Grayson County, Texas, in Depression and War: 1929‐1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Texoma Durant, Oklahoma ENTRY FEES PRE

BASSMASTER ELITE SERIES BASSfest – Lake Texoma Durant, Oklahoma ENTRY FEES MARSHAL ENTRY FEE$125 (paid at sign up) DEADLINE: May 10, 2015 Entry fees are non-refundable and non-transferable regardless of date of cancellation if you are in the tournament. Marshals on the waiting list for this tournament who do not get in will be refunded your entry fee within 6 weeks after the event. PRE TOURNAMENT INFORMATION REGISTRATION/CHECK-IN Tuesday, June 7, 2015 DATE/BRIEFING/FOCAS/SOCIAL 3735 Choctaw Rd. TUESDAY ACTIVITIES LOCATION Choctaw Casino Durant Durant, OK 74701 OFFICIAL MARSHAL ONSITE 3:00 pm to 4:00 pm REGISTRATION/CHECK-IN You must register in person with B.A.S.S. Staff. This will be the only registration period. OFFICIAL PRO LICENSE CHECK Pros will be pre-registered and licenses will be checked in as they enter briefing With Tournament Officials TOURNAMENT SOCIAL 4:45 pm to 5:30 pm TOURNAMENT PRO BRIEFING 4:30 pm All BASSfest pros must attend and be on time TOURNAMENT MARSHAL BRIEFING 4:15 pm to 4:45 pm All Bassmaster Marshals must attend and be on time FOCAS (Fellowship of Christian Anglers) Immediately following briefing OFFICIAL PRACTICE DAYS June 5, 6, 7, 2016 (Sunday, Monday and Tuesday) DATES TOURNAMENT WATERS Starts Monday May 9, 2016 until first practice day OFF-LIMITS FOR PROS (Read Rule No. 3 carefully regarding the “no information rule” during off-limits) DATES TOURNAMENT WATERS There are no off limits for Marshals OFF-LIMITS FOR MARSHALS Lake Texoma and all rivers (Red River and Washita River), creeks and canals connecting TOURNAMENT WATERS to Lake Texoma. -

Lake Texoma Water Management Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs)

Lake Texoma Water Management Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Q1: Why is Lake Texoma so low? A1: A combination of factors is contributing to the current lake level. Even though there was substantial rainfall last May-July, there has been very little precipitation since. We need to have significant rainfall across the entire watershed that feeds Lake Texoma to bring water levels back up. In general, a persistent exceptional drought for the last three years has gripped much of the Lake Texoma watershed. Inflows into the lake for 2011 were the lowest since its construction and 2013 saw the second lowest inflows. Evaporation of water is also a contributing factor. On an average year, Lake Texoma loses approximately six feet (74”) of water to evaporation. When the Lake Texoma basin does not get enough rain, the combination of evaporation and ongoing water usage will cause the lake level to drop. The primary ongoing water usage from Lake Texoma is for municipal/ industrial water supply and hydropower, which are critical in meeting needs for water and electricity. The lake is designed and required to allow authorized project purposes such as water supply and hydropower to continue during drought periods. By this design, Texoma has historically maintained an elevation of 612 or above, approximately 85 percent of the time. Q2: Why are there water releases from Denison Dam during drought? A2: The Flood Control Act passed by Congress in 1938 allowed for the construction of Denison Dam for the authorized purposes of flood control and hydropower production. Other authorized project purposes, such as water supply and recreation were added later. -

February 1978

s ESS February 1978 Business Doctorates in Texas 29 An Interview with Jess R. Totten 31 .......Denison: A Center for Diversified Light Manufacturing 34 Rousing Market Outlook: 1978 37 A Compari•on ot Foreign and Texas Labor Costs 40 Texas Vol. 52, No. 2, February 1978 Business Review 29 Business Doctorates in Texas: A Study in Demand and Supply, Barry Render, William Wagoner, James R. Bobo, Stephen Corliss Published by the Bureau of Business 31 An Interview with Jess R. Totten, Ken Roberts Research, University of Texas at Austin Charles C. Holt, Director 34 Sherman-Denison: A Center for Diversified Light Manufac Lorna Monti, Associate Director turing, Carol T.F. Bennett, Charles P. Zlatkovich 37 Housing Market Outlook: 1978, Charles H. Wurtzebach 40 A Comparison of Foreign and Texas Labor Costs: Implica The Authors tions for Foreign Direct Investment in Texas, Sion Barry Render Raveed, Tim Meinershagen, Robert B. Morris III Acting Director, Division of Business and Economic Research University of New Orleans Tables William Wagoner Professor of Economics University of New Orleans 29 Business Ph.D. Demand and Supply in Texas, 1977 through 1981 Jam es R. Bobo 30 Business Ph.D. Demand and Supply in the Southern Region, 1977 Dean of the Graduate School of Business through 1981 University of New Orleans 30 Sources of New Business Faculty for Texas Schools, 1974 through 1977 Stephen Corliss 35 Nonagricultural Civilian Payroll Employment Percentages, Sherman Graduate Research Assistant College of Business Denison SMSA and United States, July 1977 Administration 35 Percentage of Personal Income by Major Sources, 1975, Sherman University of New Orleans Denison SMSA and Texas Ken Roberts Research Associate 36 Manufacturing Plants with More Than 250 Employees, Sherman-Denison Bureau of Business Research SMSA, 1977 Carol T.F. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Southwestern's Vegetation

One West Third Street Tulsa, OK 74103-3502 918-595-6600 www.swpa.gov Frequently Asked Questions – Lake Texoma Hydropower Generation April 3, 2014 Question. Why is Southwestern generating at Lake Texoma when the lake is so low? Answer. Southwestern is generating only a minimal amount to meet short-term peaking and critical power needs. The year 2013 marked the lowest generation year in the 70 year history of Lake Texoma and Denison Dam. The year 2011 was the second lowest. In fact, SWPA has been operating in drought mode since January 2011, generating only 25% of average. Since May 2012, generation has been even less, about 19% of average. Question. What gives Southwestern the right to generate at all? Answer. Southwestern is one of two project users which pay into the U.S. Treasury for water storage in Lake Texoma. The other is Municipal & Industrial (M&I) water supply. As an authorized user of the project with designated water storage, Southwestern has the right to use the water storage for which it has paid. That said, however, Southwestern and its customers have voluntarily reduced generation to save storage during the drought responsible for the low Lake Texoma elevations. Question. Who are Southwestern's customers at Denison? Answer. The entire output of the project is marketed to Rayburn Country Electric Cooperative and Tex-La Electric Cooperative, both of which are not-for-profit rural electric cooperatives serving electrical load mainly in the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region. Question. What is ERCOT? Answer. ERCOT is one of nine Independent System Operators (ISO) in the United States. -

Lake Texoma State Park Resource Management Plan Marshall County, Oklahoma

Lake Texoma State Park Resource Management Plan Marshall County, Oklahoma Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. 6/30/2017 Fatemeh (Tannaz) Soltani, Ph.D. Chang-Heng (Hank) Yang This page intentionally left blank. i Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the assistance of numerous individuals in the preparation of this Resource Management Plan (RMP). On behalf of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department’s Division of State Parks, staff members were extremely helpful in providing access to information and in sharing of their time. The essential staff providing assistance for the development of the RMP included Julie Roach, manager of Lake Texoma State Park. Assistance was also provided by Kris Marek, Doug Hawthorne, Don Schafer and Ron McWhirter – all from the Oklahoma City office of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Merle Cox, Regional Manager of the Southeastern Region of Oklahoma State Parks also attended these meetings and assisted throughout the project. This RMP supplements and updates an earlier document from 2009. Due to the events of the time, the 2009 RMP focused on other possible properties that could be considered for expansion and development within the Oklahoma State Park system. Given the events and circumstances present in 2017, this RMP focuses on the future of the properties remaining within the boundaries of the extant Lake Texoma State Park. The October 2016 kick-off meeting followed critical discussions between the Commissioners of the Land Office (CLO), OTRD, Pointe Vista, and other parties regarding properties formerly included in the original Lake Texoma State Park. Attending this kick-off meeting on behalf of Pointe Vista and Catfish Bay Marina was Ryan Chapman. -

Quality of Water of Big Mineral Arm and Tributaries Lake Texoma

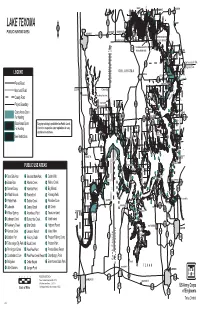

TEXAS WATE R DEVELOPMENT BOA RD REP 0 RT 35 QUALITY OF WATER OF BIG MINERAL ARM AND TRIBUTARI ES LAKE TEXOMA, TEXAS January 18-20 and February 10-11, 1966 NOVEMBER 19 6 6 TEXAS WATER DEVELOPMENT BOARD REPORT 35 QUALITY OF WATER OF BIG MINERAL ARM AND TRIBUTARIES LAKE TEXOMA, TEXAS J anuary 18-20 and February 10-11, 1966 By H. B. Mendieta and P . W. Skinner United States Geological Survey Prepared by the U.S. Ge ological Survey in cooperation with t he Texas Water Deve lopment Board a nd the City of Sherman Novembe r 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pa ge I NTRODUCTION. .••.. • .•••••.• • .•... •• • • .•.•••.••.• • •••....•.•.. .. • . •• . • 1 QUA LI TY OF WATER OF BIG MINERAL ARM .•.••.• • ••••••••••.••.••• •• .••...• . • 1 QUALITY OF WATER OF TRIBUTARIES TO BIG MINERAL ARM ............ ... ..... 6 CONCLUSIONS................. ...•.. ..•...... •...•.•••. ..•. ...•. 10 RECOMMENDATIONS. • ••••••••.••.•••.•.••.•...••.••.••••••..••...••..••••• 14 REFERE NCES CITED. ........................... ...................... ..... 16 TABLES 1. Di agrammatic table s howi ng depths , s pec i f i c conduc t ances, a nd ch lor i des in that or de r f or sampling s i t es i n Bi g Mineral Arm, January 20, 1966............. ................. ... ... 4 2 . Chemi cal ana lyses of water from Bi g Mi ne r al Arm and ma i n body of Lake Texoma , J anuary 20, 1966 . .. .. .. .. ...... .... .. 5 3 . Chemica l ana lyses of inflow water du r ing low and high f lows i nto Big Mine ral Arm, J an uary 18- 19 and February 10- 11, 1966............. ... ... ........... ............. .......... 8 ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1 . Map of Lake Texoma and Vi cinity Showing Location of Repo r t Area . -

Fishing and Boating Regulations Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Fishing and Boating Regulations Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge waters. This includes any type of y o gas or electric motor that is onboard and capable of use. We allow Fishing Boating launching only from L Pad Road or Fishing with hook and line is allowed on 1. Boating season begins March 15 and by hand at the Big Mineral Day designated areas of the refuge subject to extends through September 30. Use Area the following conditions: 2. Boats may be launched only at 9. At the point where Big Mineral 1. Bank and wade fishing are allowed designated boat ramps located Creek joins Lake Texoma, Big year-round in areas open for public between Pad A and Pad B roads, on Mineral Creek is a year-round fishing access. All refuge ponds are Tern Road, and on L Pad Road. Hand no-wake zone to the end of upstream closed from October 1 through launch sites are located at Big navigable waters. March 14. Mineral and Goode Day Use Areas. 2. You must possess a valid State of 3. All State and Federal regulations Texas or Lake Texoma fishing license apply to boats using the refuge. S while fishing in refuge waters. 4. Hazards: Big Mineral Arm contains General Regulations 1. The refuge opens at sunrise and 3. Use of any containers (jugs, bottles) floating debris. closes at sunset daily. as floats is not allowed. 5. Airboats, hovercraft, and personal 2. Fires are not allowed. 4. During the boating season, trotlines watercraft such as jet skis are not are allowed in the open area of the allowed on the refuge. -

Hunting Guide Lake Texoma

R 6 E RAVIA R 5 E MILBURN 6 1 6 TISHOMINGO R 5 E 1 R 4 E 4 13 78 7 11 7 11 12 9 R 7 E 12 R 6 E 12 . r C 13 14 18 15 d 177 18 n EMET 13 14 17 a S LAKE TEXOMA ig 20 N B 21 9919 PUBLIC HUNTING AREA DICKSON MANNSVILLE 19 24 ARDMORE 12 28 70 28 25 30 TISHOMINGO NATIONAL 25 26 30 . r WILDLIFE REFUGE C Johnston County 31 33 n e T 4 S P T 4 S T 5 S er TISHOMINGO WILDLIFE T 5 S 4 h c 1 4 3 2 1 t 70 MANAGEMENT AREA u NIDA B 11 y Cr. 22 ck 12 o BEE R 13 18 14 r. Johnston Co. s C 99 sa n 78 23 a 24 Bryan Co. 19 K OKLAHOMA 199 LEGEND MADILL 25 LITTLE CITY 29 Cr. 10 ow Moore Carter County Wid 199 31 32 36 Marshall County T 5 S Paved Road CUMBERLAND T 5 S T 6 S T 6 S 1 1 14 3 6 6 5 4 3 2 6 5 G R 6 E Improved Road Love County R 5 E l asses 12 11 12 7 7 OVERBROOK Lake Murray State Park 9 W 106 i 15 County Road l s o L Washita Arm itt n le 18 14 R 3 E R 2 E . G 15 C r la STATE GAME 14 C ss r E 4 R R 3 E E 3 R e . -

Download 2017-2022 Comprehensive

P a g e | 1 Prepared by the Texoma Council of Governments with assistance and funding from the Economic Development Administration (EDA), U.S. Department of Commerce P a g e | 2 Texoma Economic Development District Texoma Council of Governments Dr. Susan B. Thomas, Executive Director Staff: Deputy Executive Director Dr. Randy McBroom, GIS & Planning Program Manager Michael Schmitz, Economic Development Planner Nicole George Austin College Interns: Alison Boehmer, Juan Borda, Cody Derrick, Wes Nichols, Milo Opdahl Texoma Economic Development District CEDS Strategy Committee Terrence Steele, Texoma Workforce Solutions Gretchen Huff, Grayson College Monte Walker, Howe Economic Development Corporation Walter Menjivar, Local Business owner, La Placita, Sherman, TX Stephen J. Filipowicz, Executive Director, Bonham Economic Development Organization P a g e | 3 Texoma Economic Development District Governing Board Members President Honorable Jason Brinkley, County Judge, Cooke County Vice President Honorable Kevin Couch, Council Member City of Sherman Secretary/Treasurer Honorable Creta L. Carter II, County Judge, Fannin County Honorable Bob Thomas, Councilmember, City of Bonham Honorable Cliff Sicking, Cooke County Small City Representative, City of Muenster Honorable David Turner, Grayson County Small City Representative, City of Southmayd Honorable Jeff Whitmire, Commissioner, Precinct 01, Grayson County Honorable Jim Goldsworthy, Mayor, City of Gainesville Honorable Phyllis James, Community Representative, Grayson County Honorable Ronnie Bruce, -

Reconstruction in Collin County, Texas, 1865-1876

RECONSTRUCTION IN COLLIN COUNTY, TEXAS, 1865-1876 Jesse R. Thompson Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2015 APPROVED: Randolph B. Campbell, Committee Chair Gustav Seligmann, Committee Member Andrew Torget, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Thompson, Jesse R. Reconstruction in Collin County, Texas, 1865-1876. Master of Arts (History), August 2015, 59 pp., 5 tables, 3 figures, bibliography, 46 titles. This is a work of local history examining the course of Reconstruction in Collin County, Texas. National and state level surveys of Reconstruction often overlook the experiences of communities in favor of simpler, broader narratives. The work proceeds chronologically, beginning with the close of the Civil War, and tells the story of Collin County as national Reconstruction progressed and relies on works of professional and non---academic historians, oral histories, census data, and newspapers to present a coherent picture of local life, work, and politics. The results exemplify the value of local history, as local conditions influenced the course of events in Collin County as much as those in Austin and Washington D.C. The story of Reconstruction in Collin County is one of anomalous political views resulting from geographical exclusion from the cotton culture of Texas followed by a steady convergence. As Reconstruction progressed, Collin County began to show solidarity with more solidly conservative Texas Counties. The arrival of railroads allowed farmers to move from subsistence agriculture to cash crop production. This further altered local attitudes toward government, labor, voting rights, and education for Freedmen. By the end of Reconstruction, Collin County had all but abandoned their contrarian social and political views of the 1850s and 1860s in favor of limited rights for blacks and Redemption. -

View Finding

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Advertising of the West Collection Advertising of the West Collection. Printed material, 1874–2016. 2 feet. Subject collection. Promotional brochures, flyers, handbills, maps, and original illustrations advertising geographic locations in the American West, as well as using the image of the West to sell other goods and services. The materials advertise tourist destinations such as rodeos, ranches, and the Grand Canyon; promotional brochures for western cities and towns such as Deming, New Mexico, and Lander, Wyoming; illustrated mining company stock certificates; and illustrations by Ken Laager for the covers of various western novels. ________________________ Box 1 Folder: 1. Color tourist brochure for Scenic Airways, Inc., Arizona, “Fly Over the Colorful West.” Cover features illustration of a Ford tri-motor plane flying over the Grand Canyon. 2. Tourist brochure for California’s Oak Knoll Ranch, Melone Co., Napa, California. Black and white with green details; cover features a man astride a rearing horse. 3. Color advertising brochure, “Here’s the Inside Story of the 1938 Pontiac Silver Streak, America’s Finest Low-Price Car.” Cover features illustrated profile of American Indian chief Pontiac and the face of Uncle Sam on yellow background. Brochure opens to reveal 3 lifting tabs that show various exterior and interior views of the car and its construction. 4. Brady's Tourist Guide: Oklahoma. Official Road Information of Brady Map & Pub. Co. Inc., Oklahoma City, Okla., for North America, 1925. 5. Promotional map of Grand Lake and Spavinaw Lake of Oklahoma, published by The Northeast Oklahoma Lakes Association and The Miami Chamber of Commerce, n.d. -

Diplopoda: Platydesmida: Andrognathidae) from Oklahoma Chris T

42 A New Geographic Record for Brachycybe lecontii (Diplopoda: Platydesmida: Andrognathidae) from Oklahoma Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Matthew B. Connior Life Sciences, Northwest Arkansas Community College, One College Drive, Bentonville, AR 72712 ©2016 Oklahoma Academy of Science Much has been published on the millipeds of B. lecontii in the western part of its range (Diplopoda) of Oklahoma since the turn of the (McAllister et al. 2002). We did not record sexes century (Lewis 2002; McAllister et al. 2002, because this milliped is the only representative 2005, 2013; McAllister and Shelley 2003a, of the Platydesmida in the state that can be 2003b, 2005, 2008, 2010; Shear 2003; Shelley et authentically identified with either sex and/or al. 2005a, 2005b, 2006; McAllister and Robison with juveniles. 2011; Lewis and Slay 2012; Shelley and Snyder 2012). However, there are still gaps in the This milliped had been previously reported distribution of many species. Here, we continue from only two counties, Le Flore and McCurtain to help fill some of those gaps with a noteworthy (Appendix) in the southeastern corner of the county record of an uncommon milliped of state on the Ouachita uplift. It is typically found the state. Additionally, we provide an updated under decaying hardwood logs or under the bark distribution for this species in Oklahoma and of those logs but as yet not under pine logs or surrounding states. bark. The current location (Flint) is important as it is on the Ozark Plateau of Oklahoma, which On 1 April 2016, MBC collected two millipeds extends northward and ends in southeastern from a cave/spring outflow site off county road Kansas in the vicinity of Galena, Cherokee 660 at Flint, Delaware County (36° 12’ 27.83”N, County (see Shelley et al.