53 MEL-BULLETIN-53 Eng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

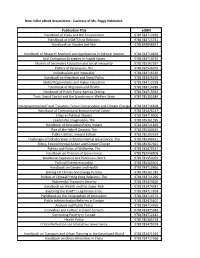

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Vieira's Eschatological Sources

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade de Lisboa: Repositório.UL Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Departamento de História Historical Interpretations of “Fifth Empire” - Dynamics of Periodization from Daniel to António Vieira, S.J. - Maria Ana Travassos Valdez DOCTORATE IN ANCIENT HISTORY 2008 Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Departamento de História Historical Interpretations of “Fifth Empire” - Dynamics of Periodization from Daniel to António Vieira, S.J. - Maria Ana Travassos Valdez Doctoral Dissertation in Ancient History, supervised by: Prof. Doctor José Augusto Ramos and Prof. Doctor John J. Collins 2008 Table of Contents Table of Figures.....................................................................................................................3 Resumo...................................................................................................................................4 Summary ................................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................8 Introduction .........................................................................................................................11 1) The Role of History in Christian Thought....................................................................... 14 a) The “End of Time”....................................................................................................................... -

Compendium of the Life, Virtues and Miracles and of the Official Records on the Cause of Canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Faithful Laywoman (1656-1680)

Compendium of the life, virtues and miracles and of the official records on the cause of canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Faithful Laywoman (1656-1680) from the archives of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Laywoman The Father Cardinals, the Patriarchs, the Archbishops, the Bishops and so many taking part in the coming Consistory will find in this Compendium the biographic profile of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, laywoman, as well as the principal phases of the Cause of beatification and of canonization and the Apostolic Letter of her beatification. I Life and Virtue Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, Indian virgin of the tribe of the Agniers or Mohawks, of the Iroquois Indians, spent the first part of her life in the territory now found in the State of New York, United States of America, and the rest in Canada where she died after a life of heroic virtue. Born in 1656 of a pagan Iroquois Indian man and of a devout Christian Algonquin woman, both of the Agniers Indian tribe, residing in Ossernenon (Auriesville) in the state of New York. The Indians of the tribe of the Blessed were the same ones who in the year 1642 had tortured and in 1646 sent to death St. Isaac Jogues. Her mother had received a good Christian education in the French colonies of Trois- Rivières in Canada, where, during the war between the Algonquins and the Agniers, she was captured by the latter and married to one of these. She preserved her faith to death and desired baptism for her children; however, before she could obtain for them sanctifying grace, there being no missionaries among the Agniers, she died in an influenza epidemic with her husband and son, leaving her little girl orphaned at age four. -

News Briefs Christopher Columbus Park Fall Festival

VOL. 120 - NO. 42 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, OCTOBER 14, 2016 $.35 A COPY Christopher Columbus Park News Briefs Fall Festival by Sal Giarratani According to President Obama According to President Obama, it’s all her fault. Obama says he’s not to blame for the rise of Trump. According to him it is all Sarah Palin’s fault. I kid you not. He unloaded this gem in an interview with New York Magazine. Says Obama, “I see a straight line from the announcement of Sarah Palin as the vice presiden- tial nominee to what we see today in Donald Trump.” Thank God that January 20th keeps getting closer all the time. My head has been hurting nearly eight years now. Kaine Wasn’t Able Because ... Why? There he was on late night TV a few days following his horrible act during the vice presidential debate. He was blaming all his antics on the fact he was, after-all, an Irish-American. As someone with two grandparents from West Cork, I am not buying his malarkey. He was acting like an ignorant and pretentious A(deleted). Don’t blame it on your heritage, blame it on you. His performance on stage was so outrageous that it was beyond the pale. Hillary also added post-debate that Tim Kaine looked like Lincoln and Churchill up there with Mike Pence. My God, perhaps she needs medicine too. Stop and Frisk not Unconstitutional “Get your facts fi rst, then you can distort them as (Photo by Rosario Scabin, Ross Photography) you please.” The annual Columbus Park Fall Festival featured all sorts of fun for neighborhood kids, complete — Mark Twain with a parade around the park and hours of free entertainment. -

Read a Sample

Our iņ ev Saints for Every Day Volume 1 January to June Written by the Daughters of St. Paul Edited by Sister Allison Gliot Illustrated by Tim Foley Boston 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 3 12/22/20 4:45 PM Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943471 CIP data is available. ISBN 10: 0– 8198– 5521– 9 ISBN 13: 978– 0- 8198– 5521– 3 The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Re- vised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover and interior design by Mary Joseph Peterson, FSP Cover art and illustrations by Tim Foley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. “P” and PAULINE are registered trademarks of the Daughters of St. Paul. Copyright © 2021, Daughters of St. Paul Published by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130– 3491 Printed in the USA OFIH1 VSAUSAPEOILL11-1210169 5521-9 www.pauline.org Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 25 24 23 22 21 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 4 12/14/20 4:12 PM We would like to dedicate this book to our dear Sister Susan Helen Wallace, FSP (1940– 2013), author of the first edition of Saints for Young Readers for Every Day. -

The Jesuits in Jamaica

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1942 The Jesuits in Jamaica Kathryn Wirtenberger Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Wirtenberger, Kathryn, "The Jesuits in Jamaica" (1942). Master's Theses. 426. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1942 Kathryn Wirtenberger THE JESUITS IN JA1v!AICA By Kathryn Wirtenberger A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University December 1942 Vita Kathryn Wirtenberger was born in Chicago, Illinois, January 31, 1906. She was graduated from Carl Schurz High School, Chicago, Illinois, January, 1922, and received a teachers certificate from Chicago Normal College, Chicago, Illinois, January, 1924. The Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in English was conferred by St. Mary's College, Notre Dame, Indiana, June, 1926. From 1935 to 1936 the writer studied at Oxford University, England and the London University. During the last three years the necessary graduate work has been taken at Loyola University. CONTENTS MAP OF JAMAICA, showing principal mission stations. INTRODUCTION: Purpose of thesis; historical background •• page 1 Chapter I. THE EARLIEST JESUITS IN JAMAICA............. -

JANUARY 2017 Indeed, Nothing Is to Be Preferred to the Work of God

JANUARY 1 JANUARY 2017 Indeed, nothing is to be preferred to the Work of God. (RB 43) 1 White* Sun. SOLEMNITY OF MARY, THE HOLY MOTHER OF GOD (OCTAVE DAY OF CHRISTMAS) OA. In Mass Gl, 3 readings no. 18 (Nm 6: 22-27; Ps 67: 2-3,5,6,8; Gal 4: 4-7; Lk 2:16-21), Cr, Pref of BVM I (on the Solemnity of the Motherhood), in Euch Pr I proper Celebrating the most sacred day…in communion... – 2d Vesp Votive Masses, Masses “for various needs and occasions,” and “daily” Masses for the dead are forbidden from 2 to 7 January, except as provided in nos. 374, 376 and 381 of the General Instruction (GIRM). The Second Week of the Psalter begins tomorrow in the Liturgy of the Hours. As regards the selection of Prefaces on Memorials, see the directions in the introduction, supra, page xvii. 2 White Mon. Basil the Great and Gregory Nazian-zen, Bishops, Doctors of the Church. Memorial. In Mass readings no. 205 (1Jn 2: 22-28; Ps 98: 1, 2-3, 3-4; Jn 1: 19-28), Pref of Pastors – Vesp of Memorial 3 White Tue after Octave of Christmas. Proper Mass, readings no. 206 (1Jn 2: 29 to 3: 6; Ps 98: 1, 3-4, 5-6; Jn 1: 29-34), Pref of the Nativity of the Lord – Vesper of weekday Or white Holy Name of Jesus. Opt Mem. In Mass readings no. 1206 (as supra), Pref of Holy Name (cf., Votive Mass) – Vesp of Memorial In Puerto Rico: As supra, or white or blue Our Lady of Bethlehem. -

Opus Christi Salvatoris Mundi

Opus Christi Salvatoris Mundi Newsletter Year 8 (2020) OPUS CHRISTI SALVATORIS MUNDI Issue 4 April 2020 MISSIONARY SERVANTS OF THE POOR Evangelisation Intention: We pray that those suffering from addiction may be helped and accompanied. (Intention of the Holy Father given through the Pope’s World Network of Prayer) The Splendor of the Truth 107. The inspired books teach the truth. Since The Cathechism of the Catholic Church therefore all that the inspired authors or sacred writers affirm should be regarded as SACRED SCRIPTURE II affirmed by the Holy Spirit, we must INSPIRATION AND TRUTH ON acknowledge that the books of Scripture SACRED SCRIPTURE firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, 105. God is the author of Sacred Scripture. The wished to see confided to the Sacred divinely revealed realitites, which are contained Scriptures» (DV 11). and presented in the text of Sacred Scripture, have been written down under the inspiration of 108. Still, the Christian faith is not a “religion of the the Holy Spirit. book.” Christianity is the religion of the “Word” For Holy Mother Church, relying on the faith of of God, a word which is “not a written and the apostolic age, accepts as sacred and mute word, but the Word which is incarnate canonical the books of the Old and the New and living.” (St. Bernard, S. missus est hom. Testaments, whole and entire, with all their 4,11:PL 183,86B). If Scriptures are not to parts, on the grounds that, written under the remain a dead letter, Christ, the eternal Word inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they have God as of the living God, must, through the Holy their author and have been handed on as such Spirit, “open [our] minds to understand the to the Church herself (DV 11). -

JUNE 2015 Óscar Romero Beatified Noticias En Español, P

NORTH COAST CATHOLIC The newspaper of the Diocese of Santa Rosa • www.srdiocese.org • JUNE 2015 Óscar Romero Beatified Noticias en español, p. 19-20 (Savior of the World Square) under the Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo. The cause of Archbishop Romero, who was gunned down in March 1980 at the height of El Salvador’s civil war, had provoked some debate because of initial uncer- tainty as to whether he was killed out of contempt for the Catholic faith or for taking political positions against Salvadoran government and against the death squads that were operating in his country. As head of the San Salvador archdiocese from 1977 until his death, his preaching grew increasingly strident in defense of the country’s poor and oppressed. He was also suspected of having an affinity for so-called Liberation Theology, which many—including the Vatican—consider a Marxist take on Christianity and thus incompatible with Catholicism. Andrew Pacheco Ordained His former secretary, however, recently confirmed that the archbishop had no use for Liberation Theology. While a Transitional Deacon he met with its proponents and they left him their books, Santa Rosa—On Friday, June 5, at 7pm, Bishop Robert their ideas never swayed him. F. Vasa ordained Mr. Andrew Pacheco of Ukiah to the Pope Benedict reportedly “unblocked” the cause for transitional diaconate. beatification of the Salvadoran prelate, and Pope Francis Men who are to be ordained to the priesthood receive also indicated that he hoped the cause would advance ordination to the diaconate prior to the priesthood. These Bl. Óscar Romero quickly. -

The JESUIT Wayof Proceeding

JESUITSMARYLAND PROVINCE USA NORTHEAST PROVINCE • WINTER 2020 The JESUIT WAY of Proceeding Encountering Christ in all things NOR SA TH U E A D S N T A P R D O N V A I L N Y C R E A S M Very Rev. Robert Hussey, SJ Very Rev. John Cecero, SJ 7 Provincial, Maryland Province Provincial, USA Northeast Province FROM OUR PROVINCIALS Dear Friends, It is often difficult to narrow this cover letter to one page, and this is certainly true at this time as we enter a new year, a new decade, and soon a new USA East Province. So much has happened in 2019 to lead us to this historic moment, and so many exciting developments are on the horizon for 2020. Last year, the canonization process began for Fr. Pedro Arrupe, SJ, a former Superior General for the Society of Jesus who challenged Jesuits to be leaders in the service of faith and justice in the world. After extensive dialogue with fellow Jesuits and lay partners from around the globe, our current Father General, Arturo Sosa, SJ, promulgated four new Universal Apostolic Preferences that will guide our mission for the coming decade. These preferences include showing the way to God through the Spiritual Exercises; walking with the poor and those on the margins in a mission “What you of reconciliation and justice; accompanying young people in the creation of a hope- filled future; and collaborating in the care of the earth, our common home. These preferences represent points of inspiration for all future discernment about our lives are in love and ministries as Jesuits with our colleagues in mission. -

“CATHOLICOVID-19” Or QUO VADIS CATHOLICA ECCLESIA: the Pandemic Seen in the Catholic Institutional Field

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00114-2 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access “CATHOLICOVID-19” or QUO VADIS CATHOLICA ECCLESIA: the Pandemic Seen in the Catholic Institutional Field Emerson Sena da Silveira1,2 Received: 18 July 2020 /Accepted: 1 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The aim of this paper is to understand, in a panoramic way, the ideas that some organized groups of Catholicism have expressed about the pandemic of the new coronavirus. We shall take as material for analysis, the web official pages of the following segments: Conferência Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil (CNBB) [National Conference of Bishops of Brazil], Heralds of the Gospel and Catholic Charismatic Renewal (CCR), especially from the moment when the first case of the disease caused by the Sars-Cov-2 virus and the health-social-economic emergency were checked. Catholic beliefs about Covid-19 and related themes (restrictive measures, social inequalities) show an intense and internal conflict of values or worldviews and lead to inquiring about the incidences of Catholicism in the public sphere. The qualitative-exploratory hypothesis demonstrates that the ad- vancement of the new coronavirus has accentuated tension lines existing in the Catholic Church and indicates that there is an ongoing dispute between the various official segments about the correct intonation of the Catholic voice in Brazilian society. To raise responses to the proposed problem, the paper is based on a qualitative method, namely, partial review of the bibliographic productions of the religious studies and analytical mapping of the main official positions (editorials, speeches, notes, texts) proposed by the three Catholic segments aforementioned. -

Read a Sample

Our iņ ev Saints for Every Day Volume 1 January to June Written by the Daughters of St. Paul Edited by Sister Allison Gliot Illustrated by Tim Foley Boston 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 3 12/22/20 4:45 PM Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943471 CIP data is available. ISBN 10: 0– 8198– 5521– 9 ISBN 13: 978– 0- 8198– 5521– 3 The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Re- vised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover and interior design by Mary Joseph Peterson, FSP Cover art and illustrations by Tim Foley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. “P” and PAULINE are registered trademarks of the Daughters of St. Paul. Copyright © 2021, Daughters of St. Paul Published by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130– 3491 Printed in the USA OFIH1 VSAUSAPEOILL11-1210169 5521-9 www.pauline.org Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 25 24 23 22 21 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 4 12/14/20 4:12 PM We would like to dedicate this book to our dear Sister Susan Helen Wallace, FSP (1940– 2013), author of the first edition of Saints for Young Readers for Every Day.