Or white Holy Name of Jesus. Opt Mem. In Mass readings no. 1206 (as supra), Pref of Holy Name (cf., Votive Mass) – Vesp of Memorial In Puerto Rico: As supra, or white or blue Our Lady of Bethlehem. -

Opus Christi Salvatoris Mundi

Opus Christi Salvatoris Mundi Newsletter Year 8 (2020) OPUS CHRISTI SALVATORIS MUNDI Issue 4 April 2020 MISSIONARY SERVANTS OF THE POOR Evangelisation Intention: We pray that those suffering from addiction may be helped and accompanied. (Intention of the Holy Father given through the Pope’s World Network of Prayer) The Splendor of the Truth 107. The inspired books teach the truth. Since The Cathechism of the Catholic Church therefore all that the inspired authors or sacred writers affirm should be regarded as SACRED SCRIPTURE II affirmed by the Holy Spirit, we must INSPIRATION AND TRUTH ON acknowledge that the books of Scripture SACRED SCRIPTURE firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, 105. God is the author of Sacred Scripture. The wished to see confided to the Sacred divinely revealed realitites, which are contained Scriptures» (DV 11). and presented in the text of Sacred Scripture, have been written down under the inspiration of 108. Still, the Christian faith is not a “religion of the the Holy Spirit. book.” Christianity is the religion of the “Word” For Holy Mother Church, relying on the faith of of God, a word which is “not a written and the apostolic age, accepts as sacred and mute word, but the Word which is incarnate canonical the books of the Old and the New and living.” (St. Bernard, S. missus est hom. Testaments, whole and entire, with all their 4,11:PL 183,86B). If Scriptures are not to parts, on the grounds that, written under the remain a dead letter, Christ, the eternal Word inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they have God as of the living God, must, through the Holy their author and have been handed on as such Spirit, “open [our] minds to understand the to the Church herself (DV 11).