The Unresolved Problem of Rohingya Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Statelessness in Myanmar

Statelessness in Myanmar Country Position Paper May 2019 Country Position Paper: Statelessness in Myanmar CONTENTS Summary of main issues ..................................................................................................................... 3 Relevant population data ................................................................................................................... 4 Rohingya population data .................................................................................................................. 4 Myanmar’s Citizenship law ................................................................................................................. 5 Racial Discrimination ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arbitrary deprivation of nationality ....................................................................................................... 7 The revocation of citizenship.................................................................................................................. 7 Failure to prevent childhood statelessness.......................................................................................... 7 Lack of naturalisation provisions ........................................................................................................... 8 Civil registration and documentation practices .............................................................................. 8 Lack of Access and Barriers -

Crimes Against Humanity the Case of the Rohingya People in Burma

Crimes Against Humanity The Case of the Rohingya People in Burma Prepared By: Aydin Habibollahi Hollie McLean Yalcin Diker INAF – 5439 Report Presentation Ethnic Distribution Burmese 68% Shan 9% Karen 7% Rakhine 4% Chinese 3% IdiIndian 2% Mon 2% Other 5% Relig ious Dis tr ibu tion Buddhism 89% Islam & Christianity Demography Burmese government has increased the prominence of the Bu ddhis t relig ion to the de tr imen t of other religions. Rohingya Organization • ~1% of national population • ~4% of Arakan population • ~45% of Muslim population Rohingya Organization • AkArakan RRhiohingya NNiational Organi zati on (ARNO) • Domestically not represented Cause of the Conflict • Persecution and the deliberate targggeting of the Rohdhl18hingya started in the late 18th century whhhen the Burmese occupation forced large populations of both the Rohingya Muslims and the Arakanese Buddhists to flee the Ara kan stttate. • The Takhine Party, a predominant anti-colonial faction, began to provoke the Arakanese Buddhists agains t the Ro hingya Mus lims convinc ing the Buddhists that the Islamic culture was an existential threat to their people. • The seed of ha tre d be tween the two sides was plan te d by the Takhine Party and the repression began immediately in 1938 when the Takhine Party took control of the newly independent state. Current Status • JJ,une and October 2012, sectarian violence between the Rohingya Muslims and the Arakanese Buddhist killed almost 200 people, destroyed close to 10,000 homes and displaced 127, 000. A further 25, 000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Sir Lanka, and Thailand. • Tensions are still high between Rohingya Muslims and Arakanese Buddhists and human rights violations persitist. -

Burma (Myanmar) Rohingya Refugee Wellness Country Guide

Overview and Context e a d The history of the Rohingya people in Burma (Myanmar) dates i y back to the 15th century. Despite this history in Burma, the u g Rohingya are not viewed as legal citizens or recognized as one of G the 135 official ethnic groups within Burma. The Rohingya primarily n live in the Rakhine (Arakan) state, the poorest state in Burma. In y r i 1982, the Burmese government rescinded the Rohingya’s t citizenship status, severely limiting their ability to vote, travel, or own h n property. Although democratic elections were held in 2012, u Rohingya have faced increased violence perpetrated by the o o government since 2012, including mass rape, torture, and killings. C R Rohingya identity cards were canceled in 2015, further limiting movement, and rendering the Rohingya essentially stateless. s ) s r As a result of this ongoing discrimination, approximately 120,000 Rohingya have been internally displaced, e n 1,000,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, and 150,000 have fled to Malaysia. The Rohingya are referred to a l by some as the “most persecuted group in the world.” Many believe the atrocities committed against this group l are tantamount to genocide. e m W n Country Info Mental Health Profile e a Population e Research suggests Rohingyan refugees who have g y fled to refugee camps experience high levels of Approximately 1 million live u stress associated with the restrictions of camp life, f in Burma (Myanmar) M such as lack of freedom of movement, safety e concerns, and food scarcity. -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT for MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 –

Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 – Title: Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar Document reference FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN code: Approval body: FSC International Center: Performance and Standards Unit Date of approval: 27 August 2018 Contact for comments: FSC International Center - Performance and Standards Unit - Adenauerallee 134 53113 Bonn, Germany +49-(0)228-36766-0 +49-(0)228-36766-30 [email protected] © 2018 Forest Stewardship Council, A.C. All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the publisher’s copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, recording taping, or information retrieval systems) without the written permission of the publisher. Printed copies of this document are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy on the FSC website (ic.fsc.org) to ensure you are referring to the latest version. The Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC) is an independent, not for profit, non- government organization established to support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests. FSC’s vision is that the world’s forests meet the social, ecological, and economic rights and needs of the present generation without compromising those of future generations. FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 2 of 178 – Contents Risk assessments that have been finalized for Myanmar .......................................... 4 Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for Myanmar ................................... -

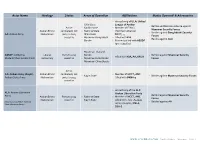

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 438 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Tamara Decaluwe, Terence Boley, Thomas Van OUR READERS Loock, Tim Elliott, Ylwa Alwarsdotter Many thanks to the travellers who used the last edition and wrote to us with help- ful hints, useful advice and interesting WRITER THANKS anecdotes: Alex Wharton, Amy Nguyen, Andrew Selth, Simon Richmond Angela Tucker, Anita Kuiper, Annabel Dunn, An- Many thanks to my fellow authors and the fol- nette Lüthi, Anthony Lee, Bernard Keller, Carina lowing people in Yangon: William Myatwunna, Hall, Christina Pefani, Christoph Knop, Chris- Thant Myint-U, Edwin Briels, Jessica Mudditt, toph Mayer, Claudia van Harten, Claudio Strep- Jaiden Coonan, Tim Aye-Hardy, Ben White, parava, Dalibor Mahel, Damian Gruber, David Myo Aung, Marcus Allender, Jochen Meissner, Jacob, Don Stringman, Elisabeth Schwab, Khin Maung Htwe, Vicky Bowman, Don Wright, Elisabetta Bernardini, Erik Dreyer, Florian James Hayton, Jeremiah Whyte and Jon Boos, Gabriella Wortmann, Garth Riddell, Gerd Keesecker. -

How Narratives of Rohingya Refugees Shifted in Bangladesh Media, 2017-2019

University of Nevada, Reno Good Rohingyas, Bad Rohingyas: How Narratives of Rohingya Refugees Shifted in Bangladesh Media, 2017-2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by Mushfique Wadud Dr. Benjamin J. Birkinbine/Advisor August, 2020 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by entitled be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Advisor Committee Member Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean Graduate School i Abstract This study investigates how Rohingya refugees were framed in Bangladeshi media outlets from August 2017 to December 2019. Rohingyas are ethnic and religious minorities in Myanmar’s Rakhine state who have faced persecution since after the post second world war. The majority of Rohingyas fled to neighboring Bangladesh after a massive crackdown in Rakhine state in August, 2017. A total of 914,998 Rohingyas are now residing in refugee camps in Bangladesh (as of September 30, 2019). The current study uses framing theory and a qualitative content analysis of 448 news stories and opinion pieces of six daily newspapers and two online news portals. This study examines the dominant frames used by Bangladeshi news outlets to describe Rohingya refugees. The study then goes on to investigate how those frames shifted over time from August 2017 to December 2019. It also investigates whether framings vary based on character of the news outlets and their ideologies. The findings suggest that the frames varied over time, and online news outlets were more hostile towards refugees than mainstream newspapers. -

The Rohingya Response in Bangladesh and the Global Compact on Refugees Lessons, Challenges and Opportunities

HPG Working Paper The Rohingya response in Bangladesh and the Global Compact on Refugees Lessons, challenges and opportunities Karen Hargrave, Kerrie Holloway, Veronique Barbelet and M. Abu Eusuf April 2020 About the authors Karen Hargrave is Humanitarian Policy and Advocacy Adviser at the British Red Cross. Dr Kerrie Holloway is Senior Research Officer with the Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG) at ODI. Dr Veronique Barbelet is Senior Research Fellow with HPG at ODI. Dr M. Abu Eusuf is Professor and Former Chairman of the Department of Development Studies and Director with the Centre on Budget and Policy at the University of Dhaka, and Executive Director of the Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID). Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those individuals who kindly gave up their time for interviews. The authors are grateful for all the comments and inputs provided by external peer reviewers as well as colleagues at the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society, the American Red Cross, the International Federation of the Red Cross, the British Red Cross and HPG at ODI. Thank you to Sarah Cahoon for her management of the project. This report could not have been published without the expert support of editor Katie Forsythe and publication manager Hannah Bass. In partnership with In association with Supported by players of Readers are encouraged to reproduce material for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website.