February 1978

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Texoma Water Management Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs)

Lake Texoma Water Management Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Q1: Why is Lake Texoma so low? A1: A combination of factors is contributing to the current lake level. Even though there was substantial rainfall last May-July, there has been very little precipitation since. We need to have significant rainfall across the entire watershed that feeds Lake Texoma to bring water levels back up. In general, a persistent exceptional drought for the last three years has gripped much of the Lake Texoma watershed. Inflows into the lake for 2011 were the lowest since its construction and 2013 saw the second lowest inflows. Evaporation of water is also a contributing factor. On an average year, Lake Texoma loses approximately six feet (74”) of water to evaporation. When the Lake Texoma basin does not get enough rain, the combination of evaporation and ongoing water usage will cause the lake level to drop. The primary ongoing water usage from Lake Texoma is for municipal/ industrial water supply and hydropower, which are critical in meeting needs for water and electricity. The lake is designed and required to allow authorized project purposes such as water supply and hydropower to continue during drought periods. By this design, Texoma has historically maintained an elevation of 612 or above, approximately 85 percent of the time. Q2: Why are there water releases from Denison Dam during drought? A2: The Flood Control Act passed by Congress in 1938 allowed for the construction of Denison Dam for the authorized purposes of flood control and hydropower production. Other authorized project purposes, such as water supply and recreation were added later. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Southwestern's Vegetation

One West Third Street Tulsa, OK 74103-3502 918-595-6600 www.swpa.gov Frequently Asked Questions – Lake Texoma Hydropower Generation April 3, 2014 Question. Why is Southwestern generating at Lake Texoma when the lake is so low? Answer. Southwestern is generating only a minimal amount to meet short-term peaking and critical power needs. The year 2013 marked the lowest generation year in the 70 year history of Lake Texoma and Denison Dam. The year 2011 was the second lowest. In fact, SWPA has been operating in drought mode since January 2011, generating only 25% of average. Since May 2012, generation has been even less, about 19% of average. Question. What gives Southwestern the right to generate at all? Answer. Southwestern is one of two project users which pay into the U.S. Treasury for water storage in Lake Texoma. The other is Municipal & Industrial (M&I) water supply. As an authorized user of the project with designated water storage, Southwestern has the right to use the water storage for which it has paid. That said, however, Southwestern and its customers have voluntarily reduced generation to save storage during the drought responsible for the low Lake Texoma elevations. Question. Who are Southwestern's customers at Denison? Answer. The entire output of the project is marketed to Rayburn Country Electric Cooperative and Tex-La Electric Cooperative, both of which are not-for-profit rural electric cooperatives serving electrical load mainly in the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region. Question. What is ERCOT? Answer. ERCOT is one of nine Independent System Operators (ISO) in the United States. -

Lake Texoma State Park Resource Management Plan Marshall County, Oklahoma

Lake Texoma State Park Resource Management Plan Marshall County, Oklahoma Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. 6/30/2017 Fatemeh (Tannaz) Soltani, Ph.D. Chang-Heng (Hank) Yang This page intentionally left blank. i Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the assistance of numerous individuals in the preparation of this Resource Management Plan (RMP). On behalf of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department’s Division of State Parks, staff members were extremely helpful in providing access to information and in sharing of their time. The essential staff providing assistance for the development of the RMP included Julie Roach, manager of Lake Texoma State Park. Assistance was also provided by Kris Marek, Doug Hawthorne, Don Schafer and Ron McWhirter – all from the Oklahoma City office of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Merle Cox, Regional Manager of the Southeastern Region of Oklahoma State Parks also attended these meetings and assisted throughout the project. This RMP supplements and updates an earlier document from 2009. Due to the events of the time, the 2009 RMP focused on other possible properties that could be considered for expansion and development within the Oklahoma State Park system. Given the events and circumstances present in 2017, this RMP focuses on the future of the properties remaining within the boundaries of the extant Lake Texoma State Park. The October 2016 kick-off meeting followed critical discussions between the Commissioners of the Land Office (CLO), OTRD, Pointe Vista, and other parties regarding properties formerly included in the original Lake Texoma State Park. Attending this kick-off meeting on behalf of Pointe Vista and Catfish Bay Marina was Ryan Chapman. -

Hunting Guide Lake Texoma

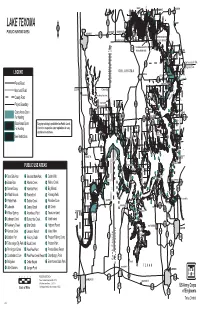

R 6 E RAVIA R 5 E MILBURN 6 1 6 TISHOMINGO R 5 E 1 R 4 E 4 13 78 7 11 7 11 12 9 R 7 E 12 R 6 E 12 . r C 13 14 18 15 d 177 18 n EMET 13 14 17 a S LAKE TEXOMA ig 20 N B 21 9919 PUBLIC HUNTING AREA DICKSON MANNSVILLE 19 24 ARDMORE 12 28 70 28 25 30 TISHOMINGO NATIONAL 25 26 30 . r WILDLIFE REFUGE C Johnston County 31 33 n e T 4 S P T 4 S T 5 S er TISHOMINGO WILDLIFE T 5 S 4 h c 1 4 3 2 1 t 70 MANAGEMENT AREA u NIDA B 11 y Cr. 22 ck 12 o BEE R 13 18 14 r. Johnston Co. s C 99 sa n 78 23 a 24 Bryan Co. 19 K OKLAHOMA 199 LEGEND MADILL 25 LITTLE CITY 29 Cr. 10 ow Moore Carter County Wid 199 31 32 36 Marshall County T 5 S Paved Road CUMBERLAND T 5 S T 6 S T 6 S 1 1 14 3 6 6 5 4 3 2 6 5 G R 6 E Improved Road Love County R 5 E l asses 12 11 12 7 7 OVERBROOK Lake Murray State Park 9 W 106 i 15 County Road l s o L Washita Arm itt n le 18 14 R 3 E R 2 E . G 15 C r la STATE GAME 14 C ss r E 4 R R 3 E E 3 R e . -

Download 2017-2022 Comprehensive

P a g e | 1 Prepared by the Texoma Council of Governments with assistance and funding from the Economic Development Administration (EDA), U.S. Department of Commerce P a g e | 2 Texoma Economic Development District Texoma Council of Governments Dr. Susan B. Thomas, Executive Director Staff: Deputy Executive Director Dr. Randy McBroom, GIS & Planning Program Manager Michael Schmitz, Economic Development Planner Nicole George Austin College Interns: Alison Boehmer, Juan Borda, Cody Derrick, Wes Nichols, Milo Opdahl Texoma Economic Development District CEDS Strategy Committee Terrence Steele, Texoma Workforce Solutions Gretchen Huff, Grayson College Monte Walker, Howe Economic Development Corporation Walter Menjivar, Local Business owner, La Placita, Sherman, TX Stephen J. Filipowicz, Executive Director, Bonham Economic Development Organization P a g e | 3 Texoma Economic Development District Governing Board Members President Honorable Jason Brinkley, County Judge, Cooke County Vice President Honorable Kevin Couch, Council Member City of Sherman Secretary/Treasurer Honorable Creta L. Carter II, County Judge, Fannin County Honorable Bob Thomas, Councilmember, City of Bonham Honorable Cliff Sicking, Cooke County Small City Representative, City of Muenster Honorable David Turner, Grayson County Small City Representative, City of Southmayd Honorable Jeff Whitmire, Commissioner, Precinct 01, Grayson County Honorable Jim Goldsworthy, Mayor, City of Gainesville Honorable Phyllis James, Community Representative, Grayson County Honorable Ronnie Bruce, -

Ground-Water Geology of Grayson County Texas

Ground-Water Geology of Grayson County Texas By E. T. BAKER, JR. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1646 Prepared in cooperation with the Texas Board of Water Engineers and the city of Sherman JNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1963 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows : Baker, Ernest T, 1931- Ground-water geology of Grayson County, Texas. Wash ington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1962. v. 61 p. maps, diagrs., tables. 24 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Water-supply paper 1646) Part of illustrative matter fold., part colored in pocket. Prepared in cooperation with the Texas Board of Water Engineers and the city of Sherman. Bibliography: p. 57-^58. 1. Water-supply Texas Grayson County. 2. Water, Underground Texas Grayson County. 3. Water Composition. I. Texas. Board of Water Engineers. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Introduction ______--__-__-____-_-____-__--_-___-_-____-----_------ 2 Location and extent of area _ __________________________________ 2 Purpose and scope of the investigation. _-_-____-_-___-_-_--_-__--. 3 Methods of investigation____-______-__-_______-_____-__-__----- 4 Economic development_________________________________-_-_____ 4 Previous investigations. ________________________________________ 6 Acknowledgments. ____________________________________________ 7 Physiography and drainage_-__________-_-_________-___--__-__-_ 7 Climate. ______ _ ____ _____ ______ _ __ ______ __ _____ 9 Geology-__----__------_--- --_---__-----_---------__--------_----_ 10 Geologic history. -

Bryan County Summer 2017

Oklahoma State Department of Health State of the County’s Health Report #HealthierOK Bryan County Summer 2017 Being healthy means optimizing all aspects of well-being, including physical, mental, and social well-being.1 Health is influenced by a variety of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors called ‘determinants of health’,2 such as our genetics, behaviors, where we live, and accessibility to health care. The determinants of health are inter-related, whereby changes in one determinant impact other determinants. As such, interventions and policies that target more than one determinant will have greater impact on our health.2 Oklahoma has historically ranked poorly in many key health indicators. The United Health Foundation ranked Oklahoma’s overall health in 2016 as 45th in the United States in their annual America’s Health Rankings report.3 Most of the indicators in the report relate to conditions that Oklahomans live with every day, such as poverty and limited access to primary care. The report cited Oklahoma’s high prevalence of smoking, uninsured, and premature death rate as some of the state’s biggest challenges. Such conditions, along with risky health behaviors like smoking and physical inactivity, contribute to the poor health status of Oklahomans. Recently, Oklahoma has experienced improvement in some key areas. Despite still having high prevalence of smoking, the rates have declined significantly over the past few years.4 The rate of teen births has declined 39% in 6 years,5 and the rate of infant deaths remains -

A GEOGRAPHIC STUDY of CHOCTAW COUNTY., OKLAHOMA Ii

i A GEOGRAPHIC STUDY OF CHOCTAW COUNTY., OKLAHOMA ii A GEOGRAPHIC STUDY OF CHOCTAW COUNTY, OKLAHOMA . ~.. ; I' By EDWIN GORDON PARDUE Bachelor of Science Southeastern State College ~·.,.... <~. Durant, Oklahoma 1943 Submitted to the Department of Geography Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1949 iii ., ., . ,,n 1 OKU HOMA ,,bHh-cLTUUL & MECIIANICAL C APPROVED BY: LillHARY MAY 10 1949 Chairman, Thesi·sL:lo'!!C;:.:o:::;;.mm~i ..... t..,.t-ee-- Head o he Department 231253 iv PREFACE From birth the author has lived on Marshall County farms varying from one-fourth to two miles in distance from the Red River and has lived along Boggy River and its vicinity since the building of the Denison Dam. While farming Boggy bottom for three years (sharing in one glorious yield and two crop failures) and teaching in the one-teacher schools of the area for five years, the author became very familiar with the hospitable people, their customs, habits, hardships, and problems. During the two years of boarding with Mr. Bill Trout, a retired cotton gin operator and owner, the author had the opportunity of hearing many con versations and comments on the changing economy of the county, particularly in cotton. Being able to see the present farming transition and hearing the old- timers speak of "What we used to do here" or "How the old land used to produce," the author became interested in a study of the county. By further study of the county, in relation to soils, people and natural resources of the surrounding area, the author is convinced the county has great possibilities for further development of the present trend if handled correctly. -

Bromide, Chloride, and Sulfate Concentrations, and Specific Conductance, Lake Texoma, Texas and Oklahoma, 2007–08

In cooperation with the City of Dallas Water Utilities Division Bromide, Chloride, and Sulfate Concentrations, and Specific Conductance, Lake Texoma, Texas and Oklahoma, 2007–08 Data Series 466 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front and back cover: Lake Texoma near Lake Texoma Dam near Denison, Texas (photograph by Dana A. Blanchette, U.S. Geological Survey). Bromide, Chloride, and Sulfate Concentrations, and Specific Conductance, Lake Texoma, Texas and Oklahoma, 2007–08 By Stanley Baldys III In cooperation with the City of Dallas Water Utilities Division Data Series 466 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 This and other USGS information products are available at http://store.usgs.gov/ U.S. Geological Survey Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 To learn about the USGS and its information products visit http://www.usgs.gov/ 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Baldys, Stanley, III, 2009, Bromide, chloride, and sulfate concentrations, and specific conductance, Lake Texoma, Texas and Oklahoma, 2007–08: U.S. Geological Survey Data -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Tulsa District

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Tulsa District Red River Valley Association COL Richard Pratt District Commander November 19, 2014 ® US Army Corps of Engineers BUILDINGUS Army Corps STRONG of Engineers® BUILDING STRONG® Tulsa District Reservoir Drought Update – 13 November 2014 Skiatook 698.0 - 56% Cons Pool (water supply/water quality) Heyburn Canton 759.8 - 65% Cons Pool 1602.1- 20% Cons Pool (water supply) (water supply for OKC only) Waurika 933.3– 31% Cons Pool Legend (water supply) Texoma - Drought Level I 610.4 – 64% Cons Pool - Drought Level II (water supply/hydro) - Drought Level III - Drought LevelUS Army IV Corps of Engineers BUILDING STRONG All Lakes are at Drought Level I and above 75% full unless® noted otherwise. Upper Red River . Current Lake Levels of the Upper Red River include: ► Lake Texoma – 64% Total System Conservation Storage Utilized = 52.1% ► Waurika Lake – 31% ► Altus – 9% ► Lake Kemp – 26% ► Fort Cobb – 67% ► Foss – 39% ► Tom Steed – 20% ► Arbuckle – 70% BUILDING STRONG® Tulsa District Drought Issue We are in a period of drought Manage effects using Lake Drought Management Plans Adhere to contractual agreements as dictated by law Opportunity Texoma (Level 2) – If elevation 607’ is reached, notify SWPA to revise generation from rapid Encourage conservation response, short term peaking purposes to critical power needs Communicate with the public Canton (Level 3) - Prepare for degrading water quality Take advantage of maintenance opportunities Waurika (Level 3) – Provide access to remaining water supply Minimize -

Red River - Denison Dam to Ark.-La

• ,: "':; Reach 5 - Red River - Denison Dam to Ark.-La. State Line a. ProDosal discu~sed 25 January 1965. "1. The States of Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas shall have the free and unrestricted use of the >Taters in that part of a tributary or subtributary of the Red River lyinS ~Iithin each respective State above any dam now constructed or nOH authorized for construction by the Federal Government in the respective State and on that tributary • oI""lrt@tlill>UUWY • (Note that restrictions, or agreements, to protect Federal projects are assumed to be set forth elsewhere in the Compact.) ';..:. ".: "2. Naintenance of a minimum flo\{ in Red River at the Arkansas-Louisiana State Line shall be provided for as necessary by . ' . .~~.;~,'~ releasing from the reservoirs in the P~d RiVer basin beloH Denison Dam, and including Lake Texoma, a total of not more than 200. cfs whenever the rate of flow at the Arkansas-Louisiana State Line is less than 1,000 cfs. The States of Arkansa:;, Ok l,,:iOma , and Texas shall De responsible for their proportion."}te sh .. n"c: c.f tbe releases on the following percentages of the flo,·, requ:[r'eroc'.1: of up to 200 cfs: Arkansas 19 ;~('!rcant Oklahoma 47 ~,(,rcent Texas 3'+ f,crcent "3. All \'latet'1S r,~lc,~scd or Sl)i.l:'cd on any tributary of :::::::::: the Red River below Denison Dam ::orom the mos": dOHnstream dam noW constructed or authorized for construc,ion by the Federal Government on that tributary and all Haters releesed or spilled from Lake Texoma, shall not be diverted before said water passes the -

Downstream Effects of Dams on Alluvial Rivers

Downstream Effects of Downstream Effects of Dams on Alluvial Rivers By GARNETT P. WILLIAMS and M. GORDON WOLMAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1286 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1984 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WILLIAM P. CLARK, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director First printing 1984 Second printing 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Garnett P. Downstream effects of dams on alluvial rivers. (Geological Survey Professional Paper; 1286) Includes bibliographical references. Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.16:1286 1. River channels. 2. Rivers Regulation. 3. Dams. I. Wolman, M. Gordon (Markley Gordon), 1924- II. Title. III. Title: Alluvial rivers. IV. Series. TC175.W48 1983 551.48'2 82-600318 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ......................... 1 Downstream effects of dams continued Introduction ....................... 1 Mean bed elevation Continued Scope of study ................... 1 Longitudinal-profile changes ............. 26 Study sites and selection criteria ......... 1 Bed material and degradation ................ 29 Acknowledgments .................. 2 Theoretical expectations ................. 29 Methods of analysis and data sources ......... 2 Variations in bed-material sizes with time at a cross sec Water discharge .................. 2 tion ........................... 29 Sediment load .................... 2 Variations in bed-material sizes with