A 'Different Class'?: Homophily and Heterophily in the Social Class Networks of Britpop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swervedriver Never Lose That Feeling Mp3, Flac, Wma

Swervedriver Never Lose That Feeling mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Never Lose That Feeling Country: UK Released: 1992 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock, Shoegaze MP3 version RAR size: 1123 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1535 mb WMA version RAR size: 1377 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 243 Other Formats: AC3 XM AA WMA DTS DMF ASF Tracklist Hide Credits A Never Lose That Feeling/Never Learn B1 Scrawl And Scream The Watchmakers Hands B2 Engineer – Philip AmesGuitar [Pedal Steel] – Patrick Arbruthnot* B3 Never Lose That Feeling Companies, etc. Distributed By – Pinnacle Phonographic Copyright (p) – Creation Records Copyright (c) – Creation Records Pressed By – MPO Published By – EMI Music Published By – EMI Songs Engineered At – Greenhouse Studio, London Mixed At – Matrix Studios Mixed At – Battery Studios, London Credits Mastered By – Porky Mixed By – Alan Moulder Producer, Engineer – Alan Moulder (tracks: A, B1, B3) Producer, Written-By, Arranged By – Swervedriver Saxophone – Stuart Dace* (tracks: A, B3) Notes Engineered at The Greenhouse Studios A, B1, and B3 Mixed at Matrix Studios B2 Mixed at Battery Studios Stuart Dace courtesy of Deep Joy Inc (Worldwide) Patrick Arbruthnot courtesy of The Rockingbirds and Heavenly A Creation Records Product Printed on centre labels: Made In France Printed on rear sleeve: Made in England ℗ & © 1992 Creation Records Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 017556 201206 Matrix / Runout (A side runout etched): CRE 120 T A1 IT'S A PORKY PRIME CUT. MPO IS THIS A COINCIDENCE OR WHAT? Matrix / Runout (B side runout etched): CRE 120 T B1 PORKY. MPO THE CHICKENS ARE DANCING. -

L&O Acts on Road and Sidewalk Repair Stabilization Fund

TONIGHT Mostly Cloudy. Low of 22. The WestfieldNews Search for The Westfield News Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The Westfield “IT’S EASY TO BE INDEPENDENT News WHEN YOU VE GOT MONEY ’ . “TIME IS THE ONLY Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns BUT TO BE INDEPENDENT WHEN WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT YOU HAVEN’ T GOT A TH ING — TONIGHT THAT’S AMBITIONTHE LORD.”’ S TEST.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK —Search MaH AforLI TheA JA WestfieldCKSON News Westfield350.comWestfield350.orgLow of 55. Thewww.thewestfieldnews.com WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHERVOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 centsCRITIC WITHOUT VOL.88TONIGHT NO. 64 MONDAY, MARCH 18, 2019 75AMBITION Cents .” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com L&OVOL. 86 NO. 151 acts on road TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 cents and sidewalk repair stabilization fund By AMY PORTER Correspondent WESTFIELD – The Legislative & Ordinance Committee took up several motions that have been before the City Council since March of last year. The first was to accept the fourth paragraph of Mass. General Law (MGL) Chapter 40 Section 5B, which William Onysk Andrew K. Surprise allows cities and towns to create one or Ward 6 City Ward 3 Annual St. Patrick’s Day Breakfast more special purpose stabilization Councilor Councilor Above, new Chamber members, Laurie DeBruin, John Richards, Phyl Phillips, Chris Thompson, funds. the new paragraph in the MGL, brought and Harlene Simmons attend the Greater Westfield Chamber of Commerce’s annual St. Patrick’s The second motion before the com- Day Breakfast. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

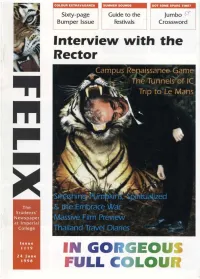

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

COLOUR EXTRAVAGANZA SUMMER SOUNDS GOT SOME SPARE TIME? Sixty-page Guide to the Jumbo $f Bumper Issue Festivals Crossword Interview with the Rector Campus Renaissance Game y the Tunnels "of IC 1 'I ^ Trip to Le Mans 7 ' W- & the Embrace War Massive Film Preview Thailand Travel Diaries IN GO EOUS FULL C 4 2 GAME 24 June 1998 24 June 1998 GAME 59 Automatic seating in Great Hall opens 1 9 18 unexpectedly during The Rector nicks your exam, killing fff parking space. Miss a go. Felix finds out that you bunged the builders to you're fc Rich old fo work Faster. "start small antiques shop. £2 million. Back one. ii : 1 1 John Foster electro- cutes himself while cutting IC Radio's JCR feed. Go »zzle all the Forward one. nove to the is. The End. P©r/-D®(aia@ You Bung folders to TTafeDts iMmk faster. 213 [?®0B[jafi®Drjfl 40 is (SoOOogj® gtssrjiBGariy tsm<s5xps@G(§tlI ITCD® esiDDorpo/Js Bs a DDD®<3CM?GII (SDB(Sorjaai„ (pAsasamG aracil f?QflrjTi@Gfi®OTjaD Y®E]'RS fifelaL rpDaecsS V®QO wafccs (MJDDD Haglfe G® sGairGo (SRBarjDDo GBa@to G® §GapG„ i You give the Sheffield building a face-lift, it still looks horrible. Conference Hey ho, miss a go. Office doesn't buy new flow furniture. ir failing Take an extra I. Move go. steps back. start Place one Infamou chunk of asbestos raer shopS<ee| player on this square, », roll a die, and try your Southsid luck at the CAMPUS £0.5 mil nuclear reactor ^ RENAISSANCE GAME ^ ill. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Britpop 1 a Free Quiz About the Music and the Musicians Associated with Britpop

Copyright © 2021 www.kensquiz.co.uk Britpop 1 A free quiz about the music and the musicians associated with Britpop. 1. Which journalist and DJ was credited for first using the term "Britpop" in 1993? 2. Which Oasis single provided them with their first UK number one in April 1995? 3. Gaz Coombes was the guitarist and lead singer of which 90s band? 4. The Verve's "Bittersweet Symphony" samples an orchestral version of which Rolling Stones hit? 5. Which Pulp album featured the single "Common People"? 6. Brett Anderson was the lead singer of which Britpop band? 7. What was the title of The Boo Radley's only UK top ten single? 8. In which northern city were Shed Seven formed in 1990? 9. Which song by Ocean Colour Scene was used by Chris Evans to introduce his guests on TFI Friday? 10. What was the original name of Britpop band Blur? 11. A founding member of Suede, which female fronted the band Elastica? 12. "Smart" was the debut album of which band? 13. Which band received the inaugural NME Brat Award for Best New Act in 1995? 14. Who sang alongside Space on their 1998 top five single "The Ballad of Tom Jones"? 15. Which single of 1991 gave Blur their first UK top ten hit? 16. Released in 1995, what was the title of Cast's debut album? 17. What was the name of the 90's band fronted by radio personality Laureen Laverne? 18. The 1996 single "Good Enough" was the only UK top ten hit for which band? 19. -

BIMM Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22

Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22 bimm.ac.uk Contents Welcome Welcome 3 As Principal of BIMM Institute Birmingham, I’m hugely excited to be at the helm of our newest UK college, About Birmingham 4 located at the heart of this vibrant creative and artistic My Birmingham 10 musical city. About BIMM Institute Birmingham 12 At BIMM Institute, we give you an experience of the real BIMM Institute Birmingham Lecturers 16 industry as it stands today – it’s our mission to create BIMM Institute Birmingham Courses 18 a microcosm of the music business within the walls of Location 22 the college. If you’re a songwriter, you’ll find the best musicians to collaborate with; if you’re a guitarist, bassist, Your City 24 drummer or vocalist, you’ll find the best songwriters and Music Resources 28 fellow band members. If you’re a Music Business, Music Production, Event Management or Music Marketing, Media Accommodation Guide 34 and Communication student, you’ll have access to the best Join Us in Birmingham 38 emerging musical talent the city has to offer. BIMM Institute is a hotbed of talent and being a BIMM student means you’ll be part of that community, making many vital connections, which you’ll hopefully keep for the rest of your life and career. The day you walk into BIMM Institute as a freshly enrolled student is the first day of your career. While you’re a BIMM student, you’ll be immersed in the industry. You’ll be taught by current music professionals who bring real, up-to-date experience directly into the classroom, and the curriculum they’re teaching is current and relevant because it constantly evolves with the latest developments in the business. -

Interview with Lush's Frontwoman Miki Berenyi

Interview with Lush's frontwoman Miki Berenyi musicophile97.blogspot.co.uk/2016/08/interview-with-lushs-frontwoman-miki.html It’s a regular Tuesday night in everything but the fact that I am currently sat opposite Miki Berenyi, the returned frontwoman of Lush. After nearly a 20-year break, the 90s favourite indie kids make their return. Much has changed for the band in the interim: Elastica’s Justin Welch replaces Chris Acland on drums after Acland committed suicide in 1996; Berenyi all but disappeared from the music scene to start a family and hold down a regular job. In spite of this, she remains the same at the core: she sips on white wine that she brought over, and intermittently takes a few drags on an e-cigarette. When she speaks of how it feels to be back, Berenyi says it’s ‘really quite odd actually […] I was losing sleep about having agreed to do this. I suddenly thought, “fuck, I haven’t played in twenty years, this is going to be a disaster.” And actually, it was really good to just go into the studio and sing and play guitar and think, “ok, I can still do this!”’ In spite of having been out of the game for so long, there is a clear sense of anticipation to play live again [I spoke to Berenyi before Lush’s headline shows at the Roundhouse]. ‘It’s a bit weird cos we haven’t played yet […] I went on the radio and they were like “ooh so how’s it going?” and all I can really talk about is rehearsals. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

Michael Bolton His Brandnewsinglecan 1Touch You...There? "Taken from the Forthcoming Columbia Release: Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995

MAKING WAVES: Ad Sales For Specialist Formats... see page 8 LUME 12, ISSUE 35 SEPTEMBER 2, 1995 Blur Is Highest New Entry In Eurochart £2.95 DM8 FFR25 US$5 DFL8.50 At No.7 Page 19 Armatrading Meets Mandela PopKomm Bigger Than Ever, Say Industry Insiders by Jeff Clark -Meads In his keynote speech at assuredness on the German PopKomm, ThomasStein, music scene." COLOGNE -The German music chairmanoftheGerman Stein, who is also president industry and the annual trade label's group BPW, stated, "We of BMG Ariola in the German- fair it hosts are growing in in the recorded music industry speaking territories, went on size and confi- are proud ofto say that Germany has now dence together, PopKomm. joined the ranks of the world's according to the That is most importantrepertoire leadersof the becausePop- sources (for detailed story, see country's record POP Komm has page 5). companies. now estab- PopKomm,heldinthe PopKomm, KOMM. lished itself as gigantic Cologne Congress held in Cologne the world's Centre, this year attracted 600 The high point of BMG artist Joan Armatrading's current world tour was from August 17- Die Hesse fiir biggest music exhibiting companies and her meeting with Nelson Mandela. One of her "dreams came true" when 20, is being trade fair and occupied 180.000 square feet she met him while in Pretoria to promote her latest album What's Inside. toutedasthe Popmusik andit takes place of exhibition space-twice as During a one-to-one meeting at his residence, Mandela signed a copy of world'sbiggest Entertainment in Germany. -

ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE of a RESILIENT SOUND in U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put on Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives a Billboard Staff Report

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) ZOb£-L0906 VO H3V38 9N01 V it 3AV W13 047L£ A1N331J9 A1NOW 5811 9Zt Z 005Z£0 100 lllnlririnnrlllnlnllnlnrinrllrinlrrrllrrlrll ZL9 0818 tZ00W3bL£339L080611 906 1I9I0-£ OIE1V taA0ONX8t THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT r MARCH 6, 1999 ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE OF A RESILIENT SOUND In U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put On Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives A Billboard staff report. with a host of newer acts being pulled A Billboard international staff Yoshida says. in their wake. report. As Yoshida and others look for NEW YORK -In a business in which Likewise, there is no one defining new rock -oriented talent, up -and- nothing breeds like success, "musical sound to be heard Often masquerading coming rock acts such as currently trends" can be born fast and fade among the pack, only as different sub-gen- unsigned three -piece Feed are set- faster. The powerful resurgence of the defining rock vibe res, no-nonsense rock ting the template for intelligent, rock bands in the U.S. market -a and a general feeling continues to thrive in powerful Japanese rock (Global phenomenon evident at retail and that it's OK to make key markets. Music Pulse, Billboard, Feb. 6) with radio, on the charts, and at music noise again. "For the THE FLYS Here, Billboard cor- haunting art rock full of nuances. video outlets -does not fit the proto- last few years, it wasn't respondents take a Less restrained is thrashabilly trio typical mold, however, and shows no cool to say you were in a global sound -check of Guitar Wolf, whose crazed, over -the- signs of diminishing soon. -

THE BIRTH of HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard Rock

THE BIRTH OF HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard rock was born in spaces too small to contain it, birthed and midwifed by youths simultaneously exhilarated by the prospect of emergent new freedoms and frustrated by the slow pace of their development, and delivered with equipment which had never been designed for the tasks to which it was now applied. Hard rock was the sound of systems under stress, of energies raging against confnement and constriction, of forces which could not be contained, merely harnessed. It was defned only in retrospect, because at the time of its inception it did not even recognise itself. The musicians who played the frst ‘hard rock’ and the audiences who crowded into the small clubs and ballrooms of early 1960s Britain to hear them, thought they were playing something else entirely. In other words, hard rock was – like rock and roll itself – a historical accident. It began as an earnest attempt by British kids in the 1960s, most of whom were born in the 1940s and raised and acculturated in the 1950s, to play American music, drawing on blues, soul, R&B, jazz and frst-generation rock, but forced to reinvent both the music, and its world, in their own image, resulting in something entirely new. However, hard rock was neither an only child, nor born fully formed. It shared its playpen, and many of its toys, with siblings (some named at the time and others only in retrospect) like R&B, psychedelia, progressive rock, art-rock and folk-rock, and it emerged only gradually from the intoxicating stew of myriad infuences that formed the musical equivalent of primordial soup in the uniquely turbulent years of the second (technicolour!) half of the 1960s.